After clicking on the video, click “Watch this video on YouTube” and it will play for you.

Category: Miguel Coyula

The Arrogance of Cuba’s Political Police

![]() 14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Generation Y, Havana, 17 January 2020 — In the last decade there have been several recordings of police interrogations that Cuban activists have managed to make and bring to light. In many of them, State Security officers are heard intimidating, threatening and behaving themselves like the owners and lords of the whole country, above the law, above human life and above citizens’ rights. But the audio achieved by the photographer Javier Caso during an “interview” with the political police is invaluable as a testimony and as an X-ray of an entire era.

14ymedio, Yoani Sanchez, Generation Y, Havana, 17 January 2020 — In the last decade there have been several recordings of police interrogations that Cuban activists have managed to make and bring to light. In many of them, State Security officers are heard intimidating, threatening and behaving themselves like the owners and lords of the whole country, above the law, above human life and above citizens’ rights. But the audio achieved by the photographer Javier Caso during an “interview” with the political police is invaluable as a testimony and as an X-ray of an entire era.

The Cuban, who lives in the United States and is the brother of the renowned actress Ana de Armas, recently visited the island and repeatedly contacted actress Lynn Cruz and film director Miguel Coyula. It was enough for him to meet with his friends of a lifetime to receive a summons from the Department of Immigration and Foreigners. Once there, a script was developed that was well known to dissidents, opponents and any independent journalist who has ever been summoned to this type of police trap.

The audio recorded by Caso, who by the mere fact of recording the voices on a device shows great courage, manages to convey the absurdity of the situation, the arrogance of the interrogators and that atmosphere where the individual is at the mercy of a surveillance device and control capable of ignoring the Constitution, the Criminal Code and whatever legal resolution there is on this Island. The young photographer met two men who personify the true power that controls Cuba, above deputies, ministers and presidents. continue reading

It is a grotesque and cruel face that springs from the impunity of a repressive institution that has been running freely for decades

The officials are ridiculous, they mouth barbarities such as that the Cuban police are the fifth best in the world or dare to decide who can be called an artist or not, although they themselves may not know one iota about creative expressions or contemporary art.

The great triumph of Caso is to take, with apparent naivety but with much intelligence, the conversation to a point where the seguros have to take off their masks and show the true face hidden under bureaucratic formalities and an apparent respect for order. It is a grotesque and cruel face that is born from the impunity of a repressive institution that has been running freely for decades and whose arrogance ends up opening it to ridicule in this conversation.

Since new technologies broke into the Island, there have been many testimonies (photos, audios, videos) that attest to the lack of a framework of rights in which we Cubans live, but this recording has a special merit. In addition to the quality with which one listens and the equanimity of the person being questioned to get the officials to expose themselves, this testimony causes an outrage that is not easily placated. The more we hear of it, the greater is a rage that grows and becomes a decision and a conviction: we cannot allow the political police to continue ruling Cuba.

_________________________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.

Discussion of the Film “Nadie” with Miguel Coyula and Lynn Cruz

Blue Heart / Corazon Azul

CORAZON AZUL (BETA TEASER Ver 1.0) from Producciones Pirámide on Vimeo.

From Miguel Coyula and Lynn Cruz and cast

Mainstream Avant-Garde Films In Latin America

Miguel Coyula, Film Inquiry Magazine, 15 January 2019 — What is considered Latin American art cinema today? Who defines the accepted hegemonic profiles of the films that receive funding and are shown all over at European film festivals? For the past 15 years or more, film institutions in the West, whose mission is discovering new artists with a different point of view, have developed a particular aesthetic favoring.

Strong intellectual opinions are not to be found in Latin-American films with observational narratives, minimalist mise-en-scène, natural lighting, no incidental music; with long shots of characters wandering a landscape where poverty and social and political issues might be implicit but not overtly developed. In general, this fashionable aesthetic usually favors the disappearance of manipulation by an auteur, contradicting the very nature of searching for a personal voice.

Third World Art Film

The result is that many of these films end up looking very much alike, dismantling the very concept of auteur cinema for which they were supposedly chosen. This new market of fashionable Latin American art cinema is becoming not unlike the bubble that plagued the visual arts, confirming the existence of two markets: commercial mainstream films and the emerging niche market of the “third world art film”. This market is designed for a somewhat-educated first world audience looking at Latin America as a sensorial landscape, rather than investing effort to learn its intricacies and contradictions.

It even goes as far as suggesting changes to filmmakers in order to fit the mold. Let’s take some examples in Cuba. Cuban filmmaker Armando Capó´s script for Agosto received support from several institutions, both in Europe and the US, but several changes were requested to fit their conception of what the film should be. Capó complained that it was very difficult to maintain his vision under these circumstances.

Films with a fragmented narrative, strong use of montage, stylized lighting, upper middle-class characters, or strong intellectual opinions are immediately discarded, as if that aesthetic can only be the province of developed nations in the West.

And what are these first world audiences conditioned to expect from third world cinema? A distant window, peeking at another culture from the safety of high above. This is not too different from decorative art: nothing too uncomfortable for either the eyes or the mind to digest. The poverty of the working class is almost always seen through this condescending gaze; the characters suffer and yet rarely are aware of the forces that create their agony, and even less are they ready to confront those forces.

Outside of Pornomiseria

Cuban filmmaker Jorge Molina, whose work has been characterized by an extreme mixture of explicit sex, gore, science fiction and horror, can’t find any institutions willing to fund his films. Resultedly, he’s ended up in no man’s land since his work is deemed too extreme for both mainstream and arthouse tastes.

The term “Pornomiseria” (misery-porn) has been criticized by many Latin American filmmakers and scholars. The term is a critique to filmmakers who abuse the underdevelopment and marginal settings in Latin-American films as an excuse to draw the attention of a foreign audience. Many filmmakers are even crafting their projects from the initial stages to fit this mold and get funding, while a few filmmakers use it as only as a selling point to later revert to their original concept once they obtain funding.

Carlos M. Quintela´s La Obra del Siglo is an example of a film that managed to escape the nature of its original conception. The minimalist story of three men, three generations, living in a small apartment building, gained an enhanced political context when the filmmaker discovered documentary footage of the Cienfuegos Nuclear Power Plant and subsequently relocated his story to this new setting, creating a hybrid of fiction and documentary. However, it is doubtful that the Huber Bals Fund, the institution that funded the original script, would have approved the increased complexity of the finished film.

This is another precedent on how important it is to divorce from written ideas. In today’s film world, I find that the most interesting projects are improved with the chemistry of improvised elements finding their way into the narratives. Of course, this makes it rather difficult when institutions require a detailed description on paper of what will be on screen.

Filmmakers And Film Festivals

It’s difficult today to find anything completely original. It’s the combination of influences which combined can create a true unique voice, but in an increasingly globalized world even some of these alternative films are rapidly labeled, and sales agencies jump in to make a business out of it, even if it’s just for a niche audience. The filmmakers then remain happy with the formula they concocted and very seldom venture into truly new territory.

In this world, the filmmaker has a much higher rate of success by befriending festival programmers and learning their tastes, sometimes valuing them more than artistic quality. Even festival awards are given because of pre-arranged benefits with sales agencies that act as distributors because they know the films are not commercial enough to release. These films remain available only to the academic world, since domestic distribution won’t make dividends for a sales agency. Needless to say, these films hardly even play in their native countries.

On top of that, submissions fee at international film festivals are almost a must. Only a very small number of films that have been programmed by many festivals have been submitted via the official submission channel. The rest are either recommended or the festival takes interest in contacting the filmmaker directly. The submission fees of rejected films end up as a source of income to the festivals. In other words, rejected independent filmmakers end up funding festivals where they don’t participate.

Carlos M. Quintela´s latest film The Wolves from the East is a mature story about isolation and nostalgia. The film takes place fully in Japan with a Japanese protagonist. If Yasujirō Ozu had made this film, the press would revere it, but a Cuban filmmaker made it and that’s not what international audiences expect from him. So the film has fallen into a cultural and geographical limbo, which has made the film difficult to program at festivals.

Conclusion

Now, for my agitprop rant: I find the vast majority of supposed “art films” highly irritating, because the compromises become more and more detrimental to our truly exploring the medium. A few programmers and curators seem to be fixated on an aesthetic regardless of what an intelligent audience (devoid of snobbish classism) would be capable of enjoying. These people are as responsible as the Hollywood suits for delaying the evolution of cinema language.

An independent filmmaker must be independent not just in the way he or she obtains financing, but mostly in form and content.

About Miguel Coyula

Miguel Coyula is a Havana-based Cuban filmmaker, published author, and Guggenheim Fellow whose lauded work has been screened and awarded around the world. Most recently he produced a webseries and documentary feature (Nadie) on the late poet Rafael Alcides, the latter of which screened at MoMA and won Best Documentary at the Global Film Festival in Santo Domingo. Currently Coyula is working on his fourth feature, Corazon Azul (Blue Heart).

Original in English by the Author

A Clandestine Work for Freedom of Expression

![]() 14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Miami, 3 November 2018 — Teatro Kairós continues to defy censorship and police repression. After months of rehearsals and study, last weekend he premiered Patriotism 36-77, directed by actress Lynn Cruz, in the abandoned buildings of the former Circus School of the Higher Institute of Art.

14ymedio, Luz Escobar, Miami, 3 November 2018 — Teatro Kairós continues to defy censorship and police repression. After months of rehearsals and study, last weekend he premiered Patriotism 36-77, directed by actress Lynn Cruz, in the abandoned buildings of the former Circus School of the Higher Institute of Art.

Cruz told 14ymedio that “when the news came out of Decree Law 349 that makes the right to do theater in homes impossible,” she was forced to be more creative when choosing the place of presentation.

“I realized that the corridors and halls were ideal for simulating a prison and the galleys. On the other hand, natural light solved all the problems and the acoustics, with a sound design that started from the environmentitself that we could create with the elements of the work, we could do without the music. continue reading

We already had to principal resolved so as not to have to do a generatl rehearsal and avoid being discovered. This is the most risky and performative part of the show. If they make the private spaces illegal, we can take the abandoned State spaces and they can be occupied by the artists,” the actress and director of the piece explained.

The piece premiered last Sunday without advertising, almost in secret, and only a select group of guests attended. The cast of the work consisted of Cruz herself, the actress Juliana Rabelo and the painter Luis Trápaga.

The actress arranged with a group of taxi drivers to collect the guests house by house to help them get to the Circus School, far from the center of Havana.

“The work addresses the psychological and physical violence exerted by the State on people who dare to raise their voices, and in the middle of the process I discovered a Swiss director Milo Rau who did a work, Five Easy Pieces, on pedophilia, starring children. The critics talked about the feeling of suffocation it left, because the piece was about the submission and power of the adult over the violated child.

I said to myself: “I want the spectators to feel what a prisoner of conscience feels in Cuba. Beyond the words I was interested in being suggestive with what was happening in the scene,” she explains.

For Lynn Cruz the bringing of the guests provoked that sensation that she was looking for, something that for her was a “maxim.” The audience, who never knew where they were going or with whom they would share the car that would transport them, would experience that “transit to a place of distrust, fear, uncertainty.” That is, she says, what the people who went felt.

The characters are a critical painter, played by Luis Trápaga; a student of humanities and daughter of a dissident, played by Juliana Rabelo, and Lynn’s character, who is a human rights activist and daughter of a member of the Communist Party.

To achieve her scenographic idea, Cruz thought of everything in direct opposition to the theatrical tradition.

“I had thought of a design with lights that simulate a tunnel, which was difficult to do in a house without losing the visual quality because sometimes one fails, there, to create the atmosphere you need in a play. It happed to me with Los enemigos del pueblo (The Enemies of the People). We were not satisfied with the visuality, and thanks to some young photographers I was able to have an ideal scenario that they offered me in secret, and when I was filming [the film Blue Heart] with Miguel [Coyula] I started studying the ruins.”

Patriotism 36-77 came about largely thanks to a fundraiser on the Verkami platform , where it was described as “a work for the right to freedom of expression in Cuba.”

Lynn Cruz has personally experienced censorship in several creative projects promoted outside the cultural institutions of the country and has faced the persecution of State Security, which has interfered occasionally to prevent presentations scheduled by her on behalf of her independent theater project.

____________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

Independent Cuban Films Continue to Make Headway Internationally / Lynn Cruz

Havana Times, Lynn Cruz, 23 August 2018 – When darkness seems to hang over us a little heavier, there is a truth that shines through: “The essential thing is to work, to create.”

It has been over a year now since our documentary Nadie, which we tried to screen at a private venue: “Casa Galeria El Circulo”, suffered police repression. Then, during the Mar del Plata International Film Festival, we received a strange email to cancel the screening of this same documentary at the festival, after it had initially been accepted.

After hearing our accounts about censorship not only on the island but abroad too, visual artist Tania Bruguera told us about the persecution her own work had suffered and how this had gone beyond seas and borders and that this should be reported. continue reading

This is how the idea for the Cuban Cinema under Censorship exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, MoMa, which was held last March, was born.

A total of 8 movies were shown as part of Bruguera’s project which she put forward with the Hannah Arendt International Institute for Artivism (INSTAR), which started operating at the end of 2017 in Havana.

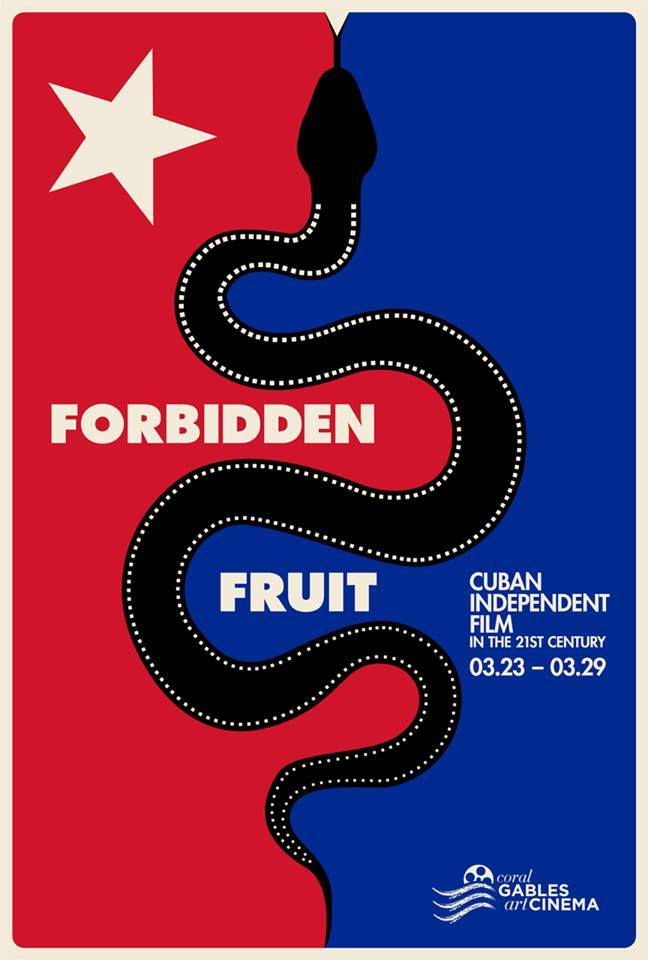

Then, in April, Cuban-Lebanese-American Nat Chediak, an intellectual and film enthusiast, founder of the Miami Film Festival, organized the first Independent Cuban Film Festival outside of Cuba under the name, Forbidden Fruit.

The festival took place at the Coral Gables Art Cinema in Miami, which Chediak is currently responsible for programming, and was also curated by critic Alejandro Rios.

At this time, a new copy of the movie produced outside of Cuban institutions, is headlining at the World Cinema Amsterdam Independent Film Festival which is underway right now and will end on August 26th. It also includes movies which have had protection from Cuban institutions, the most noteworthy being Sergio y Serguei(RTV Comercial) by Ernesto Daranas or Ultimos Dias en La Habana by Fernando Perez (ICAIC).

In this way, it has become evident that independent filmmakers are beginning to become a force to be reckoned with. Bruguera has kicked off a new funding campaign to continue developing Cuban film, which is deprived in Cuba and only survives thanks to filmmakers’ own initiatives.

Today, the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) only produces historical movies. Alejandro Gil’s movie about 8 medical students who were shot during Spanish colonial times is currently in the post-production phase as is Jorge Luis Sanchez’ movie which focusses on the character of Julian del Casal, a poet who represented the move towards modernism in Cuban literature; as well as Rigoberto Lopez who is working on a movie about Ignacio Agramente, a hero of Cuba’s independence wars.

ICAIC doesn’t seem to have any interest in integrating new filmmakers either, and the way scripts are chosen within this institution is still unknown.

In contrast, INSTAR’s deadline for submissions will end on September 8th. Filmmakers interested in taking part can fill out a form online or download one as a PDF file. This is essentially an opportunity to make your first movie.

This opportunity offers a niche for everyone who wants to make their first feature movie, short movie or documentary. It’s a question of thinking about film from its genesis outside of government institutions.

Few outdoors shoots, a reduced technical team, would be strategies that allow these movies to be made.

Now is a good time for Cuban film thanks to these initiatives by Cubans who have managed to pave the way for Cuban film abroad and try to continue developing and offering opportunities to the Seventh Art created on the island, with or without the protection of Cuban Film Laws.

Note: This article, in its English translation, is taken from The Havana Times.

Making a Movie in Cuba with Porno Para Ricardo / Lynn Cruz

Havana Times, Lynn Cruz, 17 August 2018 – Last Saturday, we filmed a new scene for the movie Corazon Azul (Blue Heart) by Miguel Coyula. This time, we went to the Playa neighborhood in the capital where Paja Recol is located, a recording studio and Gorki Aguila’s home, leader of punk-rock band, Porno para Ricardo.

It’s incredible how the fact that this band can’t play on the island has become second nature.

Like anyone else from this punk genre, he rips every taboo and social convention to shreds. Everything is game for these musicians. Sex, Fidel Castro, a State Security agent, an official or even the outrageous figure of a district representative, who in reality is actually a city mayor. continue reading

It’s best if he doesn’t talk about you, my friend used to say. To be honest, it was the first time I saw this band play live. They played the same part of the song “Tipo Normal” (Normal guy) chosen by Coyula for a scene in the movie, over and over again.

A boundless energy and Aguila’s special charisma, along with Renai Kayrus and Yimel Garcia, filled the room. In my mind, one question kept going round and around: what’s going on in this country?

I still can’t understand how, in all this time, I’ve only known about their work via USB drives, when they are literally only a few minutes away from my house.

How is it possible that Cubans can’t see these three musicians play, who only rehearse because the Cuban government doesn’t let them play?

The country has been drained over time. Now, we are only left with wrong ways. There is no reason why these musicians continue to be confined to a room in an apartment.

Art doesn’t make sense if it can’t be shown. At this point, we will never know what this band could have been if they had enjoyed full freedom.

They are witty, intense and original. While talking to Gorki about their impact on me, he told me in his humble way: “If you only knew, people have told me this, that they like to see us play.”

He also told me that when they were allowed to play concerts, they were always thinking about their performance. One time, they showed a guitar at the beginning and told the audience: “This Soviet guitar needs to die”.

They gradually distanced themselves and ended up becoming radicalized. Having celebrated its 20th anniversary, this band carries the tragic sign of what it means to be ahead of your time.

To be honest, they are missionaries at the wrong time because Cuban reality was greatly marked by the disastrous ‘90s. And in 1998, Porno para Ricardo was founded.

That’s to say, that Gorki, Kayrus and Ciro Diaz Penedo (also a founder) were already in the future. They were singing from the past to a post-revolutionary Cuba.

Nobody on the island had ever dared to mock Fidel Castro before like they did. This is important because eliminating political humor was one of the first changes that Castro made to the press.

The Revolution had to be serious. Coyula’s movies have a special connection to this band. You can see this in his movies Memorias del Desarrollo (2010) and Nadie (2017).

Now, in Corazon Azul, they not only come together with the same energy, but Porno para Ricardois responsible for creating part of the movie’s soundtrack and they will also appear playing on a TV channel, created within the movie’s plot.

Slowly, Cuba’s truly underground and alternative world will come together like a puzzle. Prison, persecution, repression are all constants for the majority of artists in this universe that have an influence, not in the fringes of the city, but outside of the Museum of Cuban Socialism’s political establishment.

Note: This article, in English, is taken from The Havana Times

The Stranger, a Poem by Rafael Alcides

The Stranger. A poem by Rafael Alcides, read by Lynn Cruz, filmed by Miguel Coyula.

Nadie, with Rafael Alcides, Chapter 1: The Beautiful Things / Miguel Coyula

Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency Nullifies Dismissal of Actress Lynn Cruz

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 21 May 2018 — Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency has ruled in favor of Lynn Cruz with regards to the claim presented by the actress after the Performing Arts Artistic Agency (Actuar) put an end to her contract last April without complying with the mandatory 30-day notice period. The artist was informed of the decision on Friday, 11 days after the five members of the court agreed with her.

14ymedio, Havana, 21 May 2018 — Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency has ruled in favor of Lynn Cruz with regards to the claim presented by the actress after the Performing Arts Artistic Agency (Actuar) put an end to her contract last April without complying with the mandatory 30-day notice period. The artist was informed of the decision on Friday, 11 days after the five members of the court agreed with her.

The document issued by the Labor Justice Agency specifies that there was a violation of Resolution 44 that regulates labor relations in organizations overseen by the Ministry of Culture.

For Lynn Cruz, this ruling makes clear that Jorge Luis Frías Armenteros, director of Actuar, violated article 297 of the penal code with the “unwarranted imposition of a disciplinary measure.” continue reading

The president of the Labor Justice Agency, Iván Rodríguez, told Cruz that after this ruling, “it did not make sense to go to the municipal court” because Actuar was going to continue to “represent her without problems.”

As of now, the actress could be hired again but after what happened she does not trust that she will be able to return to her work, because she believes that the agency can work behind her back to prevent her name from being chosen by a director who is interested in her work.

For Cruz, there is no way to repair the “psychological and moral damage” this measure has caused her, in addition to the “loss of work” she suffered in this case.

The actress also wonders if this step was taken to protect Frías, that is to avoid a criminal complaint. This Friday, when asking Ivan Rodriguez if the director of Actuar would be sanctioned for his error, the president of the Labor Justice entity replied that the agency “could not sanction its own director.”

“Evidently they are protecting Frías, the procedure he used in my case was clumsy since the contract was violated, but there is an intention to protect him after that blunder he committed,” Cruz believes. Cruz is of the opinion what was decisive in her case — unlike the cases of Ariel Ruiz Urquiola, Oscar Casanella or Yanelis Nuñez — was that she recorded the public hearing and “made the recording public,” a hearing in which the director acknowledged his error in not notifying her 30 days in advance before canceling the contract.

At the public hearing Frías said that Actuar’s decision to terminate her contract had been taken due to the actress’s “demonstrations on the internet” against “the main leaders” of the Party and the government and acknowledged that they had made a mistake” in the procedure.”

Lynn Cruz (born 1977) has developed her career between theater and cinema, although she has also participated in some television shows. She has worked on several Cuban films including Larga Distancia and La Pared.

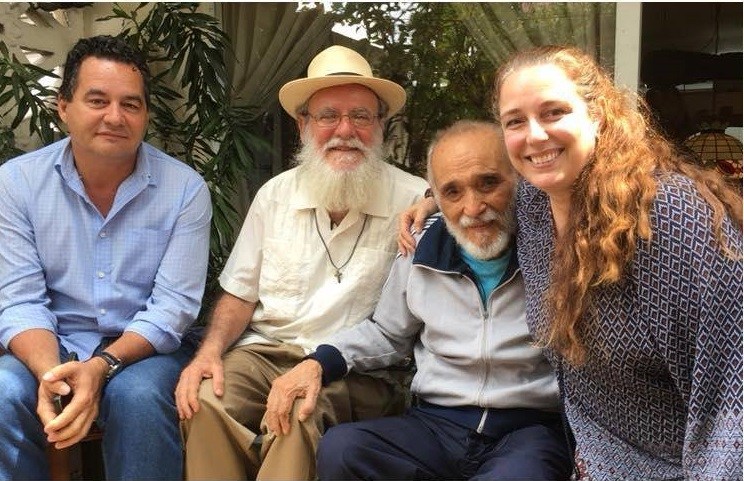

Cruz has a special performance in the documentary Nadie, directed by Miguel Coyula, which includes testimonies of the poet Rafael Alcides, an intellectual censored on the island. This film was presented at the independent El Círculo gallery with the presence of Alcides himself, without major incidents. However, another presentation was repressed by State Security, which blocked public access.

_______________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

“They’re Using You”

Havana Times, Lynn Cruz, 5 February 2018 — I recently read Tania Bruguera’s statements about an artist’s rights. One of them referred to the artist’s right to dissent.

Within an authoritarian system, the artist begins to live a double dissidence, first in art, then in society.

Having your own voice is always grounds for suspicion among members of your artistic community, but when it’s the Government who has the last world with regard to a phenomenon which only concerns art, like deciding who is a revolutionary and who isn’t, then this does put us in a delicate position. continue reading

The two times I invited my closest colleagues to the alternative venue: “Casa Galería El Círculo,” (led by artists and activists Luis Trapaga and Lia Villares), some have told me: “I don’t go to those places.” Others have just respond with silence or stop calling you. And if worst comes to the worst, they repudiate you.

There were actors, theater directors and filmmakers among those I had invited to watch my play “Enemies of the People.”

After the scandal (produced by the presence of State Security forces and police at the home/gallery’s doors, saying that it was a counter-revolutionary play), an actor I had invited, who ironically also makes theater at his home, called me to say that: “He felt used by me.”

He was quite frankly terrified when he saw himself in a video that the house’s owners and a journalist had decided to film, as their only form of defense and way to denounce this injustice.

Plus, this actor is someone who has strong opinions about Cuban reality, who I had always had an open and straight-to-the-point dialogue with before the event. I even told him that something similar had happened at this same place when the documentary Nadie was scheduled to be screened, which the creator, filmmaker and theater director Miguel Coyula, couldn’t even attend.

Even so, he had a scornful attitude towards me: “I feel used.”

What do these words mean in our context? If a lie is repeated enough times, it becomes the truth. Fidel Castro transformed the Cuban people into an army, whose soldiers didn’t fight against an enemy, but fight each other instead, while he took all of the glory.

The subtext that lies between the lines of this phrase: “They’re using you” is “Let me be the only one to use you.” Thus, artists who are condemning or approving slander campaigns against their colleagues, who are being persecuted for defending the right to make political art, become pawns in a game of established power which isn’t only being played by arts institutions, but by the Cuban government itself.

“Enemies of the People” deals with an event that continues to go unpunished today: the sinking of the 13 de marzo tugboat on July 13, 1994.

Back then, Castro condemned the US Government instead of the captains of the attacking boats (encouraged by him even?), the real ones responsible for the genocidal event which caused half of those on board to die from drowning, including children. However, survivors’ testimonies are pristine proof of the event.

However, Article 3 of the Cuban Constitution states: “In the Republic of Cuba, the sovereignty resides in the people, from whom all of the power of the State emanates….” it goes on to say: “All citizens have the right to fight, using all means, including armed struggle, when no other recourse is possible, against anyone attempting to overthrow the political, social, and economic order established by this Constitution”… and ends by saying: “Cuba shall never return to capitalism.”

This explains why the people responsible for the sinking were labeled “heroes” and haven’t been sentenced to this very day. We mustn’t forget that the brains behind this system were the brains of a lawyer.

Note: English translation from the Havana Times which also published the original in Spanish.

Cuban Regime Frees Activist Lia Villares

Diario de Cuba, Havana, 23 December 2017 — Activist Lia Villares was released this Friday morning after being detained since Wednesday, activist Rosa María Payá Acevedo said in her Twitter account.

Diario de Cuba, Havana, 23 December 2017 — Activist Lia Villares was released this Friday morning after being detained since Wednesday, activist Rosa María Payá Acevedo said in her Twitter account.

Villares, in addition, was fined 500 pesos by the authorities, according to Martí Noticias.

During the arrest, “her interrogators told her that she had committed crimes, and in order to prove it to her they showed her a photograph that she had taken some time ago with two policemen. In the photo she appears with a fan with the logo of the CubaDecides opposition initiative” directed by Payá Acevedo, according to the Miami media. continue reading

In the cell where she was detained, the activist wrote with a stone on the wall “Art Yes, Censorship No. I am free.”

“They tell me that this is a damage to property and carries a fine of 500 pesos,” she explained.

Villares was arrested Wednesday along with other artists when they tried to attend the staging of the play Psychosis.

Among those arrested and then released were Tania Bruguera, actress Iris Ruiz (protagonist of the monologue that was to be performed), Adonis Milán (director of the play), poet Amauri Pacheco, art historian Yanelys Nuñez, another person identified as José Ernesto Alonso and the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara.

The plot of the piece revolves around a person enclosed in a very small space showing obvious signs of madness who wants to leave the place.

The version that was presented was inspired by the events of 2010 at the Psychiatric Hospital of Havana, popularly known as Mazorra, where 26 patients died of hunger and cold. In the monologue direct allusions were to be made to Raúl Castro and terms such as “dictatorship” were used.

The independent gallery El Círculo is subject to constant repression by the regime. State Security also closed this independent space in April to prevent the presentation of the documentary Nadie, by Miguel Coyula, which deals with the life of the poet Rafael Alcides.

Likewise, the political police set up another operation last November to prevent public attendance at the work “The Enemies of the People” directed by the documentary filmmaker Miguel Coyula, which fictionalized the final minutes of Fidel Castro.

Cuban State Security Blockades a Play in El Círculo Gallery (Updated)

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 24 November 2017 – Cuban State Security managed to limit attendance to just two people to last night’s premiere play The Enemies of the People. The police cordon set up around the El Círculo gallery in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood, where the play was going to be performed, worked as a method of pressure to intimidate would-be audience members.

14ymedio, Havana, 24 November 2017 – Cuban State Security managed to limit attendance to just two people to last night’s premiere play The Enemies of the People. The police cordon set up around the El Círculo gallery in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood, where the play was going to be performed, worked as a method of pressure to intimidate would-be audience members.

Activist Lía Villares, owner of the house that that provides the premises for the theater, related via twitter what happened when members of the political police were stationed in the vicinity of the Villares’s house and pressured the numerous guests to not enter. “Everything that happened yesterday in the presence of witnesses and neighbors demonstrates the agonizing situation of cultural rights and freedom of expression in Cuba,” denounced Villares. continue reading

Despite the pressures, the activist said that actress “Lynn Cruz could not have given a better performance.”

The work, interpreted by Cruz and directed by filmmaker Miguel Coyula, offers “a timely vision of Cuban society subjected to a dictatorship,” explain its organizers.

Cruz reincarnates Charlotte Corday, a famous character of the French Revolution and who murdered Jean-Paul Marat. On this occasion, however, instead of Marat, Fidel Castro is the target of her action.

In her Twitter account Lia Villares said that the staging “almost starred the henchmen of Section 21,” the Department of State Security that deals with surveillance against opponents. “They did not allow anyone to enter” the El Círculo Gallery, lamented the activist.

The piece also has an incognito character, played by the musician Gorki Águila who delivers an emotional reading of the list of names of the 41 victims of the 13 Tugboat 13 de Marzo, sunk in July 1994 by four official boats that used water cannons to attack the boat on which the victims were trying to flee the country.

Those killed in the tugboat incident were between the ages of 6 months and 50 years. After a week in which the official media silenced what happened, Fidel Castro described the performance of the crews of the boats that attacked the tugboat as a “truly patriotic effort.”

The independent El Círculo gallery is a frequent target of police operations. Last April, a large deployment of troops prevented the public from attending the screening of the documentary Nadie (Nobody) directed by Coyula, which presents the life of the poet Rafael Alcides, censored in the official publications.

__________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

Anime Animates Coyula / Regina Coyula

Jorge Enrique Lage interview with Miguel Coyula (fragments) 2

Miguel Coyula: [… the cinema where I first encountered anime.] [… like the video games of the late eighties and early nineties, the anime of that time had no big budgets for a fluid animation at twenty-four frames per second, Disney-style. Then they went to a visual design and assembly and sound very often shocking.] [… in the subconscious, that left a mark on the film I make.]

For me it is very important to work the space and design the storyboard to the last detail, so that no image is repeated during the editing of a scene. That is something that comes from anime, and the comic book in general. Each panel expresses an idea, just as in literature each sentence expresses something different.

As for video games, the animation was even more limited: 2D, but that same limitation …] [… it made me shape an aesthetic where the image is as loaded as possible with small elements that add density to the setting.

[… the anime stories often left me with a bitter taste. Yaltus, known as Baldios outside Cuba, was a film that marked me a lot. Its apocalyptic and depressing ending, where the earth is completely contaminated with radioactivity, left me in a state of discomfort that I have pursued in my films.

[… one of the most striking films for me, for the stylistic collage it represents, was Belladonna of Sadness, 1973. For some reason it’s the 70’s that keeps calling me over and over again as a source of inspiration.

Site Manager’s note: Once all the fragments of this interview are translated (by different volunteers) we will unite them in order, in a single post.