![]() Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 21 May 2023 – On 25 April 1969, Remberto Pérez was reunited with his family in the United States after two years separation. He’d escaped from Cuba just as he’d turned fifteen – the Armed Forces were ready to call him up – and he headed for Madrid, where a Franciscan priest, Antonio Camiñas, took charge of looking after him until his parents could leave the island.

Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 21 May 2023 – On 25 April 1969, Remberto Pérez was reunited with his family in the United States after two years separation. He’d escaped from Cuba just as he’d turned fifteen – the Armed Forces were ready to call him up – and he headed for Madrid, where a Franciscan priest, Antonio Camiñas, took charge of looking after him until his parents could leave the island.

Las Tunas had become an inhospitable city for the Pérez family. His father spent long days under the hot sun in the east of the island, under constant threat of a machete, and unpaid: this was Fidel Castro’s punishment for asking permission to leave the island. His mother, after saying goodbye to her son Remberto at the airport, discovered that she’d become pregnant for the fourth time.

His sister María also remained behind, and after more than fifty years she hasn’t forgotten what those last years in Cuba meant for the family. Two years after Remberto’s departure in 1967, they all managed to emigrate to the United States.

Remberto and María had much to talk about: he had become one of the so called “children of father Camiñas” — between 1966 and 1974 the Franciscan managed to give refuge to around 4,000 minors in Spain for as long as was necessary — she had witnessed the deterioration of the country just as she had witnessed the deterioration of the family itself.

“I said goodbye to a fat little boy and met up in New York with a tall handsome youth who dressed like The Beatles”, remembers María Pérez, 69, in conversation with 14ymedio. “Nevertheless, he was shocked when he saw us. My father was very suntanned, I was very skinny and my mother wasn’t well”.

The siblings decided to tell Remberto’s and the stories of the other children – those children of what some people have named Operation Madrid – in the book Cuando salí de Cuba [When I Left Cuba] (Casa Vacía), with the collaboration of the historian Ricardo Quiza.

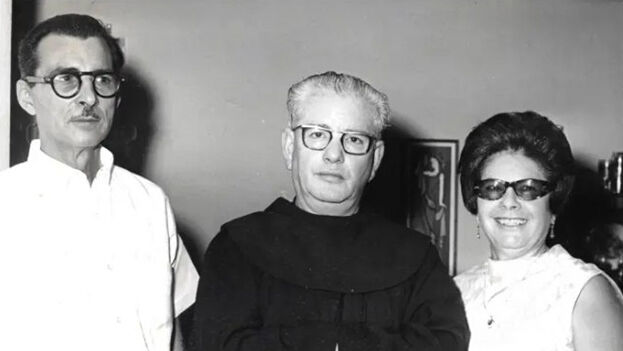

The silent protagonist of the story – which brings together 50 testimonies – is Antonio Camiñas, a priest, born in Remedios in the old province of Las Villas and expelled by Castro to Spain. For María Pérez, it is “a moving story” that has been ignored for decades by Cubans.

Camiñas arranged for the welcoming of the island’s children from the church of San Francisco el Grande in Madrid – which became his general headquarters; the minors had been on the point of being recruited into Castro’s armed forces.

“The main reason for getting the children out was the Military Service Act which required young men aged 15-27 to remain in Cuba”, Pérez explained. “However, the immediate danger were the UMAP [internment work camps for ‘undesirables’]– the military units that give support to manufacturing, because the boys were nearly all religious and from anti-establishment families, that had expressed their desire to leave the country”.

“Everyone remembers Camiñas as a kind of angel but one with his feet firmly on the ground”, he says. “He was very Cuban. They said he smoked a lot. He gave all the boys affectionate nicknames. He was also a very practical man”.

Food, clothing, medication, transport: Camiñas was an administrative genius who shared his skills with other priests and Cuban families in Spain. The children will never forget the black Cadillac owned by Isabel de Falla – a millionaire from the old Cuban nobility – which picked them up from Barajas airport. “It was like an ocean liner cruising through the streets of Madrid”, they record in their testimonies.

Camiñas, Pérez says, never wanted to publicise his work, not only out of discretion but because he considered it his mission as a religious human being. The children are grown up now but that doesn’t prevent them from “going back in time” through the retelling of the tale – to the El Escorial hostel, the Casa de Campo and Navacerrada, where Camiñas gave them shelter.

It’s the voices which are important in ‘When I left Cuba’ – a book of testimony, not a history book. It will fall to more studious writers, says Pérez, to explain some of the deeper questions surrounding Operation Madrid, such as: how did Camiñas manage to avoid Castro interfering in his plans? Was there some secret agreement between the regime and Francisco Franco, the Spanish dictator who died not many years later in 1975? Why did Cuban propagandists decide to hide the childrens’ story instead of using it to discredit those who chose exile, as it did with Operation Peter Pan, in 1960?

“The objective of the book is to open up a window to such questions”, admits Pérez. Not even the families involved are sure where the plan came from. In Cuba in 1966 they began to talk about that “route” for getting the children to Spain. You had to go to the embassy, obtain the documents and pay for the passage.

“It cost me a lot to think that the Cuban government wasn’t in agreement with the Spanish one. Nearly 4,000 children couldn’t leave a country without the regime knowing”, he reflects. Spain and Cuba, he adds, never broke off relations and Castro had a certain kind of friendship with Franco, of whom he said that “he never treated his government badly”.

At first it was a bit disorganised, says the co-author of ‘When I left Cuba’ – for example, the case of the boy who arrived at Barajas but there was no one there to pick him up. “A police officer spoke to him and took him to an office where, by chance, they knew about Camiñas’s work. One of the officials took him home and he stayed there until he was taken to the priest a day or two after”, he says.

In another case a boy of 11 was taken in a bus directly to the church of San Francisco el Grande. “Because of these situations Camiñas began to organise daily visits to the airport to see whether there had been any children who arrived unaccompanied. There were many people who helped him”, he explains.

At the Escorial and the other hostels the children lived out their adolescence as fully as circumstances allowed. They collected pesetas to travel into Madrid for walks, went on tourist trails, were well liked by everyone and talked nonstop. “They cried during the night; in the morning they got up to play ball”, says Pérez. “Of the ones that I know, none blamed their parents for the decision that they made”.

Eventually the time came to tell the whole story. Remberto came home and said to his sister: “Oskar Schindler saved hundreds of Jews from the Holocaust and the whole world knows about it. But father Camiñas saved nearly 4,000 Cuban children and today no one remembers who he was”.

María’s first idea was to approach the writer Enrique del Risco, who couldn’t take on the project but recommended Ricardo Quiza as a collaborator. The process took two years, during which dozens of “children” were interviewed. “It’s all recorded”, Pérez assures us, thinking about a possible audiovisual future for the project.

After seeing the results and the reception of ‘When I left Cuba’, both Pérez siblings are convinced that it will get harder and harder for the regime to hide the story of Operation Madrid. “My parents were sure of one thing: they wanted to save their children. I believe that they did”, says María, whose memory “beats and goes on beating” for the island – as it goes in the song by Luis Aguilé which gave its title to the book.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.