The Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, also known as the Mandela Rules, set international standards to ensure that prisoners are treated with humanity and dignity. No form of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment is permitted. Practices such as indefinite solitary confinement, confinement in dark or always illuminated cells, and corporal punishment are prohibited. In addition, food or drinking water must not be reduced as punishment. Solitary confinement is defined as keeping an inmate without meaningful human contact for at least 22 hours a day. Prolonged solitary confinement refers to any isolation lasting more than 15 consecutive days. In Cuba, the law allows solitary confinement for up to three months, which does not meet these international standards.

Rule 45 of the Mandela Rules states that solitary confinement should only be used in exceptional cases, as a last resort, for as short a time as possible and with independent review. It should be authorised by a competent authority and should not be imposed on prisoners with physical or mental disabilities, women or children. However, the length of solitary confinement in a punishment cell in Cuba reveals a worrying difference between official regulations and actual practice. Under Cuban law, solitary confinement can last up to three months, which significantly exceeds the UN Mandela Rules, which consider prolonged solitary confinement for more than 15 days to be a violation of human rights.

Cubalex has documented numerous cases of persons deprived of their liberty who have suffered solitary confinement in punishment cells for periods that far exceed both national regulations and international standards. Among these testimonies, the cases of political prisoners such as Félix Navarro, who was in a punishment cell in Guantánamo prison from continue reading

May 11 to December 16, 2003, accumulating more than seven months in solitary confinement, stand out. Alfredo Felipe Fuentes and others imprisoned during the

Black Spring of 2003 endured more than ten months in punishment cells in Guanajay prison. Alcibiades Idelmaro Brizuela, for his part, spent seven months in a punishment cell in Kilo 8, Camagüey, and then a year in solitary confinement on a floor of that prison.

Lisandra Rivera spent three months and ten days in a punishment cell in Mar Verde women’s prison, Santiago de Cuba, in early 2017.

Arbitrary and precarious conditions

The reasons for placing a prisoner in a punishment cell are often arbitrary and varied, ranging from hunger strikes and rights claims to political activism and telephone complaints to independent media or family members. In some cases, prison authorities resort to this measure pre-emptively based on their assumptions about the prisoner’s behaviour.

The conditions of the punishment cells in Cuba are extremely precarious and degrading. The dimensions of these cells are very small, with some measuring only two metres wide by less than four metres long, including both the bathroom area and the dormitory. In some cases, these dimensions are even smaller, exacerbating the feeling of claustrophobia and extreme confinement. Sanitary facilities are equally poor; instead of proper toilets, there is a simple hole in the floor, known as a ‘Turkish bath’. The water supply is scarce and provided only once a day for a short period of time, making it difficult to maintain personal and cell hygiene.

Hygiene in these cells is deplorable. Inmates must clean their spaces with whatever means they can get, often facing insanitary conditions and insect infestations. Lack of adequate lighting and insufficient ventilation further aggravate living conditions; many cells have no windows or only small openings for ventilation. Furnishings are minimal and rudimentary: beds are often made of concrete or metal, often without mattresses, forcing inmates to sleep on hard, uncomfortable surfaces.

Torture and Punishment Practices

The use of solitary confinement in Cuba is not only limited to isolation, but often includes additional practices of torture and punishment. Prisoners may be handcuffed in painful positions and left like this for long hours, as was the case with Lisandra Rivera, who was handcuffed for 26 hours without access to food and water.

Treatment during solitary confinement is cruel and dehumanising. Deprivation of drinking water is also used as additional punishment, forcing inmates to consume contaminated or insufficient amounts of water. Cells are cold and damp, and adequate bedding is not provided. In many cases, prisoners are left in their underwear, intensifying their physical and psychological suffering. Reports of violence are alarming: inmates may be taken to punishment cells after brutal beatings by guards. Torture techniques are common and include hanging prisoners by handcuffs, throwing them down stairs while handcuffed, and handcuffing them face down, causing extreme pain and severe injuries.

In addition, prisoners on hunger strike are subjected to sleep interruptions, frequent cell changes and force-feeding, practices that seek to break their will and resistance. The psychological impact of these inhumane conditions and prolonged isolation is devastating, causing severe stress, anxiety and other psychological problems, often leaving lasting effects on the mental health of those affected.

Impact on prisoner health

The impact of prolonged solitary confinement on prisoners is devastating, affecting both their physical and mental health. Constant anxiety, tachycardia and other psychological problems resulting from the extreme stress of conditions of confinement are common. In addition, lack of adequate medical care and wilful neglect further aggravate the health conditions of prisoners, who often do not receive treatment for their ailments while in solitary confinement.

Incompatibilities between Rule 45 of the Mandela Rules and the Cuban Penal Enforcement Law

There is a clear incompatibility between the provisions of Rule 45 of the Mandela Rules and Articles 122, 127 and 137 of the Cuban Penal Execution Law. The discrepancies are significant and affect both the duration and conditions of solitary confinement.

Duration of Isolation

Article 122 of the Cuban Penal Execution Law allows solitary confinement in a security cell for up to 15 days for men and 10 days for women, juveniles under 20 years of age and those over 60 years of age. This provision deviates from Rule 45 of the Mandela Rules, which prohibits prolonged solitary confinement, defined as more than 15 consecutive days. Furthermore, Rule 127 defines solitary confinement as a disciplinary measure in more restrictive conditions and separate from the rest of the prison population. Article 137 allows the use of solitary confinement for up to three months to protect the physical integrity of the prisoner or the security of the prison, which far exceeds the acceptable limit under the Mandela Rules.

Rule 45 vs. Cuban Law: A Conflict in the Use of Isolation

The first incompatibility lies in the duration of solitary confinement. While Rule 45 states that prolonged solitary confinement should not be permitted, the Cuban Penal Execution Law allows for solitary confinement for up to three months. This represents a significant discrepancy and a possible violation of international human rights standards.

Secondly, Rule 45 specifies that solitary confinement should be used as a last resort and only in exceptional cases. However, the Cuban Penal Execution Law allows for the use of solitary confinement as a relatively common disciplinary measure, indicating that it is not necessarily considered as a last resort.

Isolation without independent review in Cuban prisons

Another incompatibility is the lack of independent review. Rule 45 requires that the imposition of solitary confinement be reviewed by an independent authority to ensure its proper use and prevent abuse. In contrast, the Cuban Penal Enforcement Law gives the head of the prison the authority to decide on solitary confinement without the need for external and independent review, which could lead to arbitrary decisions.

Protection of vulnerable groups

In addition, Rule 45 prohibits the solitary confinement of prisoners with physical or mental disabilities that could be aggravated under such a regime, as well as women and children in certain cases. Although the Cuban Penal Enforcement Law excludes some vulnerable persons, such as pregnant women, prisoners under the age of 18 and persons with disabilities, it also allows for exceptions that could lead to arbitrary use of solitary confinement without adequate external control.

Conclusions

In summary, the main incompatibilities between Rule 45 of the Mandela Rules and the Cuban Penal Enforcement Law lie in the permitted duration of solitary confinement, the lack of requirements for its use as a last resort, the absence of independent review and the insufficient protection for vulnerable groups. These discrepancies show that the Cuban Penal Execution Law does not comply with the international standards established by the Mandela Rules, which can lead to situations of abuse and violation of the human rights of prisoners.

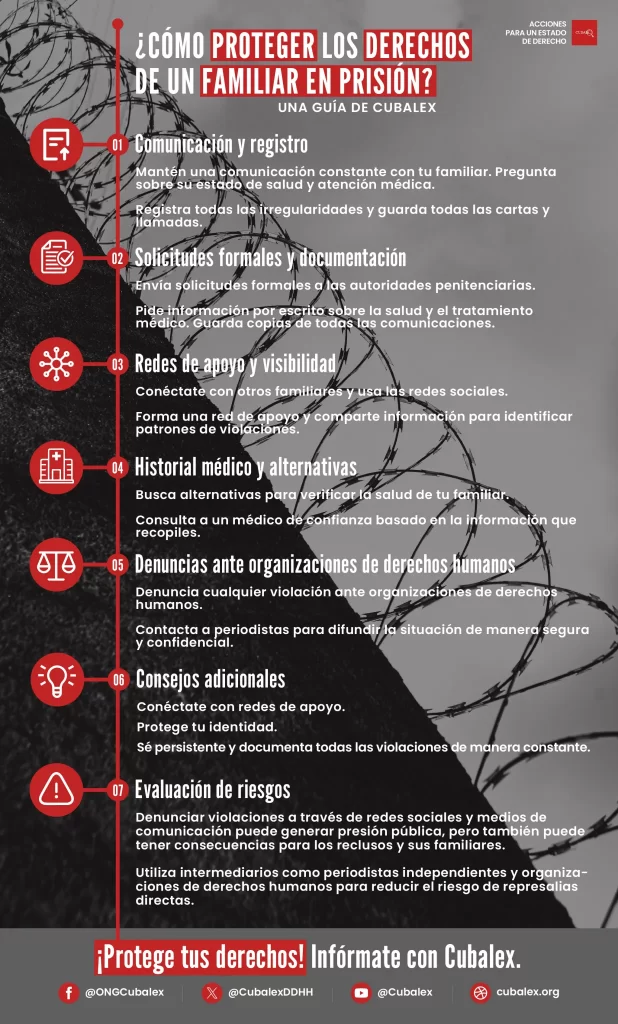

It is crucial that the Cuban authorities undertake reforms to bring themselves in line with international standards, thus ensuring humane and dignified treatment of all prisoners. Independent monitoring and strict implementation of rules prohibiting prolonged solitary confinement and torture are essential steps towards the protection of human rights in prisons.

As citizens, it is important to be informed about these rights and to report any observed violations. Human rights organisations can provide support and advice to report these abuses and work towards a more just and humane prison system.

The post Conditions of isolation and punishment in Cuban prisons appeared first in Cubalex.

Translated by GH