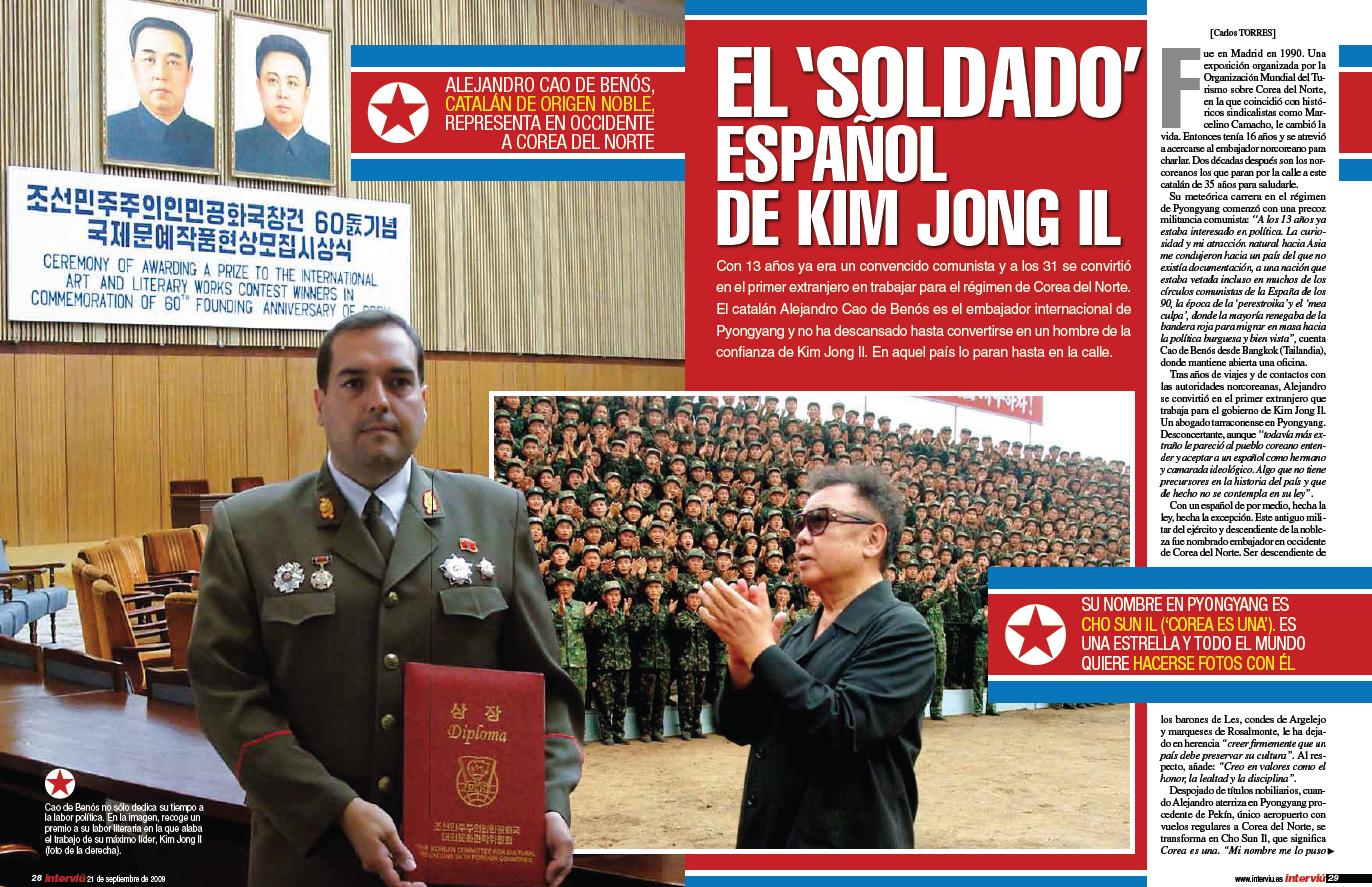

Creating a novel character based on his profile would be relatively simple. His birth name is Alejandro Cao de Benós, his adopted name is Cho Son-il (Korean for “Korea is one”), and he boasts the disconcerting title of Honorary Special Delegate of North Korea, which means that this Catalan with aristocratic roots is the official spokesman of North Korea abroad.

But his duties extend a little further.

His defense at all costs of the Kim dynasty since the beginning of the nineties and his solid and imperturbable activism outside the peninsula have earned Alejandro Cao de Benós the absolute confidence of the recently deceased dictator Kim Jong-il, such that he has ended up setting himself up as a kind of supreme national censor, to the point of deciding what information is transmitted from North Korea out to the world, and vice versa.

We are talking — as he himself has said in his own words — about the only Westerner to belong to the all-powerful inner circle of the most isolated and ferocious country in the world today.

This telephone interview, agreed to after the death of the “Dear Leader” (as all North Korea is obliged to call the late Kim Jong-il), hardly lasted twenty minutes. Mr Alejandro Cao de Benós answered my questions with a great deal of aptitude, although sometimes I wondered if he was responding to mine or someone else’s. At times his words did not even touch on the caustic issues which I was trying to investigate.

In any event it was, without a doubt, one of the most delightful interviews I have done to date. The martial tone of the dedicated Communist enamored of an ideology, his astonishing arguments explaining concisely why North Korea needs the atomic bomb more than food, provided me with twenty minutes of true journalistic surrealism with the man who, when he learned of the death of Kim Jong-il, confessed that it was like losing a father.

Hours after North Korean television announced the “terrible and irreparable” loss of the Dear Leader, a new leader appeared on the horizon. A 28-year-old leader baptized shortly earlier as “Brilliant Comrade”, unfamiliar even to many members of the innermost elite. I am speaking of Kim Jong-un, youngest child of Kim Jong-il.

Ernesto Morales: Mr Cao de Benós, how is it possible that Kim Jong-un, a young man of 28 years of age whom not even you know, as you have hinted in other interviews, is henceforth the leader of 24 million people who did not elect him?

Alejandro Cao de Benós: It’s not quite like that. Comrade Kim Jong-un has a military position, is currently vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, and has not been named leader. What’s happening is that he has received military instruction and is well loved by the Army, and there are many among the Korean people who are lending him their support and gathering around him.

That doesn’t mean that he will have absolute power over the Army or the country. That has never happened in North Korea. At present the leader depends on Mr Kim Yong-nam*, who is the President of the Supreme People’s Assembly. So we say: it is the hope of the Korean people that General Kim Jong-un continues the legacy of his father, General Kim Jong-il, but this doesn’t mean that he will make all the decisions or that he is in charge of the country right now.

In May 2001 the Dear Leader’s first-born son, and until then the clear heir of the dynasty, Kim Jong-nam, was arrested at Narita International Airport, in Tokyo. He was traveling on a false passport from the Dominican Republic, using a Chinese alias, and planning to visit Tokyo Disneyland. After spending a few days under arrest he was deported to China. The incident caused a diplomatic earthquake among North Korea, China, and Japan, and forced a shamed Kim Jong-il to cancel a trip to Beijing.

EM: Mr Cao de Benós, we understood that the first-born son, Kim Jong-nam, who you tell me will get the title of president, had lost the favor of Kim Jong-il, due to an attempt to illegally enter Japan in order to visit Disneyland…

ACB: Well, I am telling you that that information is totally false. What’s more, the Western press is creating a so-called Kim Jong-nam who doesn’t exist, who is this fat gentleman who appears on television, and who is in fact an actor paid by Japan. This man has nothing to do with North Korea.

Domestic and international tourism do not exist in North Korea. Nobody enters the country freely, and nobody freely leaves it. Not for any reason. In South Africa in 2010, North Korea took part in the FIFA World Cup for the first time. During the game against Brazil, attention was drawn to a large group of fans euphorically cheering on the North Korean team. Later it was discovered that they were Chinese volunteers hired by China Sports Management on the request of the North Korean Sports Committee.

EM: So as it seems, Mr Cao de Benós, there is a very important factor in all of this, and it is the disinformation factor. I have read interviews in which you expressly state that one of the critiques the North Korean government could make of itself is that it doesn’t pay due attention to international relations, and especially with regard to the media. Now, you decide to a large extent what information comes out of and into North Korea.

Why can’t North Koreans leave freely to do what you do, to defend their great country from Western slander, and why can’t the rest of the world freely enter North Korea, and in that way get rid of the disinformation?

ACB: That’s the part of the self-critique which I try to resolve from my point of view. Bear in mind that I am a sort of bridge between the Western mentality and the North Korean mentality. I may be the only person who has the perspective of both worlds and what I try to do is bring them together.

But basically what goes on is that Korea has been continuously subjected to periodic slander and insults. For Koreans, respect, politeness, is something typical of their culture and is instrumental in society. While for example in America or Europe there are other types of characters, an individualistic society, where everyone says what he likes and on many occasions simply insults other people, this is unacceptable in Korea.

So since so much of the media has published so much false news, what North Korea has done is close itself off completely from the outside world. And that may be debatable but it’s understandable. When a person is unfairly injured, what he does is not allow anyone else to come into his house.

EM: It’s very important to be precise: a government is not the owner of a country. A government should simply administer a country according to the interests of its citizens, just to highlight the distinction with respect to your metaphor about access or lack of access to a house.

Now, there is an interesting point: International organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, defectors from the North Korean government itself, regular citizens who have escaped through China, they have all persistently denounced the concentration camps and human experimentation, the elimination of almost half a million political opponents in the last four decades, the torture, the disappearances.

The question most basic to common sense is: How is it possible that all these people are lying, how is it possible that hundreds of testimonies agree, while you do not allow the world to come into the country to check what are simple falsehoods?

ACB: Well, look, speaking specifically to allowing someone to enter your house or not, first I state explicitly to you that the government of North Korea is a government of the people, which is originates from the people and serves their interests, it is not a government of oligarchs or multimillionaires, OK?

As in other nations, the people feel united, otherwise this system would not continue. Bear in mind that the other socialist countries have increased the level of capitalism, as in the case of China, but North Korea and its 24 million inhabitants follow the same destiny even now and will continue along the socialist path. If the North Koreans decided to do the same as other socialist countries and turn toward capitalism, it would be a decision of the people itself which could materialize through democracy.

And responding briefly to your question, it’s because of false and malicious propaganda such as what you mention that every day Korea hardens itself more in its position of distance from a slanderous and aggressive West.

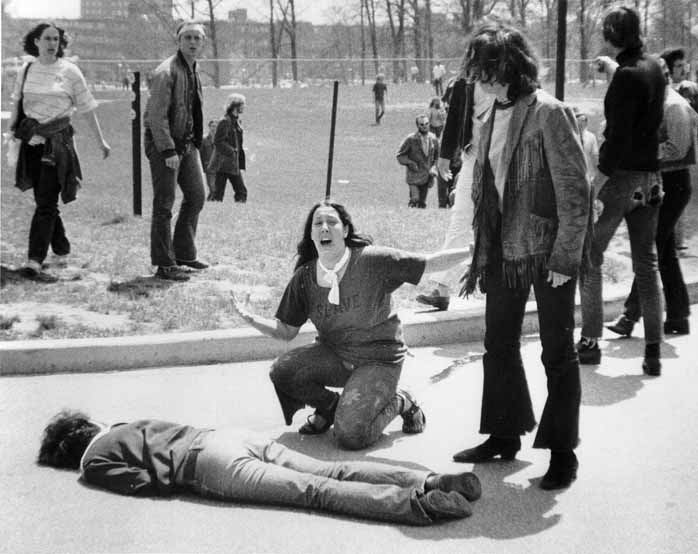

On 30 November of this year, Amnesty International reported the existence of at least six concentration camps in North Korea which hold more than 200,000 political prisoners. The largest of them, Yodok, imprisons around 50,000 people, including women and children. A report from 2006, commissioned by among others recently deceased former Czech president Václav Havel and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel, revealed chilling statistics: more than 400,000 people dead in North Korean prisons in the last 30 years.

EM: So according to you there exists the concrete possibility of exercising a democratic opposition inside North Korea. Let’s suppose that I am a North Korean and I don’t approve of what’s happening in my country. Is there a viable possibility that I can express this publicly without anything bad happening to me?

ACB: Of course, just as in any other country in the world.

But really what I mean is that if anyone goes and sets foot in North Korea and meets North Koreans, he will realize that the government’s ideology springs from a popular basis. And what’s more, those organizations which have so much to say about North Korea, many of them have never set foot in the country, and if they continue to defame it, well, Korea will be much less inclined to invite them, because all they’re doing is attacking the country before getting to know it.

If I go into a country with prejudices, thinking I’m only going to encounter what I have read or the lies I have been told, then of course I won’t be able to understand that country.

EM: Mr Cao de Benós, we have seen reports, documentaries, even ones in which you appear, in which visitors and journalists are not allowed to freely ask questions of people in the street, to film North Koreans or talk with them, without your directing and dictating what segment of the population can be visited, which areas can be filmed and which ones not. And I have seen you specifically saying with all your authority: “You can’t film that.” How is this explained from a democratic perspective? Under what precept do you think that is appropriate for a country with freedoms?

ACB: Well, look, it’s very simple. That happened because the people whom I myself have brought (I deal with hundreds of journalists from every country in the world) sometimes come to inform but others come to make trouble. They come to defame.

So if a person who comes with a camera, and has entered the country thanks to my arrangements, and for whom I have arranged the visa, then arrives in the country and what he does is make trouble, break the law, logically I am not going to give him more leeway or more opportunities to keep causing damage, especially since I am responsible because that person has entered due to the confidence of our government in me.

There are other journalists who have had more access to the country, and it depends on the level of trust I have with them. Depending on how they behave, Korea responds to them accordingly.

EM: So filming an area which is not a military zone, filming a park or a town which you or the North Korean authorities don’t want filmed, is breaking the law…

ACB: It’s not quite like that. I’ll give you an example. I have lived and worked in the United States. In fact I was in the part of California, in one of the places with one of the highest costs of living. I was working there because in my original profession I was an I.T. consultant. When I was in Palo Alto, with, of course, the mansions and millionaires who live there, I realized that after 7 p.m., when the sun goes down, all the people who lived on the street came out, the homeless, the war veterans, the impoverished masses and the drug addicts.

So, if I take a camera and film San Francisco during that time and only shoot those types of people, and I say that “this is San Francisco”, obviously that’s a distortion intended to give a poor image of that area…

EM: That’s true, but there’s a difference, Mr Cao de Benós: in San Francisco nobody is going to stop you from filming in complete freedom. And if anyone does, you can sue that person because he would be breaking the law. The law in this country is not “you can film here, but not there”. The law in a democracy is that there cannot exist someone with your authority, to determine what can be asked, photographed, or filmed, and what can’t.

ACB: That’s not the case. Every country has guidelines with respect to the media, and besides you can’t produce any show, either in the U.S. or in Spain, without a press authorization, and without press credentials.

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

EM: No, that’s not true. Nobody in the United States needs press credentials for those purposes.

ACB: Look, it even happens here in Spain. I’m telling you because I know all the journalists here. You can’t be filming the Ramblas in Barcelona with a camera without the needed authorization.

But look, all the same I’m not going to go into, I don’t have to go into such concrete details and talk about my very long experience with the media or the press, but I’ll just tell you that although you’re completely free to go all over the U.S., most people don’t go out into the street after 7:30 at night for fear of being assaulted. And besides if you don’t have a car, poor you, because it happened to me, not having a car in the U.S., having to resort to public transportation, and truly feeling afraid due to the urban insecurity you live through where you are.

Natural disasters and insane economic management destroyed the North Korean economy in the middle of the 1990s. According to estimates, the famine which then ravaged the country caused around two million deaths. In 1998 Doctors Without Borders reported cases of cannibalism among North Korean peasants, as the only way to overcome their hunger. Nevertheless, North Korea is one of just nine countries in the world which possess atomic weapons and boasts the fourth largest army in the world with 1.2 million men under arms.

EM: One last question, Mr Cao de Benós. It is well known in the world — I don’t know if you’re going to deny this too — that North Korea has a sizeable food shortage. In the past you have explained that this is simply the result of natural disasters which have ruined the fields.

All right, how is it possible that this can happen in a country which has nuclear weapons, which directs uncommon amounts of money to sustain the fourth largest army in the world, while people don’t have anything to eat?

ACB: Well look, it is explained in the following way: the main problem in North Korea is that if we don’t defend it from an empire like the United States, which has already destroyed several countries, Iraq, Afghanistan, and recently Libya, if we don’t truly defend the country, it would lose all its museums, all its culture, and would end up basically being a wasteland.

In other words, if there’s no way to defend the country, its schools, its hospitals, its education, and any advances that have been made in the last fifty years would all be lost.

North Korea knew perfectly well that Bush reserved the right to launch a preemptive attack. We also knew that since 1994 Clinton had plans to attack North Korea, and if in fact that empire held back it was because we demonstrated that we had nuclear capacity.

So I tell you that since 1994 the United States has clearly wished to launch preemptive attacks, and if we didn’t have a large army it wouldn’t matter if we built hospitals, it wouldn’t matter if we had better tractors for farming, because they would all be annihilated by American bombers.

Therefore, now that we have ensured the strength of the country, now that we know the United States won’t attack us because we have a nuclear guarantee, we can develop the economy and develop the standard of living of the people to the needed extent.

(Special thanks to Dr Vilma Petrash for arranging this interview.)

Translated by: Adam Cooper

[*Translator’s note: The blogger spelled the name of Kim Yong-nam, President of the Supreme People’s Assembly, as Kim Jong-nam, the name of the eldest son of Kim Jong-il; this has been corrected.]

December 27 2011

Left: CR7: The moniker given to the sophisticated Portuguese striker of Real Madrid

Left: CR7: The moniker given to the sophisticated Portuguese striker of Real Madrid Right: Messi “the Flea”: Golden Ball in 2009 and 2010 and the FIFA World Player in 2009 and 2010

Right: Messi “the Flea”: Golden Ball in 2009 and 2010 and the FIFA World Player in 2009 and 2010

It is, without a doubt, the news-of-the-day for Cuba. It has been news on the Island and off the Island.

It is, without a doubt, the news-of-the-day for Cuba. It has been news on the Island and off the Island. That’s not the case. They were, at all times, agents who, from the very beginning, were enemies of those opponents, men who had one very clear agenda: take notes, look for weaknesses, deficiencies and imperfections as in any human endeavor, whatever they could find.

That’s not the case. They were, at all times, agents who, from the very beginning, were enemies of those opponents, men who had one very clear agenda: take notes, look for weaknesses, deficiencies and imperfections as in any human endeavor, whatever they could find. Mr. Moisés didn’t know even one, one dignified example, at least one pearl among so many swine? Then one of two things: either the gentleman didn’t, in fact, know all the dissidents, and he specialized — in some inconceivable way — in contacting the most perverse, or, more likely still: he has no interest in offering a true picture of these people.

Mr. Moisés didn’t know even one, one dignified example, at least one pearl among so many swine? Then one of two things: either the gentleman didn’t, in fact, know all the dissidents, and he specialized — in some inconceivable way — in contacting the most perverse, or, more likely still: he has no interest in offering a true picture of these people. First: it’s impossible, in the literal sense, that any radio station or media outlet in any part of the world can immediately confirm any denunciations coming from our country. The fact that Cuba has squashed all possibilities of free-flowing information, the only options left are to either believe or not believe in those who give their testimonies.

First: it’s impossible, in the literal sense, that any radio station or media outlet in any part of the world can immediately confirm any denunciations coming from our country. The fact that Cuba has squashed all possibilities of free-flowing information, the only options left are to either believe or not believe in those who give their testimonies. Talking about Cuban doctors today brings to mind a new kind of slavery, of sad pieces used on a chessboard. Through misfortune, the doctor Oscar Elías Biscet — a free man in the damp shadow of his cell — is hardly alone.

Talking about Cuban doctors today brings to mind a new kind of slavery, of sad pieces used on a chessboard. Through misfortune, the doctor Oscar Elías Biscet — a free man in the damp shadow of his cell — is hardly alone.