![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 5 June 2023 – A universe in miniature tries to survive in Cuba, despite neglect and dirt. It is the house of the Republican poet Regino E Boti (1878-1958) in Guantánamo. Poor and adrift, the only riches in the shack are the bottles of amber liquor and a battalion of chickens that let no one sleep. Its occupant, and protagonist of the film La Espera [The Wait] by Daniel Ross, is the poet’s grandson who shares both his first name and surname.

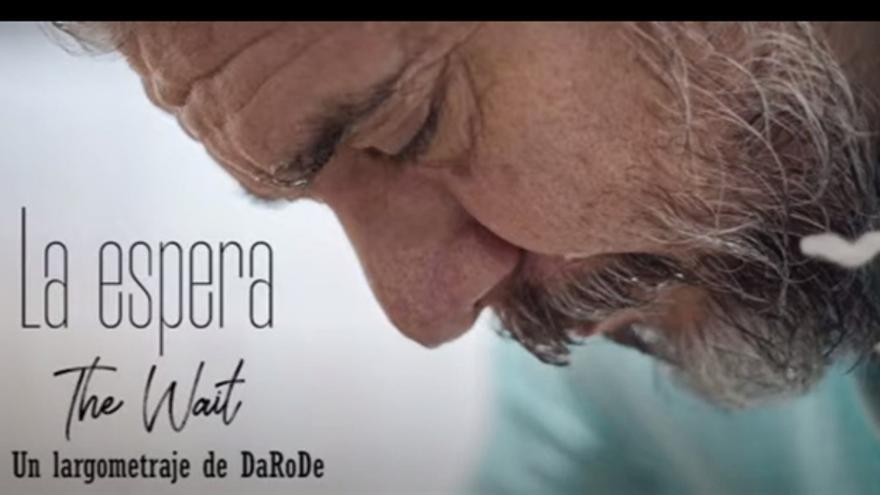

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 5 June 2023 – A universe in miniature tries to survive in Cuba, despite neglect and dirt. It is the house of the Republican poet Regino E Boti (1878-1958) in Guantánamo. Poor and adrift, the only riches in the shack are the bottles of amber liquor and a battalion of chickens that let no one sleep. Its occupant, and protagonist of the film La Espera [The Wait] by Daniel Ross, is the poet’s grandson who shares both his first name and surname.

The film, a fiction about loss and sorrow which was premiered in France last month, is based around the house itself, and Boti, who moves between its rooms like some kind of Minotaur. Bearded and unsociable, yet very noble, the man receives his few friends and offers them everything he has: sweet potatoes, eggs, alcohol and company. It’s the sole comfort that remains for him after the death of his wife, whose clothes he keeps carefully on the marriage bed, “because objects also have souls”.

His routine is stifling: wake up with a hangover, make coffee, switch on the radio – always guantanamero music – feed the animals and spend time on little artisan crafts like drawing or making models out of matches – which he later sells.

When the meditation and the silence appear to have reached a climax and Boti seems to have reached something resembling peace, a huge explosion sounds in the vicinity of his shack. These are the mines which go off outside the nearby U.S naval base whenever a Cuban tries to cross into the zone. Someone – it’s not known who – leaves the shoes of the dead on the doorstep of the house, which Boti throws up onto the flat roof like some kind of ritual.

Fortunately, after each explosion his friends arrive, also loners: Moya – a Quixotic beggar and meditation enthusiast; and a soldier from the Cuban frontier brigade who never gives his name.

Via this soldier – in love with a female soldier whom he tries to “knock over” with poetry – Boti discovers something about life in the base. The savagery in the brigade shocks him, and for this reason he agrees to look after a little dog which ran across the border and came back chubby and fit thanks to the Americans’ feeding him. It was an absurd gesture but the party leaders in Cuba then declared the animal a “traitor” and ordered it to be hunted down.

Boti clings so much to the dog’s affection, that he sees in her, if distantly, a copy of the love he had for his mother. Accustomed to seeing ghosts, the trust which the dog shows him seems to him more pure and dignified than any human behaviour. In any case, Moya – who we see for the last time naked, euphoric and gripping a rifle as he heads into the mountains – and also the soldier, both have something bestial, wild about them, and for this reason it’s easier to show them the door.

One views both the house and the naval base – as if they were living creatures – with rancour, in a country that would, if it were able, abolish the existence of both: Boti’s shack because, with its junk and hundred-year-old furniture, it reminds us that the past was better; the military buildings because they are the thorn that Fidel Castro could never remove from his heel.

Daniel Ross’s camera captures the harshness of Guantánamo, the suffocation in Boti’s mind which, in many ways he reproduces in the house itself. The director has shown that it’s more and more difficult to produce a film on the island, and that the cinema of today is just a survivor that’s moving closer to the abyss. Nontheless, the young creator overcomes the technical obstacles impeccably.

If anything should be particularly pointed out about the film, it’s rather the quality of the story, whose rhythm is more tiring than it should be and it quickly abandons some very powerful symbols and motifs. To resort excessively to fixed planes, to focus over and over on objects and landscapes, and to work less on actual dialogue, threatens the economy of the narrative. Nor was it a good idea to insist on including the final sex scenes, which end up clouding the symbolism of the absent wife – otherwise plotted subtly by means of the clothes, the dog, the glass of water and the poems.

Despite these neglected areas – and those of the performances, which, perhaps because they are course end up being endearing – ‘The Wait’ will go on to have success at international festivals and it promises to be just the start of a career in film for Daniel Ross.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.