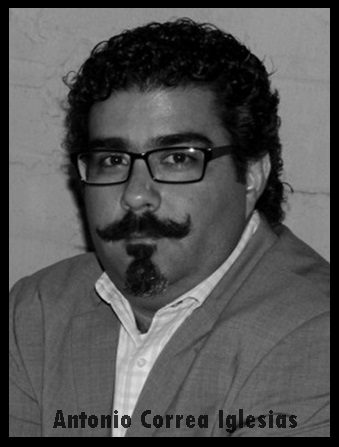

Yoani Sánchez, Madrid, 15 July 2014 – During my conversation with the writer and Nobel Prize Winner in Literature Mario Vargas Llosa in his home in Madrid, we spoke about his passion for Cuba and his disappointment with the revolutionary myth, as we reflected yesterday in the first part of this interview. Today I share with our readers the rest of this dialogue, centered on democracy, literature and Latin America.

When I was young, Latin America was a set of dictatorships and the democracies, such as Chile and Costa Rica, were really the exception to the rule. That has changed radically today, there are virtually no military dictatorships. There is one dictatorship, which is Cuba, one quasi-dictatorship, which is Venezuela, and beyond that some democracies that are far from perfect. There are varying degrees of quality and there are some Latin American democracies that are very basic and others that are more advanced. However, the democratic trend predominates over the authoritarian tradition that was so strong in our peoples. continue reading

My impression is that this is not coincidental, it’s because there is a much much wider consensus about democracy than in the past. There is a rightwing that has accepted that democracy is preferable to dictatorship, that offers more institutional guarantees for property and for business. We also have a leftwing that wasn’t democratic either, that has accepted—or resigned itself—to democracy. Which explains cases like Uruguay, where a very extreme left took power, and yet, the democratic way works, freedom of expression works, and the economy and the market work.

This also explains the phenomenon of the Concertación (Concentration) in Chile, which respected the precepts of democracy and didn’t change the political economy of the dictatorship, because it gave good results. The Concertación respected this model but expanded economic freedom and political freedom, which brought Chileans an extraordinary period of prosperity and calm.

This trend toward democracy will continue, with ups and downs, but it’s difficult to imagine there will be a reversal that reestablishes the authoritarian tradition that was so catastrophic for Latin America.

Question: How do you see the case of Peru?

Answer: Peruvians have had many dictatorships throughout our history. If I weigh it from my birth to today, we’ve probably experienced more dictatorships than democratic governments. Perhaps the greatest difference is that the last dictatorships we’ve had, from General Velasco Alvarado’s to Alberto Fukimori’s, had such catastrophic consequences that a part of the population has somehow been vaccinated against the idea that a dictatorship is more efficient for bringing economic prosperity or for achieving social justice.

We have experienced dictatorships of the right and left that have brought widespread corruption or an atrocious impoverishment of the country, like during the Velasco era, which was a leftist military dictatorship, or during the first term of Alan Garcia, which wasn’t a dictatorship but it was a populist government which, with its nationalizations and its defiance of all the international organizations brutally impoverished the country. Finally, Fujimori’s dictatorship was probably the one that was most thieving. An investigation by the Ombudsman calculated that more or less six billion dollars was stolen and sent abroad by the Fujimoro regime. For a poor country like Peru, that’s significant.

All this was so disconcerting; as of 2000 there hadn’t been a consensus in Peru for political democracy and economic freedom. There had been a consensus for democracy at some times, but there had never been one for economic freedom. Today, for the first time, there is. That consensus has brought 15 years that are so good, so prosperous, that my hope is that it lasts until its irreversible. Although the truth is that nothing is irreversible, as modern history has demonstrated.

“Literature was an indirect way of resisting the authority of my father doing something he hated and that he wanted to eliminate from my life”

Question: In the foreword to a book of poems for children written by José Martí, he said “Son, scared of everything, I take refuge in you.” In your case, were you so scared of reality you looked for refuge in literature?

Answer: Yes, literature was my refuge when I was a kid, when I met my father with whom I had a very difficult relationship. I met him when I was 11 and he was a very authoritarian person who practically isolated me from my maternal family, with whom I’d lived in a virtual “paradise.” My father was very hostile to my literary ambition. As soon as he discovered it, he thought it was a terrible failure in my life. I owe him many things: discovering the fear and discovering the hatred of authoritarianism that he embodied. My father’s hostility to my literary vocation made me cling to this vocation and I found a refuge in literature, a different way of living that life of fear I had in my parents’ house, because of my father.

I see that now, at that time I didn’t see it. Literature was an indirect way of resisting the authority of my father doing something he hated and that he wanted to eliminate from my life. Writing became something more important, more transcendent, more intimate than it had been. Until then, it was a kind of game that my mother’s family celebrated in me. With my father it was a risk to write poems and “little stories,” but at the same time it was a way of defending the freedom and the autonomy that I lost when faced with him.

Yes, in my youth literature was a refuge, but in my life literature has been much more than this. In literature we can live what we can’t experience in our own lives. We are beings endowed with imagination and desires, those eternal dissatisfactions because life never gives anyone everything they desire. We want lives more diverse, rich and intense than those we have. That is why we have invented literature, why we have fiction, to compensate for how limited our lives are.

So literature is a refuge, but it also has the ability to complete those incomplete lives we are obliged to have. However, literature is much more than that, because while it appeases that appetite for different experiences, it sparks, sparks the need, which results in greater dissatisfaction. If we read a lot it turns us into beings deeply dissatisfied with the world as it is. Nothing is better than good literature to make us discover, in such a vivid, persuasive way, that the world works badly and that it’s not enough to satisfy human aspirations/

“That is why we have invented literature, why we have fiction, to compensate for how limited our lives are.”

When you finish reading a great novel, like The Kingdom of this World, by Alejo Carpentier, or One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez, or a story by Jorge Luis Borges, what do you discover? That reality is very poor compared with that wonderful reality you’ve experienced with this fantasy, this language. This makes us dissatisfied and rebellious people, who want the world to be better than it is, and this is the engine of progress.

The world has been evolving, we have come out of the caves and we’ve reached the stars. Literature is an extraordinary stimulus for dissatisfaction and rebellion, and also a permanent critique of what exists. If this criticism and dissatisfaction didn’t exist, literature wouldn’t exist.

Question: So literature is to blame for so much dissatisfaction?

Answer: I think so, and the best proof of that is that all the regimes that have tried to control life from the cradle to the grave, the first thing they’ve done is to try to control literary creation. They try to subjugate fiction, because they have seen the danger in the free creativity that fiction signifies. Religious dictatorships, ideological dictatorships, military dictatorships… the first thing they do is establish systems of censorship. I don’t think they’re wrong, because in some ways literature is a source of sedition, discrete and indirect, but a source of sedition.

Question: You chair the Fundación Internacional para la Libertad (FIL) [International Foundation for Freedom]. How do you evaluate the work of the foundation? Do you think you’ve wasted your time?

Answer: I don’t know if it’s had the effect we wanted it to have. The fact that it exists, it’s been twelve years, we’ve had a lot of conferences, seminars, spreading liberal ideas. We defend democracy, but within democracy we defend the liberal doctrine, against which there are many prejudices. Even the word liberal has been demonized and that is a great victory for the more dogmatic left, having turned the word “liberal” into a bad word, associating it with exploitation, injustice, dictatorship.

The task of the International Foundation for Freedom is to combat this demonization of the liberal doctrine and to spread the culture that has brought these major reforms and changes to society since the creation of democracy, of the idea of Human Rights, of the idea of the individual as the pillar of society, endowed with rights and duties that must be respected and exercised freely. Those are the kind of ideas that we want to spread and to what extent we have succeeded? We have done something and I think it would be worse if we hadn’t done the things we’ve done, even if they are insufficient.