The majority of Cuba’s young people — those who left and those who stayed — are no longer interested in mass rallies

![]() 14ymedio, Yunior García Aguilera, 13 April 2024, Madrid — Those open mass rallies in which Hassan Pérez Casabona stunned the crowds with his rapid-fire barrage of words are still fresh in the minds of many Cubans. At the end of each Saturday, the streets were a sea of trampled flags, empty plastic bottles and chewed-up chicken bones. People went home not understanding why these events were called “open.” In reality, they were a closed circuit in which every speaker just repeated what the previous one had said. A highly rehearsed monologue of multiple voices, it was the culmination of the Castro liturgy. Almost all the speakers whom Fidel Castro had thrust into stardom later faded under the brightness of the four stars on his little brother Raúl’s shoulder straps.

14ymedio, Yunior García Aguilera, 13 April 2024, Madrid — Those open mass rallies in which Hassan Pérez Casabona stunned the crowds with his rapid-fire barrage of words are still fresh in the minds of many Cubans. At the end of each Saturday, the streets were a sea of trampled flags, empty plastic bottles and chewed-up chicken bones. People went home not understanding why these events were called “open.” In reality, they were a closed circuit in which every speaker just repeated what the previous one had said. A highly rehearsed monologue of multiple voices, it was the culmination of the Castro liturgy. Almost all the speakers whom Fidel Castro had thrust into stardom later faded under the brightness of the four stars on his little brother Raúl’s shoulder straps.

The vast majority fell into disgrace. For example, Otto Ribero, the former first secretary of the Young Communist League and vice president of the Council of Ministers went into a drunken, downward spiral before going through a public catharsis on Facebook. He proudly confessed on that platform to having personally signed the regulation preventing Cubans from leaving the island even though his children were already living overseas. Never before has the expression “other people’s shame” made more sense. That poor devil was full of praise for his executioners from the Ministry of the Interior, thanking them for every slap in the face, every kick in the groin.

Hassan Pérez Casabona managed to survive by sneaking away, lowering his profile by retreating into the basement

Hassan Pérez Casabona managed to survive by sneaking away, lowering his profile by retreating into the basement. He emerged two weeks ago in an appearance on the Venezuelan state television network Telesur, spouting the same rhetoric as before but now breathing like someone with chronic continue reading

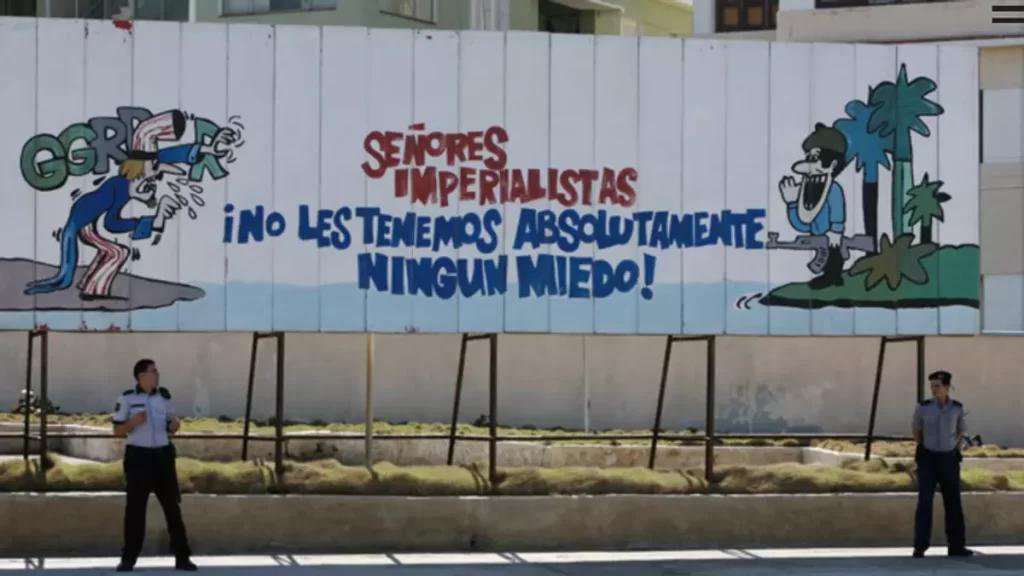

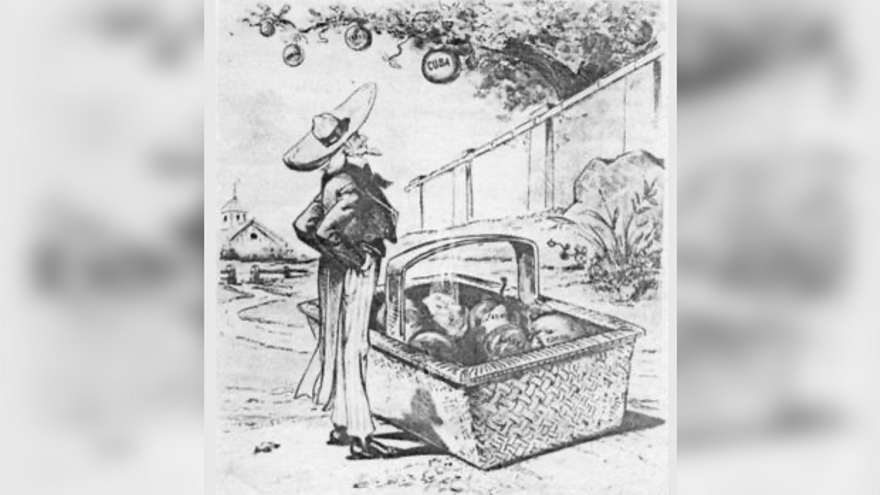

Over a five-year period, dozens of these rallies were held, wasting the flow of oil that Hugo Chávez had given us. The last one took place on March 12, 2005, in Caimanera, thus concluding the cycle of a larger project: the Battle of Ideas. The emperor’s last act of madness worked like a temporary suppository. For five years the country had been entertained by demands for the return of a shipwrecked boy and the release of five would-be spies. From time to time Díaz-Canel tries to resurrect this ethos but, with no causes of his own, he has to inspire people by pretending to be Palestinian.

The majority of Cuba’s young people — those who left and those who stayed — are no longer interested in mass rallies. However, some have enthusiastically signed up for a new crusade: the Cultural Battle. Now the rhetoric is coming from the other end of the spectrum. Dozens of Cuban social media users spout paleo-conservative slogans with religious zeal. Some have become shepherds — instructing their flocks in the theories of some Austrian economist — with the same effusiveness with which others previously indoctrinated us with Marxist ideas. New mirror-images of Otto and Hassan have emerged, trying to impose absolute truths, worshiping new commanders-in-chief, or shouting “we don’t want them, we don’t need them” at those who do not think like them.

New mirror-images of Otto and Hassan have emerged, trying to impose absolute truths

First of all, I consider the ideology of these Cubans to be as valid as that of anyone else. I also believe they have every right in the world to passionately defend it with arguments, to choose the leaders they prefer, to share beliefs as a group, to participate in whatever public discussion they desire and even to win out in the end. However, the alarm bells go off when democracy stops making sense for them, when they reject pluralism or when they try to present themselves as the only possible option in a future Cuba. We have suffered from authoritarian thinking for too long. The best antidote to decades of dictatorship would be a diversity of opinions, a search for consensus between opposing views, and political alternatives.

Believing that we are right and everyone else is wrong is as human as blushing. But killing the tyrant we carry within us is essential to overcoming this long totalitarian period and building something truly different. Nothing is more boring than a meeting between those who think the same way and share the same opinions. Nothing stagnates a country more than the imposition of a single doctrine. That most beautiful word, freedom, should not be limited to discussions about economic freedom. It has to also be about freedom of mind and body.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.