Obispo Street, one of the oldest in Havana, begins in the sea and culminates in Monserrate. It is crossed by dozens of street ranging from the Avenida del Puerto and the neighborhoods adjacent to the Old Quarter, which increases its noisy and colorful vitality without diminishing the glamor lent it by its shopping centers, museums, libraries, hotels, banks, government agencies and other entities the Office of the City Historian is trying to restore.

Obispo Street, one of the oldest in Havana, begins in the sea and culminates in Monserrate. It is crossed by dozens of street ranging from the Avenida del Puerto and the neighborhoods adjacent to the Old Quarter, which increases its noisy and colorful vitality without diminishing the glamor lent it by its shopping centers, museums, libraries, hotels, banks, government agencies and other entities the Office of the City Historian is trying to restore.

Only the Municipal Acts, some newspapers and magazines and two or three history books about the Cuban capital relate the names and locations of the various centers that made Obispo into “the street of the streets,” followed later by Galiano, San Rafael and Prado; it is even compared for its elegance with Rue de Paix (Paris), San Fernando (Barcelona), La Sierpe (Sevilla), the Carrera de San Jeronimo (Madrid) as well as the aged streets of New York.

Almost no one remembers that until 1898 it was crossed each morning by a company of Spanish volunteers who marched under the strains of a band, from the Prado to the sea, where they were spread out to guard the Palacio de los Capitanes Generale, the Palacio del Segundo Cabo, the Castillo de la Fuerza, the Spanish Bank and other civilian and military defenses of the colonial period.

Despite the weather, the expropriations of the 1960s and the circumstances that marked the urban involution, Obispo retains its original layout of a noisy, narrow street with shops on both sides of the pedestrian sidewalk passersby who disappear into a corner, go to a boutique or head off to a scheduled meeting.

Centuries later, Obispo oscillates between a colonial provincial atmosphere and a sense of modernity brought by the merchants and public figures during the Republic. The paving stones were replaced by asphalt, reborn entities and stores in ruins, like the House of Happy Father Varela, recycled into a school library; the Hotel Florida, which had among its guests the Spanish philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal in 1937; the Almendrares optician and Café Europa, literary scene of the narratives of Carlos Loveira and Luís Bonafoux.

The University of Havana started on Obispo Street, where it was located between 1728 and 1902 in the Dominican Convent, also the venue of Secondary School of Havana, whose students snack in front, in the The Angel Bakery or in the French pastry shop, Brasy. On demolishing the convent, in the late 50’s, the building of the Ministry of Education was built, which shares space with real estate offices.

Where the current Ministry of Finances and Prices was once the Wilson House perfumery and National Bank built by the tycoon Pote; later it was occupied by the General Treasury of the Republic and the Ministry of Finance. Poe should also be credited with The Modern Poetry bookstore, built in 1900 at Obispo and Bernaza, opposite the Ricoy bookstore, now Cervantes, where eminent personalities from the country’s cultural and political spheres met.

These were followed by the Anselmo Lopez piano store, the ironmonger’s, and the Bosque de Boloña store, later relocated to the corner of Compostela. Almost at the beginning and near the Plazoleta de Albear were found the El Casino hat store, and the La Cebada cafe, very popular with the drivers until its sale and conversion to the Floridita Bar, home of writer Ernest Hemingway, who stayed at the hotel Ambos Mundos before acquiring the Vigia in San Francisco de Paula.

Historians and planners say Obispo Street, so hot in summer and cold in winter, owes its charm to its geographical position and the network of shops, banks and bureaucracies, refined by the latest offers of clothing and the cultural flow triggered by the installation of printers, newspapers, bookstores, publishing houses, law firms, pharmacies and other agencies the diverse social sectors attract, turning it into an urban paradigm.

Among financial centers We think of the Bances y Conde Bank, the Spanish Bank, which went bankrupt in 1921, the Trade Development Bank, the Trust Company of Cuba and the Núñez Bank, considered in 1957 to be among the world’s most important institutions.

Among financial centers We think of the Bances y Conde Bank, the Spanish Bank, which went bankrupt in 1921, the Trade Development Bank, the Trust Company of Cuba and the Núñez Bank, considered in 1957 to be among the world’s most important institutions.

Obispo integrates the tangible and spiritual heritage of Havana. Many establishments have disappeared, but are the Johnson and Taquechel drugstores are kept, the Anteojo Opticians, and the old houses are repaired for Museums (La Plata), libraries and offices (Department of Housing and Land Registry) and restaurants and cafes for tourists.

September 26, 2010

Yadima Évora Casales is a 25-year-old Cuban mother from Vista Hermosa in San Miguel del Padron, Havana. She believes she is a victim of deceit and manipulation at the hands of officials from the institutions that “respond” to the interest of the country’s citizens.

Yadima Évora Casales is a 25-year-old Cuban mother from Vista Hermosa in San Miguel del Padron, Havana. She believes she is a victim of deceit and manipulation at the hands of officials from the institutions that “respond” to the interest of the country’s citizens. She was told by Joel L. Carbonell that she must combine her plea with the demand, since article 26 of the Cuban Constitution allows for “reparation and compensation” for damages caused by State agents and officials. She also learned about the rules for the protection of children and youth and the obligations assumed by the island’s government when they agreed to the terms of the Instruments for Human Rights and the Conventions of Children’s’ rights.

She was told by Joel L. Carbonell that she must combine her plea with the demand, since article 26 of the Cuban Constitution allows for “reparation and compensation” for damages caused by State agents and officials. She also learned about the rules for the protection of children and youth and the obligations assumed by the island’s government when they agreed to the terms of the Instruments for Human Rights and the Conventions of Children’s’ rights. On Tuesday, June 15th, I ran into Juan Juan Almeida in the International Legal Office on 21 24, El Vedado. As we said goodbye, he told me he was starting a hunger strike on that day demanding the exit permit to continue his medical treatment outside Cuba. I visited him twice at his apartment on 41 and Conill before August 23rd, when he suspended his fast at the request of the Archbishop of Havana, who interceded on his behalf before General Castro’s government.

On Tuesday, June 15th, I ran into Juan Juan Almeida in the International Legal Office on 21 24, El Vedado. As we said goodbye, he told me he was starting a hunger strike on that day demanding the exit permit to continue his medical treatment outside Cuba. I visited him twice at his apartment on 41 and Conill before August 23rd, when he suspended his fast at the request of the Archbishop of Havana, who interceded on his behalf before General Castro’s government. I don´t think he worries much about the conflicting opinions of those who judge him through a political lens. Juan did not distance himself from the power circle in order to climb in the opposition. As I listened to him on Monday, August 23rd, I thought that this charismatic and cheerful down-to-earth Cuban believes more in the smile and the handshake of those who greet him than in all the slogans and hallelujahs he heard since he was born.

I don´t think he worries much about the conflicting opinions of those who judge him through a political lens. Juan did not distance himself from the power circle in order to climb in the opposition. As I listened to him on Monday, August 23rd, I thought that this charismatic and cheerful down-to-earth Cuban believes more in the smile and the handshake of those who greet him than in all the slogans and hallelujahs he heard since he was born. As in medieval times, when music, painting and other artistic expressions were under the wing of the Catholic church, in Cuba culture is sponsored by the State. But artists don’t knock on the doors of cathedrals nor present their projects to the despot, since there is a network of institutions that rule and control film, the performing arts, the plastic arts, books and literature, architecture and even the media.

As in medieval times, when music, painting and other artistic expressions were under the wing of the Catholic church, in Cuba culture is sponsored by the State. But artists don’t knock on the doors of cathedrals nor present their projects to the despot, since there is a network of institutions that rule and control film, the performing arts, the plastic arts, books and literature, architecture and even the media.

There’s an overflow of charm and splendid performances upon that altarpiece of scenic passions, where comedy wins the bout over tragedy and the masks reveal something of the mythic and the ordinary, without evading the problems of the present and future.

There’s an overflow of charm and splendid performances upon that altarpiece of scenic passions, where comedy wins the bout over tragedy and the masks reveal something of the mythic and the ordinary, without evading the problems of the present and future. On Saturday, August 7, Cuban television aired another chapter in the media tragicomedy of Fidel Castro Ruz, who chaired the special session of the so-called People’s Power National Assembly, to which he spoke about the disaster that will be triggered in the Persian Gulf if the U.S. government dares to underestimate the threats of Iran, whose government is developing a plan of nuclear weapons, destabilizing the region.

On Saturday, August 7, Cuban television aired another chapter in the media tragicomedy of Fidel Castro Ruz, who chaired the special session of the so-called People’s Power National Assembly, to which he spoke about the disaster that will be triggered in the Persian Gulf if the U.S. government dares to underestimate the threats of Iran, whose government is developing a plan of nuclear weapons, destabilizing the region. There’s a discrepancy between the sign board and program schedule at the Casa Gaia, located in Teniente Rey, between Águila and Cuba Streets in the historic quarter of Havana. That’s where art and thought now come together, but the sign board at the entrance announces the staging of Flechas del Ángel del Olvido (The Angel of Oblivion’s Arrows), scheduled to run Friday through Sunday until 29 November, under the direction of Esther Cardoso Villanueva, the director of the center.

There’s a discrepancy between the sign board and program schedule at the Casa Gaia, located in Teniente Rey, between Águila and Cuba Streets in the historic quarter of Havana. That’s where art and thought now come together, but the sign board at the entrance announces the staging of Flechas del Ángel del Olvido (The Angel of Oblivion’s Arrows), scheduled to run Friday through Sunday until 29 November, under the direction of Esther Cardoso Villanueva, the director of the center. As August progresses, as if the summer sun and rain weren’t enough, the official press is punishing us with news that tests the boundaries of even the complete joke represented by the newspaper Granma, the Communist Party organ, and Juventud Rebelde — Rebel Youth — the newspaper for the younger generation, two sides of the totalitarian coin, accustomed to embellishing statistics, interviewing “leaders” and courtesans, pointing their magnifying glass at events in the United States and giving a pat on the back to allies like Iran and North Korea.

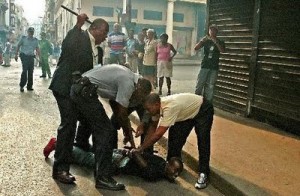

As August progresses, as if the summer sun and rain weren’t enough, the official press is punishing us with news that tests the boundaries of even the complete joke represented by the newspaper Granma, the Communist Party organ, and Juventud Rebelde — Rebel Youth — the newspaper for the younger generation, two sides of the totalitarian coin, accustomed to embellishing statistics, interviewing “leaders” and courtesans, pointing their magnifying glass at events in the United States and giving a pat on the back to allies like Iran and North Korea. From the silence, the impunity, and with the same contempt for the activists who promote human rights in Cuba, the political police triggered the arrests and threats in Havana and other cities in the country, between July 10 and August 12, which coincides with the resumption of activities by ex-president Fidel Castro and the official celebration of his birthday, on Thursday, August 13.

From the silence, the impunity, and with the same contempt for the activists who promote human rights in Cuba, the political police triggered the arrests and threats in Havana and other cities in the country, between July 10 and August 12, which coincides with the resumption of activities by ex-president Fidel Castro and the official celebration of his birthday, on Thursday, August 13. Ricardo Medina, a theologian and representative of the Liberal Catholic Church was arrested on August 4 together with the activist Hugo Damián at the Pinar del Rio bus station, where he was to greet the layman Dagoberto Valdés. He was taken by an official from State Security with Ricardo’s dossier, and freed two days later.

Ricardo Medina, a theologian and representative of the Liberal Catholic Church was arrested on August 4 together with the activist Hugo Damián at the Pinar del Rio bus station, where he was to greet the layman Dagoberto Valdés. He was taken by an official from State Security with Ricardo’s dossier, and freed two days later. As a teenager I imagined that writers were wise, sensible, creative, focused and responsible people. For me, a poet was a chosen of God in communion with men, capable to singing to the moon, describing encounters with the stars, and shouting the word freedom before the rifles of the tyrant. With the passage of time I met several literary types and discovered the human profile of some poets and writers.

As a teenager I imagined that writers were wise, sensible, creative, focused and responsible people. For me, a poet was a chosen of God in communion with men, capable to singing to the moon, describing encounters with the stars, and shouting the word freedom before the rifles of the tyrant. With the passage of time I met several literary types and discovered the human profile of some poets and writers. In closing, we must point out that: “One of the most harmful forms of fear is the one that masquerades as common sense or prudence, and rejects as thoughtless or frivolous small acts of courage that maintain the sense of dignity and respect for oneself. ”

In closing, we must point out that: “One of the most harmful forms of fear is the one that masquerades as common sense or prudence, and rejects as thoughtless or frivolous small acts of courage that maintain the sense of dignity and respect for oneself. ”