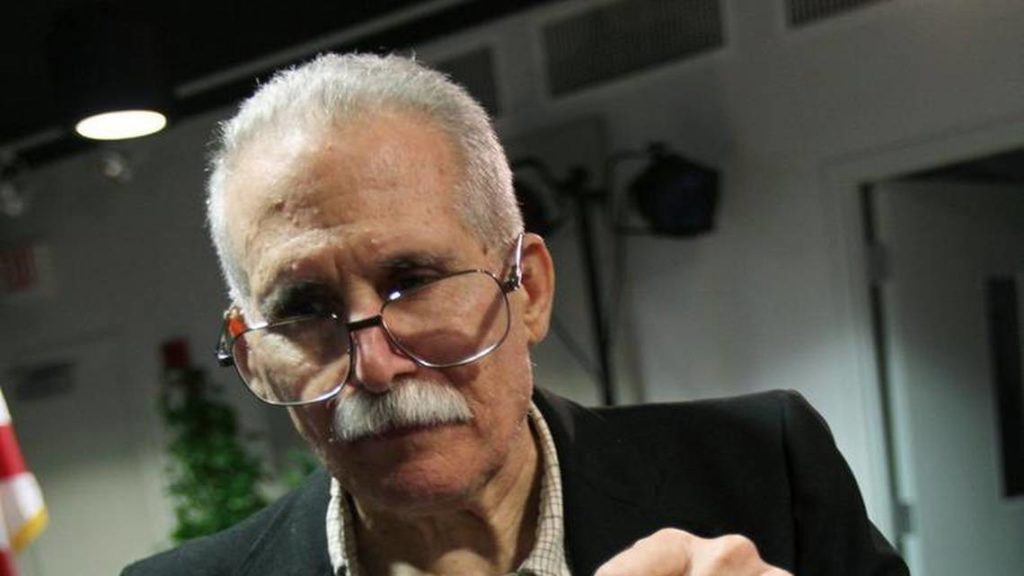

Iván García, 30 April 2018 — Manuel Cuesta Morúa, a 55-year-old Afro-Cuban historian of average height and thin build, is probably one of Cuba’s most intellectually gifted dissidents.

Morúa’s political proposals are based on a social democratic model. He has tried different strategies, looking for a legal angle that would allow him to carry out his projects legitimately. The military dictatorship, however, has thwarted him. He considers himself to be a man of the left, a position from he articulates his ideas.

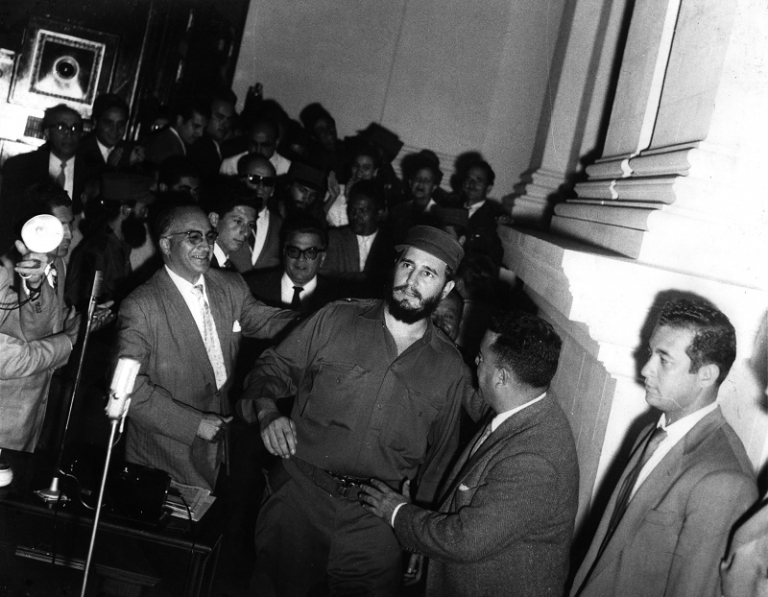

The arrival of Miguel Díaz-Canel — a 58-year-old engineer from the town of Falcón in Villa Clara province, about 300 kilometers east of Havana — marks the first time someone born after the triumph of the Cuban revolution has ascended to power. He is part of a generation that, for differing reasons, began to dissent from the Marxist, anti-democratic and totalitarian socialism established by Fidel Castro. continue reading

The hardline, diehard generation is passing away. In the current political climate, the most eloquent spokespersons, both official and dissident, were born during the height of the Cold War. They experienced the fall of the Berlin wall and the collapse of the international communist bastion, the former Soviet Union.

The dialectical struggle will not be resolved at the point of a gun. The system will have to reinvent itself, unleash productive economic forces and rely on the private sector if it wants to bring an adequate level of prosperity to Cubans frustrated by the precarious conditions of their lives.

At one time Díaz-Canel, Manuel Cuesta Morúa, Luis Cino, Angel Moya and the economist Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello were all in the same ideological trenches. For reasons of their own, they stopped applauding Fidel Castro and began a long, arduous journey aimed at establishing a democratic society in their homeland.

For Morúa, the transfer of power to Díaz-Canel, “can be read in several ways, all of them interesting. The generational change, no matter who is its public face, puts society on a more equal footing when it comes to dealing with those in power,” he says.

He adds, “The only thing left to do now is make demands. Díaz-Canel is an obstructionist president. He has very little legitimacy. He is not a historical figure and he has not won an election. Every person on the street says, ’I didn’t vote for him.’ The government is incorrect when it claims that Cuba holds indirect elections. Elections here are by acclamation. To date, this president has no agenda. He comes off as a clone.”

When I ask him if he thinks it is time for dissidents to change tactics and devise a strategy to reach out to ordinary citizens, Cuesta Morúa responds, “I think it’s time to think more about politics, to offer a clearer alternative. It’s time to step up to the plate, but in political terms.”

In Lawton, a neighborhood of low-slung houses and steep streets on the southern outskirts of Havana, is the headquarters of the human rights group The Ladies in White. Most of its members are mothers, wives or daughters who had never before been interested in politics.

Their dispute with the regime centers on their demands for release of their sons, husbands and fathers, who were unjustly imprisoned by Fidel Castro. Their protest marches, during which they walk carrying gladiolas, were brutally suppressed by agents of the regime’s special services. The Cuban government’s actions led to strong public condemnations from the international community.

After entering into negotiations brokered by the Catholic church and the Spanish government, Raúl Castro’s regime agreed, for the first time, to release some political prisoners and to grant The Ladies in White space along Havana’s Fifth Avenue to carry out peaceful protest marches.

After their release most of the seventy-five former political prisoners left Cuba. The Ladies in White are still subject to brutal repression by the Castro regime, which has denied them access to the space it once gave them permission to use.

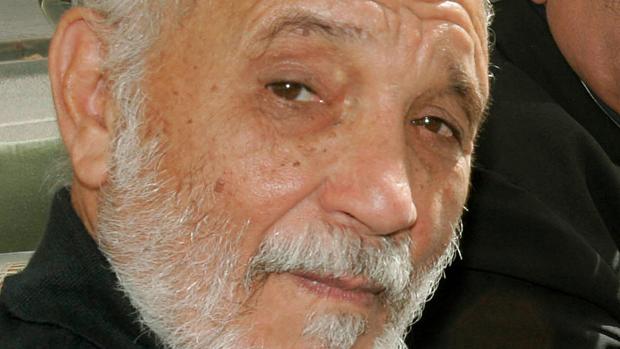

The Ladies in White’s main strategy involves street protests. Angel Moya Acosta, the 53-year-old husband of Berta Soler, leader of The Ladies in White, believes “that the Cuban political opposition needs to confront the regime. If we want people to take to the streets, the dissident community has to take to the streets and to actively persuade the people. This is not a problem about unity. Changing the electoral system in Cuba is up to the opposition and — except for some exceptions such as UNPACU, the Pedro Luis Boitel Front and the Forum for Freedom — that is not happening. Anything else is an excuse for not doing anything.”

According to Moya, the selection of Díaz-Canel was expected. “Nothing in Cuba will change. Repression could even increase. Díaz-Canel indicated that major national decisions will still be made by Raúl Castro. And he ended in inaugural speech with the outdated slogans ’homeland or death’, ’socialism or death’ and ’we will win’.” Everyone on the island knows that real power in Cuba still rests with Raúl Castro.”

Luis Cino Álvarez, 61, one of the strongest voices in independent journalism, says he “does not expect any political reforms from the Díaz-Canel government except, perhaps, some slight fixes to the economy. He has already stated what we can expect: more socialism and a continuation of the policies of Fidel and Raúl Castro. Stagnation in its purest form. I believe that now is the time for dissidents to come up with a better strategy for confronting the regime.”

Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello, a 71-year-old economist, thinks that “Díaz-Canel is a person with many illusions. He held a meeting of the Council of Ministers that was illegal, saying that new appointments to the council had been postponed until July. Díaz-Canel feels very comfortable governing. And that is not a positive thing. When they govern, all the word’s presidents feel pressure due to multiple demands from different sectors of society.” She adds,”Cuban dissidents followed the wrong path. They should have taken the road of the people. But with each step they get further and further away from it.”

If there is anything upon which the fragmented local dissident community agrees, it is that the government of Miguel Díaz-Canel represents the beginning of a significant new era. They face two dilemmas: either find a way to motivate thousands of citizens to demand democracy or watch the military dictatorship celebrate the centenary of Fidel Castro’s revolution with a parade though the Plaza.