After clicking on the video, click “Watch this video on YouTube” and it will play for you.

Category: Rafael Alcides

Discussion of the Film “Nadie” with Miguel Coyula and Lynn Cruz

Posthumous Novel by Rafael Alcides, Against Death, Against Oblivion / Ramon Fernandez-Larrea

Translated from* from El Nuevo Herald, Ramón Fernández-Larrea, 8 November 2018

When one receives a novel – written by a friend who is a poet, or by a friend who has been and is forever a great poet – with the title Contracastro, one could never imagine that it is a love story, and not a pamphlet of accusations against power, nor the political testament of a worthy man, with a vertical and honest position.

And if that novel is also the posthumous work of that poet friend, which is also like a last will, and also, a very old story that Rafael Alcides began to ruminate on in the convulsive first years of the 1960s, and which he spent his life writing and rewriting, the result is a kind of testament, because this novel could be, or is also, the novel of our lives.

On the cover of the print edition it is noted that Contracastro is “A novel written in reverse.” Why? I suspect that it has to do with what Alcides himself says in the public history of the book: “In this second version the old love story is supported with very slight additions. Not so the context, this time evoked from today by Tom, already an old man, in a mega-Miami where he has been among the city’s forgers… For that first version, consistent with my political views of the time, the novel was nothing more than the many other pamphleteering-style texts of the time, against capitalism and the bourgeoisie.” continue reading

And Rafael Alcides continues telling us that “because of its title it frightened the Casa de las Américas officials when they saw it appear in the Literary Contest of 1965,” where “The juror Mario Vargas Llosa, who nominated it for a Prize, managed to obtain an Honorary Mention.”

What changed then? The world changed, Alcides changed. The years passed and the luminous future never arrived on the coasts of the island. Fatigue and disappointment arrived. And the masks fell from those heroes who wanted us happy all the time. And then came the time to tell, openly, the rending of the protagonists’ journeys to nowhere, the many protagonists of the other major novel, the epic of a people who emigrate, of families that are torn apart and walk through these worlds, without being able to tell their loved ones in a letter, all the love they still have.

Contracastro, published today by Eriginal Ediciones, is an inquest into Cuban history after 1959, told in first person, but in two alternating times, but, always in the background, it is a passionate story of love, sex, disgust and illusions, especially of lost illusions that the protagonist is capable of shouting to the four winds: “Burn down the world if they want, I have you.”

Contracastro is that then and this now. They are Tom and Carla in a provincial Miami that has been filled with Cubans who expect life to change in the next sixty minutes so that they can return to their country. A country that has already been filled with Russians, Chinese, Americans, abandoned houses, streets that will be, from then on, only in a bloody memory.

“Even though here in Miami they hate the word revolution,” writes the author, “it is here, nevertheless, where the Revolution really is. The Revolution with capital letters. In Cuba, the Revolution has already passed and what there is is the complete opposite of the ideals of democracy, present since the Guáimaro Charter of 1869.” … And at the end of that statement made by Tom, the protagonist, thinking like Rafael Alcides, or Alcides himself stuck in the skin and blood of Tom, one can read: “So while we can not return to Cuba, I will continue to consider myself a man from Guáimaro, a follower of Agramonte, a soldier of Céspedes, that is, a revolutionary.”

Contracastro is, in short, the legacy of Rafael Alcides, a man who lived and died telling his truths in Cuba today, and that was uncomfortable for the authorities, because honesty, in times of disappointment, is, at the very least, suspicious. Here the poet leaves us this intense story of a love that was and was not. A testimony against death, against oblivion. And we must read with gratitude to its author, to discover who we have been or who we are now. To know which side of History we are on. Or, better, to check, with pain and bitterness, which side of this story is ours.

Pacts / Regina Coyula

Regina Coyula, Havana, 5 October 2018 — State Security has not only forbidden me to travel to Spain (where I should have been on the 25th of September), but “el compañero who attends me” (i.e. my own personal State Security minder) has been promising me since Tuesday the 25th that this prohibition would be lifted, a falsehood that discredits his institution still more, and at the very least calls into question his professionalism.

Contrary to my desire, I have postponed this trip I’d dreamed of. If this were a country of laws and rights, someone would have to compensate me, because I don’t have so much as a citation for stepping on the grass, much less is there a reason to limit my movements, but being a dissenter – and writing about it – makes me an enemy of the State.

All that’s left for me – because I didn’t do the thing they told me not to do – is to lodge a complaint with the Citizenship Service of the Ministry of the Interior and make it known among my friends.

Alcides already expressed it in an epigram: The pacts between bandits and knights do not work and the knight ends up in jail. The bandit will never become a knight but the knight ends up becoming a bandit.

Independent Cuban Films Continue to Make Headway Internationally / Lynn Cruz

Havana Times, Lynn Cruz, 23 August 2018 – When darkness seems to hang over us a little heavier, there is a truth that shines through: “The essential thing is to work, to create.”

It has been over a year now since our documentary Nadie, which we tried to screen at a private venue: “Casa Galeria El Circulo”, suffered police repression. Then, during the Mar del Plata International Film Festival, we received a strange email to cancel the screening of this same documentary at the festival, after it had initially been accepted.

After hearing our accounts about censorship not only on the island but abroad too, visual artist Tania Bruguera told us about the persecution her own work had suffered and how this had gone beyond seas and borders and that this should be reported. continue reading

This is how the idea for the Cuban Cinema under Censorship exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, MoMa, which was held last March, was born.

A total of 8 movies were shown as part of Bruguera’s project which she put forward with the Hannah Arendt International Institute for Artivism (INSTAR), which started operating at the end of 2017 in Havana.

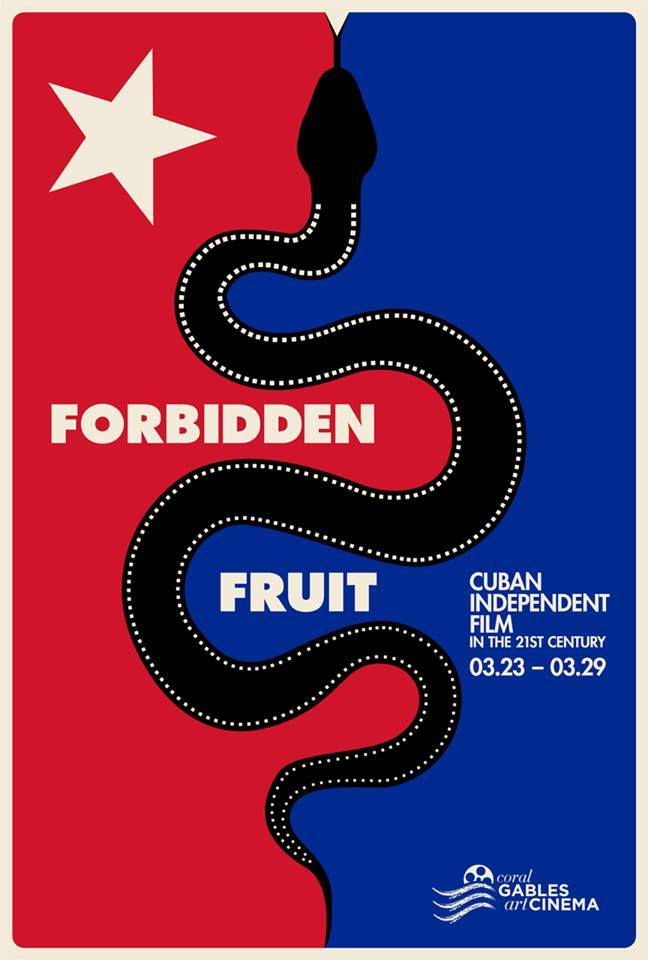

Then, in April, Cuban-Lebanese-American Nat Chediak, an intellectual and film enthusiast, founder of the Miami Film Festival, organized the first Independent Cuban Film Festival outside of Cuba under the name, Forbidden Fruit.

The festival took place at the Coral Gables Art Cinema in Miami, which Chediak is currently responsible for programming, and was also curated by critic Alejandro Rios.

At this time, a new copy of the movie produced outside of Cuban institutions, is headlining at the World Cinema Amsterdam Independent Film Festival which is underway right now and will end on August 26th. It also includes movies which have had protection from Cuban institutions, the most noteworthy being Sergio y Serguei(RTV Comercial) by Ernesto Daranas or Ultimos Dias en La Habana by Fernando Perez (ICAIC).

In this way, it has become evident that independent filmmakers are beginning to become a force to be reckoned with. Bruguera has kicked off a new funding campaign to continue developing Cuban film, which is deprived in Cuba and only survives thanks to filmmakers’ own initiatives.

Today, the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) only produces historical movies. Alejandro Gil’s movie about 8 medical students who were shot during Spanish colonial times is currently in the post-production phase as is Jorge Luis Sanchez’ movie which focusses on the character of Julian del Casal, a poet who represented the move towards modernism in Cuban literature; as well as Rigoberto Lopez who is working on a movie about Ignacio Agramente, a hero of Cuba’s independence wars.

ICAIC doesn’t seem to have any interest in integrating new filmmakers either, and the way scripts are chosen within this institution is still unknown.

In contrast, INSTAR’s deadline for submissions will end on September 8th. Filmmakers interested in taking part can fill out a form online or download one as a PDF file. This is essentially an opportunity to make your first movie.

This opportunity offers a niche for everyone who wants to make their first feature movie, short movie or documentary. It’s a question of thinking about film from its genesis outside of government institutions.

Few outdoors shoots, a reduced technical team, would be strategies that allow these movies to be made.

Now is a good time for Cuban film thanks to these initiatives by Cubans who have managed to pave the way for Cuban film abroad and try to continue developing and offering opportunities to the Seventh Art created on the island, with or without the protection of Cuban Film Laws.

Note: This article, in its English translation, is taken from The Havana Times.

Memory of the Future / Regina Coyula

Regina Coyula, 29 June 2018 — Alcides was not a censored one (although undoubtedly he would have been), but a quarter of a century ago, by his own will, he insiled [internally exiled] himself from Cuba’s cultural life. As part of that insile, he did not let himself be seduced by the national literature prize about fifteen years ago.

He felt rewarded knowing that his book Agradecido como un perro (Grateful as a Dog) was exchanged for cigarettes in the Combinado del Este prison in the late eighties, that it traveled in a plastic bag with the scarce possessions of a rafter, or was requested in the neighborhood; that kids would arrive from all over the country who discovered in a bookstore second hand.

His books are now collectors’ items, a writer unknown to the youngest and unpublished after 1990, if not for the Sevillian editor Abelardo Linares knocking on the door one day and later others appeared in Logroño, and because of the insistence of the unforgettable Albertico Rodríguez Tosca, in Colombia.

Alcides was unable to leave the house to meet a celebrity. Instead, many will remember an extraordinary host, both friends and recent arrivals. He lived as a poet, always wanting to see poetry in everyday events. Some verses saved for posterity. Poetry driven away, he dedicated himself to to finishing enormous drafts of novels left in the pipeline in the hurry to live, and now left to me, filled with notes for a huge job ahead.

Many thanks to all of you who have sent me your admiration and regret.

In Tribute to Rafael Alcides, Cuban Poet and Writer and Wonderful Man

Today Translating Cuba is dedicated to Rafael Alcides, who died yesterday. We are republishing articles by and about him, and you can also do your own search of past articles on this site by going to this link.

The following “Author’s Biography” was written several years ago and is not up-to-date.

Rafael Alcides was born in Barrancas, municipal district of Bayamo (Cuba) in 1933. A poet and storyteller, he was a master baker in his teen years. He has worked as a farmhand, cane cutter, logger, wrecking crew cook, and manager of a sundries store in a cane-cutters’ outpost.

continue reading

Among his most recently-published titles are the poetry collections, GMT(2009), For an Easter Bush (2011), Travel Log (2011), Anthologies, in Collaboration with Jaime Londoño (2013), Conversations with God(2014), the journalistic Memories of the Future (2011), the multi-part novel, Ciro’s Ring (2011), and the story collection, A Fairy Tale That Ends Badly (2014).

As of 1993, he had been employed by the Cuban Institute of Radio & Television for more than 30 years as a scriptwriter, announcer, director and literary commentator when, at that time, he ceased all publishing and literary work in collaboration with the regime in Cuba. As a participant in numerous international literary events, Rafael Alcides has given conferences and lectures in countries in Central and South America, Europe, and the Middle East. His texts have been translated into many languages. He was honored with two Premios de la Crítica, and a third for a novel co-written with another author. In 2011 he received the Café Bretón & Bodegas Olarra de Prosa Española prize.

The Stranger, a Poem by Rafael Alcides

The Stranger. A poem by Rafael Alcides, read by Lynn Cruz, filmed by Miguel Coyula.

Writer Rafael Alcides Dies in Havana at the Age of 85

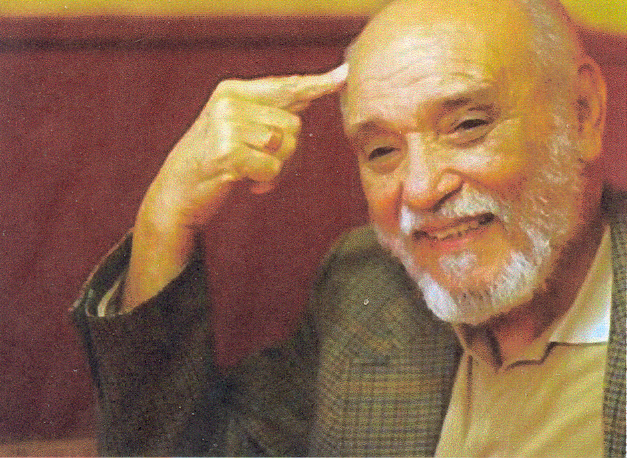

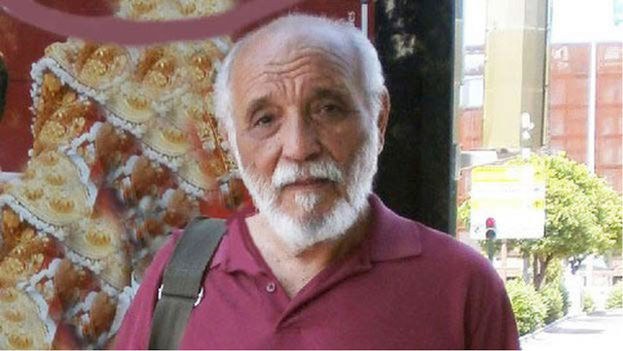

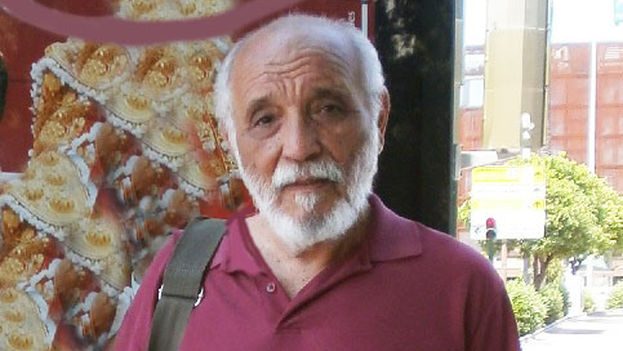

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 20 June 2018 — Ten days after his 85th birthday and after a long battle with cancer, the poet Rafael Alcides died at his home in Nuevo Vedado on Tuesday afternoon, his son Rafael confirmed to 14ymedio. Sources close to the family explained that there will be no funeral and that his ashes will be scattered in Barrancas, in the east of the island, where he was born on 9 June 1933.

14ymedio, Havana, 20 June 2018 — Ten days after his 85th birthday and after a long battle with cancer, the poet Rafael Alcides died at his home in Nuevo Vedado on Tuesday afternoon, his son Rafael confirmed to 14ymedio. Sources close to the family explained that there will be no funeral and that his ashes will be scattered in Barrancas, in the east of the island, where he was born on 9 June 1933.

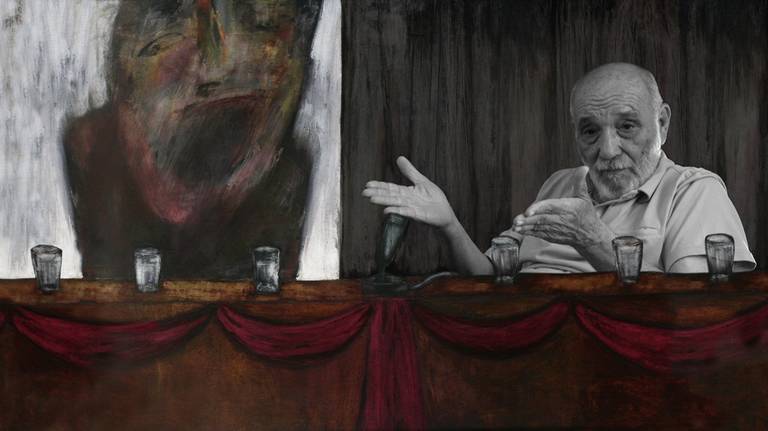

“He did not like tributes,” says filmmaker Miguel Coyula and author of the documentary Nadie, based on an interview with Alcides that lasted more than two hours. With this work, presented in the independent gallery El Círculo in Havana, Coyula addressed the biography of the poet and novelist, especially his long years as a censored writer. continue reading

Rafael Alcides began his literary career with the magazine Ciclón (Cyclone) and successfully published some 60 books, including Himnos de montaña (Mountain Hymns) (1961) and La pata de palo (The Wooden Leg) (1967).

He began his fall from grace with the regime when, in the 80s, the poet set aside ideology and expanded to less political issues, publishing Agradecido como un perro (Grateful as a Dog) (1983), Y se mueren y vuelven y se mueren (They Die and Come Back and Die Again ) (1988), Noche en el recuerdo (A Night to Remember) (1989), Nadie (Nobody) (1993).

By 1983, when his poetry collection Agradecido como un perro appeared, the author had already suffered, for decades, the institutional silence that greeted his work, because of his openly critical positions on the Cuban Government.

From 1993 on, he abandoned all publishing collaborations on the Island and in 2011 he won the Breton Café & Bodegas Olarra de Prosa Española Award.

In 2014 his books published in Spain were seized from his wife, the blogger Regina Coyula, every time she tried to bring them into Cuba. For this reason he submitted his resignation from the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC), which he had been a member of for years, saying that banning from the island his books published abroad was the same thing as banning him as author.

The poet published a letter, which he addressed to Miguel Barnet (president of UNEAC), in which he explained his reasons and returned the Commemorative Medal of the 50th anniversary of the UNEAC, which he had been granted as a founder of that government institution.

The letter to Barnet makes clear the ideological disenchantment of one of the most important poets of the 50s Generation: “Among these memories are those of the good friends I made among the members of the Association back then, treasures of my youth that are all that remain of that great, failed dream, people I love though they do not think the way I do, and who love me also, even if they dare not visit me.”

In speaking of the writer and poet, Cuban writer Virgilio López Lemus says that when Alcides published Agradecido como un perro he became a reference poet for the generations born between 1946 and 1970. López Lemus describes this work as a “long and intense poem in which the lyrical subject appears in a confessional attitude and at the same time as a witness, where he includes social life, family life, love and friendship (or is it one of the two?), and above all the warmth of a man who expresses himself with his skin open to the world, whether he receives wounds or caresses.”

____________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

Nadie, with Rafael Alcides, Chapter 1: The Beautiful Things / Miguel Coyula

Rafael Alcides, Who is a Very Important Person / Regina Coyula

Note: This article is being republished from 2013. Rafael Alcides passed away yesterday, 19 June 2018.

My husband is not just any writer. He belongs to the generation known as “The Generation of the ’50s,” a rather arbitrary poetic grouping that started with Carilda Oliver (1922) and ran through David Chericián (1940). His generation’s peers — if they haven’t died or emigrated — have received the National Literature Prize and enjoyed social and official recognition. This is one of the reasons he is an extraordinary writer. Not only that he wasn’t seduced by the siren song of the National Prize ten years ago. Not only that he willingly “inxiled” himself from Cuba’s cultural life for twenty years and is not published in Cuba. continue reading

For him, the prize has been that his book Agradecido como un perro (Grateful As a Dog) was traded for cigarettes in the Combinado del Este prison in the late eighties, and asked around for; kids coming from the provinces discovered him by chance in a second-hand bookshop. His books today would be collectors’ items, of a writer unknown to the young and unpublished after 1990, if it weren’t for the Seville publisher Abelardo Linares who knocked on our door one day.

He is not a run-of-the-mill writer. Foreign publishers are highly sought after, their visits to Cuba put them in a position to receive a ton of unpublished and published texts from hopeful authors who either fete the foreign visitor or put a Santeria spell on them.

He is not a run-of-the-mill writer. Foreign publishers are highly sought after, their visits to Cuba put them in a position to receive a ton of unpublished and published texts from hopeful authors who either fete the foreign visitor or put a Santeria spell on them.

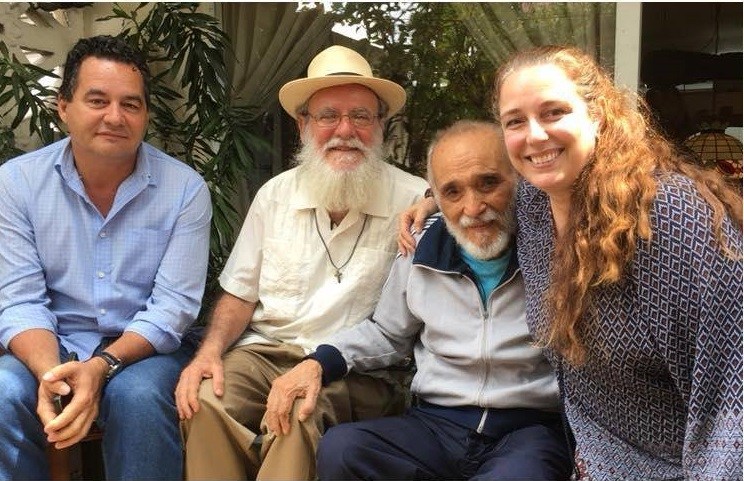

Alcides is incapable of boarding a bus, a shared taxi (almendrón), or a called taxi (panataxi); he is incapable of walking even 200 yards to meet a celebrity. Instead, he is an extraordinary host, so warm and attentive, who immediately makes even new acquaintances feel comfortable.

In this era of ideological polarization, he maintains an intact and intense affection for those he loves, whether a high government official or a senior opposition leader in exile. He forgives (but does not forget, he has excellent memory) some highbrow (?!) silliness from a fledgling poet to a functionary who from his new position has been allowed to treat him coldly. He will regrets the error of omission in the dedication to Roberto Fernández Retamar in a poem in a book just published in Colombia.

Another of the things that makes him extraordinary has to do with his appearance. When we started our relationship 24 years (!!) ago, my niece, with all the candor of ten years, wondered if he was Eliseo Diego. He was then a venerable white beard unsuspectedly balding. His contemporaries seemed like younger brothers. It turned out the joke was on them as he didn’t get any older while others lost their freshness, hair, pounds, physical and/or mental agility and for a long time the tables have been turned. That, despite a copious medical record very well concealed.

With the bias of affection, there are those who say he’s the best poet in the world. There’s no need to exaggerate, although some verses are saved for posterity.

These fires feed this man who writes and writes on a battered computer with no more to give. Leaving poetry behind he is dedicated to finishing enormous drafts, novels that became priorities in the rush of life.

No one would expect that behind this thunderous voice asking who’s last in line at the farmer’s market, this competent cook who saves me from the daily doldrums, is this Amazing Poet in “atrocious invisibility” who tomorrow, June 9th, will be 80 years old.

8 June 2013

Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency Nullifies Dismissal of Actress Lynn Cruz

![]() 14ymedio, Havana, 21 May 2018 — Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency has ruled in favor of Lynn Cruz with regards to the claim presented by the actress after the Performing Arts Artistic Agency (Actuar) put an end to her contract last April without complying with the mandatory 30-day notice period. The artist was informed of the decision on Friday, 11 days after the five members of the court agreed with her.

14ymedio, Havana, 21 May 2018 — Cuba’s Labor Justice Agency has ruled in favor of Lynn Cruz with regards to the claim presented by the actress after the Performing Arts Artistic Agency (Actuar) put an end to her contract last April without complying with the mandatory 30-day notice period. The artist was informed of the decision on Friday, 11 days after the five members of the court agreed with her.

The document issued by the Labor Justice Agency specifies that there was a violation of Resolution 44 that regulates labor relations in organizations overseen by the Ministry of Culture.

For Lynn Cruz, this ruling makes clear that Jorge Luis Frías Armenteros, director of Actuar, violated article 297 of the penal code with the “unwarranted imposition of a disciplinary measure.” continue reading

The president of the Labor Justice Agency, Iván Rodríguez, told Cruz that after this ruling, “it did not make sense to go to the municipal court” because Actuar was going to continue to “represent her without problems.”

As of now, the actress could be hired again but after what happened she does not trust that she will be able to return to her work, because she believes that the agency can work behind her back to prevent her name from being chosen by a director who is interested in her work.

For Cruz, there is no way to repair the “psychological and moral damage” this measure has caused her, in addition to the “loss of work” she suffered in this case.

The actress also wonders if this step was taken to protect Frías, that is to avoid a criminal complaint. This Friday, when asking Ivan Rodriguez if the director of Actuar would be sanctioned for his error, the president of the Labor Justice entity replied that the agency “could not sanction its own director.”

“Evidently they are protecting Frías, the procedure he used in my case was clumsy since the contract was violated, but there is an intention to protect him after that blunder he committed,” Cruz believes. Cruz is of the opinion what was decisive in her case — unlike the cases of Ariel Ruiz Urquiola, Oscar Casanella or Yanelis Nuñez — was that she recorded the public hearing and “made the recording public,” a hearing in which the director acknowledged his error in not notifying her 30 days in advance before canceling the contract.

At the public hearing Frías said that Actuar’s decision to terminate her contract had been taken due to the actress’s “demonstrations on the internet” against “the main leaders” of the Party and the government and acknowledged that they had made a mistake” in the procedure.”

Lynn Cruz (born 1977) has developed her career between theater and cinema, although she has also participated in some television shows. She has worked on several Cuban films including Larga Distancia and La Pared.

Cruz has a special performance in the documentary Nadie, directed by Miguel Coyula, which includes testimonies of the poet Rafael Alcides, an intellectual censored on the island. This film was presented at the independent El Círculo gallery with the presence of Alcides himself, without major incidents. However, another presentation was repressed by State Security, which blocked public access.

_______________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.

Cuban Regime Frees Activist Lia Villares

Diario de Cuba, Havana, 23 December 2017 — Activist Lia Villares was released this Friday morning after being detained since Wednesday, activist Rosa María Payá Acevedo said in her Twitter account.

Diario de Cuba, Havana, 23 December 2017 — Activist Lia Villares was released this Friday morning after being detained since Wednesday, activist Rosa María Payá Acevedo said in her Twitter account.

Villares, in addition, was fined 500 pesos by the authorities, according to Martí Noticias.

During the arrest, “her interrogators told her that she had committed crimes, and in order to prove it to her they showed her a photograph that she had taken some time ago with two policemen. In the photo she appears with a fan with the logo of the CubaDecides opposition initiative” directed by Payá Acevedo, according to the Miami media. continue reading

In the cell where she was detained, the activist wrote with a stone on the wall “Art Yes, Censorship No. I am free.”

“They tell me that this is a damage to property and carries a fine of 500 pesos,” she explained.

Villares was arrested Wednesday along with other artists when they tried to attend the staging of the play Psychosis.

Among those arrested and then released were Tania Bruguera, actress Iris Ruiz (protagonist of the monologue that was to be performed), Adonis Milán (director of the play), poet Amauri Pacheco, art historian Yanelys Nuñez, another person identified as José Ernesto Alonso and the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara.

The plot of the piece revolves around a person enclosed in a very small space showing obvious signs of madness who wants to leave the place.

The version that was presented was inspired by the events of 2010 at the Psychiatric Hospital of Havana, popularly known as Mazorra, where 26 patients died of hunger and cold. In the monologue direct allusions were to be made to Raúl Castro and terms such as “dictatorship” were used.

The independent gallery El Círculo is subject to constant repression by the regime. State Security also closed this independent space in April to prevent the presentation of the documentary Nadie, by Miguel Coyula, which deals with the life of the poet Rafael Alcides.

Likewise, the political police set up another operation last November to prevent public attendance at the work “The Enemies of the People” directed by the documentary filmmaker Miguel Coyula, which fictionalized the final minutes of Fidel Castro.

Anime Animates Coyula / Regina Coyula

Jorge Enrique Lage interview with Miguel Coyula (fragments) 2

Miguel Coyula: [… the cinema where I first encountered anime.] [… like the video games of the late eighties and early nineties, the anime of that time had no big budgets for a fluid animation at twenty-four frames per second, Disney-style. Then they went to a visual design and assembly and sound very often shocking.] [… in the subconscious, that left a mark on the film I make.]

For me it is very important to work the space and design the storyboard to the last detail, so that no image is repeated during the editing of a scene. That is something that comes from anime, and the comic book in general. Each panel expresses an idea, just as in literature each sentence expresses something different.

As for video games, the animation was even more limited: 2D, but that same limitation …] [… it made me shape an aesthetic where the image is as loaded as possible with small elements that add density to the setting.

[… the anime stories often left me with a bitter taste. Yaltus, known as Baldios outside Cuba, was a film that marked me a lot. Its apocalyptic and depressing ending, where the earth is completely contaminated with radioactivity, left me in a state of discomfort that I have pursued in my films.

[… one of the most striking films for me, for the stylistic collage it represents, was Belladonna of Sadness, 1973. For some reason it’s the 70’s that keeps calling me over and over again as a source of inspiration.

Site Manager’s note: Once all the fragments of this interview are translated (by different volunteers) we will unite them in order, in a single post.

Counterrevolutionary or Communist / Regina Coyula

Sadly, the above video is not subtitled, but whether or not you understand the words, you can observe Miguel Coyula and Rafael Alcides speaking.

Jorge Enrique Lage interview with Miguel Coyula (fragments) 3

Miguel Coyula: … And it’s [Rafael] Alcides for several reasons. First, because in my opinion he is the best Cuban poet alive. Pata de palo, Agradecido como un perro and Nadie are indispensable books; Especially Nadie [No one], written and censored in 1970, and that doesn’t see the light until 1993, when I read it for the first time and it hits me.

Alcides is often described as a sensualist, but his range is very wide. Take, for example, his poem “El Extraño“, which appears in the film: it is very brief, stripped of artifice, combines the existential and the political in a universal way, with an admirable economy of means.

But even if Alcides had not been able to write anything …] [… his own person is poetry; he has the gift of speech, a diaphanous word, he speaks of beauty and poetry without intellectual poses, despises politicians and yet can speak of them with poetry, to the point that the passion of his gestures makes him a force which seems more typical of the field of fiction than of the documentary. continue reading

[… probably Alcides is one of the few Cuban intellectuals of his generation (in fact, the only one I know of) who, residing on the island, has no qualms or filters when it comes to making public what he thinks. He has paid the price for his honesty with ostracism. Also contradictions and guilt coexist in his person. He gave himself up to a dream, sacrificed himself for it and accepted failure. I’ve always been interested in misfits. Alcides contained all the elements that interest me in the construction of a character. Perhaps his honesty and his nonchalance mean that the film can not find a place anywhere: neither in the diaspora nor in the intellectuals of his generation who remained on the island.

The fact that the film is indistinctly labeled “counterrevolutionary” and “communist” is something I am very pleased about.

The first thing we recorded was a four-hour interview, from which came a short web mini-series, seven chapters, titled “Rafael Alcides.” (Many people believe they have seen Nadie but what they have seen is the miniseries on YouTube that only totals twenty-nine minutes).

At first there was no theme at all, it was about Alcides talking freely, but he himself was outlining the theme of the Revolution and then we began to record more specific questions.

Site Manager’s note: Once all the fragments of this interview are translated (by different volunteers) we will unite them in order, in a single post.