Literary spaces

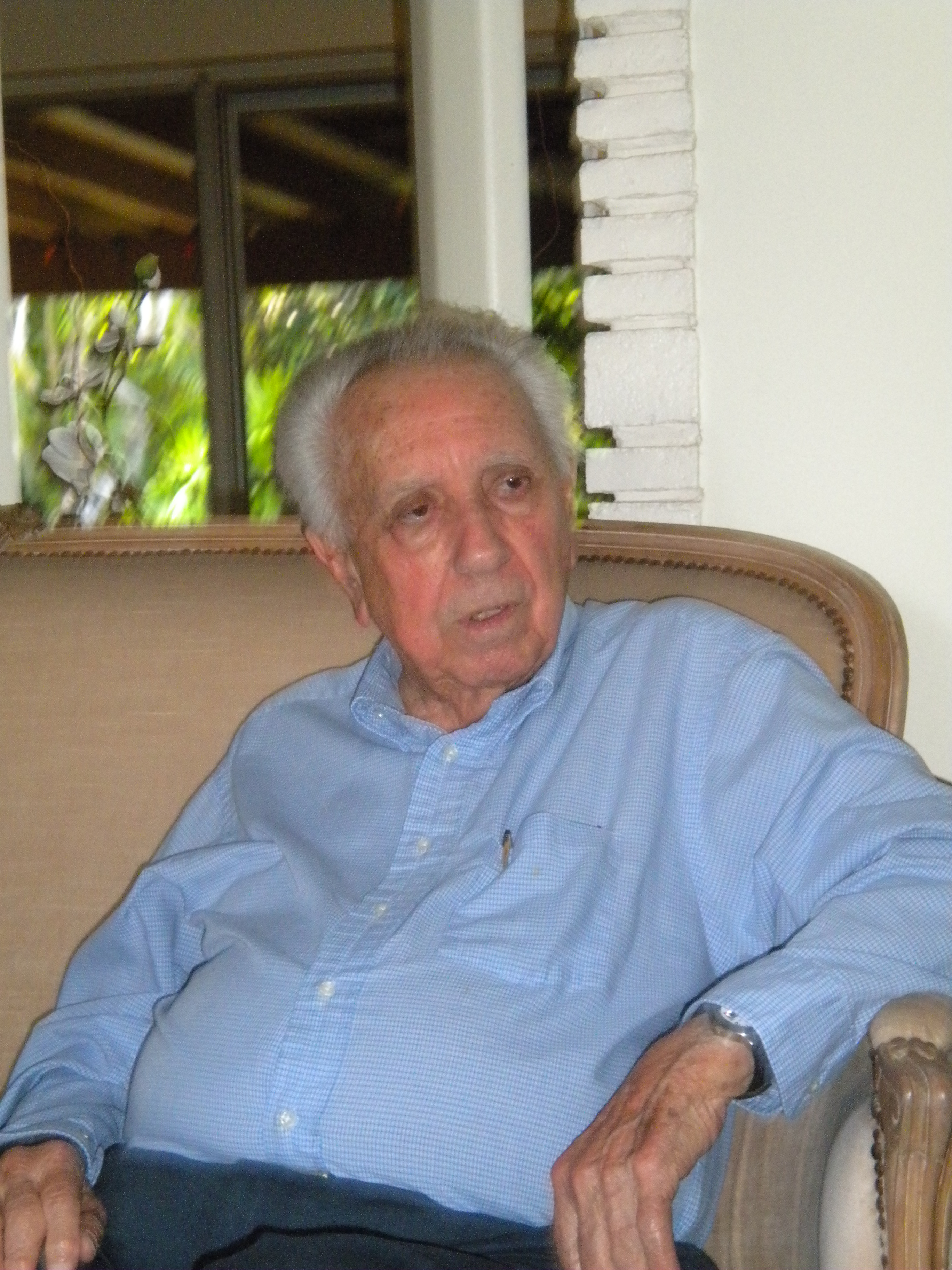

There are five moments in your literary career that I want you to talk about, trying to salvage the most important details, those details of each success that would mold you into being the writer you are now, or those other moments that made you open your eyes to the harsh reality that you are experiencing today.

A. Honorable mention for the Juan Rolfo International Short Story Prize, in 1989

A surprise. I considered myself, more than now, an experimental writer, not an accomplished one. I only entered the contest hoping to receive an opinion from a foreign jury. I wanted to know if my writing worked outside Cuba. If it would be interesting or boring, with a regional theme. It was the first time that established writers heard my name. In a certain way, I put myself on the map of the “newbies”.

B. The two times they took away your Casa de las Americas award.

Very sad, not just for me but also for the position they put the jurors in. The book’s subject was the war in Angola, where we remained for 15 years and where many lives were lost by Cubans who never understood why the hell we were there. The book was not an epic, as this war was usually treated. I was only interested in the human side, the men who were immersed in a foreign war.

I’ll never forget the face of Abilio Estevez giving me the unexplainable dissertation about the book, and that you later would write that the worst book of all won the Casa de las Americas prize that year. Abilio said that in the hotel when they were reading the works, they paged him on the PA system to come to the room. When he arrived, Security was waiting, and they told him that no one wanted to give this book an award.

They did the same thing with the Argentinian juror, Luisa Valenzuela, who later wanted to take me with her to her country because I was the same age as her daughter, and with this fact I understood how difficult it would be for me to rise in the literary world under the Regime. This was in 1992. Since then I’ve been reluctant to leave the country, and I told her I was grateful, but only God knew why I had been born here and that I wanted to stay. She never agreed, I imagine, and when the Alejo Carpentier prize was launched, I did everything possible so she could get an invitation to Cuba and be present.

Later in 1994 something similar happened, but this time State Security was more careful and tried, without success, to infiltrate the jurors. But the books survived the Tyranny and its Totalitarian Leaders. Censorship has never been able to stifle art. Once a writer told me that my book was unfair to those who had been in this war. And when I told Heras those words he told me that books weren’t fair or unfair, they were only good or bad, speaking from a literary point of view.

C. The 1995 UNEAC short story prize for Dream of a Summer Day and the publication of the book, with the censorship included, in 1998

Books catch on when one more person needs them, they are like life jackets. And this award finally gave me the possibility to be a published writer, because they knew me in the cultural milieu, but I didn’t have a book, which is definitely the calling card of a writer. It was also the genre of the short story, which is the most coveted genre in Cuba, above all for our generation. But the book was the same one that had been censored, anticipating that State Security would come back to spoil the award for me.

I changed the title (Dream of a Summer Day) and it passed through the filters and won. When they saw this book was going to be published, and that it talked about the human part, man immersed in that war, the contradictions, then the book started an emotional discussion. The book floored them. It went from one bureau to another. Occasionally they called me in to talk about my negativity in publishing it before they were able to edit it. And again I assumed the silence of Gandhi, but with the variant that I didn’t want a political scandal, what I wanted was literary. To be part of cultural news.

They even decided to call me to negotiate. They spoke to me openly, there were several stories that couldn’t see public light, above all the story The Forgotten, “It wouldn’t be published in 25 years”, the functionary told me (I managed to publish it in 2001 in the book The Children Nobody Wanted, which won the Alejo Carpentier prize).

As I told you before, I urgently needed to present a book, but I hurt myself with this book, because I accepted that it would be published without those stories. This was a betrayal, the worst of all, a betrayal of myself. But the need to publish was joined with another unexpected one: A woman was expecting my child and I didn’t have a place to live. They offered me an apartment. I thought about it a bit. I immediately saw the possibility of giving the woman and my child some stability in the next few months.

I also thought that any publisher would have the right to read the book and determine what to publish, and that the functionary was finally giving me the possibility of having a book published. And in exchange for the unpublished stories they were giving me an apartment. I felt like I was bargaining in a market in Baghdad, and at any rate, man is and always will be “a part of his circumstances”. I accepted. The book came out in the 1998 Book Fair, with a dark cover. They did it on purpose, so it looked less like a book and more like a box of detergent. Thus I achieved my goal of presenting myself to readers, and incidentally my first child was born in a dignified place.

D. The 2001 Alejo Carpentier Prize for The Children Nobody Wanted

This book has all my censored stories. That’s why I gave it this title. Furthermore, the story with the same name is included, and I felt that those scorned, censored stories were like the young people who escaped on rafts from the island. I found a similarity in both cases.

The jury’s vote was divided, of course. They all knew what they were risking by giving me the prize. The two votes in my favor were from Arzola (he had won the prize the previous year), and what decided him was a telephone call from the office of the then-President of the Cuban Book Institute, the “Taliban” Iroel Sanchez, who, as you know, is a new version of that person named Pavon who harmed Cuban culture so much.

They told me that Iroel opened his eyes as if praying to his gods, I imagined Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Marx and Engels, and his adored Fidel Castro, for whom he felt an almost homosexual love.

But coming back to the jury, Arzola left Cuba a little time after the award, but the other juror was none other than Eduardo Heras Leon. And certainly I entered the competition even when I didn’t know who the jurors were going to be, because if I had known he was there I wouldn’t have entered since that added fuel to rumors about our friendship later. And Heras, at least until 2009 when he lost his path, hadn’t been invited to any other competition than the one convened by the Book Institute.

That was the punishment that Iroel imposed on him, who told me that the Association of Cuban Combatants had complained in a letter, demanding an explanation for the publication of the book, and on a more personal plane, he commented that his buddies who were in Angola with him criticized him for publishing such a ruthless vision of war under his position as President of the Book Institute.

I asked him if the book told lies. “That’s the problem,” he answered. “We know it was like that and worse. But Angel is the enemy who takes advantage of our weaknesses to attack us. We can’t give him the pretext.”

Later it was funny. They took me to the Book Fair in Guadalajara, as every year they did with the Carpentier award winners. And they coordinated various presentations in universities, and in charge of this were some Mexicans from a Committee of Solidarity with Cuba. When the students asked about human rights in Cuba, my companions answered trying to discredit the dissident groups and calling them”factions”, a word coined by Fidel Castro, which everyone repeated later. That bothered me so much I took the word and said that 100, 50, 10, five or one, we had the same rights to think and choose as the other millions of Cubans. And the students and cluster of professors stood up and applauded me.

Upon my return, the organizers spoke with Iroel so they could exchange me for another writer, because I wasn’t giving them the right result. That made me laugh. And they exchanged me, of course, in the way that is typical of socialism. No one says anything to you, but everyone shuns you as if you had the plague. And later I saw several times that people I knew on the bus wouldn’t greet me. Of course, I took this on myself and didn’t mind.

In the official presentation of the book at the fair, all the functionaries of Cuba were there. At my side was Jaime Sarusky, who that year had won in the novel genre. And while I was talking, I saw how his hands were sweating. I’ve never seen anyone sweat so much. Drops were falling on the paper he later would hold to read and I started to worry that it would get smudged.

I was saying, in answer to some question from the public, that I wasn’t trying to bother anyone, but yes, being honest, above all with myself, that I identified with that sector of young Cubans who didn’t find any common ground between the Revolution and our generation. That the Revolution was something from the past with which we didn’t feel a connection. And I finished by saying that the majority of young people I knew were of the same opinion.

The functionaries remained stoic. They put up with it, but many years later, Iroel reminded me of it as a disagreeable moment in his life. For my acts of honesty I always was punished. In Manzanillo I knew that they had received calls and emails from the Book Institute, from the writer Fernando Leon Jacomino, who at that time was Vice President, criticizing them for inviting me and suggesting that they substitute the writer Rogelio Riveron for me.

On another occasion they called me to make me President of the Wichy Nogueras prize, and later they didn’t advise me of the countermand. And when I arrived at the Capitolio, to know the results, they told me I no longer was part of the jury. Or what happened in the last Book Fair in which I participated: I was in the Moron Hotel and Security asked to have me removed from my room. That night I slept at the home of our taxi driver.

Now I am a phantom writer.

E. The 2006 Casa de las Americas prize for Blessed are Those Who Mourn, the hardest and most critical of your books

It’s because the book touches the knottiest fiber of human beings: prison, the prisoner immersed in the most profoundly undesirable condition for survival. I could finally use all those experiences that I lived through in La Cabana. Some friends begged me, I think with the best intention, to not do it. They didn’t want to see me harmed, banished, as they had been in the Five-Year Gray Period, I shouldn’t write it since it wouldn’t be published. And the book contains only 20 percent of that repulsive reality. Now I’m writing a novel that frightens me because I’m releasing what I’ve kept inside. I want to be empty, to not return to this subject. To get it out. Because when I write, I hurt, I rip myself up in a way that makes me feel that everything is happening again.

The book, in one of those ironies in life, was presented at the Book Fair in the Cabana. It took place in one of those cell blocks in which I was incarcerated. While the others were expressing their impression of the book, I in my imagination was walking with the prisoners from one side to the other. I had gone back in time, and the people interested in Culture were substitutes for those who had struggled to survive physically and morally, who served as characters, so that my suffering and anguish would not be in vain. That was my way of paying homage to them, offering them my gratitude in spite of their being the same people who enthusiastically had rejected the gesture by not being part of that reality that so marked us.

For having shared the experience, the book is dedicated to Jose Marti, who really is the perennial convict blessed with Cuban goodness.

Translated by Regina Anavy, AnonyGY, Rafael Gomez, and William Fitzhugh

Interview December 2011

Posted to Angel’s blog: 5 April 2012