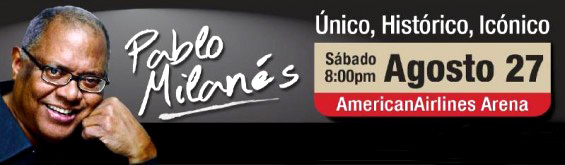

On August 27th, Pablo Milanes will sing in Miami. According to the billboard ads, it will be a historic concert. Of course it will: for his followers as well as for the Vigilia Mambisa. Some will lose their voices for singing along to his songs; others, outside American Airlines Arena, will lose theirs screaming out “communist” at him.

Without a doubt: a historic concert.

No wonder. Pablo is not just another Cuban troubadour. Pablo has been unhappily confused with Paulo FG (some protests that can already be seen in Miami exhibit banners that say: “Out Paulito Milanes”), but unlike the salsa singer, Pablo is unique, and is the other component of the most representative binomial of Cuban music during the post-revolutionary era. Silvio and Pablo: the sharp duet.

If I am tied to Silvio Rodriguez by the admiration for the sublime poetry of some of his best songs, and the absolute rejection he inspires me as a man of ideas, and further more, as a human being, with Pablito I invert those factors a bit: I fancy him more honest and worthy than the singer of the Unicorn, but his music is not as appealing to my ears. I respect it, but I don’t love it.

When I speak about inverting the factors just a bit, I am exact: Pablito Milanés, born in the same city as I, erected lately as a media critic of the Cuban Revolution, doesn’t offer me any confidence or attention as a committed artist. What’s more: I fancy him lightly opportunistic.

(One point to be clear about: to evaluate him politically is fair because he doesn’t skimp in talking about politics. José Ángel Buesa was asked in Santo Domingo about the nascent Cuban Revolution, after he traveled outside of Cuba in 1959, and he answered: “Did you ask Fulgensio Batista about poetry when he passed by here a week ago? Don’t ask me about politics.” One cannot evaluate José Ángel Buesa with a political standard. Pablo Milanés sometimes talks about his music with the foreign press.)

Why an opportunist, Dear Pablo? Simple: because screaming when they stomp on our toes is very easy. To scream without the stomp, is very different. And I don’t think I am revealing a secret when I say that the divorce between the great troubadour and Cuban officialdom has a date and almost a time: at exactly the instant when his plans for the Pablo Milanés Foundation were thwarted.

Since then, put a camera in front of him, he’ll say his thing. With success great or small, but he’ll say it. It is possible that all of a sudden he’ll throw out ideas like the Revolution will continue after the death of Fidel and Raul Castro, something he thinks is great; it is possible for him to affirm that Raul and Fidel truly want to repair the country they have mistreated; but he’ll also criticize the gerontocracy that governs the destinies of the country, he’ll support harsh declarations from Yoani Sanchez, and defend the talent and pose of the censured rappers, Los Aldeanos. Good for Pablo.

However, it is still a suspicious and questionable attitude for an artist to pose as politically committed to the democratization of the island, just so long as he is outside it.

Has somebody heard Pablo Milanés in Cuba confronting the regime in Cuba loud and clear, saying uncompromisingly that which he declares to the Spanish or South American media? Where was the Pablo who repeatedly gives controversial interviews in foreign countries, when 75 people were imprisoned for writing against what they saw all around them, or when three Cubans died before a firing squad for wanting to escape the country? Could it be that then he wasn’t outside Cuba and therefore, the lock on his throat did not disappear?

I adored the Pablo who invited Los Aldeanos to sing at the Havana Protestrodome itself, sticking out his tongue to the censorship that falls over this rap duo. But it seems too little to admire him like others.

So then Pablo comes to sing in Miami: I’m so glad that’s the way it is. I applaud the happiness of those who will enjoy him this coming August 27th. However, what is he doing, what has he done, and what will our Dear Pablo do to unlock a cultural exchange which he now favors, but which is a one-way exchange?

I am not talking about words in front of the amateur camera of a young filmmaker who interviews him in Havana. No. I am talking about real efforts. I am talking about demanding and fighting for the rights that his compatriots in exile possess, his co-artists, of singing in the country that watched their birth and of which they have been stripped by the grace of an exclusionary ideology. I am talking about declaring himself inside, of utilizing his concerts, of demanding in writing before all the Ministries, with a signature that it is not from just any other Cuban: it is the signature of Pablo Milanés.

Did Pablo ever defend the right of Celia Cruz to sing her songs at a plaza in Havana just as he is coming to do at the Miami Arena? Would he publicly invite Willy Chirino to collaborate with him on the Island, knowing that Willy would give a piece of his life to be able to sing in his homeland? Again and again: No.

That is why I, who defend tooth and nail the right to freedom, and therefore the right of an artist to show his work at any stage on the planet, I don’t promulgate but I do understand the claims of those who, from this side of the ocean, feel incited and indignant by the presence of Pablo Milanés, and even more: by the presence of the avalanche of Cuban artists who step on American soil today. (Of course: to then say, as does a certain character whose name I’ve always tried to forget, that Pablito is not a musician but an agent sent by Castro, goes a long way toward separating the wise from the intellectual orphans.)

Miami, let’s stop the false statements, is not just any city. Miami has been, for half a century , the oasis of victims, of the pursued, the imprisoned, the exiled from Cuba, and that cannot be disregarded when it comes time to put the circumstances in perspective. A portrait of Josef Mengele is not the same on a New York corner as it is in Jerusalem.

Personally, I will not carry any signs nor will I raise a hand to condemn the presence of my fellow countryman in this symbolic city, but the reasoning of those who will, does not seem illogical to me.

The subject is one of a tremendous moral-ethical complexity.

If it was only Pablo, the excessive emotion would all blow over a day or two after the 27th. But the reality is much more serious: turning on the TV in Miami, switching to on any Hispanic channel, has made me ask myself where I am: do I, or do I not live in Cuba?

If Ulises Toirac works at MegaTV before returning in a few months to the ICRT; if Nelson Gudín appears at the same time on the show in America Tevé before returning to Cuban Television; if Osdalgia closes, repeatedly, with her music on Alexis Valdés’ show, and Gente de Zona announces their concerts at The Place and in Las Vegas; if Alain Daniel — and this is the last straw! never before seen! — admits that this time he hasn’t come to offer any concerts, he is just going to spend a week in Miami recording and mastering his new CD; if such a notorious apologist for Fidel Castro as Cándido Fabré splutters with his phantasmagorical voice that he feels happy to be in this city; if all singers, humorists, painters or journalists who I saw in Cuba 7 months ago are the same people I see before the cameras of this country, it becomes difficult for me to situate myself in time and space.

But most of all, I find it hard to swallow that this reality is just and acceptable. I find it hard to applaud the dual speech of musicians such as La Charanga Habanera, when they sing inside of Cuba “You’re crying in Miami, and I’m partying in Havana”, and as soon as they step foot at Miami International Airport they despicably vary the chorus to please who will fill their pockets: “You party in Miami, and I party in Havana”. I find it hard to accept that those same salseros (salsa singers) and regueatoneros (reggeaton singers) who today do extremely well for themselves thanks to Miami and its audience, thanks to capitalism, to the market economy, to the country of bars and stars, are the ones who, when they return to the Island, sing at celebrations for the 26th of July and celebrate anniversaries of the same Revolution that denies the entry to so many residents of Miami. And let no one come to me with stories: my memory is only 27 years long, with 7 months of exile.

So then, what is the benefit to the exiled community from this euphemistic cultural exchange? None at all. How what does it benefit it economically? As little as possible. The beneficiaries, the only ones who profit out of the bridge that Manolín asked for in his song that in some ways now exist, are those same artists who play a dual role, an embarrassing role as cultural political supporters of the Cuban establishment, while they go to the abode of the enemy to fill their coffers.

It is not the same thing to have Frank Delgado in Miami, as Cándido Fabré. It is not the same to have Los Aldeanos, as Gente de Zona. It is not the same to have Pedro Luis Ferrer, as Pablo Milanés. The outcast among the unjust is not the same as the accomplice and the ones that were integrated into the unjust.

Morality must be very fucked up in a country that screams out slogans to the enemy, and later looks for, in silence, the enemy’s gold. My best wish for the great Pablito, the icon of the Nueva Trova, an illustrious Bayamés (someone born in Bayamo), is that he enjoy his stay in Miami, and hopefully the whispers of pain and nostalgia from the million and a half emigrants that wander about on this land, won’t overshadow his magnificent voice during his concert.

Translated by: Angelica Morales

August 1 2011