![]() 14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 7 May 2023 – I re-read Dulce María Loynaz, I listen to recordings of her voice, I submerge myself in her world. I see her descending to the lounge of her house in an iron elevator. She opens the grille and exits, fanning herself, passing between the armchairs and yellowing sculptures. She recites what may have been a monologue from ancient tragedy: “I live alone, I have no children. I lost my husband, I lost my brothers. I’m not afraid of anything — imagine! I am the daughter of a soldier. The daughters of soldiers are not afraid and neither should they be”.

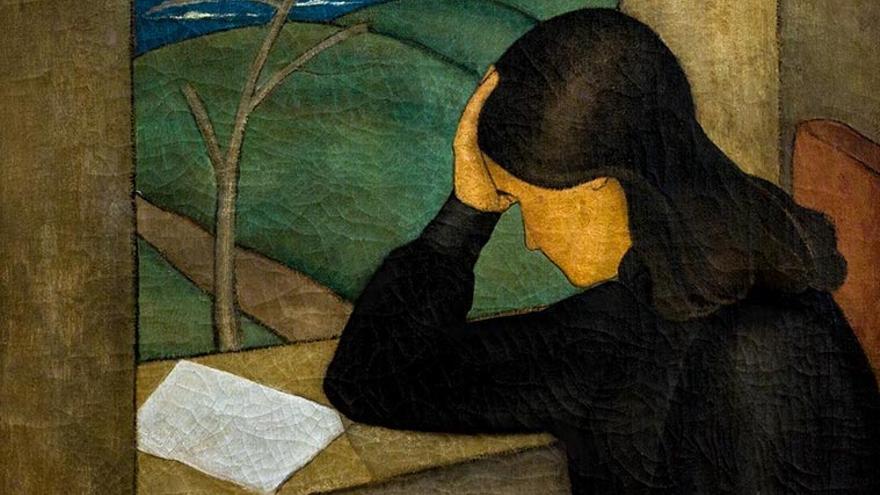

14ymedio, Xavier Carbonell, Salamanca, 7 May 2023 – I re-read Dulce María Loynaz, I listen to recordings of her voice, I submerge myself in her world. I see her descending to the lounge of her house in an iron elevator. She opens the grille and exits, fanning herself, passing between the armchairs and yellowing sculptures. She recites what may have been a monologue from ancient tragedy: “I live alone, I have no children. I lost my husband, I lost my brothers. I’m not afraid of anything — imagine! I am the daughter of a soldier. The daughters of soldiers are not afraid and neither should they be”.

Her life, which spanned a whole century, took her from Havana to Ankara, and later to Damascus, Tripoli, Cairo, New York, Mexico, Salamanca and her much-loved Tenerife. It must have been strange for a woman like her to later become anchored in one city and one house. She must have felt that only her presence, her authority — that authority which her departed ones and her books gave her — prevented her from being under siege.

How did she survive for so many years? What did she eat? Who visited her, or who cut her hair? Which allies remained with her? Did they watch over her, or denounce her? Steal from her to frighten her? What nightmares could frighten a woman like that? How did she tolerate the harshness of being old in Cuba? She did, however, always manage to keep herself above any vulgarity and above people’s questioning.

Dulce María’s dignity, however, reaches a point at which it was difficult to maintain: at the Cervantes Prize acceptance ceremony in 1992 she loses the ability to speak. Her speech is read for her by Lisandro Otero — as lifelessly as a ventriloquist’s dummy. Otero, a commissioner with pretentions of being a writer, “a pastiche of Carpentier and Durrell” — as Pedilla described him — and one who would never have arrived at the assembly hall of the University of Alcalá under his own merit, must have trembled with jealousy when, years later, Guillermo Cabrera Infante was awarded the same prize.

Miraculously, Dulce María’s words are not distorted by the other person’s voice. She speaks about Cervantes and his “immortal book”, and allows herself, before the Spanish royals, an anecdote about the War of Independence: In 1895, her father, Enrique Loynaz del Castillo, took part in an expedition to Ciénaga de Zapata. Breaking into the jungle, he comes across someone asleep: it’s a Spanish soldier who’s somehow been left behind, and who’s head is resting on a copy of Don Quixote.

In a lovely episode from Soldados de Salamina [Soldiers from Salamina], the man manages to escape, but he leaves behind the book and a leather case, “rich with jewels”. Loynaz eventually returns the booty but keeps the book, which he’s started to read underneath a tree, in order to avoid the bother of having to cross the swamp. After a while the other soldiers hear his guffaws. “Carry on laughing”, his companions tell him, and they beg him to read the book out loud to them — because he’d discovered “a way of escaping from hell”.

“It isn’t hard to cry on your own. However, it’s almost impossible to laugh on your own”, the elderly woman finishes by saying, through the man’s voice. The nervous faces in the hall wait, sure in the knowledge that there’ll be some words of criticism for Castro’s regime, a final, rousing fighting speech. However, instead Dulce María talks about writing as a salvation for the “pursued and the misplaced”, like Cervantes, like captain Loynaz, like herself. Did she need to add anything else?

Dulce María returns for a final time to Havana. She tells someone that she’s come to think about Havana in the same way that she thinks about animals — dogs and birds. Her father never agreed to keeping the latter in cages, because in her house, she says, there was always a great passion for freedom. And what a house it was to live in. Carpentier tells us that the the Loynaz siblings had turned the working day on its head. They woke up at five in the afternoon and, as if emerging from coffins, they lived by night. It’s well known that all of them were poets and all had a great sense of memory.

The house was Dulce María’s other ‘avatar’. In her lament for the mansion’s “final days” — written, as a prophecy, in 1958 — she misses “that effervescent life”. In one of her last interviews, her voice trembles: “It made me suffer a lot in my life seeing the sorry state that the house got into over the last few years. But I couldn’t do anything to save it. So the only thing I hope and wish for is that it ends up by just collapsing”.

A woman’s best quality is her mystery. Dulce María always respected that. One can re-read her with much pleasure, but nothing impresses one more than her ethics. Around her — today as much as yesterday — swarm the political writers, the satirists, militants, spies, sectarians, the effete, the dissidents, the exiled, the indifferent, the mediocre, the brilliant, the vulgar and the opportunists. Any old snitch or informer can provoke her with a question but she doesn’t bat an eyelid. “The Havana of today? Better not to talk about it. Excuse me”. And she gets up to go and look at her collection of fans.

Translated by Ricardo Recluso

____________

COLLABORATE WITH OUR WORK: The 14ymedio team is committed to practicing serious journalism that reflects Cuba’s reality in all its depth. Thank you for joining us on this long journey. We invite you to continue supporting us by becoming a member of 14ymedio now. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.