In March 1956, Alberto Bayo, who soon was to become a Cuban revolutionary commander, while training Castro’s little army in Mexico, wrote the first traceable record of Fideliterature, where Castro is compared with a “lighthouse than gleams airs of freedom”, and as one of our “great locos that pursue Glory to sow a beautiful fruit in History.”

Indeed, many charismatic leaders have been called “locos” by our national tradition, which despises common sense and praises maddened social actors, as much as it disregards conventionalism in order to foster improvisation.

Months later, Ernesto Ché Guevara himself depicted Fidel as a “blazing prophet of the dawn.” And then an avalanche of verses came pouring upon his epical guerrilla, from the Ecuadorian Elías Cedeño Jerves, who sees him as an eagle-in-chief flying over the mountains of Sierra Maestra (although those birds are inexistent on the Island), to Cuban Carilda Oliver Labra, who focuses her gratefulness to the “male groin” under Castro’s green-olive uniform (thus settling the basis for Latin American Machismo-Leninism). continue reading

Local Nicolas Guillen and Chilean Pablo Neruda, Pura del Prado (that was to become one of the most emblematic poets of Miami), Argentinean Julio Cortazar, and, of course, the rapport-reporter Herbert Matthews from the New York Times, who, as Anthony DePalma has revealed in a recent book, was “the man who invented Fidel” as a Western literary hero in a continent prone to Robin Hoods that could expiate the guilt of superiority of the United States.

The “farmer´s morning almond”, a “sun in every corner”, the “purest rose of the Caribbean” with his “warm forehead”, “thriving arms” and “sweet smile”, were among the miraculous metaphors of a time when kitsch was considered correct as long as the people could repeat it.

The Cuban troubadour Carlos Puebla sang contagiously that “fun is over, ‘cause commander is here to put a stop”, equating chaos and capitalism, while order and austerity were the new undeniable values. Puerto Rican singer Daniel Santos reached the climax with his guaracha: if Fidel is to be a communist, put my name on that list, for I do agree with him (just before fleeing from Cuba in the 1959 itself, as did many ephemeral enthusiastic whose artworks remained behind as incessant icons.

In the summer of 1961, with his Browning pistol resting like a peace-pipe on a table of the Cuban National Library, Fidel Castro himself had to frame the limits of our intellectual illusions: “Within the Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing”.

While abolishing fundamental freedoms, Fidel declared himself to be enemy of any cult to his own personality. Soviet-like monuments were carefully avoided, so we have little to say about fidelistics in Cuban statuary. But the cultural politics imposed socialist realism as the best approach to beauty. Many artists were censored for life, erased from dictionaries and catalogs. Castro as a literary character showed up here and there, in pamphlet paragraphs where he could be heard in the Revolution Square applauded by workers, or raising his machete in a sugarcane field.

One exemption is the deconstructive documentary “Coffea Arábiga”, filmed in 1968 by Nicolas Guillen Landrian, nephew of the Nicolas Guillen that was President of the Union of Writers. There, the image of an over-acting Fidel during a speech in Havana University Hill is followed by a soundtrack of the then forbidden Beatles: The Fool on the Hill, with captions emphasizing that he “sees the sun going down and the world spinning around.”

The bufo theatre was abolished very early, to assure no impersonations of a funny Fidel on stage, whose solemnness was consecrated by Article 144 of Cuban Criminal Law, which punishes with up to 3 years in jail the crime of “aggravated contempt” to his public figure.

Skipping over the seventies of obscene ostracism for all artists considered conflictive, and also over the centralized eighties and the balkanization of the nineties, we can concentrate in the Cuban representations of Fidel in the so-called years zero or 2000’s.

For example, Bernardo Navarro Tomás, now residing in New York, appropriates pop and retro banner design to re-narrate Fidel’s biographical milestones, where terror seems just a commercial masquerade.

Street artist Danilo Maldonado Machado, El Sexto, in Havana, bets on bad-painting with explosive collages and nightmarish splashes, including slogans in the lips of a Castro that reminds us of a Minotaur in his labyrinth. These dialogue boxes are his citizen response to decades of monologue with the trademark of Fidel. Just as his own skin is used now as a dissident canvas tattooed with two recent martyrs of Cuban civil society: Laura Pollán and Oswaldo Payá.

Yanoski Mora became famous when he was arrested for selling to tourists a portrait of Fidel crowned with feathers like a Native American chief, a reproduction of a photo of Castro in 1959 with Oklahoma Creek Indians. He later refused to be interviewed or show his oil original. He had learned this esthetics lesson from the political police: the international left is allowed to depict Castro’s decadence (for example, Ecuadorian Oswaldo Guayasamín), but Cubans should not cope with His Holy Image, unless it is to portray the virtues of the retired leader.

A painter awarded the National Visual Arts Prize, Pedro Pablo Oliva, created oneiric landscapes where “Big Grandpa” leads smiling crowds that question themselves through text-boxes. Despite his international prestige, this exhibition of Oliva was doomed to take place only in his private studio in Pinar del Rio province, under the close surveillance of the authorities.

Anyway, during the 10th Biennial for Visual Arts 2009, the exhibit State of Exception included the installation of a carnival machine designed by Nancy Martínez: “A sequence of one,” which offered to winning players a series of plush dolls of Fidel Castro, from the young warrior to the convalescent old man.

The hinge between visual arts and writing came in the extreme style of Juan Abreu, exiled in Barcelona, who is updating in his website the evolution of a mural called “El super-ensartaje” (super-threading), where the historic alpha-males of Cuban Revolution are exposed in a homo-pornographic orgy. The complementary literary aggression is a trilogy, where the mummy of LoverCommander, toppled by a Coup de Etat, is exhibited in a cage, kept alive by drugs and condemned to listen for eternity the marathon of his own speeches, being fornicated by a character that travels from the future only to satisfy his Fidelist fantasy.

Not far from the Revolution Square, where he lives, Jorge Enrique Lage, as part of the fiction writers of Generation Year Zero, has turned Fidel into a Superhero with many Hollywood tics, in his short-story for the anthology “Cuba in Splinters” by O/R Books, New York 2014. Fidel, as a character by Argentinean Jorge Luis Borges, discovers the power of freezing time. He can now wander free of security and wonder what kind of country he has really created, in intense instants for reflection upon his long-lasting loneliness in power.

In the independent digital magazine The Revolution Evening Post, episode 4, in a list of 21 points to approach a 21st-century literature on the Island, the first provocation deals with the figure of Fidel, or rather with his abnormal absence in a context with a well-established genre of the Latin American Dictator Novel, from the times of “Facundo” in 1845, to “Mister President” and “The Great Burundún Burundá is Dead”, to “I, the Supreme” and “The Autumn of the Patriarch”, to “The Perón Novel” and “The Feast of the Goat” a decade ago. The Cuban exemption could be “Reasons of State” by Alejo Carpentier in 1974, where he prefers to caricature a collage of foreign dictators, to avoid suspicions from the active readers of Castro’s State Security.

At least three other writers of Generation Year Zero push the limits of Castro’s world as will and representation.

Jorge Alberto Aguiar Diaz in “Fefita and the Berlin Wall,” explores two desperate lovers that cloister themselves out of a country devoured by crisis. Fidel follows their acts as an unavoidable voice in every TV set of a city in ruins, inhabited ruins that in his novel “The Surveilled Party” Antonio Jose Ponte believes resemble the body of the premier, and moreover, that they were artificially imposed by him to resemble in turn the promised US invasion that never was.

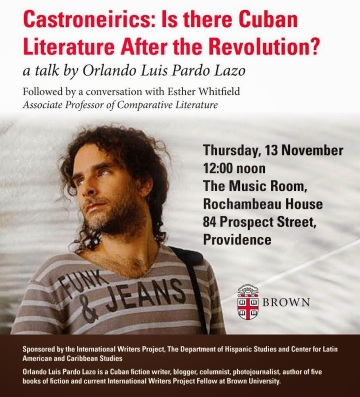

In my novel in progress “Alaska”, on which I work as a Visiting Fellow of the International Writers Project, fiction is understood as filling in the gaps of crucial pacts where Fidel Castro and other political, entrepreneurial, exiled and religious elites become criminal complicit of contemporary historical deeds.

Ahmel Echevarría in his censored novel “Training Days”, later published in Prague, uses a Fidel-like homeless person as witness of a funeral procession at Revolution Square. This old and shrewd urban prowler has wanted all of his life to be a writer, and even dares to give a lot of advice to the narrator named after Ahmel, denoting a Lucifer-like lucidity: Fidel as a fatuous Faust. It was Gabriel Garcia Marquez who stated that his friend Fidel was an extraordinary writer, but without the chance ever to write, given his many official duties. Dreams are the remaining realm of former revolutionaries. Guillermo Rosales, a 1993 suicide that destroyed most of his novels, in “Boarding Home” boasts of being an “absolute exile”, only to succumb every night to the nightmares of Castroism. His self-referential protagonist cannot get rid of the oneiric omniscient omnipresence of Fidel. The author himself is a kind of schizoid Fidel. His mental disease has literally and literarily immortalized Fidel, to the point that the director of the Cuban Book Institute recognized in private that “as long as those dreams remain in the book, it can never be published while Fidel lives”.

In the late 80’s, Heberto Padilla and Reinaldo Arenas came upon the same image in their novels “Heroes Are Grazing in My Garden” and “The Color of Summer”, respectively: to contemplate their lost homeland from the air, flying in a helicopter with Fidel Castro, who keeps describing the reality below only to please himself.

Arenas’ trip is a sarcastic series of bloody events that barely hide Castro’s homosexuality: as in Juan Abreu’s Super-Threading. On the contrary, the flight of Padilla embodies the Oedipus complex that Cuban intellectuals suffer since 1961, when a despotic pistol incriminated them for being so complaining and so little committed to the social process.

A similar edipic syndrome drove Norberto Fuentes, a former militiaman and secret agent of the Cuban Ministry of the Interior, now exiled in USA, to write in advance “The Autobiography of Fidel Castro”, in an interpretation of the personality of a man “much more intelligent” than his auto-biographer and former ex collaborator, and to whom the author renders his bitter-sweet admiration, verging in an unconfessed homoerotism towards the patriarch.

In this trend we can classify most books of Fidel’s defectors, although they are not fiction in principle, but it’s obvious their efforts —generally failed— to restore a certain human condition to the myth: a hitman like Jorge Masetti in “Furor and delirium”, a foreign diplomat like Jorge Edwards in “Persona non grata”, Cuban scientists like Hilda Molina in “My Truth” (2010) and Armando Rodríguez in “The robots of Fidel Castro” (2011), and even his personal bodyguards like Juan Reinaldo Sánchez in “The hidden life of Fidel Castro” (2014).

And this remits to the women that loved Fidel and decades later decided to tell it, as in “Havana Dreams: A Story of a Cuban Family,” by the actress Naty Revuelta, who was his adulterous lover and mother of a girl named not Castro but Fernández who, when grown-up, fled disguised from Cuba only to predictably write “Castro’s Daughter”. Just as his exiled sister Juanita Castro released “Fidel and Raul, my brothers,” in a delayed 2009. The most passionate of the —let’s say— bed-sellers is “Dear Fidel” by German-American Marita Lorenz, who claims to have been drugged and forced to abort by Cuban State Security, and yet she returned as a CIA agent to poison Fidel, only for him to discover the plot and fetch her his Browning with this challenge: it’s loaded, shoot me, I won’t die, no one can kill me, I’m immortal (a startling spell that has lasted for over 55 years now).

Cuban novelist Zoé Valdés, sent to Paris in diplomatic mission, where she defected in the early 90s, deals in a prosaic way with Castro, making a cartoon out of his character and calling him Super-XL Size, according to the dimensions of his —you guess what— testicles. Furthermore, her compilation of political articles could not avoid a Castrocentric vision, even to criticize his communist dictatorship to its last foundations: so “The Fiction Fidel” was her choice for a title.

In fact, pornopolitics seems to be our artistic reaction to the sequestering of the Cuban body within the homogeneous masses in front of the uniformed unique leader. No places for pleasure are legal on the Island since 1959. And while many were being stigmatized and even expelled from their jobs for hiding a lascivious paper or a hot hard drive, Fidel could afford a 1-week 7-page interview with Playboy, and return reinforced in his convictions to persecute capitalist degradation in our people.

Wendy Guerra, in her novel “I Was Never A First Lady” appeals to the nostalgia of her demented mother to recover the merciful monstrosity of the Number One Man in the golden years of the Revolution, a system devoid of first ladies since the revolution itself was the eternally virgin bride. Then, she also explores the first days without Fidel, when an emergency surgery almost kills him in July 2006. Wendy Guerra seizes the sinister silence or the deadly deafness of those meaningful minutes that opened the post-Castrozoic Era in Havana, while Miami yelled with histrionic hysteria.

In many ways Fidel seemed shielded by women’s wombs. The poet Reina María Rodríguez, in her now disregarded unconfessed crush on Castro, made it clear: “There is only one way to care about him. We have grown up beside him as if he were a tall tree”. No wonder why the official propaganda compares him to a centenary Caguairán tree, as his health looks more and more deteriorated in each sporadic appearance —or apparition— in national TV.

About his magnicide on the Island (quite common in a number of foreign best-sellers and videogames) the dystopia in progress “Alter Cuba” by Raul Aguiar is so far the best effort to reshape a Planet Cuba where Castro vanishes from our history before leaving a noticeable trace. About filming a fictitious Fidel, only in 2008 the local movie “Kangamba” timidly showed his shoulders with their emblematic epaulet. And then in “Memories of Overdevelopment” by Miguel Coyula, we have him all over as pop reference and reincarnated in a stout walking stick called Fiddle, which is humble enough as to dialogue after half a century of monologue.

When Soviet communism collapsed, the Cuban troubadour Pedro Luis Ferrer released a series of songs full of good humor that provoked the anger of the censors. One of them reminds of the “Big Grandpa” paintings of Pedro Pablo Oliva, since it’s called precisely “Grandpa Paco”: “grandpa built our house with lots of sacrifice, but the least move now needs his approval, as grandpa still keeps his old weapons ready to make himself obeyed”. The apotheosis was the underground punk band from Havana, Porno Para Ricardo. Paying the price of going to jail more than once, their front man Gorky composed the paroxysmal provocation called “Commander”, where he offensively mocks Grandpa —again from politics to pornophilia— whose official newspaper by the way has been called Granma from the beginning.

Once the fear of fictionalizing Fidel is over, I’m afraid that it will be too late for a fiction to be fully meaningful about him. Besides, it’s more than likely that Cuban literature as such will find itself in difficulties to be appreciated beyond the straitjackets of socialism or its symbolic undermining. Both market avidity abroad and the lack of local readers will pose a formidable barrier to avoid any experimental estrangements and thus to remain stuck to the stereotypes of what Cuban writing and arts in general should look like.

As politics was too important to be left in the hands of politicians, literature was too important to be left in the hands of intellectuals. Fidel Castro managed to impose himself for too long as a non-fictionalizable figure. Being an incontinent narrator himself, competence was considered contempt. It might be time to turn the F chapter of Cuban literature and delicately recognize our defeat. Unless, of course, some authors are willing to grab that Browning back from the summer of 1961 in the National Library, and make a statement that escapes the reactionary rationale of within/against/outside the Revolution.

[Original in English]

13 November 2014