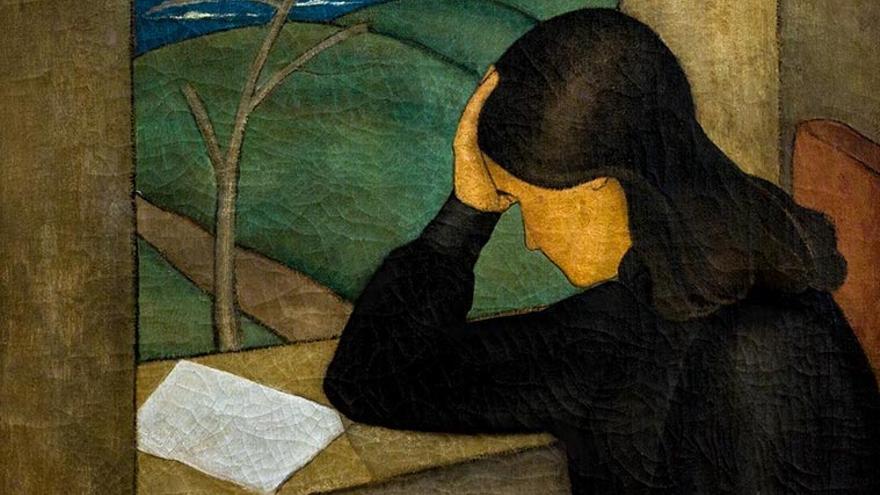

![]() Xavier Carbonell, Madrid, 25 June 2023 – In the land of Roberto Fabelo all the statues have been decapitated and the cities are in ruins. Junk, coffee pots, washbasins, cookpots, drowsy and rugged faces, letters that have forgotten what words they belong to, men who are half asleep or who sleep the sleep of reason – all these define the artist’s work.

Xavier Carbonell, Madrid, 25 June 2023 – In the land of Roberto Fabelo all the statues have been decapitated and the cities are in ruins. Junk, coffee pots, washbasins, cookpots, drowsy and rugged faces, letters that have forgotten what words they belong to, men who are half asleep or who sleep the sleep of reason – all these define the artist’s work.

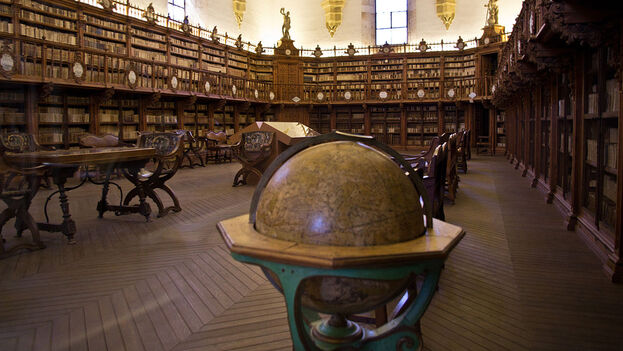

The tide has carried Fabelo’s works to Madrid and those who turn up to see them in the little red brick salon in the Condeduque arts centre, surrounded by geometry and order, don’t imagine they’re looking at something collapsed. The return of the master to Europe – he looks cold and black and older – does not come without some reflection and sadness. He comes in search of a father, a lineage that has always been his but one that he now wants to announce: Goya.

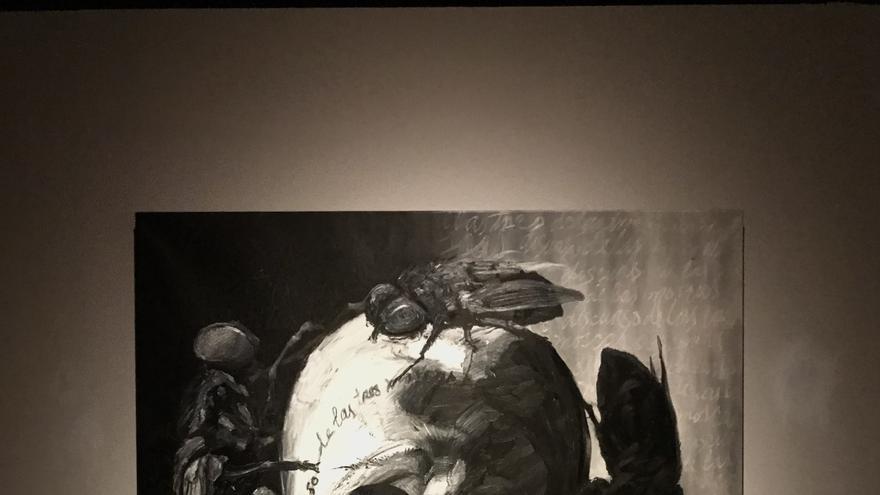

The affinity between the painter from Aragón and the Cuban one was marked from the day in which Fabelo painted his first animal with a human face. There’s a certain look that’s essential to both: the depth of the dark layers of the human, in the parts where the light upsets everything and the creatures are saturated with meaning, words and forms. Like Goya, Fabelo fills his pictures with phrases and codes. One of them promises: “if the sun comes up, we’re out of here…”; the other one paints “…on the wings of a fly”.

Anyone who has followed Fabelo’s works on his native island, where they form part of domestic life and imagination, will note the transgression imparted by Mundos [Worlds]. From having a certain affinity with the regime – at some points he has attributed his success, with timidity, to Castro’s revolution – he has moved more towards criticism, through the use of symbolism. The fraudulence of power, the manipulation, the possibility of dissent and of withdrawing from the scene, the predominance of the worst always happening – these all impose themselves on top of any other themes. continue reading

Upon entering the Condeduque centre, various Kafkaesque-style cockroaches tell the visitor that they’ve arrived in the dominion of monsters. Lined up like a battalion, they are Los Caprichos [The Caprices] and Los desastres de la guerra [Disasters of War], which make up some of Goya’s twilight works. They’ve already engaged in battle with Fabelo’s rhinoceroses and satyrs. What we witness – in the darkness of the salon held back by time – is the dialogue between two gentlemen who have shared a duel.

From this planetary confrontation, in which Fabelo spars also against other models of his – Durero, Dalí, El Bosco – emerge, unharmed, certain domestic objects, which the Cuban has always treated with kindness, like talismans. In a cauldron there is the Virgin of Kindness, patron of Cuba; the coffee pots have faces, and weep for all the shortages; bullets fired by soviet rifles on the island have become magnetised into a sphere.

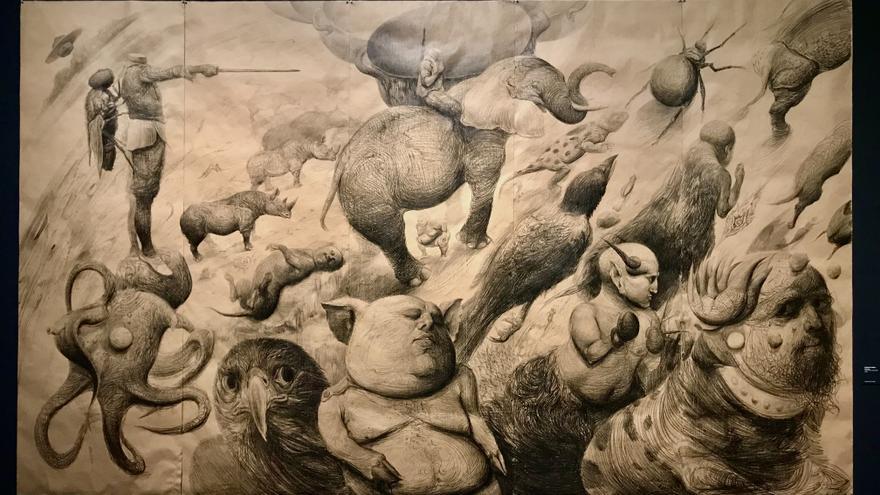

Fabela, like Goya, is an elemental narrator. He’s interested in the weight of a story, the accumulation of gestures and signs with a synthetic capacity which connects him with Monterroso or Borges. In Liderazgo, created in 2022, on an immense sheet of cardboard, Fabelo encodes, without admitting it, the drama of the island of the last two years. The stampede of animals away from a fire or a deluge; the decapitated general, sabre in hand, leaning on an octopus, still insisting on giving orders; the incredible large ugly bird; the ogre; the satyr boxer; a creepy crawly that pleasurably rubs its back against the mud; the whisper of flies – all encapsulate the drama of fleeing or of remaining in an oppressive place. A self portrait of Fabelo as a monster abandoning with fear the margins of his own picture gives us a hint as to the conflict in the life and work of the painter.

Of course, Fabelo’s calibre is encyclopaedic. His drama belongs to everyone and isn’t confined to the cartography of Cuba or of Cubans. Neither are Goya’s uniforms, swords, canon fire and vermin limited only to the Napoleonic era, all of which ask whether there isn’t anyone that can let them loose. Between both painters gravitate two centuries, annulled by the same sensibility. It’s probable that exile, memory and death, which have always pursued Fabelo, will catch up with him finally in Europe. It’s the price of immortality.

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.