The Cachita of Central Havana / Iván García

In September, Havanans venerate three virgins: on September 7 the Regla virgin; the following day the Virgin of the Charity of Cobre, and the Merced virgin on the 24th. Regla and Charity are mixed race, and one of them, Our Lady of Charity of Cobre, is the Patron Saint of Cuba.

In September, Havanans venerate three virgins: on September 7 the Regla virgin; the following day the Virgin of the Charity of Cobre, and the Merced virgin on the 24th. Regla and Charity are mixed race, and one of them, Our Lady of Charity of Cobre, is the Patron Saint of Cuba.

Rain or shine, Havanans gather on September 8 at the church that bears her name, a construction from the 19th century, painted white and yellow. For some time, a procession passes through the streets outside on this day.

The temple is located in Los Sitios, a neighborhood of poor, black, marginal people in Central Havana. It is a few miles around and from everywhere you can see overflowing trash containers, sewage running in torrents, and a frightening odor of shit that emerges from the cracked and filthy tenements.

The area is one of the most densely populated in the city. In miserable shacks, and high houses propped up on stilts with twisted iron balconies, innumerable families live crowded together, many consisting of “Palestinians,” citizens who come fleeing the extreme calamities of the Eastern provinces.

Almost all are living in Havana illegally. On the day of Cachita, as Cubans call their patron saint, the easterners carry the devotees in their bike-taxis. And they charge double. And they aren’t the only ones making a killing. One woman in dark glasses reads the cards for one convertible peso (less than a dollar). Other neighbors sell roasted peanuts, homemade candy, and bread with thin slices of ham and cheese.

With so many people crowded together the “choros” (pickpockets) take advantage of the least chance to grab a wallet from a pants pocket or a backpack, looking for money or anything of value. A black-haired young woman flies into a rage at an older man who for some time, according to her, had been pressing his penis into her ample buttocks. She threatens to call the police and the guy disappears.

The police, of course, flood the area around the church. The State Security agents keep their distance with their short hair, Motorola cell phones and Suzuki motorcycles.

Tourists usually show up with video cameras. A well-built black boy hugs his Spanish girlfriend. Hookers dressed in the latest styles try to make it inside the church to put a roll of coins on the altar.

The priest announces that the procession is starting. The figure of the virgin is taken out in a class case and mounted on a convertible car.

The crowd starts to move. Some are praying and some are drinking rum and beer. Others eat peanuts and chew gum. They take photos and record videos. Although perhaps only once in their lives, Cubans go to this church to pay tribute to Cachita. It doesn’t matter that her Havana temple is surrounded by poverty.

Fortunately, her real home, in the Cobre Sanctuary, in Santiago de Cuba, is located on a beautiful place surrounded by mountains.

Translated by RST

September 15, 2010

A Region of Cafés con Leche and Pork Rinds / Ernesto Morales Licea

Is there any lesson Latin Americans can take from the recent appalling events in Ecuador, where a group of mutinous police, demanding the repeal of a law affecting them, kidnapped and physically assaulted the president of the Republic?

I believe so. I think that incidents of this nature have a radius of action a hundred times greater than the simple context in which they occur, and they shed a very clear light on certain practices that concern not just a handful of citizens, but an entire region.

What took place in Quito last Thursday has, in my opinion, an exact definition: embarrassing. Allow me to set aside the definitions of legality, democracy, constitutionality, because in truth, the feeling generated in me — as a television viewer and ultimately a Latin American — by this Hollywood spectacle of kidnappings, mobs, nocturnal shootings and risky rescues, was just that: a deep shame.

In the first place, what is the origin of this political riot that could evolve into a coup d’etat (although I differ with those who say that was the original objective)? It was the discontent of an important sector of the Ecuadorian national police with the passage of a Public Service Law which did away with certain benefits — salary increases and bonus rewards for years of service.

The impending loss of these benefits had already caused those affected to hold negative opinions (reaction rather than logic), and in order to discuss the new uses of the dollars saved, and the fairness of the measure, the Ecuadorean president had gone in person to the Police Headquarters in Quito.

The final outcome of the presumed dialog was physical aggression not only against a leader — who, whatever people say, enjoys wide popular support in his country — but who is also a human being who was recovering from an operation on his right knee.

They used tear gas against the president. They insulted and attacked the president. They confined him at the Police Hospital and for twelve feverish hours held him hostage along with some of his closest aids and political appointees.

The demand from the insurgents remained the same: “You abrogate this law and we’ll stop everything,” was more or less the offer of his captors.

Now, the first question that could be asked about this act of social barbarism is: What kind of confidence can Ecuador have in its institutions, after one of the most visible, and by definition the one charged with ensuring public order, engaged in such an uncivilized and violent act?

At that moment, trying to mentally weigh the impact of what I saw on television, I remembered a brief social essay by Mario Vargas Llosa. It was titled, “Why has Latin America failed?” One of the fundamental ideas that great writer (in the past also a politician) defended was that there cannot be sustainable democratic development in our region while our institutions continue to be so greatly discredited, and while the people do not really believe in them.

I subscribe to this statement one hundred percent. How can Latin Americans achieve a prosperity that is not only economic, but also social and cultural, while the institutions created to safeguard the functioning of society behave themselves, at times, like legalized gangsters?

Latin Americans cannot have confidence in a renewal process while the judges who make the laws are officials who can be bought and sold (Mexico: case in point), or puppets who distort the law whenever their government master demands it of them: See Venezuela.

How can we pretend to elevate our region to a more respectable and dignified status in the eyes of the world, if the police are more corrupt than the narcotraffickers, and common citizens often don’t know who to fear more, the criminals or the supposed agents of public order?

How can Latin Americans have even the slightest level of self-esteem, when it has been more than a practice, and in fact a tradition, that the armies overthrow the presidents (just or unjust, democratic or totalitarian) and bathe in the blood that flows in the streets of their own countries?

This was the first conclusion I came to in the new case of Ecuador: the state of health of democracy in Latin American continues critical when a vital institution like the police believes it has the right to attack the highest authority of the nation, and present its demands as it would to any headquarters colleague.

Those responsible for these institutions can perhaps be replaced, but social awareness is not so easily replaced.

Another important point to consider is the speed with which so many leaders in our region rushed to ridicule an incident of this magnitude.

Me, although I am not even remotely a politician, understand that moderation and tact — when the pieces are not yet clear on the board — are primary in this profession.

Meanwhile, two presidents whom I don’t hesitate to define as the most lamentable in Latin America today — Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales — lost no time in making themselves the laughingstock once again, this time with the crisis in Ecuador as their stage.

The first was comandante Chavez, whom I remember cynically saying to Jaime Bayly in a television interview in 1997, before his investiture as president, that should he win at the ballot box it would not “go badly” for foreign investors, that he would respect private property and freedom of expression, both so necessary in his country.

Well, this current paradigm of governmental arrogance didn’t hesitate for a second to shout that the United States was the real orchestrator of this coup, and he repeated it a few more times, in case the grinning Amaryan who administers Bolivia wasn’t listening closely to what he should say. Evo heard, of course, and repeated it like a faithful clone.

With almost the same alacrity as the rest of the denounced governments, the United States officially and in no uncertain terms denounced this act against the president of Ecuador.

Not even the Cuban government dared, this time, to accuse the Americans, at least publicly, of being behind this incident. Nor has the one principally affected, Rafael Correa, who at other times hasn’t hesitated to confront U.S. policy hand-in-hand with his allies Chavez and Evo. But those two, one as the voice and the other as his echo, were consistent in their perennial effort to be the least respected presidents in our hemisphere.

I think this act of police insubordination in Quito, still offers us material for analysis. It will come to light whether — as Rafael Correa claimed from the outset (also unwisely and without proof) — the ex-president and coup leader Lucio Gutierrez had a hand in it, or if it was simply an event coordinated by the dissatisfied police.

Partisans of both hypotheses can say what they will, but there is no clear evidence that event was limited only to discontent among its participants, nor that it was an attempted coup where Gutierrez took an active part.

But what we can already take away as a definitive lesson from the attack suffered by a president in the exercise of his mandate, on the part of the police facing the loss of some of their economic benefits, is that a great deal is still left to be accomplished in Latin America to build First World countries, not only with regards to economics, but also mentally.

A typically Cuban anecdote related that a well-known politician, during the presidency of Tomás Estrada Palma at the beginning of the Republic, could find no better way to describe Cuba’s battered civil spirit than to say, “This is a country of cafés con leche and pork rinds.”

Offensive but true: Latin American nations, with such a tradition of blood and brawls, where three coups can happen in the same country in less than a decade, where the tradition of putting dictators in power is not dead, and where in the 21st Century a president can be slapped for taking away benefits, has not ceased to be, with a few exceptions, a region of cafés con leche and pork rinds.

November 21, 2010

The Carnival of the Dead / Yoani Sánchez

The rumba sways from side to side as the partying cuts across the Havana Malecon in a summer that makes you use your shirt sleeves to wipe away the sweat. From the eighth floor of a nearby building, a man can no longer hear the congas and the drunken shouts. His thoughts come with bursts of machine gun fire and the smell of a distant Africa where he lost a friend, sanity, and sleep.

Ariel is the main character in The Carnival and the Dead, the latest novel from Ernesto Santana, an authentic writer of shadows in a blacked-out city. For those of us who already know his writing — harsh, accurate and loaded with questions — this new novel reacquaints us with a daily venality now so common that we hardly see it anymore. He draws us into the trauma of those who were taken to distant lands to wage a war they didn’t understand, one that still, today, many of us cannot comprehend. It is a story of love, ghosts, HIV, and other characters in this drama of just 175 pages. A fiction of the dead who leave and return, of specters in their epaulets and medals, soaked in alcohol, needing to forget, urged to throw themselves into the void. In short, a book in the most intimate and raw style of the winner of this year’s “Novelas de Gaveta Frank Kafka” literary competition, Ernesto Santana.

Shortly, in our home on the fourteenth floor of a Yugoslav-style building that could well be in any part of Cuba, we will be presenting this horrifying and indispensable work. Neither triumphalism nor despair will be welcome.

December 3, 2010

The Departure of the Patroness / Ernesto Morales Licea

My mother contracted the debt in my name, and hours later made me aware of it. She said:

“I promised the Virgin that you would go today to her leave taking. At seven in the evening they are taking her to another community, so do not wait too long to go.”

For a deluded second I tried to evade the obligation. I tried, for example, to say “I already have a commitment, you didn’t tell me far enough in advance,” but I gave up immediately. There are certain requests from mothers that, although they are camouflaged as mere suggestions, have a military strength. You comply, and talk about it later.

So there I was, at the parish of San Juan Bosco as night fell in Bayamo, docile before a debt I did not contract and did not have much interest in settling: I have never confessed it, I haven’t even wanted to think about it in a conscious way, but since April 2009 I’ve experienced something like a vague resentment toward the Virgin of Charity.

A family member whom in life I loved with a passion, was murdered by two savages who, in doing so, also forever made off with piece of my joy. At the moment of death, as the worst criminals had done at the time of Christ, my uncle, paradigm of the greatest virtues of my blood, carried the Virgin on a card in his wallet, and on a gold pendant around his neck.

From that time on I, spiritual by definition but rational and atheist by upbringing, could not think of the national deity with the same emotional respect.

So what was this leave taking to which my mother sent me? It was the farewell to Bayamo of the statue of the Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre, who has been making the rounds of all the provinces of the country since August. The primary way in which the Catholic Church has wanted to pay tribute to the Patroness of Cuba on the 400th anniversary — coming up in 2012 — of her appearance in the Bay of Nipe.

According to the legend, this tiny Virgin appeared in the midst of a raging storm, floating atop the waves, to protect three helpless fisherman who had no other option than to offer themselves up to heaven. Some say the image came from the shipwreck of a boat that carried it, and that explains its appearance in the water. Others speak of the divine.

What is known is that she appeared in 1612, and since then the Virgin de la Caridad del Cobre has been the patron saint of the nation, boasting another even more glorious title: The Virgin Mambisa. Our patriots of the 19th century carried her to their encampments and venerated her in the midst of enemy fire.

They embroidered her image on their shirtsleeves, and gave thanks to her when they returned alive from the battle with the Spaniards. Now, commemorating her four centuries, the ecclesiastical authorities have taken a replica of the original (which is jealously guarded in Santiago’s El Cobre) and is presenting her to all Cubans.

She arrived in my city a few days earlier from Holguín. According to testimonies from my friends, her reception in Bayamo was really an apotheosis. They spoke of twenty thousand people following here through impassable streets, and masses overflowing with humble parishioners. Now she continues her journey.

Two blocks from San Juan Bosco Church I could barely move. Neither the anomalous cold of this warm region, nor the evening rush prevented many thousands of devotees from coming to see her go.

This more personal, more intimate contact, with the keeper of a faith rooted in the religious and cultural consciousness of a nation, offered a perfect opportunity for the consecration of the faithful, and for those who also had something to ask, but didn’t even know how to do so. This was confirmed for me by an amusing question from the priest who officiated at the mass:

“How many of you are coming to our parish for the first time? Please raise your hands.”

A multitude of hands, amid a whispered camaraderie, rose above our heads. My arm among them, of course. Many did not know how to pray, had never attended a mass, and as was evident in their faces, they found themselves confused, faintly blushing, to be in a temple that had, until then, been something foreign and distant.

But now that the Patroness was within those resonant walls, there was a particular feeling, one of hope, that extended from that religious altar; it was a time to abdicate disbelief and to ask the divine for what cannot be reached on a human plane.

I saw emotional faces. Hands joined together, eager eyes. I heard murmured prayers carry the dreams of those who wait and suffer. I saw the sick, the crippled, the malformed, faces martyred by physical or spiritual pain where only in a congregation like this one could they find a glimmer of peace. I saw friends with unmentionable plans, with obstructed paths, with material needs transformed into spiritual anxiety. I heard prayers for the imprisoned, persecuted, humiliated. An infinite set of ideas and people.

And all, everyone who presented themselves before this beautiful and humble figure, delicately naive, experienced the most harmonious and conciliatory moment of their recent days.

I remembered the aura of solemnity and the faith in the impossible that emanates from the temple located in El Cobre, where Cubans of every ideology, race, nationality and religious creed, at some point finally arrive. Some, to repay sad promises on their knees; others to give the Virgin their Olympic medals, their university degrees, or their crutches; and others, like me, out of elementary social or cultural interest.

I think back to my home, full of photographs and mental images, I did not understand how mysterious is the terrain of faith and human sentiment. I knew, though, that this show of brotherhood, its energy spread by a voluntary multitude, none of whom were summoned or forced to do anything, who in other times had held firm to their faith despite persecutions and exclusions, was indisputable proof that people can be deprived of all their liberties, except spiritual freedom.

And if I could not come to discover my faith before an image created by human hands, dressed by humans, devoutly carried by humans, I could enjoy the event as a sociocultural phenomenon that identifies and defines us, but that I cannot sensorially partake in; and so perhaps I should look with humility on all those Bayamese who asked for their lives, their miseries, and their desires. And who did it with real passion.

Now that an untimely Hodgkin’s Lymphoma forces me to write from a hospital nearly five hundred miles from home, and threatens a radical change in my life as a healthy and future-oriented young man, I can’t help but envy those who attain such spiritual communion and find in her solace and peace.

December 3, 2010

The Road to El Rincon / Rebeca Monzo

Once again this year, our friend, who does not like to go backwards nor drive long distances, invited us to take her in her car to El Rincon and back again, to lunch in a very good paladar – private restaurant – in Santiago de las Vegas, as a gift for my birthday

Once again this year, our friend, who does not like to go backwards nor drive long distances, invited us to take her in her car to El Rincon and back again, to lunch in a very good paladar – private restaurant – in Santiago de las Vegas, as a gift for my birthday

We left about 10 in the morning to allow a little time in the sanctuary and to investigate a bit, on the way back, looking for onions, as they are very rare and expensive in the city.

I noticed, with pleasure, that after a year, those broken roads had been repaired. We hypothesize that it was because of the proximity to the upcoming Saint Lazarus’ day.

During the trip, we were able to observe that many people were walking from the last bus stop in Santiago de las Vegas. Others climbed aboard carts pulled by pairs of horses, carrying twenty people. It was almost a medieval vision. Improvised flower stalls were on both sides of the road, and in the doorways of some of the houses were tables full of plaster images representing Lazarus, Chango, and some other deities. Also the odd stall selling pork, just hanging there, without any refrigeration. The day was cloudy but very hot.

During the trip, we were able to observe that many people were walking from the last bus stop in Santiago de las Vegas. Others climbed aboard carts pulled by pairs of horses, carrying twenty people. It was almost a medieval vision. Improvised flower stalls were on both sides of the road, and in the doorways of some of the houses were tables full of plaster images representing Lazarus, Chango, and some other deities. Also the odd stall selling pork, just hanging there, without any refrigeration. The day was cloudy but very hot.

The most pleasant surprise was upon arriving at the church. Newly painted, and with very well tended gardens. I immediately noticed the absence of the sign that was on the front door last year, spelling out some of the prohibitions with regard to dress and conduct, for those who wished to enter the temple. The church was filled with believers, despite being almost twenty days before the awaited celebration. Many young people and children, as well as a large line of people of all ages, were waiting to receive the blessing. The altars of Lazarus and the Virgin of Charity were filled with flowers and candles. A young woman dragged herself to the altar, fulfilling a promise. I was extremely comforted to note that, despite the years of prohibition and shortcomings, the popular faith is growing every day.

Translated by ricote

Translator’s note: December 17th is the day of Saint Lazarus, the Patron Saint of the sick (also known in the Afro Cuban culture as Babalu Aye). Pilgrims come from all over the island, some crawling hundreds of miles, to the Sanctuary of Saint Lazarus, in the El Rincon neighborhood at the southern edge of Havana.

November 28, 2010

The Untouchables / Ernesto Morales Licea

As always, a macabre joke summarizes a Cuban reality with unsurpassed accuracy:

As always, a macabre joke summarizes a Cuban reality with unsurpassed accuracy:

Three guests of different nationalities celebrate the courage of certain practices that take place in their countries.

The Dutchman says:

“Brave men that we are, we went in a group to find prostitutes, knowing that among them, it is almost certain that one has AIDS. And the one who sleeps with that one… well, you know.”

The Russian says:

“Brave men that we are, we are the ones who invented the game of Russian roulette. We gather to drink vodka and put one bullet in the revolver. Everyone has to put it to his head and pull the trigger, and the one who gets the bullet… well, you know.”

The Cuban, amused, dismisses them all with:

“Brave men that we are,” he says, “we meet on any street corner to speak ill of the government, knowing that at least one person in the group is State Security. And whoever’s turn it is to get fucked that day… well, you know.”

Neither art nor television have escaped the pervasiveness of this institution in Cuba; and it’s the same for fictionalized series that have been the work of heroic infiltrators; they have managed to produce clandestine films like the short Monte Rouge, directed by Eduardo del Llano (a truly national “underground hit”), where, as the height of cynicism, two security officials knock on the door of the citizen known as Nicanor and smilingly inform him that they have come to install the two microphones allocated to his home.

The truth is that few factors have done as much to shape interpersonal relationships in Cuba as this organization, whose ultimate purpose and essence is, in many case, betrayed by its own members.

That is, the term “State Security” should imply, in any society in the world, an element of tranquility, a civil guard, and a collective justice. The intelligence services are, by definition, indispensable for national protection against aggression or criminal activities of different kinds.

In Cuba, it is an undeniable fact: unlike the rest of the institutions that incompetence has gnawed to the bone, State Security works flawlessly. All you have to do is look around you to see it demonstrated.

They do exemplary work in detecting outbreaks of drug sales, prostitution or child molestation, reprehensible crimes in any modern society. In the recent painful events of the overdose of a child victim in Bayamo, this agency played a vital role in the investigation and clearing up of this monstrous case.

Nor can one deny the merit of having avoided many possible deaths from attacks that presumed “anti-Castro fighters” (a subject on which I will write soon) have launched against the Cuban people: explosions in hotels, nightclubs and public facilities, introductions of pests and diseases that are unacceptable from any perspective or ideology.

So, speaking of State Security on the island is neither idle nor vain, and an honest person should recognize that their work — admirable, heroic, protective of civilians — is worthy of laurels.

But, if everything ended there, this article would not exist: for unpalatable and unipolar themes we Cubans already have the newspaper Granma.

Because what is lamentable and needs to be decried to the four winds is that this institution, so useful in other places, has long since become a ghost of national security, a shadow of subtle repression that corrodes and conditions the reality in which we live.

When in Cuba one thinks of State Security, one immediately and inextricably associates it with the persecution of political dissent, its first and most important function.

No other mechanism has generated more “anthropological damage” in post-revolutionary Cuba, than this organ which at times has become a paradox in itself: nothing has been more of a threat to the personal safety of Cubans, than this.

Why? Well, because popular knowledge of its practices, its undetected and unpunished methods, its unlimited reach, have generated a pathological fear in us, leading to the development of a defense mechanism as effective as it is lamentable, hypocrisy.

Cubans never dare to act out, publicly, their true thoughts on a political issue, when they dissent or have views contrary to the official ones. These topics are talked about in whispers in the privacy of one’s home or among one’s closest circle.

But even then, we are always suspicious, glancing from side to side, muttering under our breath. The joke with which I began this post is not hyperbole: we all know that among us, the informant is never missing.

The ubiquity of this body is frankly beyond paranoia. It is immeasurable. If one day we Cubans have access — as happened with the archives of the Stasi after the fall of the Berlin Wall — to the documents that reveal the number of agents, officers, infiltrators, and dedicated or casual informants, I think the figure should be forgotten in the interest of salvaging our national pride.

There is no school, bakery, philatelic association, farmers market or baseball team that does not have, among its membership, someone belonging to this “glorious” institution. At times, who they are is even more or less public knowledge. For example, every public institution has a comrade from Security who pays attention to you and that comrade is at times well known.

We Cubans have learned to live with an intelligence apparatus, oiled to the point of maniacal precision, which maintains its operations in the shadows as it sees fit, and that also, when it sees fit, makes use of any arguments provided by its informants to dismiss thousands of employees, imprison opponents or, even more common, to discredit the morals of non-conformist citizens.

The worst side of this reality is that we have no way to defend ourselves against this action. That is, all citizens know that their phones can be tapped, their homes may be searched, that their electronic communications are reviewed and stored, that their lives are examined with a magnifying glass, but there is not a single legal way to fight this. State Security in Cuba has an Olympic impunity: its members are our Untouchables.

So it’s no wonder that the advice most often repeated to those who express more or less publicly their disagreement with Cuban politics is: “Don’t talk so much, you don’t know who is listening.” A phrase so reviled, but one which captures a vital reality: the same person who is listening to you, or provoking supposed disagreements, the same person who accompanies you every day, who works by your side, who shares drinks and music with you, the same person you confide in with a blind passion, could quite naturally be the informant who has stayed by your side to know, in his game of chess, when the time comes to checkmate you.

Many times I’ve been personally entertained by the black humor of general mistrust: friends who insinuate to me, or express openly, their fear that it could be me, the loudmouth irredentist, the new pearl of local intelligence. In fact, I smile, but with the false amusement of the clown in Beneditti’s story.

For those of us who do not resign ourselves to living surrounded by fear and tropical James Bonds, I believe that a concrete desire, right now, would be if the nationwide mass layoff of workers would also knock at the door of State Security. But to be optimistic in this regard would be angelically naive.

November 21, 2010

Occasional Photos by… / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Who is Arnaldo Ramos? / Iván García

He arrived home on Saturday. After 7 years and 8 months behind the bars of a cell and the creaking of locks, the dissident economist Arnaldo Ramos Lauzurique, 68, at 6:30 in the morning of his first Sunday in freedom, sat in the park facing the modest apartment where he lives in the neighborhood of Central Havana.

He wanted to watch the sunrise, breathe the fresh air and see ordinary people carrying plastic bags for Sunday shopping. He wanted to feel like a free man. After two hours of meditation, the sun began to warm the Havana morning and the sound of children with their bats, balls, skates and soccer balls, broke through his personal spell.

Then Arnaldo Ramos began what was always his daily routine. Joining the long line to buy the official press in a tobacco shop. It is one of his hobbies. Collecting the daily papers and filing them in boxes.

“When I was arrested on 19 March 2003, it was around 9 in the morning, and State Security spent five hours demanding papers and documents,” he says sitting in a mahogany chair.

Ramos, a thin mulatto, short in stature, is well preserved. He is hyper-kinetic, with a fixed gaze and acute analysis. His apartment is furnished in a Spartan style. For the last 45 years he has been married to the doctor Lydia Lima, who is now retired. He is the father of two, with two grandchildren.

He has an extensive history as a dissident. Like other leaders of the current opposition, in the first years of the revolution he had hopes for the project of Fidel Castro. Before realizing they were applauding a fraud, Arnoldo worked in that factory of technocrats that formed the central planning board, JUCEPLAN, an institution that governed the island’s economy and ordered the number of boots, combs and toothbrushes that were to be fabricated every year.

“After graduating in economics in 1971, I started working in JUCEPLAN, with the cream of the economic gurus of Cuban socialism, like Irma Sanchez and Humberto Perez. There I lived, in its entirety, the financial lie, how to doctor the figures to coincide with the interests of Fidel Castro, who skipped all the rules and when some plan occurred to him, however crazy, he sent the draft and the agency had to carry it out to the letter.”

His first problems with the system began with the economic analysis done for the JUCEPLAN newsletter, in which there were some underhanded criticisms. “It was the era of the billions of rubles that the USSR sent us. Waste and improvisation. Burying money in imaginary projects or making purchases in the capitalist countries with super modern factories, which did not accord with the logical development of the country. I remember that in 1978, when thousands of taxicabs were purchased in Argentina, I made the report without ever having traveled to that country,” said Arnaldo, while sipping a powdered orange soft drink .

By 1987 things were already clear to Arnaldo Ramos. The economic system, including the political system, was not working. In 1991 he retired. The following year he began working with another dissident economist, Martha Beatriz Roque Cabello. Together they organized an institute of independent economists. “In 18 years in the opposition, my main contribution was theoretical: to dismantle the government’s complacent discourse and point out the real background of the supposed economic successes.”

On a leaden gray April afternoon he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for insisting in his articles, studies and investigations that the Cuban economy was heading towards the ravine.

Seven years were very hard for a person who was already 60. “Except in Holguín prison, where they beat me, I did not receive physical punishment. Harassment and verbal abuse, yes. It was also a punishment for my family, who had to travel nearly 500 miles loaded with crates, to visit me. Still, I never thought to leave my country.”

He was in two of the toughest prisons on the island. That of Holguin and Nieves Morejón, in the province of Sancti Spiritus. In the past six months, the authorities transferred him to 1580, a prison on the outskirts of Havana.

He was released on parole, a sort of legal limbo that technically allows the government to send him back to jail whenever it wants.” An official of the State Security told me I was free to engage in any activity, and they would not imprison me again. But that was a verbal commitment. There is no document that confirms that.”

Of the alleged economic reforms of the government of General Raúl Castro, the independent economist does not expect anything positive. Nor does he believe that anything important will come out of the Sixth Communist Party Congress, scheduled for April 2011.

The one thing of which he is indeed convinced is that profound changes must occur in Cuba in order to make a leap forward in the economy. And Arnaldo Ramos will be one of those voices for change. Count on it.

Text and photo: Ivan Garcia

Translated by ricote

November 25, 2010

Detainee 1262: Cell 16 / Luis Felipe Rojas

It was Saturday, November 27, and we left early for Guantánamo. At 12:40 pm we were at the control point known as Río Frío, a few kilometers from the city of Guaso.

When the police stopped the vehicle we were riding in, they asked me urgently for my identity card, as well as that of the driver, and under the burning Eastern Cuba sun, they used the pretext of checking the vehicle.

My son, Malcolm, who is 7, started to vomit from nausea and lack of food. Some police approached, one of them looking a little embarrassed, but they kept us there a few more hours. At 3:00 pm a G2 official came and they put me in a patrol car and took me directly to the operations unit. A slight altercation left me with a scratch on my forehead and bruise on my arm. The rest was a mere formality. They left my wife Exilda behind with the children. In Guantánamo, Rolando Rodriguez and his wife Yanet Lobaina were waiting for us, because they we were to be the godparents at the christening of their three children on Sunday, the 28th. This was the first time I heard of a Catholic baptism being prohibited in the last 20 years. I was left with the face of my son, Malcolm, as I said goodbye to him, handcuffed in the jeep.

1263

Officer Ramirez told me, “You are number 1263.” To which I answered, “Let’s be clear about this, I won’t respond to that number.” The rest was the anxiety of imprisonment and good conversation with my comrades in the cell. I had to explain to them that I am one of those who is politically persecuted in my country, and that I could even denounce what was happening with them if they told me their stories, But, still afraid, they asked me not to use their names. So I asked them to choose their own pseudonyms: Alfredo, Raciel and Carlos. On another occasion I will tell you their stories.

From 3:00 in the afternoon on Saturday when I entered the operations unit, I took no food until Sunday night when I drank some orange juice, acidic and lacking sweetness, that they gave me in the snack. At dawn on Monday I drank again, some dark broth that once might have been chocolate. The two nights were a hell. The walls are covered with blood stains, as the inmates entertain themselves killing mosquitoes against the wall, and then with their remains they write their names, note the dates, the time they’ve been there and where they’re from. The toilet gave off its stench the whole day, and I could see that they never sweep the cell. I refused to eat, but I could see the food of the other detainees: watery soup with no flavor, they told me, boiled yellow rice, and a boiled egg, cold and hard.

The night before my detention, three young men from Guantanamo, Abel López Pérez, García Fournier and Yoandris Jordis, had been in the same cell; the first two are political prisoners and prominent activists from the peaceful opposition.

I could see how far the bureaucracy has gone to undermine the lives of Cubans. They wanted me to sign off on my detention, the confiscation of my belt and telephone, the return of the belt and telephone, the warning notice, and the release letter. Of course I didn’t sign a thing.

On Monday at 8:00 am they returned me to San Germán. The whole journey was the opposite of that of Saturday when I had gone with my family. It was a return to the inverse, seeing how my country has been turned into a pack of wild animals who trample the gardens. Forbidding us to attend the baptism of three children, what madness.

December 2 2010

The Cuban Blood of Rubén Blades / Iván García

“Buddy, is it true that the mother of Ruben Blades was Cuban?”, Arian, a 16-year-old student asks me, incredulous. “Cuban and from Havana”, I reply.

On the island, young people know who Rubén Blades is, know his songs and dance to his music. But many are unaware that his mother, Anoland Bellido de Luna-Caramés y Perez, was born in 1927 in Regla, a town just across the bay from Havana.

Since her name was so long, she took the stage name of Anoland Díaz. in addition to being a singer and pianist, she also worked on radio dramas. Myriam Acevedo, now a leading actress in Cuba, knew Anoland as a young child.

“Anoland was also an exceptional child. From childhood she could play the piano like a true professional. She sang soprano and as a child I sang as a young contralto. The owner of the CMQ (the main radio station in the country) had the idea that our two voices could do a duet, and so it was. They called us Myriam and Anoland, the perfect duo” remembers Myriam, who has lived in Italy since 1968.

Anoland was very young in the 40’s when she went to Panama. One night, while performing at a night club, the Cuban woman noticed the man playing the bongo drums in the orchestra that accompanied her. It was Rubén Darío Blades Bósquez, a Panamanian of Colombian and English descent. His work as a police detective did not prevent him from sharing his passion for music and percussion. The couple had five children, and the second was Rubén Blades Bellido de Luna, who came into the world on July 16, 1948 in the San Felipe neighborhood of Panama City.

His paternal grandfather, a native of the island of St. Lucia had gone to work on the Panama Canal, and his maternal grandfather, Joseph Louis Reinee Bellido de Luna, from New Orleans, went to Cuba to fight in the Spanish-Cuban-American War. He liked the country and decided to stay, marrying his third wife, Carmen Caramés, a native of Galicia, with whom he had 22 children, including Anoland, who died in 1991.

The Cuban writer Leonardo Padura swears that Rubén Blades came to music through Benny Moré, one of the greatest musicians that Cuba has given the world. Blades himself confirms it:

“I was 10 when my father took me to see Benny Moré, on tour in Panama. He did that like someone going to see the tallest building in the world, because Benny was unsurpassable. After the blockade (by the United States against Cuba), I found more revolutionary offerings like Juan Formell and Los Van Van, Adalberto y su Son, Gonzalito Rubalcaba in the line of Afro-Cuban jazz (latin jazz). I realize now that Cuba was developing a new and tremendous music. And then it produces a reunion with the contemporary Cuban music, especially starting when Juan Formell and Los Van Van recorded the song, Muévete.”

In the Blades home they also listened to Perez Prado and the Orquesta Casino de la Playa, founded in 1937 and considered to be the first big band in Cuba.

In 1990, to celebrate the 45th anniversary of its founding, the group Clave y Guaguanco, which together with the Muñequitos de Matanzas and Yoruba Andabo played a more authentic rumba, dedicated to Rubén Blades the record Dime si te gustó, which includes three songs of Panama: Para ser rumbero, Tiburon, and Te estan buscando.

When Rubén Blades sang in Havana with the Fania All-Stars, in March of 1979, he was in Regla, his mother’s homeland. The story is in this video.

His mother’s family injected the best Cuban music into his veins, and from his father’s side he received life lessons, especially from his grandmother, the Panamanian Emma Bósquez of Laurenza. “My grandmother Emma was the best. I always said that the worst poverty was spiritual. She was a teacher and writer who painted, and defended the rights of women, a Rosicrucian, spiritualist and vegetarian in the 30’s. It was she who taught me to read and write, when I was 4”, he says.

A lawyer by profession, the career of Ruben Blades has been linked to both music and politics.

In 1993, in an open letter to Fidel Castro, he protested the arrest of the Cuban poet Maria Elena Cruz Varela and criticized Castro’s long tenure in power. More recently, in April of 2010 he said that Cuba’s government “continues to exhibit a level of intolerance, intransigence and fear that is contradictory to its thousand-times expressed conviction that the overwhelming majority of the country supports Marxism-Leninism.”

Translated by ricote

September 13, 2010

In the Spirit of the Congress / Regina Coyula

Only our system is able to overcome difficulties and preserve the achievements. We will update the economic model, yes to planning, no to the laws of the market, economic efficiency, increased productivity. Yes, now we are going to build socialism!

And what have we been doing for the last fifty years…?

Translated by ricote

December 2, 2010

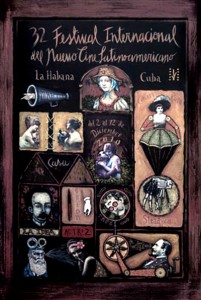

Movie Days / Iván García

The Havana Film Festival starts on Thursday, December 2. The 32nd International Festival of New Latin American Cinema.

The Havana Film Festival starts on Thursday, December 2. The 32nd International Festival of New Latin American Cinema.

The common people, who go without milk in their coffee every day, count the coins in their pockets; during the ten days of the Festival they can put aside the burdens and sink quietly into that dark magic is the big screen.

Year after year, when December comes, Havana is a sea of people and long lines in various neighborhoods of the city. Elena, 54, often asks for days of work and from 12 noon until about midnight, she jumps from one movie to another and enjoys the latest of the Latin American cinema.

Rogelio, 60, a librarian, has just acquired a 20 pesos (one dollar) ticket book for the central Payret cinema. This book will allow him to see 10 films without having to stand in the long lines (each entry costs 2 Cuban pesos, 0.10 cents).

Apart from a lot of movies from the the continent, in this edition, as usual, there will be European productions. You can also discover the new Canadian films or Independent U.S. productions.

Alfredo Guevara, president of the Havana festival, announced in a press conference that this year the festival will showcase over 500 films, of which 122 will compete for Coral awards. Argentina tops the list with 88 titles in the seven categories of prizes. Followed by Mexico, with 79 and Cuba with 78, including four feature films that aspire to win a Coral.

The homegrown films are: The Eye of the Canary, from the director Fernando Perez; Long Distance, by Esteban Insausti; Ticket to Paradise, Gerardo Chijona; and The Old House, Lester Hamlet.

Guevara also confirmed that the 32nd edition exceeds the previous in numbers of films and is distinguished by the diversity of genres. “We approach the days of the celebration of the intelligence and visual art, at this festival with an overflowing loyal following, which is the greatest gift we could have. Already 32 years. It’s a lot,” he said.

More than 20 works of fiction and 24 operas vie for the Coral prizes. Among the favorites are Brothers, by the Venezuelan Marcelo Rasquin, winner of the Colón de Oro prize this year in Huelva, and Abel, produced and directed by Mexican actor Diego Luna.

Despite the poor condition of several theaters and the common problems of public transport, film festivals are always well received by the Cubans. For moviegoers it is a unique opportunity: the rest of the year, movie listings are quite poor on the island.

And for those who do not have the cinema as one of their priorities, is an opportunity to clear their heads, take the wife and go to the movies and eat peanuts or popcorn.

Then, off, to buy a hot dog and watch the sunrise sitting on the wall of the Malecon. One way to escape the economic crisis. It is also in December. Month of wrapping-up. And best wishes.

News From Yamil’s Family via Twitter / Yamil Domínguez

Bread is Screwed Up Everywhere / Regina Coyula

On the program Free Access on the Havana Channel last week, bread was once again the subject of analysis. Viewers called in to say that the bread was sour, insipid, old; adjectives used together or separately. The money, the bread, the ration book, all mixed up. The call that threw them for a loop and wasn’t aired was why there is bread for sale in foreign currency, but there is no government bread.

December 1, 2010