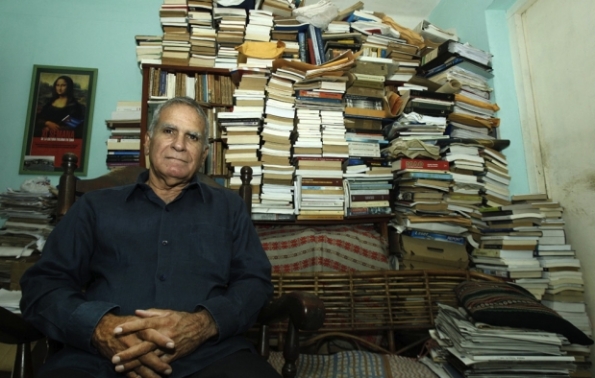

One of the central figures of the Cuban opposition, who participated in the revolution before its ultimate victory but ended up being sentenced to 20 years in Castro’s prisons, was the independent economist Oscar Espinosa Chepe, who died in Madrid. He recounts his life and ideas in this interview.

Born in Cienfuegos on November 29, 1940, Chepe joined the revolutionary movement while studying at the Instituto de Segunda Enseñanza in that city. After 1959 he held various positions in the Socialist Youth (JS) and in the Association of Young Rebels (AJR), in the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), in the Central Planning Group (JUCEPLAN) and in the office of Prime Minister Fidel Castro.

He was punished for his opinions by being made to collect bat guano from caves and to work in agriculture. While on the State Committee for Economic Collaboration he was in charge of economic and technical and scientific relations with Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. He served as economic adviser at the Cuban Embassy in Belgrade and as a specialist at the National Bank of Cuba, from which he was fired for his beliefs in 1992.

Thereafter, Chepe worked as an economist and independent journalist, for which he was sentenced to 20 years in prison in March 2003. He was released on parole in November 2004 due to ill health.

The following interview of Chepe was conducted by Dimas Castellanos in Havana in 2009.

DC: You are described as an economist or an independent journalist, but we know little about the other aspects of your life. What were your early years like, your family environment?

OEC: I was born in Cienfuegos. My parents were from humble origins. They had business dealings with a string of pharmacies. My mother was also involved in the real estate business and together with my father came to own a drugstore in partnership with other people. I had a happy childhood but I was always interested in history, politics and social justice. My father encouraged these interests. He was a member of the old Communist Party and participated in the struggle against the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, a cause for which he spent time in prison. During my undergraduate studies, I established contacts with members of the Socialist Youth (Juventud Socialista, or JS). continue reading

I participated with the JS and other students in demonstrations against the Batista dictatorship. During the sugar strike of 1955 students were going to workers’ assemblies to encourage them to join the strike. At these activities I met union leaders who would later belong to the People’s Socialist Party (PSP).

Did you suffer any consequences as a result of your activities?

In 1957 I was accused of a sabotage attack in Cienfuegos. I had no involvement but I was imprisoned and tried by the Emergency Court of Santa Clara. At the trial I was defended by the man who would later become President-of-the-Republic, Dr. Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado. I was acquitted but the threat from the chief-of-police of Cienfuegos forced me to leave town. For that reason I came to Havana and began my studies at a school called Candler Methodist College, where I continued my political activity. That’s why I was expelled from the school in early 1958.

In what political organization were you active at the time?

I was a member of a student movement called the March 13th Revolutionary Directorate until the triumph of the Revolution. Then, after the JS was reorganized and it became the youth organization of the People’s Socialist Party, I re-established ties with the organization. I was its president in Cienfuegos and a member of the provincial committee in the former province of Las Villas until youth organizations were folded into the AJR. I was then in charge of propaganda for the provincial committee in Las Villas and served on the national committee. While in this organization, I helped set up committees in Cienfuegos as well as those in rural areas that had opposed the government.

I remember a peasant leader who was working with us, Juan Gonzalez, who was later killed in an ambush. Much later, when I was on the Provincial Committee, one of our drivers was killed in another ambush. His name was Hector Martinez. He was a humble young peasant and, like all of us, very eager.

It was a very sad period, a time when Cubans were caught up in a war that made no sense because it was a war between brothers. The government cruelly evicted many families from the mountains. They lost their land and their belongings because it was thought they were cooperating with the rebels. The departure of these families created ghost towns in Pinar del Rio and other provinces.

It was a bloody period, one when hatred prevailed. It lasted several years and in the end totalitarianism won by instilling fear in society. Cubans as a whole, including those who risked their lives for an ideal, were shattered.

Was there anything from that period that had an impact on you?

There were many things. While I was in Cienfuegos, I remember the first militias that went to fight in Escambray. I was part of a battalion that was took over Cayo Loco, where we found remnants of Batista’s navy, which were under suspicion. I also remember the enthusiasm of that era, when the revolution had overwhelming support.

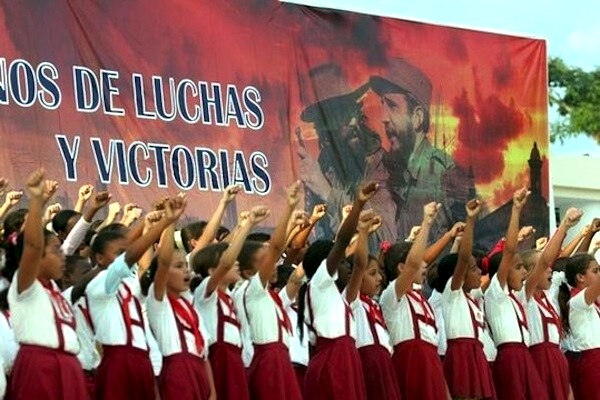

Another emotional moment was when the revolution was declared to be socialist. I was speaking at an AJR assembly in Sanctus Spiritus and suddenly there was a huge crowd in the street waving red flags and shouting, “Long live the socialist revolution!” And Fidel Castro made the proclamation in Havana on the eve of the Bay of Pigs.

The next day, after we found out about the landing on the beach, I boarded a jeep with 30-caliber machine guns — not knowing where we were going — to protect the airport at Santa Clara. I was somewhat like a commissar, with militiamen who did not have much experience but had a total willingness to sacrifice. Our mission was to protect this strategic location, which was not far from the Ciénaga de Zapata, from aerial attack. Fortunately, nothing happened.

Those experiences had a big impact on us. We thought we were going to turn Cuba into a paradise and people were full of hope. We had total confidence in the future, in our leaders, especially in Fidel, in Che, in Raul. To many of us from the JS our greatest inspiration was Raul Castro. We knew he had been in the JS. It was a time of tremendous enthusiasm and naivete, feelings that subsequently gave way to colossal frustration.

After that first experience in the youth movement, did you join any other political organization?

I joined the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI). I became core secretary at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), where I was departmental head when the party was forming within the ORI. There was Antero Regalado, an old peasant leader, and other directors who held high-level positions in INRA.

At that time was the INRA something of a parallel government?

Yes, yes, it was a government. Even the agrarian development zones were almost republics. The heads of those zones confiscated land and had tremendous power. In supply planning, where I worked, they first put a Latin American in charge, but the man turned out to be a disaster. There was no one else to take his place, so they put me in charge. I was about 21 or 22-years-old and my only qualification was a high school diploma.

I remember at the time they fired an engineer, Santos Ríos, from INRA. Fidel Castro was President but in effect he was running the agency. After they removed Santo Ríos, they appointed Carlos Rafael Rodriguez president of INRA. I was given a position I didn’t want because he knew I had no experience. My goal at the time was to study economics at the University of Havana. There were also some special plans over which only Fidel Castro had control. Three weeks after completion of the one-year plan, Fidel’s envoys appeared with different plans, so all our work had to be thrown out and resources had to be reallocated to other planning projects. It was crazy.

After that did you hold some other position within the government?

Later I transferred to JUCEPLAN. There were big turnovers there and they asked Carlos Rafael for additional personnel. I was one of those selected. I went to work in the agricultural sector as department chief in the Supply Plan for Agriculture and Fisheries. I worked by day and studied economics by night at the University of Havana until the economic research teams were created. Then I was chosen to work on the livestock team.

A few months after these teams were formed, it seems that Fidel Castro decided he wanted some of them to work directly with him. We were relocated to 11th Street, near the home of Celia Sanchez. I did as I was told. I was assigned to a group specializing in artificial insemination. It was crazy because insemination is supposed to be done with animals specially selected for certain traits. Instead, they were inseminating any cow who happened to come along.

At the time I went to the countryside and realized what a mess it was. It was the peasants themselves and the INRA directors who showed me how bad things were. Around this time I began reading the works of some socialist economists. Among the Soviets I remember Liberman. Among the Poles there was Oskar Lange, W. Brus and M. Kalecki, who provided critiques within a socialist framework.

I began to realize a lot of things. Working with Fidel I understood that some things were irrational, such as the abolition of material incentives, which Che had championed, the systematic gutting of accounting systems and economic controls, and especially the mass confiscation of private property.

I was a spectator to the conflict between Che Guevara on the one hand and his defense of the budgetary finance system, which proposed to monopolize the entire economy, and Carlos Rafael Rodriguez on the other and his support for a more rational and flexible style of self-management.

I later discovered, however, that in such a dysfunctional system this too was impractical. When it came to theory, Carlos was brilliant but, though he was astute, he did not engage with Che directly but rather through third parties. Che was a man who was completely wrong when it came to economic theory. History has amply demonstrated this and the budgetary finance system is not even mentioned in Cuba today.

In light of the situation, I shared my views with my team. After I defended them, they took me to a meeting to try to dissuade me from my “misconceptions.” I remained unconvinced so they then took me to have a discussion with José Llanusa Gobel, who at the time was Minister of Education and someone very close to Fidel Castro.

What happened at this meeting?

We had a heated discussion. He tried to convince me, which made me increasingly more steadfast in my beliefs about the very things he was talking about, such as building communism and abolishing money. I asked him what the economic and rational basis for this was. I acknowledged that there had to be moral incentives, but at the same time you had to pay people more, in accordance with the quantity and quality of the work they performed. This is the position Raúl Castro himself ultimately adopted. Llanusa told me I was evil.

A short time later they bought a bull in Canada that looked like an elephant. We got word that we should go see it. Fidel was there. He was very impressesd, walking all around it. Later, the bull was discovered to have been injured. It seems they took too much semen from him before he was sold, which made him damaged goods. Llanusa arrived while I was there and went off to talk with Fidel, so we left. The next afternoon Fidel arrived at our office with his bodyguards and began saying offensive things to me.

“We know who you are hanging out with and who you are meeting.”

I said, “Look, Comandante, you have been misinformed. I am not meeting with anyone nor hanging out with anyone. I am just telling you what I have been taught at the University of Havana.”

He took that as a sign of disrespect and became enraged. I only told him the truth. My point of view was based on what I had studied at the university. Many of our classes were taught by Soviet or Hispano-Soviet professors and our basic textbook was Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. From that moment I wanted in some way to oppose his program. I could not remain silent in the face of so many blunders and nonsensical policies which, among other things, were direct contradictions of basic Marxist principles.

Did this lead to any repercussions?

Two or three days later the head of the team called me in and told me I had to leave. That was in June 1967. They sacked me but kept sending a paycheck to my house until January 1968. At that time the “micro-faction” trial was taking place. Then the party secretary in Havana, a man named Betancourt, called to ask me what I thought of the trial since the statements of the accused happened to coincide with some of things I had done. Then he asked if I still felt the same way.

I said, “Yes. If I told you that I had changed, I’d be lying. Do you want me to lie?”

He said, “Then we’re going to send you on a heroic mission in order to reform you. And what you’ll find is that you have never worked so hard in your life.”

They sent me to clean bat guano out of caves such as La Jaula, which is on the road towards Escalera de Jaruco in Quivicán, and in Pinar del Río, where I got sick. As a result they transferred me from there to the Havana Green Belt to work in brigades of people convicted of petty crimes. It was very humiliating for me because I considered myself a revolutionary. It was a hard time but I still believed in the revolution, still thought mistakes were being made and had to put up with it until they were corrected, but time passed and nothing was resolved.

After all that how was it possible you went to work in the foreign service?

After almost two years of punishment I wrote to Carlos Rafael Rodríguez and also to Osvaldo Dorticós, who had known me in Cienfuegos. Then one fine day Llanusa called me and apologized. He told me he had made a huge mistake, that he had never ordered them to do this to me and asked if I would go work for him. I told him no, that I would not work with him. He asked me where I wanted to work. I said in the Ministry of Sugar with Miguel Ángel Figueras, an economist who had been my professor and who was vice-minister there. He picked up the phone, called him and immediately I began work at the ministry, though I was really very disillusioned.

One day I went to the Technical Assistance Center (CAT), where Humberto Knight was the coordinator. He was a little leery and asked if I really wanted to work there. I said yes because I had always admired Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, who headed that office. Carlos Rafael was a very intelligent and educated man. He had been a member of the old Communist Party. I started working there in an auxiliary capacity but I devised a comprehensive methodology for evaluating the work of foreign specialists and was congratulated by high-level officials from other organizations. Then Carlos Rafael called me in to explain it to him. When we started talking, I told him, “Doctor, you were commissioner in Cienfuegos at the end of the revolution of ’33.”

He asked me, “How do you know that?” He then looked at me and blurted out, “Oh, aren’t you the son of Oscar Espinosa?”

It so happened that my father once told me that he had participated in the creation of a soviet, was taken prisoner and was sent to Havana. Then Carlos Rafael, who held a position in the Hundred Days’ government, looked at him and said, “Come along. You’re going to be a prisoner of the revolution.”

Then my father responded, “This isn’t a revolution; it’s a piece of shit.”

This offended him. At times my father could be somewhat aggressive and the Communist Party of that era was extremely arrogant and sectarian. Carlos Rafael told me the same story during our conversation and said to me, “Your father was a shithead. Are you going to be like him?”

In short I worked with him, a few yards from his office in the Palace of the Revolution, dealing with relations with Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Then I also began dealing with the economic and scientific-technical ties with Yugoslavia. I must admit that, in terms of opportunity, I enjoyed working alongside Dr. Rodriguez, as he was respectfully referred to overseas. I learned a lot, especially in regard to his penchant for anti-dogmatic opinions and open dialogue. Given the position he held, he reserved his personal opinions for a narrow circle of people, though there was never any doubt he was a committed Marxist.

What did you do there?

I sat on intergovernmental commissions and served as secretary on those commissions. I also held discussions with our foreign partners on setting up accords, general conditions of co-operation and state credit agreements, some with special governmental powers. This was quite unusual considering I was never a member of the Cuban Communist Party, which was a basic prerequisite for participating in these types of negotiations.

Later we moved to First and B streets in Vedado. It was then that I began to travel. My first trip was to Hungary in 1973, which I made with Carlos Rafael. It was awful. There was an enormous number of documents to be signed and when I looked over them, I realized half of them had not been signed. Carlos Rafael and Miklos Ajtai, the Hungarian vice-president, were supposed to have signed them. I thought this was going to be a disaster. I spoke openly with Carlos Rafael and explained to him what had happened. He said, “No problem. Bring them over,” and the two of them set about signing them, even though the signing ceremony had already been televised.

I also spent many years as secretary for Czechoslovakia and participated in many conferences with vice-presidents of the Cuban government. With José Ramón Fernández, Ricardo Cabrisas and other senior leaders for example. My department also oversaw the commercial interests of the State Committee for Economic Cooperation. We had a good working relationship, but I think he appointed me departmental head because of the problems he had with Fidel Castro.

What was not approved?

I was never formally appointed. It was a position with the Central Committee but I was not appointed. I was there for ten years, negotiating millions of rubles worth of business. We later went to the ministries, and ministers the vice-presidents provided signatures. It was for different types of business, such as sending young people to work in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. I am talking about volunteers. I worked out the language in all those documents. In the case of Czechoslovakia I held discussions with the Czech vice-minister.

But things did not go well. What happened was that they told the kids they could not bring this thing or that thing, that they could keep only a portion of the money they were paid and the rest they had to turn over to the government. Nevertheless, the kids were dying to go. The Czechs and Hungarians also complained that our young people were all in love and always screwing around but, when it came time to work, they were better than those from other countries.

How long did you do this type of work?

I dealt with Hungary and Czechoslovakia until 1984, when I was made economic advisor in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. I had an office and a lot of autonomy. This situation created a lot of tension with the ambassador but in terms of the work itself I had no problems. It was the beginning of perestroika and I had said that I was in agreement with Gorbachev.

When a Yugoslav man approached me, I immediately informed the security office of what had happened but I waited a few hours before informing the ambassador. They took advantage of the situation and used it as a pretext to get rid of me. Fidel had been there during a visit to Belgrade and had seen me. From the look on his face it was obvious he was not happy I was there. Then, when I went back to Cuba in April of 1987 for vacation, they told me I could not go back. They told me they were trying to protect me, that the enemy was trying to do me harm. They didn’t even let me go back to collect my things. My wife Miriam was also a diplomat in charge of cultural affairs, press releases and sports. They let her go back to collect our belongings and she kept working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but I was prevented from working in the diplomatic field and was sent to work at the National Bank.

I was a specialist dealing with businesses affiliated with the National Assembly of People’s Power and the Ministry of Domestic Commerce. I started making statements about the need for reform. In March 1992 I was summoned to a meeting where they even brought up my problems with Fidel. They told me that I was raising issues that had already been discussed at the last party congress. I stated that I did not have to accept what the congress had agreed upon because I was not a party member. I began arguing with them, citing the congress’ own statistics. I was then removed from my post at the bank and sent me to work at a tiny bank near my house, which you and I both know, dealing with paperwork of no importance.

Anyway, little by little I began typing articles and sending them around, sharing them with friends. That’s how you and I became acquainted. Colleagues of Oswaldo Payá also began having contact with me. You later helped me transcribe the articles I typed onto a computer. Then my circle of acquaintances significantly widened. I had a program on Radio Martí called “Talking to Chepe” until I was arrested in 2003 and was was given a 20-year prison sentence.

What effect does a prison sentence have on a person like yourself who has dedicated his entire life to the revolution and to socialism?

It was very difficult, including what was a very delicate moment for me when I was being transported to Guantanamo to serve my sentence. Even the Batista government would have been more forthright in the way I was tried. The charges they brought against me were so crude. They accused me of being an American agent when everyone knew that I had never agreed with American policy. They accused me of meeting with certain American congressmen when they knew that I had told those congressmen they should lift the embargo. It was really awful.

I came to the conclusion that I had followed the revolutionary line but that it was the government itself that gone against that line, that it had become stagnant, conservative and counter-revolutionary. It wasn’t even nationalistic because through its actions it had distorted the national identity. It had forced millions of Cubans to leave the country while making a significant portion of the remaining population want to leave the island as well.

Do you feel hatred to some of the people who caused you harm?

No, I try to avoid hate because it stifles your intellect. You have to look for a point of reflection in order to try to understand because some things are not easy to understand. I have come to the conclusion that in Cuba there can be no end to the crisis without reconciliation. Cubans have only one possible path, like in Spain, like in Chile. Of course, there can be justice — justice for everyone — but Cuba has no way of solving its problems unless it is based on national compromise and reconciliation. We have to look for compromise.

I envision initiating a dialogue that might end — as happened in the 1930s — with a new constitution that resembles as much as possible the constitution of 1940. The situation now is so serious that we have to take a series of measures such as granting peasants access to the land, increasing the range of self-employment options, legalizing small and medium-sized private businesses and later establishing a truly representative constituent assembly like the one in 1940 that included conservatives, Christians, communists, liberals, everyone. That’s my proposal.

Before, however, you felt hatred. Does this mean you have evolved?

Yes, that was a phase. I have to acknowledge that I came from the communist ranks, where they used to talk about class struggle and where in a certain way they preached hate, but I have overcome all that. I have realized that it doesn’t get you anywhere, that it doesn’t allow you to be analytical, because you start off with a series of prejudices which leads to a biased analysis.

Of course, I am human and I have feelings. They have haunted me at times and at any given moment this type of sentiment can disrupt any analysis I might be doing, but I try to avoid it. I don’t get upset about it. I look at Cuban leaders in a positive light when they say things I believe to be correct.

For example, Raúl Castro gave a speech on July 26, 2007 that I believe to be that of a realist and I have said so. Many people have attacked me for that and for many other things that I said about people who are not exactly friends of mine. I think I must stick with this approach so that hatred and prejudice do not blind me and prevent me from looking at things analytically. There is a rule I try to follow, though I don’t know if I always succeed, which is to have a warm heart and a cool head.

After revolutions succeed and their leaders come to power — becoming the law unto themselves — do other revolutionaries end up being the victims?

I am aware of that but that’s not revolution. What has happened here has been an attack on power by people who crave power above all else. That does not qualify as revolution. The fact that a revolution may have been violent does not mean that all revolutions have to resort to violence. There are many revolutions in different spheres of human life that have led to advancement, to development, to progress. I don’t necessarily associate revolution with violence.

Given all that has happened to you, have some of your ideas changed?

I have come to the conclusion that no one doctrine has a monopoly on truth. I believe, for example, that those promoting private property and those promoting public property are not mutually exclusive. They can co-exist. There are countries in the world where there is real public property — not like in Cuba, where it’s an illusion — and private property as well. There are markets; there is competition. In other words, the two things are compatible. The most successful societies in the world are those that have adopted this model in one way or another.

For example, in terms of living standards, wealth per capita, transparency and low levels of corruption as measured by the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Index, nations like Holland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Canada and Denmark rank high. Each has its own peculiarities, so they cannot be copied. But that is the way.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the recent world economic crisis have demonstrated that neither extreme individualism nor total state control offers solutions. We must go in search of a society where private property exists because the desire for social status and material success — within certain regulatory boundaries and controls — can be extremely beneficial.

But at the same time public ownership is also useful because in many sectors the potential profits are not large enough to spur private initiative and therefore the state must play an important role. Although they do not produce high returns, certain activities such as education, public health and other areas require the state to be involved for the reasons discussed or for strategic considerations. I am referring, of course, to a democratic state.

Do you consider yourself to be a Marxist?

No, frankly I would say no. When asked if he was a Marxist, even Marx himself said no. Marx is a man who must be looked at in the context of his time. The problems of the 19th century are not those of today. To look to Marx for solutions to our current problems is a mistake. Even some of his basic proposals did not come to pass.

His follower Rosa Luxemburg recognized through her own analysis that his theory of the impoverishment of the working class did not hold up. The prediction that socialism would first triumph in Western Europe, where there was a larger and more developed working class, also did not come true. I don’t think Marx had aspirations to be a soothsayer. There is only one passage in the Critique of the Ghota Program which speaks about the future. For that reason I am not a Marxist; I find that absurd.

I believe the world needs a series of solutions that can be found in neither the 19th nor the 20th century. They have to be devised now. Even institutions that were valuable in the 20th century, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, will have to adapt to new circumstances. Some concepts which were valid in the past are obsolete today given the unstoppable advance of globalization, science and technology. By necessity new ways of thinking and interacting in the world will have to be implemented.

I believe that international cooperation will play a much more important role than it has so far. In turn there will be a better chance of fighting ignorance, hunger and poverty on a global scale, as well as the challenges to human life brought on by environmental impacts. I’m sure this process will lead to the strengthening of the United Nations, giving this institution a much wider mandate.

Were you released “on parole?” What is that?

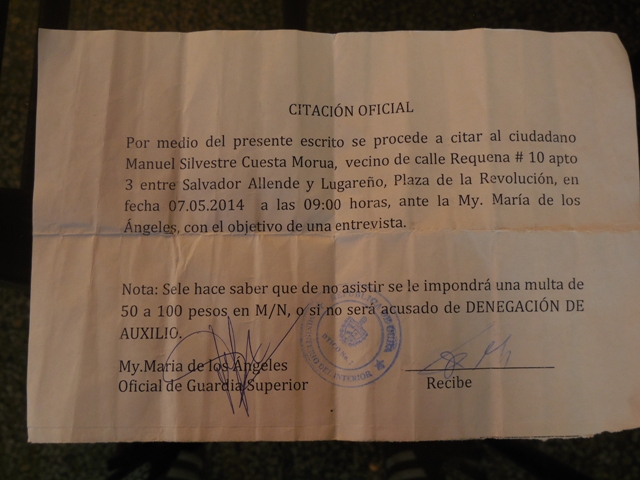

“Parole” for medical reasons means that I can go back to prison whenever I am considered cured, which is ridiculous since my illnesses are chronic. They summoned me to the Playa Municipal Provincial Court two years after my release to remind me of this, to tell me that I could not leave Havana without permission, that there was a commission in the neighborhood supervising me and, depending on what I say, I could go back to jail.

Above my apartment here, in #8, there is a State Security office that I think is monitoring me. They don’t even let me go outside. They apply different policies to different people. They allow some of those freed to leave. I have asked to go to the United States but they turned me down. I have even been invited to events in Poland, Puerto Rico and other places and, even though I have filed all the necessary paperwork, I have never received the authorization to leave: the famous White Card.

How did you see the relationship of economics to politics?

They are inseparable. In this regard Marx might have had some valid arguments. He used to say that society is based on production relationships and I still believe that, though I don’t deny that there is a relationship between the foundation and the framework above it. I believe that if there is more economic freedom, there will be more political freedom. Fidel Castro is very clear about this. He denies that there is economic reform because he knows that one thing leads to another and the consequences are inevitable.

The United States has imposed enormous restrictions on economic trade with Cuba: they don’t offer credit, you have to pay in advance, they don’t buy anything, you have to use foreign vessels. Nevertheless, with all these obstacles, the United States is now at least Cuba’s fourth largest trading partner. That is bound to have an impact. If there were more freedom, we would feel more in control of our own future. That would give us the motivation to fight for our political freedom, for the creation of a favorable economic environment.

The new law allowing individuals to lease agricultural land is full of snags and that is not by accident. It was carefully designed to make sure that people do not feel like owners. That is why I believe there is a very big correlation between economics and politics. Cuba is a country that has a geographical position and socio-political traditions are better than China’s. But even in China, with all its economic changes, people are beginning to push back. The protests there over the economic crisis and the closing of factories are huge, to say nothing of Russia.

Freedom is also an aspect of production. I defend this thesis because I believe competition plays a more important role than freedom of movement or freedom of thought. It allows you to choose the best option in a world with ever more choices, where dialogue and responsible, civilized debate are essential for sound and sustainable development.

From your standpoint what might be the main obstacles to change in Cuba?

The first is having the political will to move forward in a gradual way. I would begin with agriculture, giving land to people, giving them the means to pay for it, a way for people to come together on a voluntary basis. The state can retain a role in certain areas. There’s no contradiction there.

What the private sector will be and what the public sector will be will depend on results and concrete conditions. I think public involvement can be very efficient when it comes to education, public health and other sectors. Before the revolution students in Cienfuegos went from private primary schools to public secondary schools. It wasn’t because the public schools were free; it was because the quality was better. Private-sector education can be allowed to operate within certain guidelines, as was the case before 1959.

I came to Havana to go to a private school. You still had to pass the state exams. You have to avoid extremes. State extremism fell with the Berlin Wall and extreme capitalism fell the current economic crisis. Now Obama wants to guarantee health insurance for more than 40 million Americans and to improve public education, so he is being called a socialist. That’s nonsense. We must promote private initiatives as a key aspect of social progress and economic development but subject to regulation to curb excessive ambition and unjust enrichment.

Do you believe American policy is partly to blame for Cuba’s problems?

I do believe American policy has a degree of responsibility for this, a big one. I have always said that the Cuban government had two great allies. The Soviet Union gave a huge amount of economic support to the regime. But on the political side there has been the United States, with its unwavering stance, that has fostered totalitarianism. American policy and the embargo was like oxygen to the most conservative factions within the party.

Your book Chronicles of a Disaster? was published in 2003 and in 2007 Revolution or Devolution was published. Is there a direct relationship between them?

There is a direct relationship. They are collections of articles that express my viewpoints about the genesis of the Cuban drama, theories on how to overcome the crisis and proposals for national reconstruction in a framework of reconciliation that sets aside the hatreds that for so long have poisoned Cuban society. They cover different eras. Chronicles of a Disaster is about one era and Revolution or Devolution? is about another. I would say they represent a maturation in thinking, one achieved through reflection, dialog with others — including some with whom I disagree on several issues — and many years spent in opposition to totalitarianism.

For example, in the last book there is a series of articles I wrote about the Millennium Development Goals adopted by the UN. This led me to collect a significant amount of data and to study the history of Cuban economic theory, all of which showed that Cuba before the revolution was not the disaster that government propaganda would have us believe. This research has led me to the conclusion that, although there were serious problems hampering national development, from 1902 to 1958 Cuban had progressed in spite of its various governments and not because of the desires of those governments.

Cuban civil society had made advances in education and public health. In some significant ways such as the number of doctors per capita, life expectancy and infant mortality, the public health situation was better than that of European countries. Advances in education as well as in public health were comparable to those of Europe, not to Latin America, where the only countries comparable to Cuba were Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and perhaps Costa Rica.

Cuba did not begin in 1959, regardless of the fact that great strides were made in medicine and that educational efforts became focused on areas that had previously been marginalized, especially in rural areas. Unfortunately, even these accomplishments, which were achieved through the efforts of the people, are currently being undone due to the lack of necessary financial support.

In the introduction to Revolution or Devolution? Carmelo Mesa Lago writes, “The writings of Oscar Espinosa have inspired and influenced the work of many Cuban economists living overseas.” What does that statement mean to you and how did your training allow you to reach that level of professionalism?

Well, I am very flattered that a person whom I greatly admire and whom I consider to be the greatest living Cuban economist, someone who works for the International Labor Organization, has made this assessment of my work. For me that’s very heartening.

What I have done is to examine data and information, summarize and research official statistics, and look for misrepresentations. I rely on data from CEPAL, the UN, foreign publications and the Cuban press. If you were to go to my house, you would find thousands of clippings from periodicals and journals such as El País, ABC, El Mundo, El Nuevo Herald, The Economist and even official domestic publications such and Granma and Juventud Rebelde. I use them to analyze the economy as well and social and historical events. I really like history. It’s what I like most. I am a history nut. I always have a history book in my hand.

Often I see parallels in Cuban history. Many things seem to repeat themselves. For example there was Spain’s obstinate refusal to for carry out reforms and its rigidly conservative stance. Its insistence on not taking any action at that time became one of the root causes of the Cuban wars of independence. And now there’s something similar going on: the obstinance of the Cuban government means all doorways are closed off. So far there has been no danger of things blowing up, but no one knows if that will continue to be the case.

You have made important recommendations but the government, which would have to implement them, is not considering them. What is the significance of your work?

It is gratifying to know that my articles are read and heard on foreign radio stations. It is gratifying to know that some people access them through the internet or read them in newspapers published overseas. That some television interviews I give to foreign broadcasters make their way back here. That people tell me, “I saw you on television!” It is gratifying that friends are generous enough to make copies of them.

This is just the beginning; I am sure things will change for the better. Not too long ago we didn’t have the internet. Though there are a lot of hassles, we now have it. Who knows if one day soon I might also have it in my home.

Do you believe this tiny seed might germinate at some point?

That’s the idea, to sow the seeds of the future. I might live to see it or I might not, but I am modestly trying to independently collaborate on that because, as you know, I don’t belong to any organization. Sometimes I am asked to join a collaborative effort and I agree to do it. And if I don’t want to, I don’t agree to do it. And that’s how I participate, by offering my ideas. I do what I can. I even think that my work might, as you put it, be useful to the government itself. I hope it might help lead Cuba towards democracy. I would have no objection to that but I do not have any personal ambitions.

What do you feel would be the optimal outcome and what might be the possible outcome for Cuba?

To me the optimal outcome for Cuba would be something along the lines of the 1940 constitution. It seems to me that such a Cuba would be an expression of José Martí’s desire for a “republic with everyone and for the good of everyone.” It would be one in which individual aspirations are supported, one with private ownership where market forces are an important tool for the distribution of resources, where there is competition and the opportunity for improvement. There would be significant public participation that complements private initiative, but always within a democratic framework. There would be debates and political parties but we would not have to wait until an election is held to make decisions.

I think these things are possible; I don’t think it is a dream. It is something that other countries have achieved and I ask myself why we cannot also achieve the same thing through tenacity and through major investments in education and culture, which would lay the groundwork for fulfilling our destiny. I believe that throughout our history the Cuban people have demonstrated such motivation and aspiration, and can do so again.

What events have had a big impact on you personally?

Some things have had a big impact on me both positively and negatively. After the victory on January 1, 1959 I had a lot of dreams, though it all ended in enormous national frustration. It was a day I will never forget.

I was active in the youth movement and later I served as a diplomat, working to obtain advantages for my country. I have always fulfilled my duty and followed my conscience. Perhaps mistakes were made but they were always made with the best of intentions, trying to do something useful for Cuba.

As far as negative aspects go, there are also events that have had an impact on me. In 1967 I was expelled from economic research teams and was sent to clean dung out of caves and to work alongside criminals. In 1987 I was forced to leave the foreign service. In 1992 I was fired from the National Bank. They sacked my wife Marian from her job at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs just because she decided to stay with me. Another terrible blow came when I was arrested in 2003 and sentenced to twenty years in prison under inhuman conditions. All this was very hard but, you know, life goes on, thank God. I don’t know why. I’ve always pulled myself back up, though it wasn’t easy.

When your mother died, you were in jail…

My mother died a few weeks after I was released from prison, so I was able to be with her. By then she was very badly off. Much of the time she was unconscious and was suffering a lot. She was an example of hard work, of tenacity, of struggle and at the same time she was very tolerant. She never was a communist. She always rejected those theories. She was very devout but very tolerant. Even when I was involved in Marxist activities, she never objected. She respected my decision just as she respected it when I decided to oppose totalitarianism.

Do you feel fulfilled?

I feel fulfilled. I feel that I did something for my country. At certain times it was difficult because I was misunderstood by many countrymen, but I can also see the fruits of my labor. People have become aware and many countrymen — many intellectuals, valuable people — have joined the opposition movement. I think the struggle to achieve the kind of society I have hoped for — one of national reconciliation, a vision that I have carried around with me for many years — is paying off and that is quite comforting.

Do you have friends and/or enemies?

I don’t consider anyone to be an enemy, though some do consider me to be their enemy. I don’t hate anyone because hate doesn’t allow you to think. As a human being I can at any given moment become infuriated and anger takes over, but I try to let it go. I have a lot of friends, people I really admire, including some whose viewpoints are different. You yourself were one of those people. We have discussed them on occasion, arguing over our ideas, but we are still friends. There are people overseas with whom I have never spoken in person but have spent years talking on the phone: economists, scholars, journalists. So I have many people to help me, who want to support me in my fight.

Your mother was Catholic. Did her beliefs have any influence on you?

My mother was Catholic and very devout but never wanted to impose her beliefs on me. My father was a communist but ended up being religious too. He left Cuba and ultimately died in New York. In his later years he completely rejected this system and died a Christian — a very, very devout Catholic. He was an intelligent man. Even when he was a communist, he enrolled me in a Methodist elementary school — the Elizabeth Bowman, which was run by American missionaries — of which I have very fond memories. Even before he was a believer, he encouraged me to study the Bible because he considered it to be valuable.

Then I met other communists who felt the same way. For example, Carlos Rafael Rodriguez, who knew the Bible very well and quoted it extensively. Or Juan Marinello who on one occasion, when asked if a library were burning down, what one book would be rescue, said the bible.

As you look back on your life, is there anything you would have done differently or are you at peace?

I am at peace with everything I have done in my life. I am very proud that I always did what my conscience dictated. When I worked with Fidel Castro, I could have done what everyone else did and I would not have had any problems. I could have taken an opportunistic approach and accepted everything he said at the time.

When I lost my job in foreign affairs, I could have adapted. I had a comfortable position, signing documents on behalf of the government even though I was not a party member. I was sent as an adviser to different countries, to Granada where I met with Maurice Bishop, to North Korea where I met with Kim Il Sung. I don’t go looking for problems. But my conscience told me to do something else and it made them look at me as though I were an enemy, which brought me to where I am now.

When all is said and done, I have to thank them. All the persecution and harassment led me to understand that the Cuban situation cannot be solved with tepid reforms. What is needed is a radical change to the whole dysfunctional system that has led the nation to disaster.

I am the son of the bourgeoisie. My family had money. My mother owned a pharmaceutical company and real estate in Cienfuegos and Havana. I left all that behind and joined the revolution without any interest in material benefit. I did not join the revolution out of class interest or out of any other interest but out of a concern for social justice and sincere love for my country.

I have come to the conclusion that democracy is essential. It is a political weapon, a social weapon, an economic weapon. Democracy and freedom are essential for a nation’s development in every area. Respect for individual sovereignty within a democratic legal framework is one of the determinants for the advancement of a people. I think one of the great advantages of American society and other societies is that they have managed to maintain balance and a capacity for self-criticism across generations.

What other national historic figures have had an influence on your personal development?

There are historical personalities whom I consider to be irreplaceable figures. First of all there is Félix Varela. When one reads about him, one wonders how a man of his era could say the things he said. It’s not what he said, but when and with what insight he said them.

There is also Martí, a key figure in Cuban history, to say nothing of military and political geniuses such as Antonio Maceo y Máximo Gómez. We also cannot forget Fernando Ortiz, the third discoverer of Cuba, a cornerstone of Cuban culture, a man who rejected tempting political offers and eschewed party politics so that he could carry out his research without other commitments.

There’s Juan Gualberto Gómez, a slave who became a remarkable figure. There’s Enrique José Varona… There are even figures whom we have to reconsider in light of independence. Although they made mistakes, as is the case with some who sought mere autonomy, they played an important role in the formation of the national consciousness by cleverly using the limited freedoms granted by the Spanish government to create conditions that would later allow those who sought independence to show that there was no alternative other than complete separation from Spain.

These include Jorge Mañach and Ramiro Guerra, whose book Sugar and the Population of the Antilles is one of the most important treatises to have been published in Cuba. The list of extraordinary men that our small island has produced is enormous.

Is there anything you would like to add?

I believe that what really matters is what one says. That’s what I can say.

From Diario de Cuba

13 December 2013