By Carlos Manuel Álvarez, published in Univision News, 19 May 2016 Published in Malaletra, a Blog Made in Cuba, Regina Coyula, 11 July 2016

He looks like a god but is a heretic. He seems carved in stone, but is a nervous wreck. He looks like the first among men, but is just the last survivor.

Marina Tsvetaeva, the great Russian poet, said of Rilke: “He is not a symbol of our time, he is its counterweight. Wars, massacres, flesh lacerated in battles, and Rilke. Thanks to Rilke, our time will be forgiven.”

At eighty-two, Rafael Alcides is Cuba’s counterweight. Political courtesans, a nation eaten away by its own skepticism and cowardice, lives wasted in a useless march to nowhere, permeated by resentment and fear, and Alcides. Thanks to Alcides our country will be forgiven.

At age 82, in sacred communion with the world, equally reconciled with defeat and with light, Alcides is all he seems and is also all he is. A poet. He is someone who once wrote, “When a funeral procession of two lonely cars/ goes by and nobody cares, I quiver, I shudder, / I throb; I am afraid of being a man.”

***

He lives in a garage turned into an apartment — a cave, almost — on the corner of a quiet street in Havana’s Nuevo Vedado neighborhood. It is not the crumbling house of a tortured genius. It is not the lavish home of an acclaimed author. It is not the suffocating house of a bureaucrat. It is not the empty house of a suicide. It is a quintessential example of “mature homes, / where the act does not allow itself to be replaced by the word.”

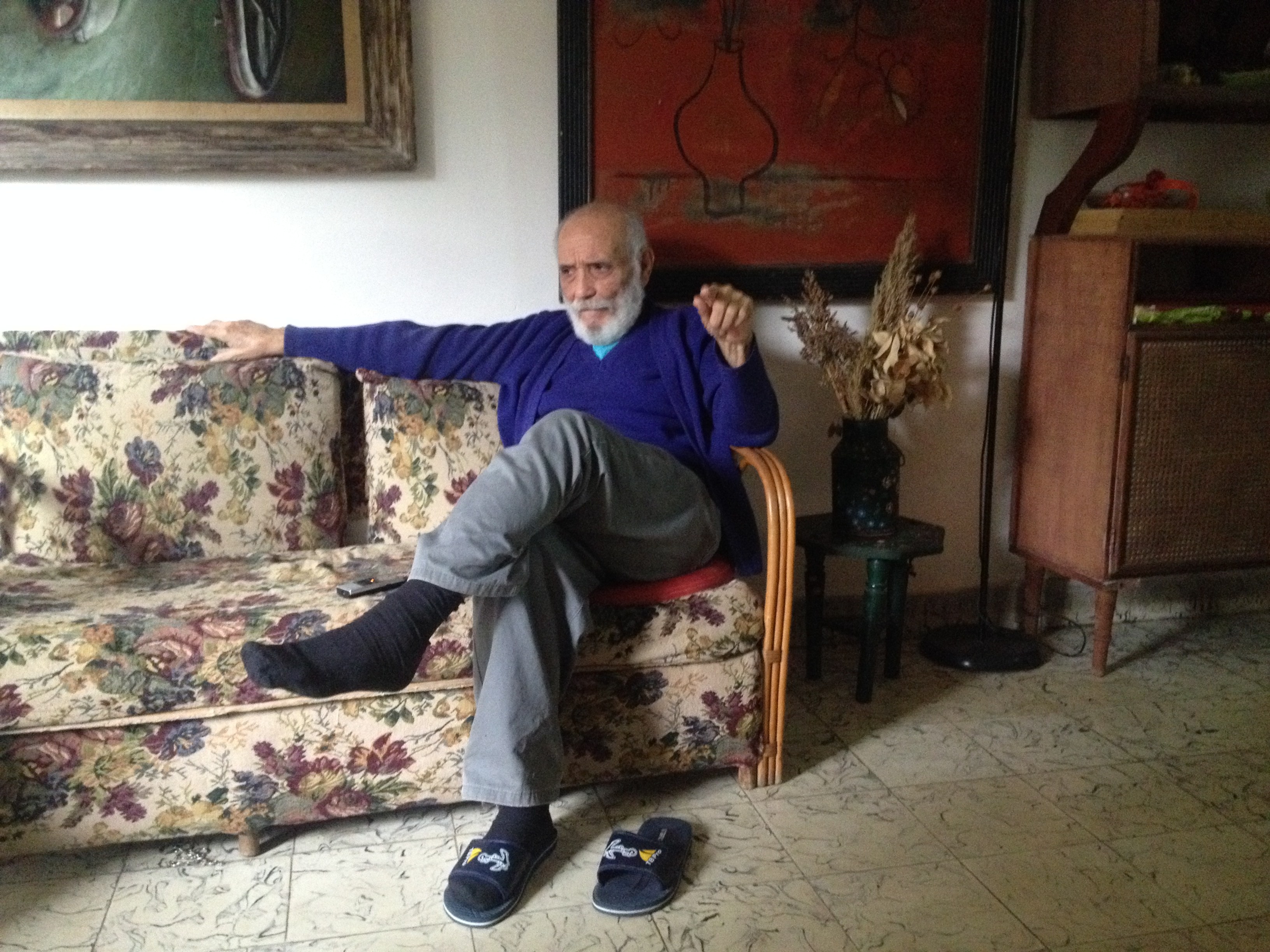

The volitional force that is Rafael Alcides inhabits an ideogram. The narrow sofa, almost at floor level; the cushions with patterns of tremulous flowers; the still life painted on the ceramic vases; the polished wood of armchairs; the wicker furniture; the wax candles; the sober paintings, with motifs ranging from the ordinary to the lugubrious; the dim lighting; the pusillanimous cold of Havana winters; the afternoon’s plasticity; the vague noise of apparently uninhabited spaces; and the inconstant barking of a lanky dog, with variegated eyes and floppy ears.

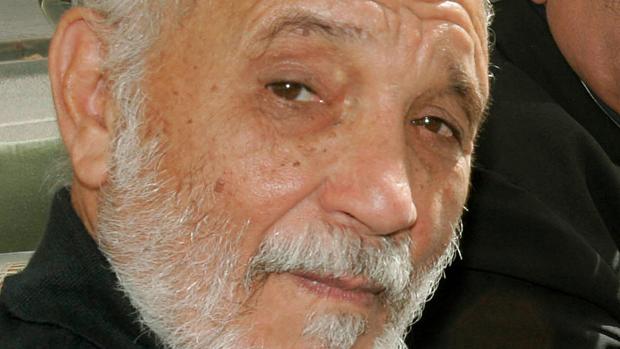

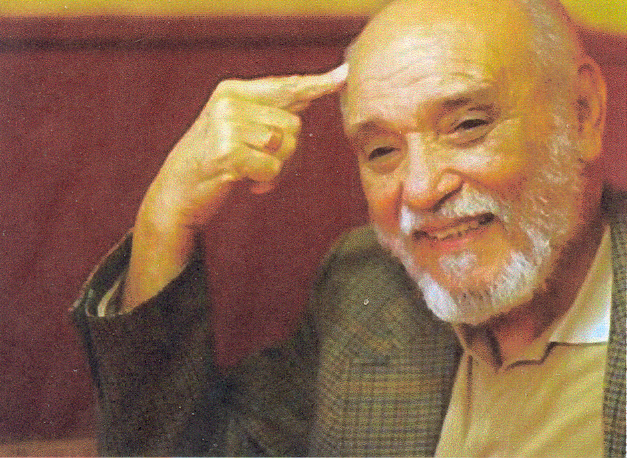

Regina Coyula, his wife who is 23 years his junior, brews coffee in the kitchen, and from the back of the apartment, enveloped in this conversational aroma, Alcides emerges. A man who, in order to describe him, calls forth the exclamation that today — except when aimed at him — would sound ridiculous for anything else: “Oh!”

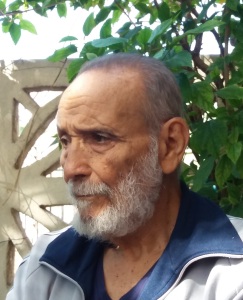

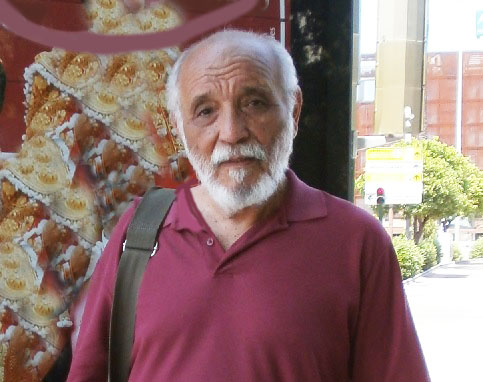

He sports grey heavy trousers, a navy blue sweatshirt, black socks and slippers. The white and generous beard, his elegant baldness, his coppery country skin, wrinkled forehead, and in the depths of his face, howling, the feverish black eyes.

He recites the verses of Rubén Darío:

“Margarita, the sea is beautiful / and the wind / brings the subtle essence of orange blossom!”

The grave and tremendous voice, combined with his scintillating gestures, produces a strange fascination.

“I feel / in my soul a skylark singing; / your accent…”

The hands seem to initiate a subtle dance, led by the vertiginous rhythm of the words. Long, aged fingers trace the words as if his mechanisms of expression were activated all at once and nothing within Alcides were disconnected. If he is going to say something, he says it with his whole being.

“Margarita, I am going to tell you / a story.”

His ears are filled with water, he can’t hear himself, and a few meters away everything is in shadows. Alcides has spent the last two months in bed, except on the days when he goes to the hospital so the doctors can check on him. Only thus he has reconnected with a city with which he wanted nothing further to do, consciously isolating himself from the final stages of its destruction.

“For more than 20 years now, Alcides’ life can be summed up in a linear kilometer. From the apartment to the farmers’ market and from the apartment to the bodega [ration store],” says Regina.

Last November he had surgery for colon cancer; the doctors found it had metastasized and they performed a colostomy. But he still hasn’t decided whether or not to undergo chemotherapy. It seems he would rather spend his last months peacefully, regardless of how many may be left, rather than drawing out the process amid vomiting and nausea.

What is striking about all this, however, is his renewed capacity to celebrate concrete details that others might consider minutiae. This is something that no cancer — whether it is political power or the actual disease – has been able to take away from him. Today, 19 January 2016, Alcides just finished reading with delight the recent criticism of his work by one of his fervent readers.

“I’m going to be a beautiful corpse,” he says, “remembered with love.”

But he is not dead yet. He is Cuba’s greatest living poet and very likely the most honest, the most unjustly silenced, the one who has paid the highest price for his nobility, and the one who has not been subverted by fashionable trends nor bought by politicians’ petty cash. continue reading

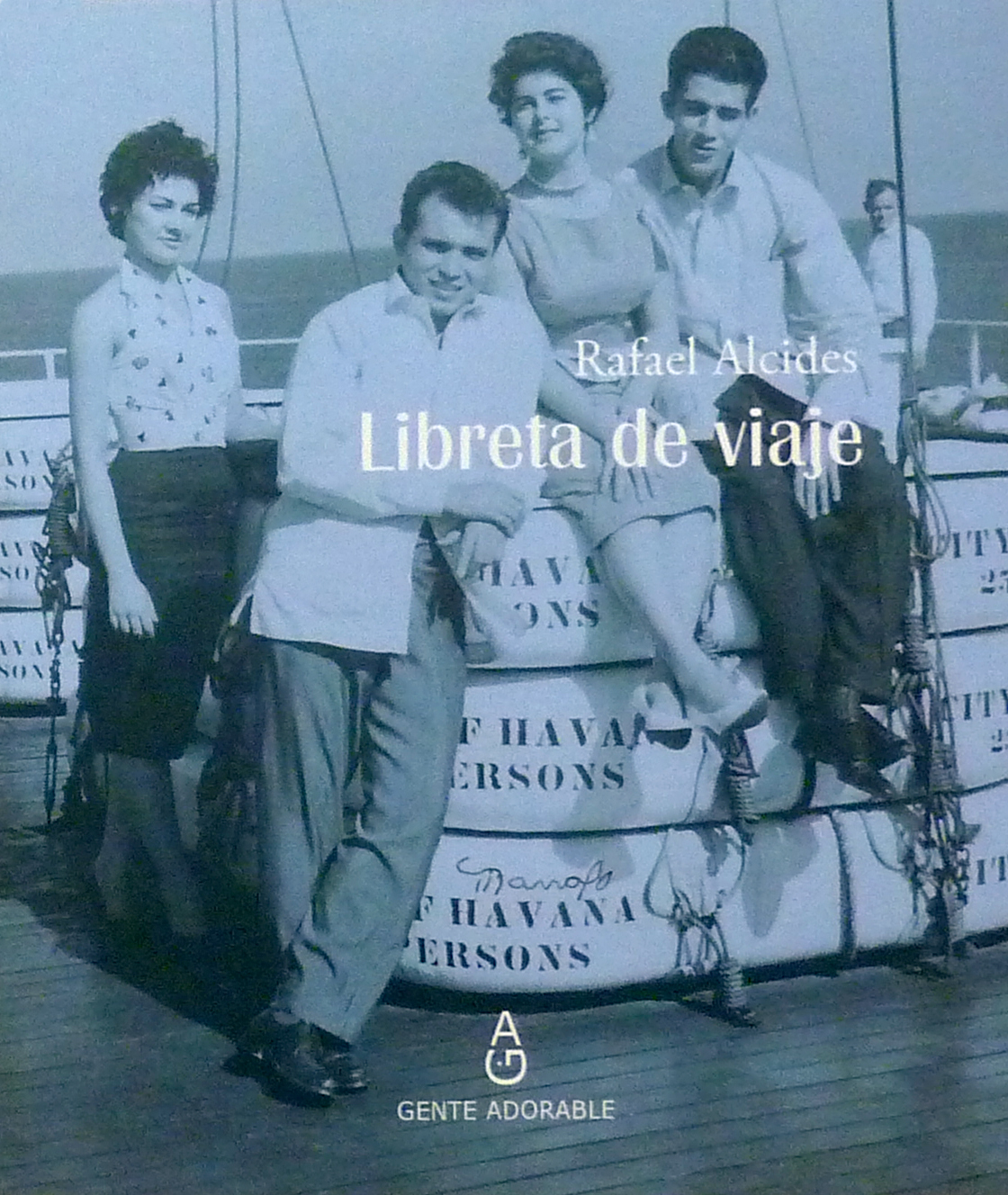

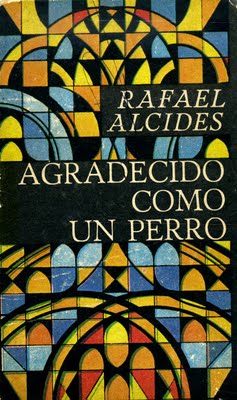

Intermittently published, he has received some quite unusual awards. In Cuban prisons, in the Eighties, the inmates exchanged cigarettes for his book, Agradecido como un perro [“Grateful as a dog”]. The only things a rafter would take with him across the Florida Straits were Alcides’s books wrapped in plastic so that the sea would not destroy them. Young people from the provinces would show up at his house after reading some book of his at some second-hand bookstore.

Alcides is not a poster boy for exile. He is not a plaintiff from the Five Grey Years. He did not become cynical, coarse, sarcastic, cautious, or violent, nor even less did he ever cave in. For some inexplicable reason, he cares less about his personal luck and more about the death of his country.

“If I lose my book, after many years of writing it, I am the one who loses. That is my own personal loss. But this is the loss of the people and it is a sacred thing, a tragedy: We have a patchwork of capitalism and socialism that means nothing. Look around for a damned vegetable. You won’t find it. Look at the prices. Is it the blockade’s [embargo’s] fault? Are you fucking kidding? You can’t be serious. What, the produce comes from London? The sweet potatoes come from Paris?

“No. Life goes on and it’s like a chess game. Each move changes the game. You cannot be rigid. This continues because Fidel and Raúl are in a duel with the United States. A shameless and mendacious duel; because Raúl says, ‘We can hold on for another 50 years’… yes, of course, you can hold on. But the people can’t hold on anymore. In no way am I proud of this situation. I feel like the worker who helped build the prison. I am one of those workers. But, if I reincarnated and were given the same circumstances, I would again join in that struggle and do everything that I did. I would sign up for that campaign. We thought we were going somewhere, even though it turned out that we didn’t arrive anywhere.”

— What about your literature?

“I don’t talk about my literature. My history is very simple. In the end, I have been an author of drafts. I have three or four meter-length of novels in my closet, and that’s where they’ll stay. Thirty years ago, when I moved to this house, I burned another meter and a half.”

— Doesn’t this trouble you?

“There was a time when it did trouble me, because it’s what I lived for and gave my life to. But later, you have much less anxiety. Why? Because there have been bigger losses. The biggest loss was losing the Revolution itself; it was the dream of many people like me. There was an opportunity, the opportunity existed, but that is a train that will not pass again.”

***

Previously, in an interview with the critic and writer Efraín Rodríguez Santana (Cuba Encuentro magazine, No. 36, spring 2005), Alcides had acknowledged that he burned his novels to pay off the mortgage on a future that was weighed down by so much draft material that he would never be able to finalize. In this sense, it can be said that the Revolution itself is the unfinished novel, allegedly complete, never to be finished, that its authors insist on continuing to write at the wrong time. Politicians are politicians precisely because the generosity of true poets is unknown to them.

***

“In Cuba, a Revolution was needed. What happens is that the Revolution soon ceased to be Revolution and became something else. Fidel began to do whatever he wanted, to lead wars around the world in which, on the other hand, he did not participate — unlike Alexander, Hannibal, and Napoleon, who did participate. Not even his children were there.”

— If we had to venture a year in which the Revolution ceases to be “Revolution”…

“Starting at the moment the new legal body is created. When it was established that blacks and whites were equal, that everyone had the same rights, and that the state was controlling the means of production…at that moment is when the Revolution ends. What takes its place is the natural contract between man and state and man and society, the social contract of all times, where the citizen produces, pays taxes, the state collects, distributes what it collects, builds schools, pays the salaries of officials, the army, the salary of Fidel and Raúl. That state is responsible for giving you a scholarship if you perform well, ensuring that you have a free education — which is essential — and hospitals, and doctors.

“The Revolution ended in 1965 or 66. But — what’s wrong with this picture? It’s that Fidel is very cunning, very intelligent, he is a genius, no doubt about it — he is sinister, and he retained the name, Revolución, that abstract entity. Why? Because that way you owe things to the Revolution. But since the Revolution has no face, it is not a figure, you need to identify it with someone. Your father was a garbage collector and you became a doctor or lawyer thanks to the Revolution, that is, thanks to Fidel Castro. You owe everything to Fidel Castro.

“No! No! Fidel Castro owes everything to you, everything he is, the glory and power he has, has been given to him by the people, by me as part of the people. I pay him the salary to manage and direct, I have trusted him. That story of ‘At your orders, Commander in Chief’… No, sir! The sovereign is me, it is not you, you must take off your hat to the people, who are the true sovereign, the one who puts the hat on your head and the one who can take it away. This [would be], of course, things rightly understood in a rule of law. Here, you can’t take away fuck. He’s the one who can take away from you, he can take your life.”

–Did you ever admire him?

“Yes, of course, I followed him, he was the chief.”

— Did you have affection for him?

“Affection is a strange word. Affection is one thing. Love is another. Respect, admire, feel a part of. Rather, I felt a part of it all. Also, you have to think of yourself as a big octopus, because you love people for many reasons. So, you’re a leader, you’re a boss, you represent an idea, and there are lots of friends of yours who have been friends of mine and have died — that is, we are all part of an ideal. Already, once I know you, we are united by all those affections of people who have loved you and whom you have loved, or supposedly have loved. We are part of a big family. It is no longer a problem of whether I love. You are simply part of me, and as I trust you and we are part of an enterprise, everything that is decided is correct.

“Fidel was also the man who was facilitating the country’s dream. For example, one of the great things he invents is literacy, which is very beautiful. Or distributing land to the peasants. Who wasn’t going to agree with that? Anyway, it was a very nice moment, really.

“Fidel could have become one of the Christs of human history, he was going down that road. People loved him, gave thanks to Fidel, ‘Fidel, my house is your house.’ All of this went on, things that would make you cry. And socialism seemed like the realization of man as a species, the political and cultural realization. Open hospitals for everyone. Although he didn’t create the hospitals, they were already there, and, well… the doctors left, because he harassed them. So that all the intelligence of the country would leave for good, and he could start over with people he had shaped from scratch and were in his debt.

“But, yes, it was beautiful. And we were making history, on the other hand. You don’t take money with you, but you do take glory. We were rebuilding the world. The great epoch.”

***

The life of Rafael Alcides is an excuse for nostalgia. If we continue with Rilke, it can be said that Alcides has been nothing more than the final verses of Duino’s Eighth Elegy: “Who has turned us upside down like this, so that, no matter what we do / we keep the attitude of one who is leaving?”

Everything – born on June 9, 1933 in a hamlet in Oriente province, “immense savannah with only ten or twelve houses” – begins, transpires, and ends this way: “I cannot stop being from Barrancas./ From Barrancas that today only exists in my dream.” We understand that fidelity to moral convictions is, then, a relatively comfortable and minor task for those who have known how to save that which is is most difficult: the integrity of their being.

Alcides is a pillar of memories, and time has finally forgiven him. Regina, his wife, describes him: “Another of the things that makes him extraordinary has to do with his appearance. When we started our relationship 24 years (!!) ago, my niece, with all the candor of ten years, wondered if he was Eliseo Diego. He wore then a venerable white beard and was unexpectedly balding. His contemporaries seemed like younger brothers. It turned out the joke was on them as he didn’t get any older while others lost their freshness, hair, pounds, physical and/or mental agility and for a long time the tables have been turned. That, despite a copious medical record very well concealed.”

He grew up in a clapboard house with a thatched roof and dirt floor. His first heroes were the heroes of Cuban Independence: Maceo, Gómez, Calixto García. Rafael and his brother Rubén were vying for the leading roles in their games, even coming to blows if necessary. Both always wanted to be Maceo, until Rafael convinced Rubén to assume the role of Ignacio Agramonte: young and beautiful.

“That was,” he said, “our childhood literature. And our cinema.” He already assumed Cuba as a vast fiction, the raw material with which his inventiveness would be dispatched.

He attended primary school in Bayamo, and in 1946, when about to finish high school at the Escuelas Pías de San Rafael y Manrique in Havana, he returned to Oriente – only to leave again. In Poema de amor por un joven distante [“Love poem by a far-away young man”] – dated 1989 – Alcides recreates as a protective father the archetypal arrival to Havana of excited young people of the province – that first, terrifying, Balzaquian clash with the city so many times evoked. But in reality, like Whitman, in the harmonious salutation to his fellow man, Alcides speaks to himself, and comforts and embraces the young man “solitary and lonely, the loneliest of men” — himself — on that day “longer than a century” of June 22, 1952.

In that decade, his baptism of fire was the struggle against the Batista dictatorship, clandestine activity, and membership in rebel groups of action and sabotage. There are moments, situations that haunt him, furies of youth that today he would not subscribe to, that he does not even mention. But they were violent years, tense, he in the prime of his age. What else could he do but offer himself to the fierce ritual of justice?

“Once we were at the university, the police came and started shooting. We threw ourselves to the ground and then, the next day, we saw that the bullets had hit a meter above our heads. But we came to know it the next day. With life, it happens to you exactly the same way.”

In the first years of the Revolution, Alcides was assistant to Manuel Fajardo Sotomayor (Commander of the Rebel Army), participated in the Literacy Campaign, assumed positions of a political cadre in the ORI (Integrated Revolutionary Organizations), and wrote two initiatory and forgettable poetry books: Himnos de Montaña [“Mountain Hymns] (1961) and Gitana [“Gypsy Woman”] (1962). In 1963 he published El caso de la señora [“The case of the lady”] in Unión magazine, a poem that caught the attention of Nicolás Guillén – his close friend – and stood out in the effervescent literary panorama of the moment.

Alcides assumed the conversational language that, first in an organic way – starting with his generation, the so-called “Generation of 1950”: Pablo Armando Fernández, Manuel Díaz Martínez, Roberto Fernández Retamar, Fayad Jamís, Heberto Padilla, etc. – and then later imperatively (due to stylistic fashion or expressive obedience with which to praise the socialist project) would come to rule the Cuban poetic discourse for a couple of decades.

At the same time, within the ICRT (Institute of Radio and Television), he wrote scripts and conducted En su lugar la poesía, a radio program on which several of the most important poets of Latin America were guests. In addition, he amassed narrative projects. In 1965 he delivered, with the tagline Brigada 2506 [the name of the exile group that carried out the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961], his novel Contracastro to the Casa de las Américas contest. Mario Vargas Llosa defended it tooth and nail, but such a title aroused resentment and, the prize being declared null, Alcides was awarded an honorable mention.

“The novel was not a counterrevolutionary novel — far from it. Maybe it was the doing of Haydee Santamaría (president of Casa de las Américas), a wonderful woman, very big, but for whom Fidel was untouchable, and the name must have seemed like a rumble, an elephant in a glassware shop. Later I learned that while on a trip to Vietnam [Fidel] asked for a copy so that he could read it, and decided that yes, they could publish it.”

But he was asked to change the title, and Alcides did not accept.

— Maybe that’s where your disappointment with the project begins.

“No, it’s not that. It was a very individual thing. We are still in January of ’65, a romantic year, and any individual could come up with anything.”

In 1967, La pata de palo [“The wooden leg”] appeared on the Letras Cubanas imprint, and the first poem, El agradecido [“The grateful one”] is enough: “My whole life has been a disaster/ that I do not regret./ The lack of childhood made me a man/ and love sustains me./ Prison, hunger, everything:/ all of that has been good for me :/ the stabs in the night/ and the unknown father./ And so from what I had/ is born this thing that I am: a very little thing, it is true,/ but huge, grateful as a dog”.

Since then, Alcides is a parable. Diaphanous, but deep. Assertive, but suggestive. The straight line of his actions, the clarity of his verses, end up creating an immensity.

He broke down the epic patiently. He sat at his kitchen table, took the Homeland, put it in the coffee grinding machine, and began to crush at times with the left, at times with the right, and so on. His colloquialism is ambidextrous. He equally claims the legitimacy of agitating himself as though a blind and universal god to whom everything is incumbent, as the possibility of composing, like the industrious potter, the exquisite daily piece.

“The wooden leg” found immediate homage in Guillén’s late exercises, such as En algún sitio de la primavera [“Somewhere in Spring”], and in Taberna y otros lugares [“Tavern and other places”], Roque Dalton’s main collection of poems. About Carta hallada en los bolsillos de un monje [“Letter found in the pockets of a monk”], one of the poems in the book, Virgilio Piñera said: “The reader who tries to find the ’trembling’ of St. John of the Cross, the ’imagery’ of Góngora, the frisson (goosebumps) of Baudelaire, the flares of Rimbaud or the ’silences’ of Mallarmé would understand nothing of this ’Carta’ [’Letter’] in which poetry is anything other than trembling, imagery, frisson, flares, and silences. And perhaps there is all that (…), but inserted into words that are not the words that the aforementioned poets used in their songs”.

In the braid (impossible to remove without destroying it) of History in capital letters and lyrical will that is the existence of Alcides, “The wooden leg” was followed by 1968, the Soviet tanks in Prague, the Cuban government’s approval of the invasion, and with it the pragmatic dagger of realpolitik destroying the brave illusions of the poet.

There would come the parametración imposed the literary and artistic field, the established and legislated censorship, the accelerated Stalinization of society, the most abusive methods of alleged ideological re-education, and the famous Padilla case – the author challenged for his “critical and anti-historical” literature, imprisoned under accusations of subversive activity, then pushed to publicly read a self-criticism in the purest of Soviet styles – and the Western intelligentsia’s immediate and majority divorce from the Revolution.

“We must understand the enormous cruelty that this meant, the wound it made in the field of culture. Everything went through a black hole. Someone moved the needle of the trains and diverted the route. The experience of the USSR began to be duplicated and the martiano program [the study of José Martí’s legacy] was betrayed: “a republic with all and for the good of all,” an economic program for small and medium-size business owners. This shows how that very human process, which seemed to be led by men, was carried out by So-and-Sos who wanted to look like divinities.”

In 1970, intent on publicizing his disenchantment, Alcides presented at the National Union of Writers and Artists (UNEAC) a notebook entitled The City of Mirrors, and was predictably rejected “as nihilistic, as improper of the New Man”.

Knowing that he would also be set apart, he decided to set himself apart. He would not visit UNEAC again. He would not submit books to any publisher. He would not attend any exhibition or cultural event. He would not be seen in cinemas, concerts, or public events. Thus began the longest inxilio [internal exile] of Cuban literature.

“The alternative would have been to plant bombs to destroy what I had helped build, and that I was never going to do.”

Alcides wrote radio scripts from his home and wrote prophetic verses in the most complete and conscious solitude. He subjected his soul to a disciplined military regime. He wrote: “The past and the future have already passed./ Everything we had we lost,/ and it was more than we could have./ We have this rumor. This / lot of sorrows that the wind spreads, / immemorial, without time./ This rumor / of what was / life before the future came.”

These were scary times and no one paid visits to anyone.

“César López and Pablo Armando saw each other more or less, from time to time. Manuel Díaz Martínez was stuck in a radio station without being able to put his name to his work, Heberto (Padilla) translated Maiakovski without being able to sign his work, Virgilio at that time also translated without being able to sign his work — everyone was very scattered. It was an offensive against intellectuals who had applauded the process, who had fought in Playa Girón [Bay of Pigs], who had slept rough, by the sea. People who loved the Revolution. These writers began to have ideas, to make critical literature, and they annoyed those who were already seated on the chair of Stalinism. That’s the whole story.

Later, many of the defenestrated intellectuals would be reinstated and would gladly accept the state’s perks. But not Alcides. An eminently sentimental — even melodramatic — poet, and with enough courage to write the fieriest confessions and walk the edge of any excess. But possessing, also, a cold lucidity. He believed that what the Revolution should expect from true revolutionaries was not faith anymore, but doubt: “A poem can be/ a machine of emotion/ or a machine of intelligence./ (Emotion passes).”

***

“Poetry is mixed with the story, with the novel, with everything. Poetry is given in fits and starts, it is like love. You have to write as you feel it. This is your chance, you will not be born again. That’s the secret. It doesn’t matter that others don’t see it. The creator risks his death, others risk their lives. Poets who today seem transcendent, tomorrow are forgotten. It happens with all authors. Poetry is the mystery, the gift that the word has to captivate. But it’s not a safe place. Today they can throw you kisses, give hugs, but tomorrow… There are so many poets out there. That’s why you have to take a chance. You don’t write for now, not for me, not for you, not for anyone. You are writing for your contemporaries — that is, the future. Sincerity. If it goes well, it goes well. If not, then no. Do not lie. Do not lie. He who lies will have his hand withered,” says Alcides, the noble conversationalist.

***

It is easy to trace the transcendent events in Alcides’ life, because they are all in his work, without disguise. He married Teresa – “Without solitude to deceive,/ today Teresa and I do not eat and we drink the poem/ made stew and made coffee that is how it feeds,/ and we laugh at how they are heated in a jar / or fried in a pan with butter / our next Complete Works” – and had with her the most famous of his four children: the painter Rubén Alcides.

When Teresa – several years divorced from Alcides – emigrated in the early 90s with the son they had together, Alcides composed Carta a Rubén, one of the most shocking elegies about the main trauma of the recent Cuban family: “But we, / we alone, / the sad, / the mournful ones / in what homeland are we now? (…) / The homeland, far from what you love? (…) / Where you live between walls and locks / it is also exile…”.

He sang, also, to the helpless flower (Canto para los dos) [“Song for the two of us”], to the tomb of his only general (En el entierro del hombre común) [“At the burial of the common man”], and even to the ministers, in a poem where he confesses: “Every time I hear about a friend / who is going to be made a minister, / someone erases a part of my life …” If we review the updated list of cultural commissars or retroactive sacred cows – a good part of the Generation of 1950 – we will see that power has been erasing Alcides more than should be erased from a man.

But in 1984 – years of a certain thaw already – “Agradecido como un perro [Grateful as a dog]” appeared, an indelible explosion. Reviews rained down and young and gallant readers, stunned, broke their fast with Alcides. In the title poem, the Revolution is mentioned. However, the poem does not wither, which is what usually happens, but the Revolution endures. The Revolution, after so many flat balladeers and grandstand impostors, finally owed survival to a dissident.

At the end of the eighties, believing that idle abstention made no sense, and driven by what he described as “the deceptive winds of Perestroika,” Alcides reconnected with the UNEAC and participated in meetings and congresses.

“My attitude had been that of someone who did not want to charge against what he had loved and continued loving, and for which he could still give his life because he had hopes that we would rectify it.”

Returning to the world, he found Regina, then an official of the Ministry of the Interior. She knew his poems inside out, and the gravitas, the manifest disinterest of Alcides in standing out, the silences interrupted only by his affable radio-announcer voice, ended up captivating her.

“I saw him for the first time at a wake and we didn’t speak, but I was very impressed by his concentrated expression, by himself, sitting in a Calzada y K [a Havana funeral home] armchair. Then we were introduced to each other at UNEAC and there was empathy, but no more. We met again through the complicity of a friend on 31 December 1988, and the rest, as they say, is history.”

In 1991, after the events of the “Letter of the Ten” [also called the Declaration of Cuban Intellectuals] – expulsion from the UNEAC, administrative sanctions, false accusations, and a shameful campaign to discredit a dozen intellectuals who dared to sign and disseminate what, according to Manuel Díaz Martínez himself, a signatory, was no more than a “list of moderate demands to the government” – Alcides concluded that everything would remain the same and so he again began to prefer his solitude to the company of colleagues whom he still loved but whom, in the best of cases, the pusillanimous silence turned into accomplices.

Around that time, Letras Cubanas released the forgotten notebook La ciudad de los espejos [“The city of mirrors”], but with a much more bitter title, which summarized the annoyances of Alcides: Nadie [“Nobody”]. It was his last book to be published by a Cuban publisher and he would never appear again in any public space. They once tried to recognize him with the National Prize for Literature and he rejected it.

As alternative avenues of expression opened up in Cuba, Alcides moved from silence to critical participation. He has held nothing back — not in interviews, not in articles, not in talks or events to which the political opposition invites him. During the last 23 years, his poetic work has only seen the light of day thanks to the Sevillian publisher Abelardo Linares, who one day knocked on his door and rescued him.

***

On the occasion of his 80th birthday, Regina wrote: “Alcides is incapable of boarding a bus, a shared taxi (almendrón), or a called taxi (panataxi); he is incapable of walking even 200 yards to meet a celebrity. Instead, he is an extraordinary host, so warm and attentive, who immediately makes even new acquaintances feel comfortable.”

“In this time of ideological polarization, he keeps affection intact and that intense way of loving, be it for a high government official or a senior opposition leader in exile. He forgives (but does not forget, he has an excellent memory) some fool elevated? from bison poet to official who from his new position has allowed himself to treat him coldly. He still regrets the errata by omission of the dedication to Roberto Fernández Retamar in a poem from a book recently published in Colombia.”

A year later, some online media outlets published the following email, signed by Alcides:

“Havana 30 June 2014

Miguel Barnet, Poet

President, UNEAC

“Friend Miguel: In view of the fact that my books are no longer allowed to enter Cuba either through customs or by mail, which is the same as prohibiting me as an author, I resign from the UNEAC. You will also find in this envelope the Commemorative Medal of the 50th anniversary of the UNEAC which, as a founder, belongs to me. The rest of that mansion that was so mine in another time, are my memories, and these, being personal, will leave with me. Among those memories, that of the good friends found in the UNEAC of that time, treasures of my youth, what I have left of that great failed dream, figures whom I love even if they do not think like me and who love me, even if they do not dare to visit me. That is all, Miguel. Anticipating interpretations that would omit the text of this irrevocable resignation, I have gone ahead and made it public.”

And it has continued. Filmmaker Miguel Coyula’s YouTube channel has been publishing, since the end of 2015, some short videos – powerful visual haikus – in which Alcides talks about the lost dream of the Revolution, the people, beauty, Fidel Castro, artists. Similarly, the Verbum publishing house has just launched a poetic anthology of his, with definitive overtones, of which Alcides has only one copy.

Still, resentment is something he knows nothing about, and he fervently believes in God.

***

—Over time, you have gone further than any of your generation.

“No. I have advanced just like everyone else. I’m pretty sure we all think the same. In Cuba, there are only two dissidents: Fidel and Raul Castro. The rest of us agree that this does not work. What happens is that some dare to say it and others do not, because some are inside the game and others outside. Since I don’t need to take trips, nor do I accept trips, nor do I want a different house, nor do I aspire to be given a car, and I don’t even have a landline, I can say it.”

—But that’s going further.

“It is not.”

***

Manuel Díaz Martínez has said of him: “Rafael Alcides treasures still – they live on in his conduct and his writing – the rebellions and longings that were once the currencies of our already dismantled generation. It should not surprise us, then, that this Caribbean Ulysses continues to dream, in the grotto of Polyphemus, of reaching Ithaca. Across the Atlantic I discover him, a navigator of stubborn dignity, resisting the siren songs in a muddy sea of betrayals and surrenders.”

***

—Did you ever think about leaving Cuba?

“No, never. I am from here. Honestly, I wouldn’t know how to live outside of Cuba. But the problem is to continue fighting. It doesn’t matter if it’s here or there. That isn’t important. And I believe that those who fight for change, be it here or there, have the same right.”

—Do you feel alone at times?

“No, I don’t feel alone. I have many friends outside. But the friends from before no longer exist. They are a part of the before times. They don’t come here.”

—Do you still love them?

“Yes, I love them in the past. What has been, not even God can erase, and I respect it all. Now, those friends no longer visit me. If we run into each other, by chance, some of them hug me, others turn away. I have become invisible.”

—And how does that make you feel? Sad?

“Not even, not anymore. I realize that it can’t be otherwise. I realize that they are afraid. It makes me pity them (a little) because I know that they have not stopped loving me. Because I have not stopped loving them. I love them in the past, but I love them all the same. I greatly respect the choices of others, in every sense, but I also respect my right to disagree. If in the next government we will be as intolerant as we have been in this one, I’ll take this one, because I already know it more or less.”

—The radical position of the old exiles is not very convincing to you. “No, I don’t believe in radicalisms, radicalisms are stupid. We don’t realize it, but we have lived through a great tragedy. Today the word Patria — fatherland — doesn’t exist. We have drama. And literature — the novel, poetry — is made with drama, with pain. This is coming to an end. The time has come to start telling about it.”

Translated by Alicia Barraqué Ellison and others.