The daughter of Oswaldo Paya and Ofelia Acevedo agreed to an interview for Cubanet. Having captivated the public through the media, she insists that neither his undisputed leadership nor she herself that is the most important thing. To discover whether or not there was government responsibility in the events of July 22, 2012, would end with a cycle of violence and impunity for State Security, and the alleged immunity of the authorities to the consequences of the systematic violation of the human rights of all Cubans.

I asked Mrs. Navy this question directly because after the speech to the Human Rights Council — in that two minute speech, I was interrupted by seven countries with “human rights standards,” including Cuba, Russia, Belarus — after that there was a plenum with the High Commissioner, and I was able to directly ask her the question of whether she knew about the case (i.e., the request for an international investigation) and she gave me her condolences, told me they knew about the case and put me in touch with the Rapporteur on Extrajudicial crimes; and that’s when we presented demand, and a few days later they responded by saying that they have the case. It is a process. I’m not saying they are doing an international investigation, I’m just saying what they said: they are working on the case with the United Nations mechanisms, not all of which are public.

I believe that later the United States got up and said something like, “Fine, in any event, we all have the right to speak. We are going to listen to what she has to say.” The United States sat down and the following began to stand up consecutively: China, Russia, Belarus, Pakistan, Nicaragua, I don’t remember which other countries who say they are “standard bearers of Human Rights,” standing up to support “Cuba,” to say, “just to support Cuba’s motion.” But fine, after the last one sat down, the president turned to give me the floor and I could finish.

At this Council they listen to all kinds of things, every day that it lasts — from the slaves of Mauritania, to torture in Iran, and most of the countries don’t react against the Human Rights activists who are talking there. This reaction, apparently planned — because they would have had to talk with China, Pakistan, Russia, Belarus, Nicaragua, because they jumped up at this moment and supported “Cuba” — also indicated their arrogance, their inability to deal with the truth. What we were asking for there was an investigation, we were asking for a plebiscite. We were not accusing anyone, on the contrary, we were proposing a dialogue.

But he was still very rational and very consistent, and also very calm in explaining the facts in a coordinated and accurate way. There were even times when he told me “I don’t remember; what you’re asking me I do not remember exactly. Sometimes I have lapses. They drugged me.” That is, he did not invent anything, and was very accurate. Even when I sometimes theorized, he said, “That I do not know.” And so everything that we said was exactly what we had knowledge of. We have never made up versions of what happened. We have given facts that we have been able to confirm.

He was very willing to support us in everything, and convinced that what he said was the truth and that he would tell the truth where he had to. He spoke to the press when he decided to, and in the way he decided. Some sectors of the Spanish press were at times hostile to him. Maybe that’s why he decided to start by other means. But I think it was also a sum of circumstances: at the time he had decided to speak, the Washington Post asked for an interview. He did it the way he wanted. He told me he was going to do it, and I asked him to do it, too. But perhaps more importantly he was ready, as he put it, to take part in any legal proceedings as a witness, stating the facts of his experience.

How do you interpret the behavior of the Spanish government?

RMP: We tried to see everyone in Spain, to explain to everyone what had happened, because we were asking for support for an investigation, a cause that we know is very just, and that also has much to do with Spain, because two of those involved are Spanish citizens. One of them is my father and the other is Angel Carromero.

To me, the attitude of the government has proven lacking, because of the fact that Angel Carromero is innocent, and the government knows it, because the same text messages that I know about are in the hands of the Spanish government. Yet he is still treated as guilty in a free country where there is knowledge of his innocence. We disagree with this and object to it, and have said so explicitly. I told this to Minister (of Foreign Affairs) García-Margallo who responded that he will not interfere with our efforts to achieve this international investigation.

Have you received indications of support from other politicians and European parliamentarians?

RMP: I met with many politicians in Spain, of various stripes. The PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers Party) did not want to meet with us, and also sent an offensive letter saying that I was using an accident for political purposes. Which was quite deplorable, but in any case the decision not to meet with us was theirs.

But with the exception of the representatives of the PSOE, I have met with leaders of the PP (Peoples Party), the UPyD (Union, Progress, and Democracy), and the CiU (Convergence and Union) parties. Everyone has been supportive and in fact are committed to supporting the international investigation. Many were already committed to supporting human rights in Cuba.

Apart from this attitude of government officials, all the politicians I met with in Spain, from José María Aznar, Esperanza Aguirre, Rosa Diez, Duran i Lleida, or Mr. Vidal-Quadras, a PP member of the European Parliament — as all the European People’s Party deputies, who are 280 of the entire Union — had an attitude of commitment and solidarity with the international investigation, with the holding of the plebiscite, and with human rights in Cuba. And not only Popular Group MEPs. I also talked with independent MEPs, one of whom is Mr. Sosa Wagner of UPyD, who is one of those promoting a declaration requiring an international investigation as a pronouncement of the European Parliament. There are several mechanisms within the European Parliament taking place at this time, with the goal of a statement that demands an international investigation regarding the death of my father and Harold. My father was awarded the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament, so it makes sense that the European Parliament is not silent.

I also met with the Swedish Foreign Minister and the Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs. Their positions have been in solidarity with the international investigation and with human rights within Cuba.

Where can we read the speech to the European People’s Party? Do you want to comment for us on the points raised?

RMP: I made a speech on the floor of the parliamentary group, which was most of the deputies. I read from my notebook, but I transcribed it and sent it for publication on the blog www.rosamaríapaya.org.

At this juncture, when the EU is in negotiations to reach an economic agreement with Cuba, we simply say that the Common Position requires respect for human rights and makes it a condition for the normalization of relations.

We believe that respect for human rights must be measurable and concrete. To simply say “respect for human rights” can be too general. For example, the Cuban government releases the 75, and imprisons another group. But it sells it as a process of change or openness. The same way it selling these reforms. Just as it let me out of the country and says it is because it is changing when it is not real, when in fact Cubans are not able to decide. But it also plays it as a card to show to the European Union and say, “Look, there is respect for human rights in Cuba.”

The proposal in the European Union is: “The signs of respect for human rights in Cuba cannot come from the government; that is, they cannot come only from the government; they must first come from the demands of the Cuban people in exercising their rights.”

Until now, the only demand that is, in fact, a demand from the Cuban people under the law, is the holding of a plebiscite on the Varela Project. If the Cuban government undertakes a plebiscite, if it asks the people, if it meets its own law, its own constitution, and responds to this popular demand, this can be a sign that a process of democratization has begun in Cuba. Until that happens, it cannot be said — because it would not be true — that there is a democratic change in Cuba that would justify such a normalization.

We are not opposed to trade between the EU and Cuba. We are against trade made at the expense of the rights of Cubans. That is, trade must actually be with Cuba, with all the Cuban people, and not just with the government. And that is the proposal: support the demands that effectively come from the people. The “respect for human rights” that you decided to place when you wrote the Common Position can only be measurable if it responds to the demands that are born from the same people. So far these demands are specified in the plebiscite of the Varela Project. The opposition has more strategies, they are the demands of The Way of the People. But as a first step, we would not even say we support the opposition, we say we support the demands that come from people.

Will your public appearances be limited to promoting the international investigation into the case?

RMP: I think it has been quite explicit during these past two months: we as a family and as a movement have the goal of achieving this international investigation. Because we deserve to know the truth, because the people of Cuba deserve to know the truth. It is fair to all Cubans. But also because as a political movement we are looking for a transition that permits national reconciliation, and this requires the recognition of all truth. If not, there can be no reconciliation and no real transition, at least not the kind we’re looking for.

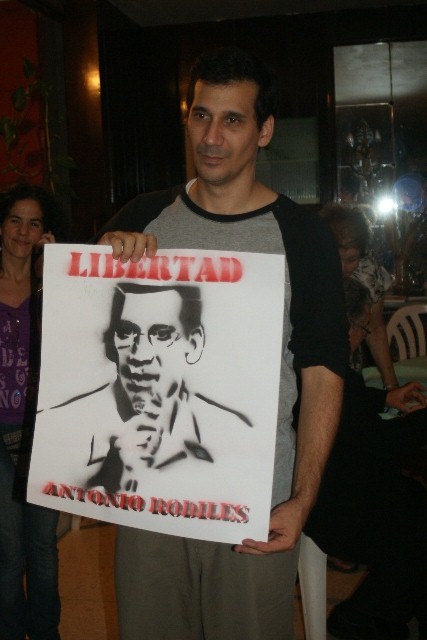

In addition, our efforts for an international investigation was what we were talking about before: we want to know what happened. But we also want to avoid it happening again. And somehow you have to break that feeling of impunity that the State Security of the Cuban government has now. And we believe that an international investigation, with legal consequences for the Cuban government, is a way to break this impunity. And we did not stop there. We asked for precautionary measures. One of them has been for Yosvany Melchor. This is the only one they’re responded to, so far. That is, it has now been ordered.

The Interamerican Commission on Human Rights has recognized a precautionary measure that protects Yosvany Melchor who is a prisoner of the Movement, a prisoner so unique because he is not part of the Movement, the one who is part of the Movement is his mother, Rosa Maria Rodriguez Gil. Three years ago, State Security went to see her and told her that if she did not collaborate with them and if she did not distance herself from the Movement her son was going to pay the consequences. Two days later, her son was jailed and then accused of nothing less than human trafficking, with a contrived trial in which the principal witness said he was not familiar with Yosvany, that he had met him a day earlier in jail when they put them together.

And even so, that witness, who was also one of those implicated in the event, is at home and Yosvany was given 12 years in maximum security prison. He has spent three years. A boy who is now thirty years old and has committed no crime, only because of being the son of Rosa María who is a courageous woman who said to State Security: “I am not going to betray who I am.” And so, the Interamerican Commission has now expressed itself in that regard. There are other precautions underway and also in process is the demand that we will present the week of April 20 seeking an international investigation of the case. They told us that the process was a little long, right now it is being studied. It is still too soon to give a verdict, we know that it is going to be a long process.

Is Rosa Maria Paya going to assume leadership of the Christian Liberation Movement?

RMP: For more than two years I officially have formed part of the Movement, but in any event the whole family is implicated in cases like these. My brothers and I, although we may not be part of the Movement, in some way we collaborate or are influenced by the political work of my father. I am not the leader of the Movement. The Christian Liberation Movement has a Coordinating Council. In these moments, because of the circumstances and also because of my decisions, it is possible that my face may be more visible. But in any case my face is not important. The important thing is the message, and the message of the Movement at this moment, and for the majority of the opposition, has agreed on the demands of the Way of the People.

Recently, the Eastern Democratic Alliance has joined the platform of the Way of the People, which coordinates the Christian Liberation Movement. Could this platform of change successfully unify, and therefore strengthen, the internal opposition?

RMP: None of the legal tools in which we work can be carried out alone. We are talking about the Varela Project, the Heredia Project that right now is in process of gathering signatures. Many organizations in Cuba that are not the Christian Liberation Movement collaborate. In a unique way the demand for a plebiscite: the plebiscite on the Varela Project. We believe that the conditions are favorable, in the first place because it is necessary. We have spent more than 10 years and 25 thousand Cubans are demanding a plebiscite, and the National Assembly is obliged to respond. It is obliged to hold the plebiscite because the legal petition was signed by more than 10 thousand citizens, and this by the Constitution is the same as an answer, that in the case of the Varela Project translates into a question of citizenship, in a referendum, in a plebiscite that they so far refuse to hold.

I believe that we are at a point at which we have common demands, that most of the opposition has signed. A very diverse majority, because there are all colors in the Way of the People. We are also talking about demands that are popularly supported.

Ten years ago the strategy of the Cuban government was to incarcerate the 75 and change the Constitution; in some way it worked to confuse people, frightening and changing a little the priorities of the opposition, which were converted to getting the 75 from the jail and not to achieve a plebiscite. In those moments we believe it is now necessary, now the 75 are out of jail but more than anything the Cuban people now need these changes in a concrete way.

Do you believe the reforms of Raul Castro may drive change towards the freedom and democracy that so many desire?

RMP: The government’s strategy in these recent years has been to sell an image of openness. Using these reforms but also using some publications, using all its marketing apparatus, using its advocacy; selling the picture of change without changing. Making reforms that do not guarantee rights although they touch on important points for Cubans like the entry into and exit from the country.

But in each case the reforms are designed in such a way as to also become a mechanism of control of the Cubans; because they are not a right, they are a concession by the government. And Cubans, whether they read the law or not, have that perception. That is to say, from the one with a café to the person who seeks a passport he knows that he is asking permission, not exercising a right. And he also knows that when he gets the passport or when he sells peanuts, it is a privilege because he can do it. And as he has a privilege he does not want to lose it.

And how are privileges lost in Cuba? By mixing in politics, demanding rights. As is the case of a girl named Madelaine Escobar who is a member of the Movement in Holguin. She has a café. Twice they have withdrawn her license. Each time she has protested, and she protests so much that she ends up in the Police Station, all the questions that they ask her are of the type: How many members are in the Christian Liberation Movement? How many signatures from the Heredia Project? Not one regarding why they took the license. This is illustrative of how each of these reforms is converted also into a measure of control by the Cuban government. And I understand that the international community does not see it the same way because they don’t know these mechanisms.

Supposedly businessmen form part of Civil Society, and an important part, but for the business to be free, first you have to be a free person. In Cuba there are no free people nor are there free businesses. There are concessions, which they give to some people, but besides some people who are more privileged than before, because who has 50 thousand dollars in Cuba in order to start up a “Paladar,” a private restaurant? The cases that we are familiar with are people from the government. And in each case, instead of forming free Civil Society — that is, people capable of influence in a medium, of adding ideas, of generating changes, of being agents of development — it constructs privileged people with fear of losing their privileges.

It is difficult to understand the complete picture, but it is a reality that is happening in Cuba. These reforms, in the law do not recognize the rights of people, and in practice they function as mechanisms of control by the government that also guarantee its absolute power. And they are sold, to the international community, as a process of false opening and that also comes accompanied by an increase in evident repression. In recent years, arbitrary detentions, beating, intimidation, threats have increased. They have increased for the members of the Christian Liberation Movement, independent journalists, Ladies in White, members of other organizations. It is reality that repression is now greater, at the same time that they sell these reforms as a process of opening; with the intention of cleansing the image of the Cuban government, with the intention also of doing business with the European Union, the exiles in the United States, with Latin America.

We cannot be absolute, certainly one sector of society has benefited, at least it has increased the number of people who have access to those privileges — which should not be privileges because they are rights. In any case it is a strategy of the Cuban government for the exterior; it is not a commitment to the well being, development and democracy of the Cuban people. For Cubans there is no real change, there are no rights, there is no possibility of self management. Before this lack of options that represents the Cuban government for the Cubans, before that absence of offers and that increase in repression, the oppositions rises with the Way of the People.

Is Project Varela alive?

RMP: Project Varela has more than 25 thousand signatures with picture identification in the National Assembly; but by having so many more sympathizers, it has many more signatures. The process of verification is so complex that they cannot deliver them all. Because each signature that arrives at the National Assembly is a signature gathered and then verified and then acknowledged, before being delivered to the Assembly.

Project Varela has a series of steps. The first was the presentation in the National Assembly, the second was the presentation of the signatures that guarantee the initiative; and the third was a response that has not arrived. And that response is holding a plebiscite. After there is a plebiscite, there will be another step, the elections. There was a split regarding the intensity of the demand for the plebiscite. By a government strategy, which was to incarcerate the leaders of Project Varela. And well, it is all a marketing strategy, that evidently affected the development of the Project. But what is a fact is that the rights Cubans are demanding through the Varela Project, are rights they still do not have. What is a fact is that the government is violating its constitution because it has not held a plebiscite.

Therefore, what it is about is the holding of a plebiscite. And now it is about that the government is trying a false transition. Now it is about that Cubans have a level of higher awareness about what is happening. There is an awakening of solidarity and understanding with the Democratic Cuban Movement, inside and outside of the country, through which we are all making the same demands. There is a preliminary step in which we find ourselves that happens by the recognition of rights. Cubans of course want to eat better, they want to enter and leave the country; of course they want to live better. But Cubans also understand that for that we need rights. We need self management, because we have the capacity, the imagination, and we are sufficiently hard working to design the prosperous and happy country that we want. And we understand that for that we need rights.

With a dictatorial government that does not permit you self management, well you simply cannot be happy in your country. You do not have all the means that you need for the search for human happiness and not survival. That’s why this is the moment to have a plebiscite. This is also the moment because we may be in a time of false transition. We are in danger of becoming Russia or China or any other aberration that you might think of: a change without rights, is not a change. It is also the moment for the international community to react on the basis of the demands of the Cuban people, and not on the basis of signals sent by the government.

In Cuba there have been no free elections for 60 years, therefore, the Cuban government is not legitimate. That does not mean it has no authority. The dialogue that we are proposing takes into account the Cuban government. Why does it take it into account? Because the Cuban government is the authority. Legitimate or not, it is. And what we cannot do is divorce ourselves from reality.

The Way of the People is much wider, the transition is much wider. The Varela Project is one step inside the Way of the People. Although it appeared before: the Varela Project is a legal, concrete tool; that of course has great implications: political, social, for the life of Cubans. But it is a first step. The Way of the People is the platform that solidifies all the efforts of its actors, that are the major part of the opposition of the Democratic Cuban Movement, inside and outside of Cuba, for a peaceful transition and for changes in Cuba. Somehow it orders them, but in any event it is not written in stone.

It is here to concentrate the unity of the Cuban Democratic Movement in terms of its objectives. And it is also here to serve a little as a road map, but a road map that can be transformed, modified, enriched as needed, also on the basis of proposals that are put forward. One of the strategies that the Way of the People proposes is the promotion of legal changes that guarantee rights. That’s why the Varela Project may be added to the Way of the People, as other initiatives that claim the same rights may be added. The Heredia Project, like Project Varela, is an initiative of legal change. That is to say, the Cuban Constitution gives the possibility to the citizens of making legal proposals and presenting them to the National Assembly. What does the Constitution also say? That if the legal proposal is supported by more than 10 thousand citizens with the right to vote, something that in Cuba is acquired with photo identity, then in this case a plebiscite is held. To ask the people: Do you want or do you not want these legal changes that Project Varela is proposing?

Project Heredia is guided by the same legal strategy; taking the Constitution into account, it proposes a change in the law. Project Varela has five points: freedom of expression, freedom of association, liberation of political prisoners, the possibility of having private businesses, and free elections. Each of these points corresponds to few legal proposals, that have also been enriched with the presentation of laws; for example, in the National Assembly there is an Amnesty law that is presented in the thinking of the Varela Project’s point that speaks to the liberation of political prisoners, as will be presented a Law of Association, as the Varela Project contains a small Electoral Law that can also be expanded because Cuban electoral law is a joke in bad taste.

Project Heredia has a series of chapters that may go to more daily needs of Cubans, like: freely exiting and entering the country, free access to the internet, free movement, in other words, that we Cubans cannot be called “illegals” inside our own country, that they end domestic deportations; also like the recognition of citizenship rights of people who are in exile, and their children, who are as Cuban as those who live in Cuba. They also have in mind some fears of Cubans, as is the case with what is going to happen with property in Cuba at the time of the transition. Project Heredia proposes that the properties that have a social use, or people’s homes, be respected. Because Cuba changes, I cannot take from you the house where you maybe lived for 20 years, although initially it may not have been yours. It is a measure that of course implies waiver and generosity.

It is also a fact that the government in transition has no money for repairing the damage or compensating for 54 years of theft by the Cuban government. So there are some waivers that we must make, and that is one of them. There are points about which we have to be very clear, and one of them is that no family will have to leave its home just because Cuba changes. But there is one very curious thing: Project Heredia as proposed by law is delivered in the year 2007; after the year 2008 a series of reforms begins, and these reforms are touching almost one by one the points of Project Heredia.

Namely, that they partially fulfill what Project Heredia says, but avoid delivering rights to Cubans as demanded by Project Heredia. They implement migratory reform in which they can say yes: they repealed the exit permit, but that does not mean that Cubans do not have to seek permission to leave because they have to seek permission to get a passport; that if Project Heredia is accomplished, these requirements would be illgal because it is planned that there will not exist a conditional right to be human beings, to be children of God, to freely enter and leave the country.

That is to say, in Chile, Chileans could enter and exit the country, they could have businesses, they could buy cars; the Spanish, they could do they same with Franco and at any rate they held a plebiscite and that led to a transition. Because we human beings need all rights; and we need — besides food — liberty.

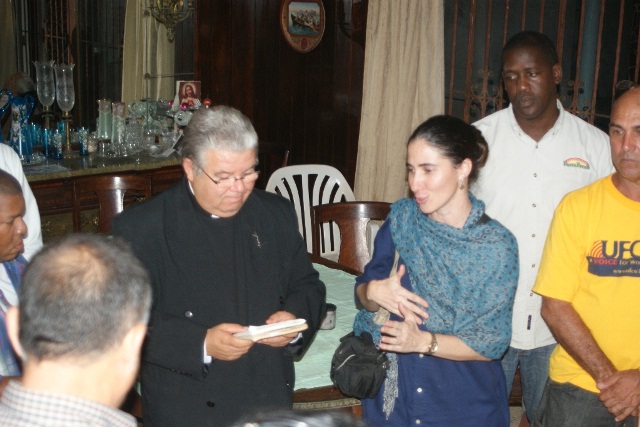

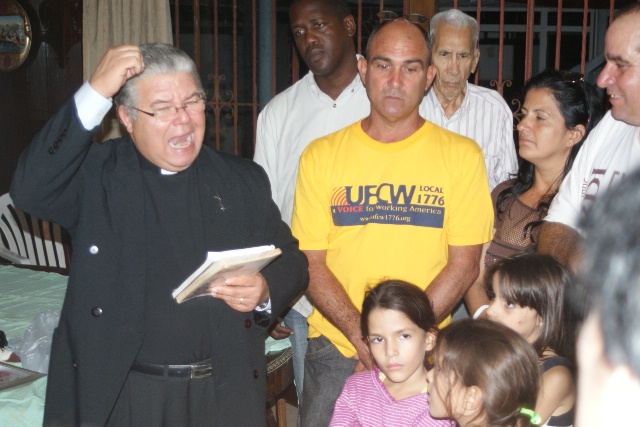

Have you received sufficient support from the Catholic Church in Cuba?

RMP: I believe you have to differentiate what is the Catholic church: The Catholic Church is also me and it is you. To differentiate what is the Church from a certain sector of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, that we understand that they have positions that are almost complicit with this Fraudulent Change.

The reality that I have experienced with regards to priests, nuns, laity, who have lived as Cuban people, that have suffered with the Cuban people, and they have the same desires for change as the Cuban people, of solidarity, of accompaniment; shelter, understanding, and that also is the Church in Cuba. I can tell you that the Ladies in White — when they came to see their husbands: those who lived in Las Tunas to Pinar del Rio; and those who lived in Pinar del Rio to Santiago de Cuba — they stayed in the home of nuns and priests all over the island. That is, it has been the Catholic Church standing with my family, and also with activists for human rights in Cuba, that is what I have experienced.

It has been something fundamental for me, and it is something that deserves to be recognized. As we also see a certain divorce from reality that may not be the intention, but is what can be interpreted also from certain positions that some publications in the Havana hierarchy have taken, that suggest complicity, or at least a communion, with this strategy of Fraudulent Fraud by the Cuban government.

How has the behavior of the authorities been on your return to Cuba?

RMP: Right away you notice that there is tension in their faces, that they know what is happening, but their response was: “Welcome.” And everything was very quick in the airport. They have been, of course, watching us, stalking us in a less evident way. Two members of an organization showed up very quickly. We agreed to the appointment by telephone. One of them sat in the living room to converse with me, and as he had come by motorcycle, the other boy who came with him stayed outside. A short while into the conversation we have a patrolman at the door asking for documents of the two, and asking for the motorcyclist’s papers. Something totally artificial because patrolmen don’t go through backstreets asking for documents.

But there was a threat on a blog. . .

RMP: On the Cuban Herald blog, of the many that the Cuban government has in order to send its messages in a way “not so official.” Although we are familiar with and know how official they are. A threat as concrete as: “We are going to put you in prison.” But always with the same style, with that style reminiscent of criminality. That is to say, within the law, within the right, you do not threaten; you say things concretely. It’s like what happened in the United Nations: “This mercenary that has dared to come here;” it’s not spoken that way.

The authorities should not speak this way. Here they let you see, even using the law, an undertone of criminality, of impunity. Of course it is a direct threat and against me personally and against my mother. What they do not dare to do now by phone, what they have decided now not to do directly, they do publicly; using the unjust law that they have, the law that in many senses is criminal because it is not based on rights but on the repression of rights.

From Cubanet, March 31, 2013

Translated by mlk.