A terrible phrase summarizes the maxim: “Within you, a voice exclaims: ‘My God!’. But its time to work. Deal with the rest later.” The phrase is from Kevin Carter, author of one of the most famous and controversial photographs in the history of the genre: that in which a vulture stalks the agony of one who, it later became known, bore the name Kong Kyong, who was a boy, not a girl as was thought, and who despite the famine that ended thousands of lives in Sudan, survived.

The photograph got two things for Kevin Carter: First, the Pulitzer Prize of 1994. Second: the merciless vilification by those who went as far as to accuse him of being the second vulture, for capturing the image instead of helping the dying child.

Carter took his own life a year later. His acquaintances affirm that it was not exclusively because of the media bombardment that he received as a result of his photo, the accusations of being evil and callow, but also emotional disorders that had always traveled with him

Kevin Carter’s case is the most notable case. Unfortunately it is not unique.

In 1985. the Colombian volcano Nevado del Ruiz erupted and took the lives of more than 25 thousand people.

The photojournalist Fran Fournier documented the disaster in Colombia with a meticulousness that chilled the bones. But he did something more: he aimed his lens at the precise angle required to turn a scene into History: the girl Omayra Sanchez clinging for dear life, holding on to a tree branch, while she struggled to escape being swallowed by the tide of mud and quicksand.

The image is painful by itself. To know that the attempt by rescue workers to save her did not bear fruit, and the girl died, transformed the photo into a heart rending testimony. And its author, for many, into an immoral character.

Fournier was not Kevin Carter: he did not take his life, and was able to struggle against the accusations of those who berated him as a cruel opportunist, even if, at the instant when he pressed the shutter, it still looked possible to save the valuable life of Omayra Sanchez. But his snapshot placed him in the center of an ethical-moral debate that is not over to this day.

These examples by themselves would fill a volume with the names of the slandered, both of the photographers who filmed scenes that may have been avoidable if they had left their equipment sitting on the ground, and of the journalists who narrated live an execrable event of which they were the immediate witnesses.

Tough profession. Tough inner conflict for those who, obeying the maxim to spread truths, realities, facts, keep at bay the screams of horror in their throats, and do their jobs. They click the shutter. They hold the camera steady. They narrate the facts for all to hear. They remember that through their eyes, their voices, their lenses, the world will find out what is happening. And they do not care what comes later. “Deal with the rest later,” as one who could not do it would say.

True journalism, that which respects itself, that which responds to iron precepts, the same way that medicine bends to its Hippocratic oath; journalism that knows who it works for: those who otherwise wouldn’t know that things like this happen in far away places, is without a doubt one of the most necessary professions among all that exist, and honestly, one that receives one of the worst shares of gratitude in return.

When Kevin Carter was horrifying a well-fed world with that image, when he was improving the angle and the position of the light instead of waving the buzzard away, he was doing something more important than saving that life: he was saving, perhaps, tens of thousands. There was no better way to denounce the Sudanese tragedy than to grate on the nerves and sensitivities of the world with such a scene.

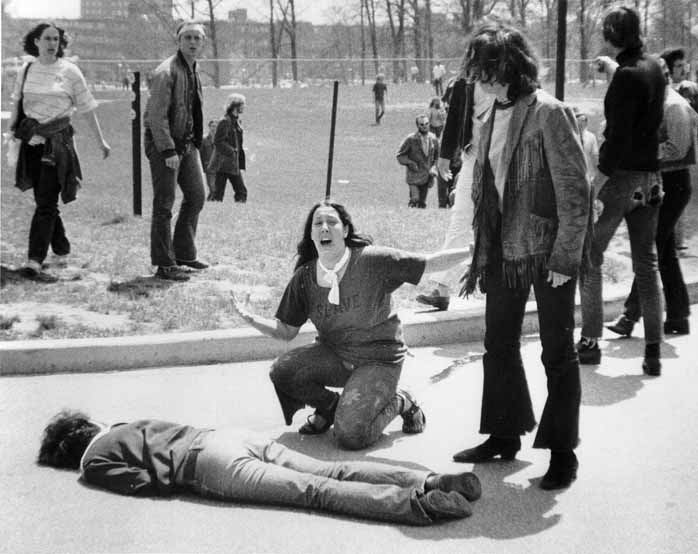

When John Paul Filo captured the choleric scream and pain of that young woman before one of the victims at Kent State, shot miserably by the National Guard while they protested the war in Vietnam, instead of succoring the bullet-ridden, he was doing something that perhaps no one else could have done: pinning the image on the historical memory of that country so that crimes such as these, violations of freedom of expression such as this, would not happen ever again.

There is a reason why dictatorial regimes, satraps the world over, those who love doing and undoing to their heart’s content, eject or jail authentic journalists.

There is a reason that some of the best exponents of this Fourth Power have paid with their lives for the arrogance of shouting with no limits about what was happening in Pinochet’s dungeons, what is happening in the narco-violence infected streets of Mexico or in the human experimentation laboratories in North Korea.

Too many responsible for not allowing crimes to exist with impunity, violations without denunciation, catastrophic events without aid, left this world not receiving in return the most deserved prize that humanity can bestow: gratitude. It is not too late to think about them, those who, between bombs in Afghanistan, dangerous conflicts in Libya, Syria and Egypt; those who amid savage butchery in Mexico or cruel state repression Cuban, Venezuelan or Ecuadorian style, commit their lives to tell the facts, to spread the word.

Translated by: lapizcero

October 24 2011