Regina Anavy: I understand you are here on a special two-year grant from ICORN [International Cities of Refuge Network].

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo: Yes. ICORN is an NGO based in Norway. They make contact with city governments. They believe that working with cities is better than working with countries. Maybe there is a conflictive immigration policy, but the cities are happy to have you. So in Europe they have dozens of cities, and I think in America now Pittsburgh is becoming an ICORN city and maybe Las Vegas. But after a year [in Iceland], I will be going back to the U.S., to enter a Ph.D. program in comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

OLPL: Mainly I will be a teaching assistant in the second year. continue reading

RA: Will you be teaching comparative literature in Spanish?

OLPL: I don’t know yet. I guess in both English and Spanish.

RA: Is that a five-year commitment?

OLPL: It could be up to five years to get a Ph.D. in comparative literature. It’s a special track, like a pilot program. It’s called “International Writers Track,” and writers are invited to the department. They know that we are not academics; maybe we don’t work or think as an academic, but somehow the purpose is to give us tools to understand the codes of literary criticism or academic essay. I write literary criticism, but it’s not with literary rigor; it’s my impressions. So it could be very interesting.

RA: So that will give you a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature?

OLPL: If I manage to get through to the end. There are several universities there; this is the one they call “Wash U” because it’s Washington University. I was there for a conference in January 2015. It was like a marathon. I went to an event for human rights in Chicago. There was a lady there, a professor from Poland, who had been following Cuban affairs, so when she found me on Facebook, she told me, “You need to come here. It’s a one-hour flight, and we will pay for you to go back to Brown University” [in 2015, OLPD was an Adjunct Professor of Creative Writing at Brown University]. I went there for a couple of talks, and she asked me about my future, and somehow she had the impression that my future was lost because I was not an American, and she said, “Maybe we can help you here. There is a new initiative going on.”

Finally they nominated me. I didn’t apply for this Ph.D. I mean I sent the documentation but only after I was nominated. Other universities had shown interest, but always you need to start by the phone consult, then the GRI test for mathematics, and maybe somebody assesses you there. But this process circumvented all that, and they were very kind.

They understood that I was here [in Iceland], so there is already one year deferred [for the Ph.D. program]. This is why I cannot defer any longer. So everything came together for Reykjavic and St. Louis, and I was “lost” but then suddenly had two options. I was able to manage, talking openly, to both parties. “I have this option, can I do this? Maybe not for two years, maybe for one; now’s the time to go there [Wash U.] and be a good student after being a bad boy.” I think I will be able to keep on with creative ideas for both these options and at the same time add some discipline, and the writing will be good.

The Future Of Cuba

OLPL: You know I was in Arizona, in April, at the Sedona Forum, with John McCain and the Director of National Security. I saw that they were mainly politicians, people with different positions regarding Cuba, people who have been traveling to Cuba. Usually you talk in front of human rights people who agree with you in a way, but these were people who can really change things.

I was happy to talk there on a panel with plenty of dissidents, and there were Russian dissidents and the realities were terrible, really terrible, and I was somehow trying to put some ideas into this “new cake” about Cuba and how it is not about the embargo but to make sure that we are moving into freedoms in one way or another, not just trying to make money, or like China – the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Are we moving into that or are we making sure from the beginning ….?

RA: Well, that’s what it should be, the human rights situation.

OLPL: Sometimes I become really skeptical and sometimes I push very hard.

RA: Because it’s all about business. It’s all about making money. And “Oh, the Cubans can be entrepreneurs now.” Yes, as long as the Government lets them. It could be taken away tomorrow. There’s no law.

OLPL: The legal space is very limited. Technically, you are not even an owner of your business. You have a license, and you pay a tax. But it doesn’t give you any judicial personality. You’re not registered as a trademark; you don’t have a lawyer for your business, and basically you have no rights. So you are a citizen, who maybe is making a lot of money now, because paladares [private restaurants] in Cuba are making a lot of money, but money is not [the same thing as] rights, and this is why when they close a paladar, nothing happens. Nothing. You’re not a person. But, anyway, it’s a process that is starting now.

RA: The other thing is that the money you earn in Cuba – where do you spend it? It all goes back to the Regime.

OLPL: All of it. You know, even remittances. We all need to help our relatives. We are talking of billions a year.

RA: I know. It’s one of the main things keeping the Government going.

OLPL: What is the option? There is no boycott.

RA: Are there other Cubans here besides you?

OLPL: Yes. That’s another story. The island has been conquered, completely conquered. Maybe there are over 50. I haven’t met them all, but there are stories, and, of course, not all of them are good stories about Cubans here. Legal troubles, violent troubles, our fellow countrymen. But I have met two or three families; some of them have family in Cuba. So there are beautiful stories. There is a young girl here who just had a baby, and she lived 50 meters from my place in Havana. I haven’t met her but my mother knows the family.

RA: How is your mother doing?

OLPL: She’s eager that I return to America so she can visit again, because she came once last year. She has a visa now. It’s a multiple entry visa, so she only needs to buy a plane ticket. Now it seems that shortly she will be able to buy one on American Airlines, maybe for $200. Because the prices are going down; capitalism is bringing down the prices.

RA: Did you request asylum in the U.S.?

OLPL: A green card. Let me mention something about that. The word “asylum” – I have entered America twice, since I left, before the six months, to keep the green card active, and also I have a reentry permit. It’s like a passport for non-U.S. citizens, that allows you to stay even up to a year, but I have been reentering every six months, less than six months, to avoid the bureaucracy.

And both times, it happens sometimes to residents, you are stopped; you are asked more questions. It seems when I show the reentry permit there is no problem, but suddenly something happens. Immediately they come and say, “Come with me, please.” I go to a room. That’s what I’m curious about. They ask no questions. They type all my information again.

I’m almost sure it is very governmental, like tracking a possible political activist, and then once, more than two times, there was a young girl there, a young officer. And I was trying to be gentle with her; it was a little like Cuba, and then I said to her, “May I do anything here while I am in America, because I will be reentering the country several times? Maybe I can save your time; you can save my time, if a document is missing…”

“No, no, no, no, no.” Very Latin, maybe she was telling me a little more than what she had to tell me. “It’s very likely that you will be stopped every time you reenter, but there is no reason; there is no problem, and that’s okay. Because you are a political refugee, no?” I said, “No, not at all.” But that was a bit of information. I am a normal cubanito. I didn’t know what to say so, I just said, “No, no, no, I’m a resident.” I was surprised, and maybe there is some kind of…”

RA: They’ve flagged you.

OLPL: Yes, like “This is a trouble-maker…”

RA: But why don’t you just get in and…?

OLPL: Maybe. But it was not about that. When I was in America, I obtained my residency in 2015.

RA: So you’re a resident.

OLPL: Yes I am. I have a green card. I’m not requesting…

RA: But you don’t want to become a citizen?

OLPL: I cannot do it until 2018. So Cuba will change; I will change. America will change. I don’t know exactly how. I haven’t made up my mind.

RA: Do you think Cuba’s going to change enough by 2018 that you would want to go back?

OLPL: I don’t know.

RA: I doubt it, frankly.

OLPL: Yes, but there is always a biological solution.

RA: Even so, they’re still going to be in charge.

OLPL: I know, I know. It depends also on – I mean, I have been looking for a kind of empowerment, I hate the word because it’s been used now to empower society, but, let’s say I am trying to position myself, not only as a Cuban blogger or dissident, but as something else. Let’s say I’m waiting for a book to be published or to be well-known, maybe something like a Ph.D. or this fellowship for a Ph.D. scholarship, something that makes my name known – a prize, a literary honor, so that when I decide to return, their lowest price is to ban me from reentering, but if they allow me to reenter and harass or detain me, that will have a high political cost for them.

So I am trying. I don’t know how exactly – but in my mind, the scenario is that I think Cuba is not likely to be democratic in two or three years, but I am thinking that the political cost will be high, and then I will be willing to do it, to get a ticket and be stopped. I can even do it without an entry permit. I have a passport, and my passport is good for the next four years.

RA: But you have to keep renewing it.

OLPL: Renewing is like a stamp. Not a passport, I mean. You understand that the expiration in my passport is 2020. But what they call renewal is like a stamp that you pay for, a visa for two years. I need a visa for my country with a valid passport. But even that – I can apply for it, but I am afraid that – another consideration is that you need to deliver the passport.

And Tania Bruguera [Cuban installation and performance artist] three years ago delivered her passport, and they kept it for one year before she could travel to Cuba. So when they gave the passport to her, somehow they felt, “Now you are tamed. You are low profile.” But she was one year without a passport. So I maybe need to go without any stamp and be stopped like that and show the Americans in line, or maybe they will allow me to enter. And then I will be safe from Cuba. If I can do it, every Cuban can do it.

Reykjavic

RA: Is there a Cuban Consulate in Reykjavic?

OLPL: Fortunately, not. I feel very, very, very happy. First of all, I met Cubans here, including the one who created a group Cubano Islandia. When the Ambassador comes from Cuba on holidays to visit beautiful Iceland, they prepare dinner. And one of the girls here, in one of my talks at the University of Reykjavic, was very critical. At the end she said, in English, “Okay, I know very well what I am talking about, because I am Cuban!”

When I am in public I’m not completely truthful, because somehow I know this is all about the repercussions – there were many professors there – and I said, “I’m so happy to find you, another Cuban. I wish that we could have this talk at Havana University. For five years I haven’t been invited; I haven’t been published, and you were not claiming for that right of a Cuban. We can have this conversation here, with all that anger; we can quarrel here and then shake hands and go back to our places. And nothing happens. There are no political police out there.”

So that was my answer, because you are talking in English in Iceland, and I really was surprised when she said, “I’m Cuban!” Oh my god, like “I’m Cuban, too!” And then some other friends told me that she had been organizing a dinner with the Ambassador. Everybody wants to be on good terms with the Cuban authorities.

RA: Oh, I think you gave that up a long time ago. Have there been any repercussions for your mother?

OLPL: No. Around the first year, maybe when I was making the decision to finally stay, they went to my neighborhood, to the block. They interviewed several neighbors but not my mother, of course, but my mother knew. “Maria, what’s going on with Orlandito? Something happened.” And my mother was very nervous that day, and they even pressured the young man and my friends who took me to the airport in 2013, to see if he was illegally renting the car. So it was this kind of stupid pressure; I don’t know what the purpose was.

RA: To scare them.

OLPL: And that was a tough conversation that I had with my mother, because when she called, very nervous – maybe that time they were listening – and I said very strongly, “Even if somebody shows you a piece of paper saying Orlando is dead, you don’t believe it, because you are in the hands of Evil. Where they print fake newspapers, where they talk to fake friends.“ I was very strong, and somehow she was more encouraged.

“So you say, ‘If he’s dead, he’s in the hands of God. I don’t care about any information from the Cuban Government.’ like that: ‘No, thank you!’ “ Because she was saying, “Something must have happened to you because they’re here asking.” After that, she was happy to be in America. I took her to conferences, and she was very happy to see a good environment and good people.

RA: Does she understand English?

OLPL: Very little. But at the end she was talking in the supermarket. She likes to buy stuff, food and things, and she was asking for something, and I was buying something else, and she went to a girl and said, “I want rice, white rice.” So she was getting more courageous. She doesn’t know anything, no, but she knows the word “rice,” and she said, “I want rice.” So when it comes to buying food, she was able to use English.

RA: Is there a large arts community here in Reykjavic?

OLPL: Yes, of course. And I would say everybody writes; this is crazy. Poetry, chess, readings.

RA: Are you learning Icelandic?

OLPL: Very little. I was trying to learn more but my time…. I mean, to read 10 hours a day and translate for a course I was taking, and then I said, well, I will not have one year of scholarship, I will have half a year, because I was putting a lot of energy into that, and then I quit. Maybe if I knew that I was going to be here for two years I would make an effort.

RA: It seems like it would be a difficult language to learn.

OLPL: Once you get the rudiments and you know the codes, you understand what is a verb and what is a noun. And then at some point you can incorporate new words very easily. At least I bring them from English, a lot of words. And even they don’t look like language. Many words, on the highway, the signs, because the bridges are only one-way. I don’t know the origin, the etymology.

RA: But you play with language anyway. That’s one of the things you like to do.

OLPL: Yes, I like to do that.

RA: You’re very good at making up words.

OLPL: Maybe in five years I can come here and work on a farm and teach Spanish. I wouldn’t mind being more like a hermit. Once having positioned myself in the literary field as an academic, or maybe publishing my novel that I’m finishing here, I will be more secure, and I wouldn’t mind being here for one year helping on a farm, making a little money. It would be like a spiritual experience, really, living with the landscape, but in a more permanent way than now.

RA: With this fellowship you have now, from ICORN, don’t you have to teach?

OLPL: No.

RA: Do you have to produce a certain amount of work?

OLPL: The “certain amount of work” can be one word. The application deals with reference letters and why you cannot do your work in your own country. So it is also a human rights organization. ICORN had a Congress in Paris in March this year. Some cities seem very active and push the writer to participate, but here, at the beginning, they told me, “No, you can be quiet.” I have been traveling in Europe because I have arranged that myself, but mainly I am forgotten here. They tell me, “Anything that happens, you call us; we can help.” They gave me some cards to go free to cultural centers, not all of them, but the ones that belong to the City Hall. They facilitate things here.

But I can be here for two years, and they will not be asking me to formally deliver 50 pages, even if it’s been written before. So it’s really a space and also a responsibility, because you are taking the place of someone else, and it’s a privilege. So it’s a good opportunity to move forward, even if I know that at the beginning I will be a little depressed, to be again in a city, surrounded by deadlines and people, but so far I have liked the people I have met here, and there are many reasons to remain.

RA: Is it easy to meet the local people here?

OLPL: Yes. They have a different code, but Reykjavic is really like a small city. So they are very willing to help with anything. At the same time they set limits. They help you and at the same time they say, “Okay, now it’s time to go.”

RA: Did ICORN help you find a place to live?

OLPL: No; it was granted to me. The house belongs to the City Hall. I like the place; it’s very nice. It has one room, a living room, a dining room, a kitchen and a bathroom, just in front of the City Hall.

The New Book

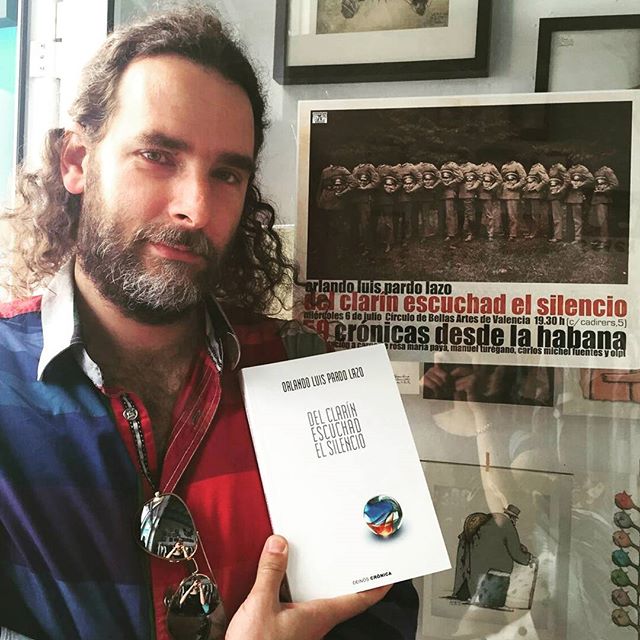

RA: I know you’re leaving for Spain soon to do presentations for your new book.

OLPL: Yes, Del clairín escuchad el silencio, a book of chronicles, some of my writings, my blog writing during the last five years. All of them have been published, but I rewrote every poem. I haven’t seen the book yet, because it’s very expensive to buy it and ship it to Iceland. The book costs $15 on Amazon, and then [I would] pay $30 for shipping [to Europe]. So I’ve decided to wait, but I’m very eager. I want the book.

RA: Can you buy it digitally?

OLPL: Not yet, but I want to talk to the publisher about that. It’s a very small publisher. Believe it or not, I had to buy a number of books. I managed to arrange four presentations in Spain. The publisher is Print on Demand. I said, “Maybe very few people will show up.” They said, “No, it’s vacation, maybe we can get 20 people there, maybe 30, 40.” I don’t know. But we can run out of books. This is very Cuban. So, I bought more books with my savings and forwarded them to the publisher, and those are my books, and so now I have now a packet of books that I will be moving from city to city.

RA: When are you leaving for Spain?

OLPL: Midnight. Tonight. And I will also be in London at the end of this trip, because there is a literary magazine, Litro, that is publishing a dossier of Cuban literature, and they included me. So I am little by little trying to regain the literary spaces that I lost because of politics and my blog. There is a short story by me, a very political story, fiction, and the magazine includes writers from outside and inside the island.

RA: Are you in touch with writers in Cuba?

OLPL: Many of them.

RA: I read Cuba in Splinters. Were those writers all from the island?

OLPL: There are three living mainly abroad. As time flows, that’s one of the things you can plot. You have this center of points within the island, and as time flows, they are scattered, you know? It’s a tendency, no?

RA: You write poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and you do photography.

OLPL: What I feel like writing is fiction, even if it looks like nonfiction. But I also like to write chronicles. Maybe sometimes I like to fictionalize them, or put some opinions there within the chronicle, so they are not pure chronicles.

RA: By “chronicles” you mean novels?

OLPL: No. Chronicles are like a journalistic genre, which is that you write a story, but it should be 100 percent true. I also write here and there some poetry but it’s mainly not really poetry, more like short stories, very small short stories, very narrative, but I don’t take an exalted or high tone. I do not pretend to become lyrical or create a poetic image; I try to be narrative. But the beauty is that it’s short, very well-selected and sometimes has contradictory points between the persons, and that creates an atmosphere of surprise or something that is a little unique like, what’s going on with this voice? It’s a little crazy.

RA: You’ve been compared to Cabrera Infante.

OLPL: I hope so! You know there is a tradition of Baroque writing with masters like Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Alejo Carpentier and José Lezama Lima. After them, together with them but not so well known as the Baroque writers because he wrote many things, Reinaldo Arenas, because with his novel, El mundo alucinante, The Delirious World, he mastered language. He was a guajirito, a country boy, who came to Havana, writing with grammatical and orthographic mistakes, and he wrote many things. He wrote poetry, theater; his first novels were very Baroque, and he’s part of that tradition.

So somehow my tradition is closer to those writers than to other writers that I also love, more realistic ones. So who knows? You start by imitation, by imitating what you love, and maybe little by little I will find a different point. But they used to tell me, when they wanted to criticize me, provoke me or make me nervous, “He’s like Guillermo Cabrera Infante without the talent of Guillermo Cabrera Infante.” I say, “Of course not!” What else can you say? Don’t compare me to Cabrera Infante.

RA: It’s because of the word play, the way you make up words.

OLPL: Yes, of course. Sometimes it’s anonymous commentary, but sometimes I receive that reference from writers in Cuba, who are not friends, and then I say in my mind, Yes. But when Cabrera Infante was alive, and that was until 2005, the Master was not published in Cuba. You were not defending your Master. So it’s better not to have the talent. Because if you have the talent and you are Cabrera Infante, you are talking about him now that he’s been dead for 10 years. And that’s hypocrisy. Forty years without being published in Cuba, and he’s not a genius, he’s a gusano [literally, a “worm,” what the regime called Cubans who left). He was very hated by the officials In Cuba because he was a great intellectual.

RA: I hear you have an article coming out in Smithsonian magazine.

OLPL: This is a story of the famous photo of Ché Guevara and what Ché Guevara means for Cuba. He’s become a symbol for everything, and if you go to Havana you have to take a picture with the photo in front of the Ministry of the Interior, like Obama did with a selfie. But I also tell the story of the photo, and I had to find some information about it, crazy things that happened. How Dr. Korda was not paid during decades for the photo – he managed to get some money at the end – and also about the discovery of the photo. The photo of Ché Guevara is a beautiful image, but it also represents violence and hatred.

The Exile Cuban Literary Movement

RA: How do you feel about being part of the exile Cuban literary movement? What does this mean to you?

OLPL: The last five years in Cuba, I was feeling completely exiled, and, consequently, I was feeling completely and dangerously free. It’s not only about courage, that we were brave. We were really scared of everything. But suddenly, as I started to be censored, not publishing any more with the publishing houses in Cuba, not being invited any more to publish in magazines or to be part of a literary jury, I realized that they couldn’t take anything else away from me.

And then I discovered my blog, which was like a bottle tossed into the sea, and I thought, they’re not going to read this, and I could be as provocative as I wanted, and people would be reading me. I love to be the center of events, but there is no Internet in Cuba. They [State Security] will not be reading the blog. But I got into more trouble because of the blog, thanks to the visibility that civil society and the blogosphere was having, thanks to Yoani Sánchez, so suddenly I found myself writing like an exile and living like an exile.

All my money came from donations or publications that I published abroad, 100 dollars that could last for three months. So my life depended on email, in a country without the Internet. I was trying to find a pirate connection, trying to go to hotels. I was trained to be part of an exile literary writing.

When I came outside I stayed for three years. It was not the original plan. So I have been lucky enough to organize and recover a sense of belonging that I didn’t have in Cuba. The anthology, Generation Zero, certainly needed the distance from myself in order to make the contacts, to push, to sell the story of a non-political generation to an editor in New York. It now has been published as Cuba: Année Zero in Paris, and it’s going to be published in German.

RA: Is any of your work getting into Cuba?

OLPL: Maybe. I tried to publish an anthology in Cuba, and they told me that the publishing houses were not publishing “group aesthetics.” If I wanted to organize an anthology it could be an anthology of new writers, but in many ways these anthologies, Generation Zero and Cuba in Splinters are ghettos, barricados. It’s a place were we are not censoring anyone. We are declaring ourselves and taking a position, and it’s allowed to make war against the Castros, literary war, and so this kind of political literary movement in Cuban cultural fields is not possible.

Now I have been feeling I belong and am able to help my friends and be part of this literary phenomenon much more than when I was inside the island. And besides, when I was inside the island – and this is sad – many writers somehow were considering me a political activist. I mean, State Security declares me a dissident and oppresses me, and my friends know that I am a writer.

I was even a member of the Union of Writers. Instead of saying, “Well, Orlando, I don’t know what you’re doing about politics, but I consider you a writer.” No. They are subdued by the narrative of the State that said I was a dissident, so I was feeling less close and had some hard feelings against writers when I was on the island, and now, from outside, everything goes better with those writers, because they feel safe from me, and on my side I can promote their works – not only the ones in the anthology but other writers.

RA: But can they read you in Cuba?

OLPL: No. It’s difficult. I have been sending the anthology with some of them when they travel, but it’s very limited. With this new book that I have just published, I am very proud. I think it’s our little baby, and it is not only my book but also the book of the blog, so it belongs to all of us, including translators, although it is in Spanish.

Many of these columns are already translated, and this book, although it’s not being commercialized digitally on Amazon, is going to be sent, free of course, to other contacts, including NeoClub Press and Hablemos Press. It’s going to be distributed in Cuba. So it’s a way of putting together my blog, with a cover, with my picture, and distributing it. My expectations are to re-conquer the island, and more than that: My plans are to be born again in Cuba in 2016.

There is a short story of mine in Litro, the literary magazine that is going to be published in London, together with some short stories of writers in Cuba, so when these writers take the literary magazine back to Cuba, they are taking my story there. So I am trying to recover a space that was a little lost and revive my narrative and my way of expressing myself, and my impact or influence. I want to do it again. I disappear for two years, a couple of years. Now I’m back. That’s the headline: He’s back!

RA: So the UNEAC writers will accept you?

OLPL: No, no, no. But that’s good. Let them be in conflict with me. Let Omar Pérez, a poet, take the magazine back. “Why is Orlando in here?” Why? Because he writes here; he belongs here. So it’s a movement. I’m dealing with a feeling of nostalgia, with pain and the feeling of loss. I do not project that, but it’s there. It’s a way of easing, soothing, like an act of a baby with a knife in my hand. I’m writing, I’m cutting people and cutting narrative….

RA: With a pen!

OLPL: Yes, a pen, but a penknife, with ink. So it’s dangerous. Beware: It’s dangerous. Not like the pen of an angel or a bird. It’s the pen of a bird, but with a sharp beak, ready to be a dart at some point. So I’m back. Not an angelic return. It’s like a devilish return, in a literary sense.

The Work In Progress

OLPL: By the way, I have been finishing my novel here.

RA: Yes, tell me about your novel.

OLPL: It’s going to be brief, because I believe in brief form – the post, the blog. I don’t believe in a big work. It’s about me, very biographical. I don’t believe now in the construction of characters. I don’t know what I’m going to do in the Ph.D., but I don’t believe so much in the construction of characters in literary procedure. I believe in writing about myself, even when I fictionalize myself, so it’s not biographical in a way.

I’m talking about Fidel Castro; I’m talking about Oswaldo Payá; and there are very delicate scenes there because I am narrating what happened to Oswaldo Payá. Of course I don’t know what happened. But I was at the funeral, and the novel moves from that point. I was there, and I approached the coffin only very late at night, not at the moment of mourning and giving condolences. I didn’t approach the family. At midnight, I approached his coffin, and the moment I looked at him, he started to bleed.

RA: It was an open coffin?

OLPL: You could see through the glass. And so the moment I approached at midnight, the church was empty. The next day everyone went back and the Cardinal gave a mass; so this was like a very personal moment. I was almost sure before Rosa Maria [Oswaldo Payá’s daughter] said anything. I was almost sure that certain things had happened to that man. I didn’t know what.

And then at the moment I approached, he started to bleed, red. From here, from the left of his face. And I understood that as a sign saying that something unfair, something unjust has happened. I don’t know what it is. I don’t believe in anything supernatural, but something has happened, and I can see here the traces of violence.

So it starts from there. I am trying to project the vision that if a man was killed, then a man killed him. And the man that killed him may be alive or not and is a Cuban or a foreigner.

So there is a certain issue that goes into the novel, and then the novel moves, and I move with the novel: Miami, New York, and it will end in Reykjavic. So I want it to be like a large chronicle. It was going to be entitled Alaska but now it’s not going to be like that. I don’t know exactly. I was thinking of using one Icelandic letter. Guillermo Cabrera Infante entitled once of his books “O,” only “O,” and I was thinking to use the thorn, which is a letter. It’s unpronounceable in Cuban. It’s a runic sign; it’s not commercial.

It’s almost finished. But I don’t understand the ending. I don’t know what the ending is. Or maybe the point is that there is no ending. It’s a fragment, because it’s not a thesis. Because I’m saying that I don’t know what happened. I don’t know, but it’s in my heart. So maybe I can just make the opening and the ending more diffuse. This is one chapter of 200 pages, of a novel that will never be written.

Aesthetically I’m interested in the fragmentary, in the unbalance, so let’s see, and it’s almost finished. And the last part is about Reykjavic and Bobby Fischer, the chess champion. I know he ended his life very full of hatred. He was exiled here; he’s buried here, so I have been able to go to his grave. When I was five, six, maybe seven years old in Cuba, my father talked to me about Fischer, an American hero, who had been in Russia and here in Reykjavic, and the word “Reykjavic” meant something to me as a child. So there is also something karmic.

I didn’t apply for this city. I applied to ICORN, the NGO. You don’t know where you’re going. And they were like, “Well, there aren’t too many options. There are very many applications. We have something, but I promise you won’t like it. It’s at the end of the world.” “What is it? Tell me.” “Well, there is an opportunity now in Reykjavic.”

RA: And they didn’t know that you like cold weather. Why would a Cuban want to go to Iceland?

OLPL: When I arrived the first time from New York, at 6:00 a.m., I was in tears. Now I think I will be returning to this country. Not to a city, as I told you, but to a farm, to help an old family there. I will be happy. But to do that I will need some ground under my feet to be able to have money, to be able to have a profession, to be able to publish more. At least that’s what I think right now. It’s very beautiful, and the winter was very beautiful. Twenty hours at night. I love it. Everybody was warning me: depression.

RA: Well, you sounded depressed.

OLPL: I was posting about depression, but it’s not the same. I was sad for a time. It was the distance. I was channeling that. But not because the darkness was crushing me.

RA: I thought you were having seasonal affective disorder.

OLPL: It’s logical, yes. But I didn’t feel so much like that. I mean, you read my posts and they’re schizophrenic. It’s on purpose.

RA: I won’t take your posts that seriously any more.

OLPL: I spent three days without seeing the sun. I was sleeping during the day, and I would wake up at night, but after that I felt renewed, and I walked almost all day. I was happy, euphoric. Reykjavic is still very new to me. I don’t know the city at all. And I have been traveling a little in the country and saving a lot of Iceland for the future. And in America, too. It will be more repetitive in a way, but the challenge of reading, learning, and writing will be new for me. I don’t have a humanistic education; I was trained as a biochemist. And I’m happy.

Note from Translating Cuba: Regina Anavy has been supporting this project to translate Cubans writing from the island from its earliest days, in 2008. She has translated well over 300 posts (including many that appeared on earlier sites) and has supported and continues to support the project in other ways, not least of which is hosting us in her home.