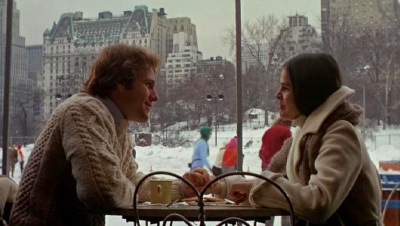

We both fell in love at the same time with the same girl, who wasn’t my mother, in front of an Elektron-216 black-and-white TV, on an afternoon in the seventies in Lawton, another of those lost words that no one in the world would think are Cuba, except Cubans.

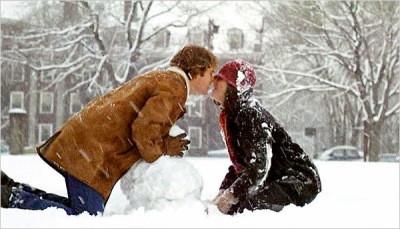

She died on screen, Jennifer. But before, she ran with him, Oliver, through the unknown streets of a miracle called The United States. And they both were beautiful and free like love, and so tender and irascible, immortals. And they ate snow and threw snowballs at each other’s heads. And neither of them had ever heard of Fidel or the Revolution.

My father had just retired. He’s been a gray bureaucrat in a nationalized industry dealing with the importing of polymers. Of the Lili Dolls of Havana Plastics. His successive offices, like his checked shirts, smelled of nicotine and that salvific smile that didn’t belong for a single minute to his environment.

I’ve said before that he was called Dionisio Manuel, but if now and again I don’t repeat his double name, we run the risk that it will disappear before its time from my memory of late exile, of fugitive props, gossiping in the face of totalitarianism itself only to take refuge in sight of those snowy mansions and hockey stadiums and phrases Made in English, in a country that wasn’t so much a homeland, but rather an open space in which to die meekly in front of strangers without the least fuss.

American movies were our consolation against Communism. Our rope made of sheets to climb down from heaven. I was the son of his old age (when I was born he was 53). He saved for me, intact, his collection from the fifties of Life, National Geographic, Reader’s Digest, and a huge maze of pocket-books which my father apparently stole, one by one, from the Jose Marti National Library (picket-books).

These books and magazines, this dead language called English, were our secret promise that there would be a survival, a future without fidelities, a history without hypocrisy, a no-place where we would both fall in love with the same girl, who wasn’t my mother, but nor was she inside the Elektron-216 black-and-white TV, but rather in an illusion of the phonetic fossil called The United States.

Well, I came here now. I have run among the hockey stadiums. I have laughed along the rivers. I have eaten snow (another way to eat the white, the trash, the emptiness). I have, I as well, a love to run with toward the abyss, with political death stepping on our heels and our parents.

For Dionisio Manuel time ran out long before B2 5-year multiple-entry visas to the USA, which now are not denied to anyone in Havana, except my mother, who in any event at age 78 will no longer have much of a girl for someone to fall in love with.

It’s Father’s Day and I am doubly orphaned. And happy. Fundamentally happy.

Even Sundays, bit by bit, begin to resemble the Sundays of our indigent infant imaginations. Hopefully, soon we’ll both be free and beautiful and tender and irascible and immortal and never will have heard of Fidel or the Revolution.

15 June 2014