![]() Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca 23, April 2023 – As winter worsened, curled up in my train seat I received a message from an old acquaintance. He was one of the librarians from my village whose wooden house with coloured roof-tiles, not far from the park, I had visited more than 15 years ago. Are you the student, he asked, to whom I gave the Encyclopaedia Britannica?

Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca 23, April 2023 – As winter worsened, curled up in my train seat I received a message from an old acquaintance. He was one of the librarians from my village whose wooden house with coloured roof-tiles, not far from the park, I had visited more than 15 years ago. Are you the student, he asked, to whom I gave the Encyclopaedia Britannica?

That was a long time ago — all the cities and the friendships lost, the time I started to smoke, university, significant relationships, the death of my grandfather, reading, discotheques and ghosts. Of course it had been me. I immediately saw myself grabbing a good bicycle, soliciting the help of some friends — only one of them came along — and heading for the librarian’s huge house.

A few weeks earlier I had stolen a Borges anthology from my school. What that volume had to offer, even just by flicking through it at random, was not something that one ever forgets: “Ireneo Funes died in 1889, from a lung infection”. And: “Our mind is porous for forgetfulness”. Or, if one played chess: “God moves the player, and the player moves the chess piece. Which God behind another God starts the game off?”

Any age is good for reading Borges, but 17 is ideal. Infancy is already just a memory; youth has only just begun. The blind man — “slow prisoner from a sleepy time” — arrives to accompany you in that rite of passage. I learnt from Borges that there was a sacred book, or more exactly a multiple of books: the Encyclopedia Britannica. The hunt for one of these, with the objective of giving it an honourary place in the bookcase, was like searching for a magical object.

Victim of a naivety that today would feel delicious, I came to believe that the Encyclopedia Britannica itself was as imaginary as Tlön, or any other one of those many made up titles that Borges alludes to and which later — as happened with The Approach to Almotásim — ended up being listed as real titles by gullible librarians.

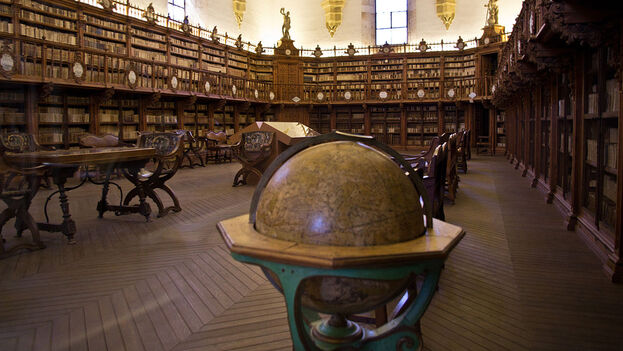

I soon learnt that not only had the volumes existed since 1768 but that several of them had arrived on the island in the forties and fifties, bought by enthusiasts of the English language. The Britannica, declared the reviews and even Borges himself, understands the universe and puts it within our own arm’s reach. Thousands of engravings, maps, diagrams and fold-outs illustrated its articles and turned any one of its volumes into a cabinet of wonders, an optimum and immeasurable inventory. No reader’s lifetime would be long enough to enable them to digest the immensity of its volumes’ knowledge.

I don’t know how I came across the woman who, without having read Borges, was the owner of the 1929 edition. She had collected in a box some twenty or more copies, all with their gilt lettering and Prussian blue covers. I examined the books: among them there was evidence of moth larvae having drilled tunnels through the paper, through all the words – written passages chewed up with the dispassion of a reader. She asked me whether, despite this, I wanted to take the box. I answered yes, knowing that she was presenting me with a time-bomb, a veritable colony of implacable enemies that, after devouring the Britannica, would continue their expeditions through the rest of my bookcase.

The moths lived off the encyclopaedia until, years later, a kind of imperial decree forced me to get it out of the house. Deciding to save at least a fragment of that kingdom, I went through hundreds of thousands of pages, one at a time, cutting out articles I couldn’t lose, along with all their relevant maps and prints. Having to mutilate a book is the worst kind of torture that a reader can be subjected to. I tore a whole encyclopaedia to bits.

As I write this — too long after that day — I am looking again at those pages that I rescued. I carried them with me from the island and they form part of my collection of lucky charms. I have, with one beautiful Egyptian engraving, the word Rosetta. I have a little album in which pictures of archways and columns adorn the definitions of words like abbey, or romanesque. Unusual words like microtomy — the art of carefully cutting up plants and animals in order to study them — and the Quixotic bascinet and the biography of a German called Knipperdollink. There are also gentlemen, all kinds of trees, monsters, explorers, little devils and uncommon alphabets.

(My encyclopaedia wasn’t a dream, and the loose pages that I still keep do reassure me in that respect. I found out later that H.G. Wells, like Borges, had given the books an additional use: as an aficionado of toy soldiers, he used the volumes in his collection as the mountains and trenches of his battlefields).

Anyone who isn’t acquainted with these books, who hasn’t held one of these blue tomes in their hands — made up of “an infinite number of infinitely slender sheets” — cannot imagine the significance of the Encyclopedia Britannica for those who, at one time or another, like young people eternally aged, were their owners. As the blind man said, in that anthology which I stole 15 years ago: “Somebody else, on some other hazy afternoon, got to own all the books, and the shade.”

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.