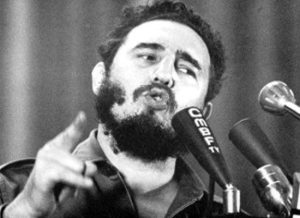

Cubanet, Tania Diaz Castro, 13 March 2017 – This 13 March is the 49th anniversary of the Great Revolutionary Offensive, that economic project that emerged from the little brain of the “Enlightened Undefeated One,” to ruin the Cuban economy even further.

Although each year the so-called Castro Revolution was a real disgrace for all Cubans, the worst of all was the day that Fidel Castro did away with more than 50,000 small private businesses: establishment where coffee with milk and bread with butter was served, high quality restaurants mostly for ordinary Cubans; expert carpentry workshops; the little Chinese-run fritter stands; fried food stalls which, for those who don’t remember, used prime beef; shoe shiners who plied their trade along the streets; people who sold fruit from little carts; milkmen who delivered to homes, etc. A project that caused unemployment among workers with long experience and that upset people. continue reading

Under the slogan of creating “a New Man,” something that today inspires laughter, the Great Revolutionary Offensive is no longer mentioned. Not even one more anniversary of that nonsense is mentioned in the media, as if nobody remembers the great mistake of the Commander in Chief.

The “New Man,” proposed as a part of this, ended up losing his skills and trades forever: cabinetmakers, turners, gypsum and putty specialists, blacksmiths, longtime carpenters, tailors, seamstresses, book restorers and many others, were forced to give up their work and take up screaming “Homeland or death, we will win!” Over the years, between the invasive marabou weed and the “magic” moringa tree, they were converted into the now well-known undisciplined, lazy, lethargic, absent, stealing in their workplaces and dreaming of working outside their country. A kind of worker who, it is true, thanks to the crazy economic juggling of Fidel Castro, is inefficient even faced with cutting-edge technology.

A recent example has been widely commented upon by Havanans: two hundred Indian workers have been hired for the construction of the Gran Manzana Kempinski Hotel, under the argument that Cuban workers cannot deliver the same performance.

Those who ask whether this is appropriate, seem to have forgotten that Cuba still suffers the great drama of lost trades.

The elders of today, who analyze everything through the great magnifying glass of time, come to the correct conclusion that these workers have been not only victims of the economic disaster that the country suffers, and then converted by force into members of a first opposition against the regime, an opposition that has done a lot of damage and the result of which has been to live in a country lacking development and technology for decades and, therefore, instead of good pay they receive alms, as a punishment to shame them.

Raúl Castro said it recently: “We have to erase forever the idea that Cuba is the only country in the world where it is not necessary to work.” Would it not have been more accurate to say: “the only country where people do not want to work, so that the socialist dictatorship will end?”

That would be the real solution.

If Raul does not say it, it is because he is afraid to be sincere. Miguel Díaz Canel, his first Vice-President, may say it through his always lost looks, as lost as those trade that reigned in a Cuba that was not Fidel’s.