— ADDITION to ORIGINAL POST —

— SECOND ADDITION —

English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

— ADDITION to ORIGINAL POST —

— SECOND ADDITION —

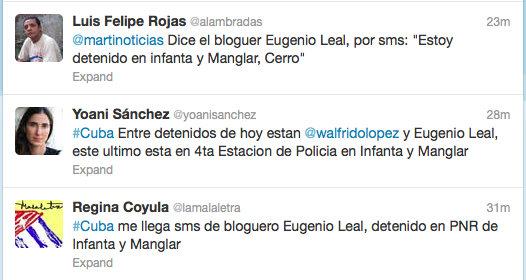

According to tweets not posted here, the apparent plan to stage a “repudiation rally” at Estado de Sats was called off after Antonio Rodiles, manager of the project, delivered a complaint to the police (see third post down). So “Movie Night” went off as scheduled although people were blocked from reaching the site, and some were arrested as they left.

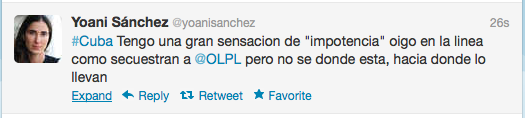

Yoani: Among detainees of today are Walfrido Lopez and Eugenio Leal, the latter is at 4th Police Station at Infanta and Manglar

Regina: Received text message from blogger Eugenio Leal, detained by PNR [National Revolutionary Police] at Infanta and Manglar.

In 1994 I spent many hours sitting on the wall of the Malecon. I preferred the area between the Gervasio and Escobar streets, which I called “my dirty piece of sea.” That was a border between the abyss and the abyss. On one side the rocks and the waves, on the other a sequence of ruined houses and starving figures looking out over their balconies. Still, this place allows me to escape the day-to-day strangulation of the Special Period. If my stomach burned from emptiness, there was still the hope of finding someone hawking — in a whisper — pizzas or paper cones of peanuts. When the power cuts made it impossible to be in my hot room, I also went looking for the sea breeze as a relief. On that concrete I loved, cried, stared at the horizon wanting to run away, and even passed a few nights.

But on the morning of August 5 of that year, the Malecón became a battlefield. Around the ferry dock to Regla people were gathering, encouraged by the hijackings of several boats throughout the summer. An extended sensation of the end, of chaos, of “zero hour” was palpable in the atmosphere. Those waiting to take “the next boat to Florida” were the poorest, those with the least to lose, those ready for anything. Their disappointment was great when they learned there would be no chance of getting on any of these boats. Undoubtedly, that was the spark of the popular revolt that broke out immediately afterwards; but the fuel of the protest was hunger, scarcities and desperation.

A contingent of construction workers, disguised as “enraged people,” lashed out against the unarmed crowd with stick and iron bars. The order from on high was clear: crush the rebellion, but don’t leave behind any imaged of anti-riot troops repressing the people. The epithets launched against the outraged of that day were “lumpen, vermin, criminals and counterrevolutionaries.” The majority of them would emigrate in the coming weeks, on homemade rafts, or simple truck cabs mounted on inner tubes. Others were sent to prison for facing the shock troops. Fidel Castro showed up in the middle of it all — only once the situation was under control — and the official media displayed his presence there as the confirmation of a great victory. But the truth is that after a few weeks the government had to permit farmers markets to relieve the misery. Without the pressure exercised that August 5, we would have ended up like a “Democratic Kampuchea” in the middle of the Caribbean, like the experiment of a stubborn tropical Pol Pot.

I no longer like sitting in front of my dirty piece of the sea. Some of the horror of that August 5 is still there, sandwiched between the cracks in the wall.

6 August 2012

In less than a year the Cuban opposition has lost two of its most important leaders. On October 14 of last year life of Laura Pollán, the principal coordinator of the Ladies in White and the key figure in the release of the Black Spring prisoners, was cut short. A week ago a car crash, yet to be fully explained, claimed the life of Oswaldo Payá, founder of the Christian Liberation Movement.

These activists had great national and international recognition and their physical absence comes at a time when the dissidence is seeking new horizons. Hence, the need to analyze the scenario in which these deaths have occurred, and their potential impact on the immediate future.

On thing about which there is no doubt, is that the Cuban opposition on the Island is characterized by its peaceful nature and its renunciation of armed violence. It prefers to base its actions in political programs, documents demanding respect for Human Rights, street demonstrations, signs painted on facades, or simply open door meetings.

It behaves and manifests a much more democratic behavior than the government installed in the Plaza of the Revolution. Within the ranks of the dissidence there is a great variety of opinions with respect to possible paths and outcomes of the transition. Although some of these routes diverge, there are numerous points on which all converge. The urgent need for political, social and economic changes is the common thread that runs through civil society.

Calls to end the harassment of dissidents, arbitrary arrests and politically motivated prison sentences, form a part of this common agenda. In addition, everyone agrees that Raúl Castro’s government has exhausted its solutions to pressing national problems.

To talk or to overthrow

Although many schemes have been offered to classify the Cuban opposition, most of the studies have focused on the political leanings of the groups within it. Some analysts have established generational breaks, between the historical opposition and much younger actors. In practice, however, it is not political colors or age that differentiate most markedly the dissimilarities between dissident organizations. A key point is the legitimacy they assign to Raúl Castro’s government in their agendas and their proposals for change.

Some maintain that dialog with the authorities could possibly lead to a non-violent transition. Within this line of thinking are distinguished figures such as José Daniel Ferrer, president of the Patriotic Union of Cuba, who believes that “dialog is possible, but from a position of strength within civil society.”

Others dismiss any attempt to deal with the regime, basing their posture on the fact that it was not chosen by a vote of the people in free and direct elections. They see the Communist Party as a kidnapper of hostages with whom there should be no negotiations under any circumstances. To negotiate or to overthrow seem to be the two poles around which current opposition forces are defined.

The United States embargo also constitutes a parting of the ways that defines postures and platforms. Within the Island, many dissidents argue that economic restrictions must be maintained to strangle the government. They believe that allowing fluid trade with the United States or allowing Americans to travel to Cuba would be a source of fresh air that would strengthen the General-President. José Luis García (known as Antúnez), an opposition leader from the center of the Island is one of the main champions of this position.

The great challenge of the people

The Cuban dissidence is denied any opportunity to access the mass media. This significantly limits its ability to broadcast its proposals and political programs. Instead of allowing them even one minute in front of the microphone, Raúl Castro’s government uses television and the official press to accuse them of being “mercenaries in the pay of the Empire,” or “tiny groups of no importance.”

Human rights activist Elizardo Sánchez, opposition leader Martha Beatriz Roque, Catholic layperson Dagoberto Valdés, and the Ladies in White group have all been frequent targets of these media stonings. From different perspectives, these social actors could be key in the years to come, along with several socio-cultural projects such as Estado de Sats, directed by Antonio Rodiles, which even attracts people involved in State institutions. To support these activities with a constant dissemination of information becomes vital, hence the importance of independent journalists and alternative bloggers.

In the current scenario, Oswaldo Payá’s death raises the question of the future of the Christian Liberation Movement, which has many members throughout the Island. That this political force manages to survive the death of its founder will demonstrate the maturity of the entire Cuban opposition.

On the other hand, Raúl Castro has co-opted some of the points that made up the agenda of his political opponents. The aperture for small private businesses, the ability to buy and sell houses and cars, and the leasing of vacant land in usufruct, are all part of the measures implemented by the government in the last four years. Such a scenario obliges the opposition groups to chart new horizons and to redefine their proposals.

30 July 2012

About five hundred people accompanied the body of Oswaldo Payá to his final resting place in the Colon Cemetery. Family members, activists, Ladies in White, foreign correspondents and diplomats based on the island gathered at eleven in the morning. Dozens of dissidents traveled from the central and eastern provinces to the capital in Havana to say their last goodbyes to the leader of the Christian Liberation Movement.

Many of them remained throughout the night and into the morning hours, outside the Parish of Our Saviour of the World where they kept watch on Payá’s body. Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Jaime Ortega y Alamino at eight o’clock, before the coffen left for the cemetery. Those present broke into an emotional applause as the coffin left the Catholic Church, carried through the crowd outside composed of Payá’s followers, the church’s neighbors, plainclothes police and uniformed traffic control officers.

As the funeral procession left the church, several activists were arrested, including Guillermo Fariñas who, like Payá, was awarded the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought.

The funeral procession moved – at high speed – along the central avenues to the city’s main cemetery, with the car windshields displaying a photo of the recently deceased government opponent. Among those present, many wore T-shirts with his face, and formed the letter L – for Liberty – with thumb and index finger. This gesture is the symbol of the Christian Liberation Movement, representing its demands for freedom.

The entire day was marked by the same emotion which, on Monday, had suffused the neighborhood parish that was home to the creator of the Varela Project. His daughter, Rosa María Payá spoke to the congregation in the church to assure them that the family will appeal to justice.

“We do not seek revenge, but we thirst for the truth,” said the visibly saddened young woman, accompanied by her two brothers. Ofelia Acevedo, Oswaldo Payá’s widow, also read a brief statement from the Christian Liberation Movement about the continuity and preservation of the work of her late husband.

The parish pews were crowded and the aisles packed, to the point that it was nearly impossible to move. Among those present were many nuns and members of the Catholic hierarchy. In the words of one of them, “Payá is being honored like a head of state, at least in the popular affection being shown to him during his farewell.”

Today, in a humble family vault, lie the remains of a man who was the most promising leader of the Cuban dissidence. Without a doubt, this is a hard blow to the country’s democratic forces, and opens many questions about the future of the opposition movement. Nevertheless, Oswaldo Payá’s funeral has been a show of unity for the country’s growing civic movements.

Crying, shaking, praying in front of his coffin, were the faces of all his fellow travelers, even those whose programs diverge significantly from those of the Christian Liberation Movement. The pain brought together in one place, and around a single figure, those who, more than once, had distanced themselves due to political and programmatic differences.

The great challenge will be to maintain the convergence achieved in these two days of formal mourning.

Throughout Oswaldo Payá’s wake and funeral an intriguing question has been making the rounds of those present. One that scrutinizes that accidental character of the incident where he lost his life, along with the young Harold Cepero, and that also resulted in injuries to two foreigners, citizens of Spain and Sweden.

While many insist on pointing to the repressive forces as the cause of the crash, others prefer to wait for the testimony of the two tourists to come to light. Meanwhile, the surveillance and threats continue, raising more doubts about what happened. However, the police investigation has just begun, and the two survivors will be key pieces in clarifying what transpired.

For now, in a small tomb in Christopher Columbus Cemetery in Havana, rests the body of a person whose peaceful struggle marked the most recent history of Cuba.

24 July 2012

No one should die before reaching their dreams of freedom. With the death of Oswaldo Payá (1952 – 2012), Cuba has suffered a dramatic loss for its present and an irreplaceable loss for its future. It was not just an exemplary man, a loving father and a fervent Catholic who stop breathing yesterday, Sunday, but also an irreplaceable citizen for our nation. His tenacity shone forth since I was a teenager, when he chose not to hide the scapulars — as so many others did — and instead publicly acknowledged his faith. In 1988 his civic responsibility was forged in the founding of the Christian Liberation Movement, and years later in the initiative known as the Varela Project.

I remember — as if it were yesterday — the image of Payá outside the National Assembly of People’s Power on that March 10, 2002. The boxes filled with over 10,000 signatures in his arms, while he delivered them to the infamous Cuban parliament. The official answer would be a legal reform, a pathetic “constitutional mummification” that would tie us “irrevocably” to the current system. But the dissident of a thousand and one battles was not dissuaded and two years later he and another group of activists presented 14,000 more signatures. With them they demanded that a referendum be called to allow freedom of association, expression, and the press, economic guarantees, and an amnesty that would free the political prisoners. With the disproportion that characterized it, Fidel Castro’s government answered with the imprisonments of the Black Spring of 2003. Over 40 members of the Christian Liberation Movement were sentenced in that fateful March.

Although he was not arrested at that time, for years Payá suffered the constant surveillance of his home, arbitrary arrests, repudiation rallies and threats. He ever missed a chance to denounce the prison conditions of some dissident, or another wrongful conviction. I never saw him break down, or yell, or insult his political opponents. The great lesson he left us is his equanimity, pacifism, putting ethics above differences, the conviction that through civic action and through legal action, an inclusive Cuba is closer to us. Rest in peace, or better still, rest released.

23 July 2012

At five in the afternoon on July 22, the death of opposition leader and founder of the Christian Liberation Movement (MCL) Oswaldo Payá was confirmed. The news started as a rumor that spread during the early hours of Sunday afternoon.

Known nationally and internationally for organizing and carrying out the Varela Project, his death at the age of 60 is a hard blow to the pro-democracy forces in Cuba. Social networks quickly did their utmost to spread the news and the hashtag #OswaldoPaya trended globally. The renowned dissident lost his life in a car accident — the facts of which are still unclear — which occurred around 1:50 pm local time.

The incident took place a few miles from the city of Bayamo in the eastern province of Granma, which is about 500 miles from Havana. Near the small town of La Gabina the car left the road and rolled until it hit a tree. It remains to be confirmed if, before the impact, it was hit by another vehicle, as claimed by several sources, or if the driver lost control, as claimed in the official version.

Payá was in the car with the dissident activist Harold Cepero who also died some hours after the accident. The two Cubans were traveling accompanied by two foreigners, the Spaniard Angel Carromero, 27, and the Swedish politician Jens Aron Modig, 27. Carromero is a lawyer and advisor to the City of Madrid, and secretary of the New Generations of the People’s Party in the Spanish capital. Modig chairs the Christian Democrat Youth League.

All were taken to the Professor Carlos Manuel Clinical Surgery Hospital in Bayamo, where hospital officials said that Oswaldo Payá was already dead when he arrived. After hours of incomplete reports, his wife Ofelia Acevedo was notified of his death through a Catholic Church source.

The two injured have been hospitalized in the same facility and, according to confirmations from El Pais newspaper, only suffered minor injuries. The entire hospital is surrounded by a heavy police operation, and it is impossible to communicate by telephone with the room where both Angel Carromero and Jens Aron Modig are being treated.

Rosa María Payá, the daughter of the deceased dissident, told several media that “they wanted to hurt” her father, “and ended up killing him.” Similar suspicions are growing among opposition figures as well, but will have to wait for the testimony of the two survivors and for the results of police investigations.

The Varela Project

In 2002 Oswaldo Payá received the European Parliament’s Sakharov prize, which was specially awarded for his work on the Varela Project. This initiative proposed a constitutional amendment under a process supported by legislation then in force on the Island. Through the Varela Project, he proposed the holding of a national referendum to allow free association, freedom of expression and of the press, called for free elections, promoted freedom to engage in business, and called for an amnesty for political prisoners.

Together with other members of the Christian Liberation Movement and activists of the banned opposition, Payá managed to present the National Assembly of People’s Power some 11,000 signatures on March 10, 2002. Two years later another 14,000 signatures were added, but the Cuban government rejected the demand for a popular referendum.

Instead, the official response was to declare the socialist character of the country’s prevailing system irrevocable, in a gesture that was popularly called the “constitutional mummification.” Surveillance and repression around Payá increased from that date, including arrests, threats and repudiation rallies in front of his house.

In March 2003, when the Black Spring occurred, about 40 members of the MLC were among the 75 defendants. Their sentences ranged from 6 to 28 years in prison on charges of violating national sovereignty. The vast majority of them had to wait to be released until 2010, when an unprecedented dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Cuban government ended with the freeing of these dissidents. Although Payá was not arrested or prosecuted, during all this time he did not cease to denounce the situation of the convicted activists.

Secularism and civility

Born in 1952 and raised in a family with a strong Catholic tradition, Oswaldo Payá had a religious upbringing. He attended a Marist Brothers school until 1961, at which time it was taken over by Fidel Castro’s government. When he was just 16 he did his military service and during that stage of his life was punished for refusing to transport a group of political prisoners. That refusal caused him to be sent to serve three years hard labor on the Isle of Pines.

On finishing this sentence he joined a parish youth group in his neighborhood of Cerro. Indeed his outstanding labor as a layperson led him to work on the process of Cuban Ecclesiastic Reflection (REC) and he served as delegate to the Cuban National Ecclesiastic Meeting (ENEC) in 1986. In parallel to his opposition activities he continued to work as a specialist in electrical equipment for a State agency. He had graduated as a telecommunications engineer.

In 1988 Payá founded the Christian Liberation Movement that quickly became one of the most important organizations of the nascent Cuban civil society. He also participated in drafting the Transitional Program to promote political change in the largest of the Antilles. From his status as a prominent leader he signed the Todos Unidos [Altogether] manifesto and served as coordinator for its rapporteur commission.

In 2009 he developed a Call for the National Dialogue and at the time of his death was championing an initiative to allow Cubans to freely enter and leave their own country. But his breakthrough as an opponent had come with the creation and dissemination of the Varela Project, an initiative that began to be developed by the MCL in 1998.

For his work he was awarded the W. Averell Harriman Prize, awarded annually by the National Democratic Institute in Washington and the Homo Homini Award of the Czech foundation People in Need. New York’s Columbia University named him an honorary Doctor of Laws and he was nominated several times for the Nobel Peace Prize. He was received in Rome by Pope John Paul II during the same trip that took him to the European parliament ceremony for the Sakharov Prize.

On his death he left three children, Oswaldo José, Rosa María, and Reinaldo Isaías, and also his widow Ofelia Acevedo.

With the death of Oswaldo Payá the Cuban opposition loses one of its most outstanding figures in both the national and international arenas. Gone, physically, is a politician of great importance for the political transition in the island, a prominent layman in the Catholic Church, and a man who was a bridge between the Cuban diaspora and the nation.

The body of Oswaldo Payá will be transferred to Havana where there will be a wake in the parish of Cerro, the neighborhood where he lived.

23 July 2012

Havana, Cuba (CNN) — In the ’90s a certain joke became very popular in the streets and homes of Cuba. It began with Pepito — the mischievous boy of our national humor — and told how his teacher, brandishing a photo of the U.S. president, launches into a harsh diatribe against him.

“The man you see here is the cause of all our problems, he has plunged this island into shortages and destroyed our productivity, he is responsible for the lack of food and the collapse of public transport,” the teacher says.

After these fierce accusations the teacher points to the face in the photo and asks her most wayward student, “Do you know who this is?” Smiling, Pepito replies, “Oh yes, … I know him, it’s just that without his beard I didn’t recognize him.”

The joke reflects, to a large measure, the polarization of national opinion with regard to our economic difficulties and the restrictions on citizens’ rights that characterize the current Cuban system. While the official discourse points to the United States as the source of our greatest problems, many others see the Plaza of the Revolution itself as the root of all the failures of the last 53 years.

True or not, the reality is that each one of the 11 administrations that have passed through the White House since 1959 has influenced the course of this island, sometimes directly, other times as a pillar of support for the ideological propaganda of Fidel Castro’s government (and now that of his younger brother Raúl).

Hence the growing expectations that circulate through the largest of the Antilles every time elections come around to decide who will sit in the Oval Office. Cuban politics depends so greatly on what happens in the ballot boxes on the other side of the Florida Straits — and some share the view that we have never been so dependent on our neighbor to the north.

Cuban diplomacy seems more comfortable contradicting America than seeking to solve the problems between the nations, which is why many analysts agree it would be easier for Raúl Castro to cope with an aggressive policy from Uncle Sam than with the more pragmatic approach of Barack Obama.

Obama’s easing of the rules on family remittances, reestablishing academic travel, and increasing cultural exchanges add up to an unwieldy formula difficult for the Castro regime’s rhetoric to manage. But the regime has also tried to wring economic and political advantages from these gestures from Washington.

The real question in this dispute is which approach would more greatly affect democratization in Cuba — to display a fist? Or to offer a hand? To recognize the legitimacy of the government on the island? Or to continue to treat it as a kidnapper holding power over 11 million hostages?

When the Democratic party, led by Barack Obama, came to the White House in January 2009, our official press was faced with a dilemma. On the one hand the newly elected president’s youth and his African descent made him immediately popular with Cubans, and it was not uncommon to find people walking the streets wearing a shirt or hat displaying the face of the former senator from Illinois. It was the first time in decades that some compatriots dared to publicly wear a picture of the “enemy” (the U.S. president) himself.

For a population that saw the top leaders of our own government approaching or passing 80, the image of a cheerful, limber, smiling Obama was more consistent with the myth of the Revolutionary than were the old men in olive green standing behind the national microphones.

Obama’s magnetism also captivated many here as well, and disappointed, of course, those who hoped for a heavier hand toward the gerontocracy in Havana.

Farewell socialism … hello to pragmatism

Beyond the political issues, the measures undertaken by the Obama administration were felt quickly in many Cuban families, particularly in their economy and relations with their exiled relatives in America.

With the increased cash from remittances, the small businesses that emerged from Raul Castro’s reforms were able to use the money coming from the north for start-up capital and to position themselves. Meanwhile, thousands of Cuban-Americans arrived at José Martí airport every week loaded with packages, medicine and clothes to support their relatives on the island.

Those who see the Cuban situation as a pressure cooker that needs just a little more heat to explode feel defrauded by these “concessions” to Havana from the Democratic government. They are the same people who suggest that a hard line — belligerence on the diplomatic scene and economic suffocation — would deliver better results.

Sadly, however, the guinea pigs required to test the efficacy of such an experiment would be Cubans on the island, physically and socially wasting away until some point at which our civic consciousness would supposedly “wake up.” As if there are not enough historical examples to show that totalitarian regimes become stronger as their economic crises deepen and international opinion turns against them.

No wonder Mitt Romney is a much talked about figure in the official Cuban press. His strong confrontational positions feed the anti-imperialism discourse like fuel to a fire. The Republican candidate has been the focus of numerous articles in the official organ of the Communist Party, the newspaper Granma. His photos and caricatures appear in this same daily that was stymied when trying to physically mock Obama. Given the high rate of mixed marriages among Cubans, it’s quite sensitive to enlarge the ears and fatten the lips of the U.S. president without it reading as racist ridicule.

If, in the eighties, the media’s political humor was honed in the wrinkled face of Ronald Reagan, and later the media had a field day with the physique of George W. Bush, for four years it has been cautious with the current resident of the White House. All this graphic moderation will go by the wayside if Mitt Romney is elected as the next president of the United States. There are those who are already laughing over the possible jokes to come.

But whoever scores the electoral victory will find Cuba in a state of change. The reforms carried out by Raúl Castro lack the speed and depth most people desire, but are heading in the irreversible direction of economic opening. Havana is full of private cafés and restaurants, we can now buy and sell homes, and Cubans are even managing to sell the cars given to them during the era of Soviet subsidies in exchange for political loyalty. The timid changes driven by the General President are threatening to damage the fundamental pillars of Fidel Castro’s command. Volunteerism at any cost, coarse egalitarianism, active adventures abroad, and a country kept in a state of constant tension by the latest economic or political campaign appear to be gradually fading into things of the past.

On the other hand, citizens themselves have begun to experience the most definitive of transformations, that which occurs within. Public criticism is on the rise, although it has not yet found ways to be heard in all its diversity, but every day the fear of police reprisals diminishes.

The official media have unquestionably lost a monopoly on the flow of information and thanks to illegal satellite dishes Florida television now comes to Cuba. Alternative news networks circulate documentaries, films, and articles from independent journalists and bloggers. It’s as if the enormous ocean liner of Revolutionary censorship was taking on water through every porthole.

Young people are finally pushing to have Internet access, while the retired complain about their miserable pensions and almost everyone disagrees with the travel restrictions that prevent our leaving and returning to our own country. In short, the illusion of unanimity has fallen to pieces in Raúl Castro’s hands.

To this internal scenario, the result of the American elections could be a catalyst or obstacle for changes, but it is no longer the most important factor to consider. Although the billboards lining the streets continue to paint the United States as Goliath wanting to crush little David who represents our island, for an increasing number of people the metaphor doesn’t play out that way. They know that in our case the abusive giant is a government that tries to control the smallest aspects of our national life, while his opponent is a people who, bit by bit, is becoming more conscious of its real stature.

CNN Editor’s note: This is the fifth in a series of dispatches exploring how the U.S. election is seen in cities around the world. Yoani Sánchez is the Havana-based author of the blog Generation Y, which is translated by volunteers into 20 languages, and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. This article was translated by Mary Jo Porter.

10 July 2012

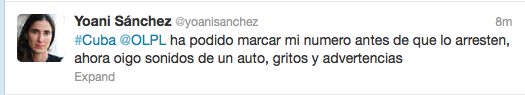

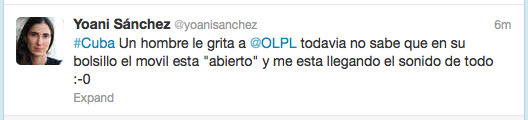

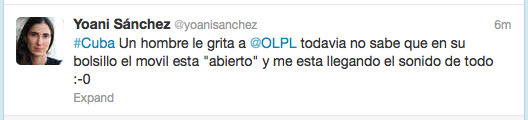

Translated by Mara from Yoani’s Twitter

Translated by Mara from Yoani’s Twitter

Thanks to Mara’s daily efforts, you can follow Yoani’s Twitter in English here.

1 July 2012

In case you missed it:

Yoani’s recent blog post about Fidel’s “Moringa Reflection.”

Fernando Dámaso’s recent blog post also about Fidel’s Reflections.

Only since March of 2008 have Cuban citizens living on the island been able to contract for cellphone service. Before that it was the exclusive privilege of trusted officials and foreigners living on or passing through the island. With the ingenuity that characterizes us, we managed to skirt such difficult obstacles.

It was not uncommon to see Cubans station themselves at the country’s tourist centers “on the hunt” for a tourist who would do them the favor of contracting for cellphone service. The fact that the service was offered only in the form of prepaid cards made the trick that much easier. The foreigner “showed his face” to the Cubacel official who demanded a passport from another country, and then left his Cuban “friend” with the greatly desired SIM card.

Fortunately, one of Raul Castro’s first reforms was to eliminate what was known as “tourist apartheid,” although he substituted something worst… not written in the fine print of the contract. That is the prohibitive prices that make cellphones in Cuba a service available only to the wealthy—or politically reliable—sectors of the population.

To translate the expression “prohibitive prices” into figures comprehensible to any earthling, let’s look at some examples. To do that, it is first necessary to understand that Cuba has two currencies. The Cuban Convertible Peso (CUC)—which is not actually convertible into any other world currency—is pegged to the U.S. dollar, but after the exchange fees is only worth about 90 cents. Many products in Cuba are available only in CUCs. The second currency is the Cuban peso (CUP), also called “national money” and this is the currency in which we are paid our wages; twenty-four Cuban pesos equal one CUC. The average monthly salary on the island is 350.00 Cuban pesos, or 14.50 CUC, about $13 U.S. The highest monthly salaries are the equivalent of about $20.

To send a text message from Cuba to a phone abroad costs one CUC. So a simple message of greeting to a family member in Madrid or Buenos Aires would cost the average Cuban almost seven percent of his or her salary. Translated to the average national wage in the United States (about $3,500 a month), this would be the equivalent of $240 to send one text message, meaning the average American worker could spend his or her entire salary to send 14 or 15 text messages a month.

As absurd and exploitative as this seems, it is possible in today’s Cuba because we live with a monopoly of a single, State-owned telephone company called ETECSA. Our “socialism with opportunities for all,” is actually a system that defrauds its clients who have no rights to demand redress. Many Cubans joke that the initials ETECSA stand for “We are Trying to Communicate Without Trouble,” rather than their real meaning: Public Telephone Company of Cuba.

Who on the Island can afford these prices? The answer is complex, but worth taking the time to explore: those who work in corporations where they receive a part of their salary in CUCs; those who receive remittances from a relative in exile; those who have shady black market businesses; those who demonstrate such ideological affinity with the government that they ascend to jobs “with subsidized cellphone included”; those who travel abroad as musicians, as superior athletes or as Cuban technicians on official missions; those who work for themselves in some profession that produces more income than state employment; and also those who can count on the support of a friend living elsewhere on the globe.

If none of these paths existed—some illegal and others ethically reprehensible—Cuba would be a mute island with regards to cellphones, a black hole of communication. Fortunately, we are not.

The high costs of cellphone service are intended to raise the greatest possible amount of that desirable currency that the Cuban government needs to survive. So every text message a Cuban sends overseas helps to finance not only the infrastructure—inefficient and unstable—of phone antennas, ETECSA offices and the tie-wearing functionaries and their secretaries, but also part of the official propaganda on TV, weapons that are bought for a war that never comes, and even snacks for the political police who keep an eye on the non-conformists.

In short, without realizing it, we are subsidizing our own chains, we send a text message and with it we feed the censor who reads it on the other end of the line and the bureaucrat who is ready to cut off our service if he thinks the words sent “threaten national security.”

What would you do in such a case? Would you let it go? Renounce it? Protest? Would you vegetate in the morass of non-communication, aware of living under a State that owns all the businesses and all possible words? Would you demonstrate your outrage in some public place? There is not shortage of us who would like to do the same!

But it turns out that you—in the case “we”—are trapped in material deprivation, in a system that condemns us to a cycle of survival and guilt any time we manage to fly a little higher. Many even claim that the high cellphone prices in Cuba aren’t just to bring money into the State coffers, but also to prevent the wider use of this tool.

With just 1.8 million cellphone users on an Island of 11 million people, it’s clear that we are bringing up the rear of the communication train in Latin America. What’s more, landline phones are also less common here, and many Cubans have never had a home phone—that heavy contraption with a rotating dial, instead of a gadget with a screen and keys. Can you imagine that scary technology? If so, you can understand the awe of Cubans who have a Nokia or Motorola or some other model that rings in their pockets.

Those who finally manage to carry that ringing with them everywhere feel themselves members of a “brotherhood” of cellphone customers, chosen by economic chance often unrelated to how hard-working or socially important a person is. So the next step after contracting for service in one of the offices with the long lines and half-asleep employees, is to take care—however you can—that the ETECSA monopoly doesn’t cut your service.

How can you manage that? Shut up, fake it, don’t talk about any difficult issues on the phone, definitely don’t talk about that “dirty” thing called politics. Every Cubacel user senses that their phone could be like the waiting room at the train station, where every ear is listening. And these are not the paranoid delusions of Cubans, it’s common sense in a country where official television plays the recordings of people’s phone calls—recorded without any authorization from a judge or a court—where one dissident is talking with another, a citizen sharing critical opinions, through the ether of cellular service.

Paternalism, the constant observance and presence of the State, gives citizens the impression that any step over the line is illegal. The cellphone—most of our compatriots believe—is a gift to us, not a service that we ourselves pay for. While using it we must observe the same ideological guidelines that we follow at our school desks, at our jobs in some official institution, on the bus owned by the only legally permitted bus company. This gadget that connects us to another, for the ordinary Cuban, is linked to the fear that one day the service will be cut off for stating a critical phrase or an opposing view.

And so you ask us why there isn’t a North African style revolution in Cuba? How will we call ourselves together if the barely 11% of the population that owns cell phones treats them like precious jewels, like luscious fruit obtained after much difficulty that could be in danger if used for civic activities. Can you imagine for one minute a Spanish 15M activist paying 69 euros for a single text message? Think about the Occupy Wall Streeters with no ability to send chain messages to others who share their ideas, because the telephone monopoly cut off their service. Think about the Chilean student activists without the ability to communicate their dissatisfaction through social networks. Comparing realities is a risky thing, but it also helps to understand the limitations, we face.

It all became more complicated after 2008 when numerous Twitter accounts began to be opened outside the bounds of the official institutions. First awkwardly, and then in fascination, several citizens began to discover the potential of 140 characters. It seemed something unattainable for us ordinary disconnected Internauts. Keep in mind that throughout the 42,000 square miles of the Island, there is not one office where a citizen can go to contract for home Internet. This is a privilege enjoyed only by foreigners living in the country (how symptomatic!), or by the most trusted local artists and functionaries.

Fortunately, many of do not agree with the ideological kilobyte divide and dare to buy access on the great World Wide Web on the black market, or at least to knock on the doors of some embassy that provides access to the web, knowing that the official propaganda will make us pay a high political price. Others dare to use even more creative ways to reach cyberspace.

But this little blue bird, this social network used by so many all over the world, flitters here in another way. While the great majority of Twitterers do it from a computer (with TweetDeck and other applications), here only a few enjoy this possibility. You can choose to access this service from an institutional connection, which inevitably involves ideological concessions, or to declare yourself a fugitive-Twitterer and do it however you can. On the latter path is the possibility of posting to Twitter from text messages, a service that brings this social network to those dispossessed of access to the web—meaning any individual located anywhere in the world has access to it.

From Lisbon to Sidney, anyone who has a Twitter account and a cellphone can update their status through text messages, although with the limitation of not knowing what others are writing or what themes are trending on the network. But it is an option.

If you choose to Tweet from the physical comfort of official institutions, on the other hand, the content will in many ways be conditioned on the ideological directives of those places. Let me be clear that I am not trying to characterize all those who use a State connection as “official bloggers or Twitterers”… Not at all! Because that would be to fall into the same definitional scheme maintained by government propaganda. Among those people, some escape from this straitjacket—maintaining Twitter accounts completely detached from social or political reality—with texts in the style of, “Hi, friends… how beautiful is the sun this morning… and have you ever seen such a gorgeous sea?”

Others are sitting in front of their official computers, salary included, precisely to crack down—on the Internet—on voices that criticize of the system. You don’t believe me? Why then, as soon as the workday comes to an end, do the “official voices” disappear? Why do so many of those who attack government critics not dare to show their faces and hide behind the protection of a pseudonym? Why is it that sometimes they publish information that could only have come from the political police? Haven’t you wondered why so many show up with the same nickname at the same time every day, as if they were directed, commanded “from above?” On Twitter the soldier leaves traces of his position. In the midst of this spontaneity of the social web, partisan positions are easily detected.

So to express yourself on the web, to be a Twitterer in Cuba, is inextricably intertwined with your pocketbook and your ethics… because we live in a country where not only are differences of opinion penalized, but prosperity is as well. Let’s suppose for a minute that you are a successful entrepreneur—a difficult thing to be in the midst of high taxes and the lack of a wholesale market, but still, let’s consider this utopian example—and we read the hypothetical stream of tweets that you generate. Most likely it’s limited to talking about the recipes you prepare in your restaurant, the lovely rooms you rent, or the incredible car repair service you provide. You will say little, very little or nothing, in the way of social critique. Because you know that by doing so you’d be risking your license for self-employment, for which you’ve already paid so much.

Since childhood, you were taught in school that every opinion running around in your head should stay right there, where no one will hear it or, perhaps, you will whisper it to a friend, or to your partner when your heads touch on the pillow. Why would you jeopardize your small daily survival and throw yourself under the enormous microscope of power? For a few simple tweets launched like a bottle on the sea into cyberspace?

I understand it, but I do not applaud this attitude… I’m sorry, I’ve already found my voice and I cannot go back to silencing it.

Let’s continue taking you as an example—don’t think you can get out of it—and conjecture that, despite your salary of $13 USD, or your meager earnings at your private snack bar, you won’t want to give up expressing yourself on the social networks. A friend undertakes the steps to connect your cellphone to Twitter, your brother lives in Costa Rica and promises to recharge it for you over the Internet so you can use it to publish text messages… and having been silenced for so long, you have a lot to say…

Once you start in on the exorcism in 140 characters, Cubacel follows up with some short disconnects of your service, and new faces start showing up in your neighborhood—lurking behind columns and under the stairs. Your friends no longer call your house because you have become a “cyber-warrior,” one of those they see on national television typing on a laptop while elsewhere on the screen a helicopter gunship hovers.

Take a deep breath. Clutch the cellphone in your hand and ask yourself if the same thing will happen to Twitterers who spend their days typing slogans. Will they also update their status from a cellphone supported by a family member in exile? Or, on the contrary, will they be able to enjoy one of those computers permanently connected to an Internet that never disrupts the kilobytes sent in convertible pesos?

You will then begin to understand—or you’ve already sensed—that the whole system is designed to make you feel guilty for having a cellphone, for maintaining a Twitter account and, especially, to make you decide not to use it to raise your small voice—singular and different—to be heard in the global village.

Meanwhile, your brother in Costa Rica is painted by official propaganda as an employee of the CIA, and the various readers who recharge your phone from time to time are practically Satan himself.

You’re in the middle of the room about to toss your cellphone off the balcony and call ETECSA to tell them to put their service where the sun don’t shine, but you stop yourself.

You’re not going to let yourself get sucked into the mentality of the oppressor, you’re not going to let the hand that offers you bits of damp birdseed make you believe that the cage is preferable to the risk of flying free.

From Voces 15 / June 2012