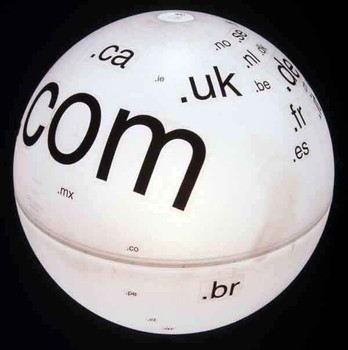

Regina Coyula, 30 June 2016 — For Cubans who update their home entertainment weekly with the now famous, private and anonymous Paquete (Weekly Packet), they are familiar with a subtitle in bright, greenish-yellow letters at the beginning of the movies. This inevitable “http://www.gnula.nu” which comes up so much, piqued my curiosity. It was impossible for me to recognize the country that corresponded to that extension, so I resorted to the always-useful Wikipedia.

Surprise. The country of the pirated movie site that we see at home is Niue, an atoll with airs of a small island, assigned to New Zealand. In 1996, a North American (who doesn’t live in Niue, of course) claimed rights to “.nu” and, in 2003, founded the Internet Society of Niue, which allowed the local authorities to convert the quasi-island into the first wi-fi nation of the world. They supplemented the offer with a free computer for every child. Nothing spectacular; we’re talking about a population of barely 1,300 inhabitants. continue reading

The irony is that the .nu domain generated enormous income, while the inhabitants of Niue not only didn’t enjoy those gains, but also wanted to be connected from their homes and not from the only cyber-café on the island, and they had to pay for the installation and the service.

I also discovered another curiosity. The second extension that is most used on the Internet after .com corresponds to another little place in a corner of the Pacific that few know about, a group of little islands barely 11 square kilometers in size. Tokelau is the name of the place whose domain .tk hatched in 2009, upon offering itself for free. Today it’s the virtual home of hundreds of thousands of websites of doubtful integrity, although, contrary to Niue, the administrative earnings of the island’s government have benefited the infrastructure and services.

The form in which the geographic domains are managed on a higher level (ccTLD) is very different. The Internet Corporation for the Assignment of Names and Numbers (ICANN) has left it to the discretion of each country to do what it likes. Many countries keep them privatized, although in the hands of institutions or businesses created for that purpose, while in others it’s an entity attached to a state agency.

The ccTLDs (country code top-level domains, geographic domains of a higher level, which, for better understanding, is the name that the extensions receive that identify each country or geographic region: .cu for Cuba, .ru for Russia, .mx for Mexico, etc.) are even more curious.

Both forms of operating the ccTLDs described above have advantages and disadvantages. Deregulating the extensions shifts the balance toward the higher-profit businesses to the detriment of agencies, NGOs and institutions with social and cultural goals. This diminishes the influence of the governments, which can have a negative effect on the sovereignty of countries that are economically fragile, or on young or small countries.

State-regulated administration tends to protect social and cultural interests, and successful management can increase earnings, which has a positive impact on national life. It also happens that governmental norms for buying a ccTLD can be restrictive or discriminatory, protected by a deliberatively vague regulation to be applied at the discretion of the government.

In the Latin American environment, Argentina, the only country to offer its site for free and with millions of websites with the extension .ar, decided in 2014 to charge for them. In Chile and Nicaragua, administration is through the public universities. In Guatemala, it is also through a university, but a private one.

In Uruguay, regulation is by the State through the National Association of Telecommunications (ANTEL); in Venezuela by the National Commission on Telecommunications (Conatel); and in Cuba through the Enterprise of Information Technology and Advanced Telematic Services (CITMATEL).

Colombia reflects a debate similar to what is happening in other countries. A private enterprise manages its ccTLD, and 89 percent of the owners of the .co site are foreigners located outside the country which, far from violating the national identity, internationalizes Colombia and carries its trade name to the entire world. What underlies these debates is the idea that the market is imposing itself on cultural values, and national governments can do little in defense of their intangible patrimony.

But in short, who governs the Internet?

Any recently-arrived observer would say that the United States governs it. The institutions and most of the servers destined to organize what would otherwise be chaos are located in its territory. And the well-known ICANN, located in California, which assigns domain names (DNS) to the IP addresses, has a contract with the Government.

Businesses that have a lot of influence on the Internet, like Microsoft, Google or Amazon, are also in the United States. But this concept is changing: It is expected that in September, the process of transition for the custody of IANA, the authority for the assignment of domain names, will no longer be under the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, in order to give ICANN authority and independence.

Other parties that also participate in the Internet have interests opposed to this current asymmetrical influence. International organizations like the Commerce of Intellectual Property (OIC) or the International Union of Communications have been incorporating together with ICANN. Virtual space is modifying the notion of sovereignty, with the added danger for equality and diversity, so that the term “governance” is important in the designing of policies, where governments, civil society, businesses, academics and technical innovators merge.

In the same way in which the technical innovators have guaranteed open access to the Internet from any type of device, it is up to the governance to establish policies, even when they aren’t binding, to guarantee freedom of expression and information, full access to the Internet and limited control.

Translated by Regina Anavy