Interview of Dimas Castellanos by Ernesto Santana Zaldivar, published on April 26 and 29, 2013 in Cubanet.

Although still uttered timidly, recently you have begun to hear the word “negotiation” in some statements by the Cuban political opposition. Despite having diverse opinions about it, a negotiation is, in general, a process in which two or more parties try to find a mutually satisfactory solution to their problem, be it labor union, financial, military, commercial, political, etc.

The American expert on the subject, Herb Cohen, believes that “everything is negotiable” and defines negotiation as “a field of knowledge and action whose objective is to win the consent or the favor of the people from whom you want to get something.” He also says that the three main factors of a negotiation are power, information, and time.

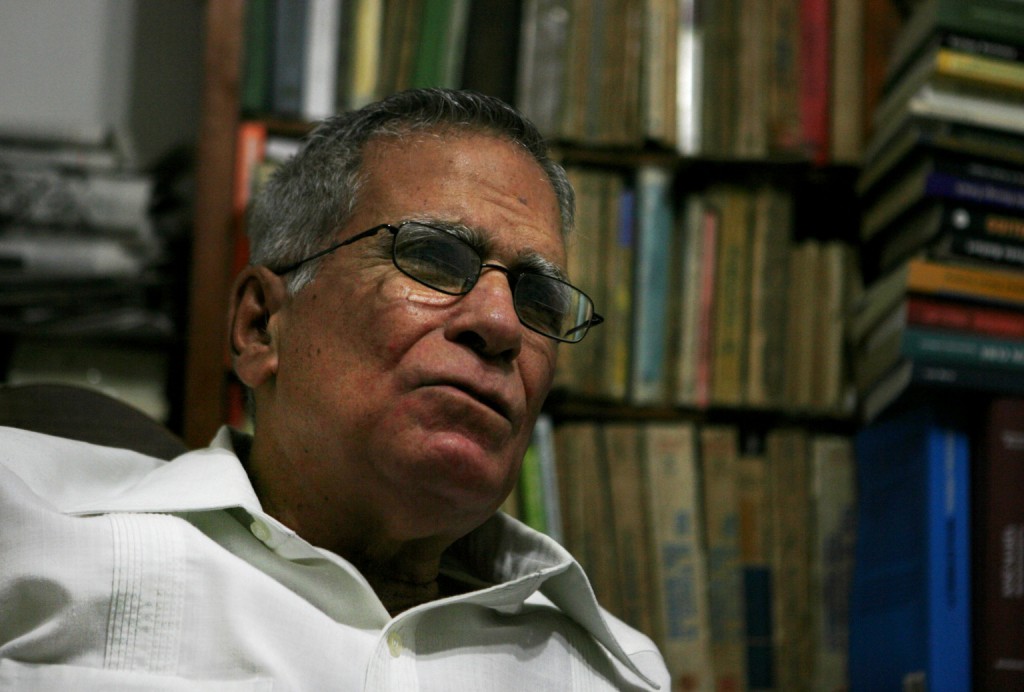

In order to approach, from a Cuban historical perspective, an issue so complex, but which has had such importance for determining fundamental political changes in many countries and eras, we talked with sociologist and historian Dimas Castellanos, also known for his independent journalism in the digital magazine Consensus, in Diario de Cuba, and in other media.

Cubanet: Do you think there is still no pressure in Cuba that requires the government to negotiate?

Dimas Castellanos: First, this is not the case of an armed movement that occupied a region of the country over which the government now has no control, as in Colombia. Another thing that may force a government to negotiate is that the opposition has such influence over a sector of the population that it can create difficulties for the authorities.

In Cuba there is great discontent, manifested for example in the elections: almost fifteen percent of the voters did not go to the polls or annulled their ballots. But they did so spontaneously, by an individual act of conscience. No one should believe that this was in response to some opposition party that has that kind of drawing power.

So the government has no reason, nor anyone with whom, to negotiate. And on the other hand the opposition is not strong enough to prevent the government from doing what it wants.

Cubanet: What, in your opinion, is the reason for this situation?

Dimas Castellanos: In Cuba, there were always forces that at some point could compel those in power to do certain things. These forces do not exist today. When the revolutionary government took power, the first thing it did was to dismantle the whole network of institutions that existed, mainly civic institutions. So all the citizen organizations, which had been here since the end of the Ten-Year War, disappeared.

Civil society, which erupted with force in the Republic, achieved admirable results, as the strike by apprentices and masons demonstrated in 1901 and 1902, which spread to other sectors.

By 1910, the government was forced to enact several legislative measures favorable to the working class, such as the eight-hour day for government workers, payment in cash and not in tokens and vouchers (as before), and paid holidays.

The labor movement accomplished all that because it had real strength and could, for example, paralyze sugar mills or transportation. Cubans now are not as poor as they were, but we do not have unions and other civil society organizations able to play that role.

Cubanet: So is it essential, first of all, to set up the network again?

Dimas Castellanos: It’s hard to understand that this is a long-term battle. And you have to pace yourself and take advantage of all the gaps and openings to help the civic formation of citizens. Many dissidents want change for Cuba, just as I do, who am also part of the opposition, but I try to be as realistic as possible.

The government is sometimes forced to take some step, more for external reasons than from pressure from within Cuba. After more than fifty years, it has the luxury of making reforms from the same position of power, and therefore can determine the pace and direction they take. They can make a change in one direction, then take back a little, then shift it forward again, and play with it, but there is no internal force able to avoid it.

The government will negotiate when there is a force that compels it to negotiate, and that force has to be formed over the long term.

Cubanet: Do you share the opinion of many Cuban historians that the Protest of Baraguá represents a milestone in our history as a method of negotiating without compromising dignity?

Dimas Castellanos: I regret that the Zanjón Compact has not received the historical recognition that it should have, and that only the Protest of Baraguá has been glorified, because it demobilized the rebel troops in exchange for Spain allowing in Cuba a regime very similar to that which existed in Spain itself or in Puerto Rico.

The laws of the metropolis governed here starting from the Zanjón Compact, and from it came freedoms of expression, association, and assembly, among other benefits.

Despite all the limitations that it kept, there Cuban civil society was born and the first political parties were created. The union movement grew, newspapers spread, there were organizations of all kinds – political, fraternal, labor – that began to take on an enormous burden within society.

The burden was such that you cannot understand the beginning of the war in 1895 without the work that civil society did in the whole colony. That was a time, in terms of freedoms, very superior to what currently exists.

Due to the shortness of time that this form of communication offers and at the same time, due to the interest and to the meaty responses from Dimas Castellanos, we have divided this interview in two parts which will be available to the readers in a coming edition.

Cubanet: In his first responses for this two-part interview, Dimas Castellanos explained the reasons why, in his view, the peaceful opposition movement in Cuba is not yet in a position to force the government to sit at a negotiating table. He also set out his criterion from examples of notable negotiated events that took place throughout our history. Just for this aspect we return to the theme.

Cubanet: How do you assess the role played by civil society in Cuba, as far as negotiation is concerned, in the Republican era, from its beginnings to 1958?

Dimas Castellanos: Negotiation played a role of obvious importance. The Constitution of 1901 is an example. The interventionist U.S. government allowed the formation of a Constituent Assembly and created the conditions for it, but, as it had the force of the occupation, it made sure that the Platt Amendment was incorporated to secure their power over the country.

More progressive Cuban forces strongly opposed the amendment and even traveled to the United States, but failed except for a few small changes. Although during the revolution those who signed the Platt Amendment were condemned, the truth is that there were only two options: either sign the addendum to the Constitution or the United States maintained its military control over the country.

And there were no longer mambises nor the Cuban Revolutionary Party, nor an economy; and a people, moreover, tired of wars. The best minds saw that they could lose everything and accepted the Amendment – although it was an insult, a humiliation – as a tactic, to then gradually remove it, as they did.

In 1934 the Platt Amendment was finally abrogated. And it was all through negotiation.

Cubanet: And in terms of the Constitution of 1940?

Dimas Castellanos: It was a master class in negotiating in which the participants ranged from communists to the extreme right. They arrived at a Constitution that provided balance, though perhaps, in my opinion, it was above the civic potential of the Cuban people. That is why afterward our military tradition manages to prevail.

There was not a strong civic tradition, but rather a dictatorship tradition, which is demonstrated in the governments from 1902 until the fall of Machado in 1933. Between that year and 1940 was very turbulent. After 1937 they managed to calm the situation a little and finally return to a democratic exercise that culminated with the Constitution of 1940.

Batista cleanly won the presidential election. Then Grau defeated him in 1944 with the Aunténticos, winning again in ’48 with Prío, and in 1952 he looked certain to defeat the Orthodox Party, which was nothing more than an offshoot of the Authentic Party, whose main argument was the prevailing political and administrative corruption.

Curiously, this corruption did not affect society, because, even though we were not very advanced in public spirit, the morality of the Cuban people was very high. After the 1952 coup, those who wanted to overthrow Batista were divided into two camps: on one side, the civic forces (the Law Society, the Medical Association, the Lions Club, Rotary Club, etc..), and on the other, those who opted for armed struggle.

Cubanet: We now know which was the winning side. What is not well understood, especially by the Cuban population, is what later happened with the negotiating capacity of our civil society.

Dimas Castellanos: The Revolution became the source of power, without any compromise with what existed before and swept it all away.

Actually, the Revolution had the support of only one part of the population (the fighting was carried out by a few thousand men in a population of six million), mainly peasant farmers, but the massive support occurred afterward and the Revolutionary government acted with skill. The result: it disarmed Cuban civil society, all the autonomous movements disappeared (of peasants, students, women, workers, etc.).

The unions were taken over in January 1959. Many who disagreed with that course thought that if Fidel Castro had taken power by force, he could also be overthrown by arms, but all violent resistance was defeated.

Cubanet: When can you say that Cuban civil society finally woke up, after the long slumber imposed by the Revolution?

Dimas Castellanos: In the late 80s and early 90s opposition organizations and political parties began to emerge, but very weakly, because of government repression first of all, and because many of the people continued to identify with the power, despite its failure, because the mindset does not change very quickly. Also because of the monopoly the government maintains over the media. It can say whatever it wants about the opposition and it is hard to deny internally. So it is isolated and marginalized.

From my point of view, the political parties that were created in the 90s are now worn out. That hurts a lot and no one likes to be told that, but I personally come from one of those parties, the Socialist Democratic, which has disappeared.

But a kind of proto civil society began to develop and there are movements with a very stable work, although they are not talked about much, such as Dagoberto Valdés, in Pinar del Rio, who has a method of advancing step by step and for years has insisted on the power of the small, with a theoretical basis for change, an accumulated political thought that should be used at some point.

But the problem of dictatorship continues, which we have always suffered with.

Cubanet: And what about the current conditions for strengthening the bargaining power of the opposition?

Dimas Castellanos: Now the government is exhausted and the model has proved unworkable.

With lack of freedoms there can be no development of anything, from the economy to sports. Everything is damaged, and the rulers do not want to engage in the suicide of promoting reforms that bring them to the end of the road, and result in their criminal prosecution.

To advance the economy and get out of the disaster, the government knows it has to connect back to the developed world, especially Western Europe and the United States, which conditions the relationship on respect for human rights, so it has begun to make small concessions.

In any event, the developed world believes that these reforms are still insufficient. That’s why the government is going to have to make more changes.

Cubanet: Do you think then that the new circumstances and the new waves of opponents are creating the conditions for a possible negotiator?

Dimas Castellanos: Whatever happens, the time for negotiation will come, though not in a situation like now exists.

The example is in the release of political prisoners, where there was no negotiation between the government and the opposition. Although many criticized the Church, I find that there was no other way and that civil society, which the Church is part of, was strengthened. Although the Church was able to meet some of its own demands, I don’t really think it was because it has common interests with the government, except for momentary tactical considerations. Strategically, the government and the Church are not going in the same direction.

There are now 400,000 self-employed workers who do not depend on the state. But what work has the opposition done among these workers? They do not think about human rights, but about their most basic needs. What they want is greater economic liberalization.

These 400,000 self-employed are a field in which we must work. We ought to create many more spaces, small schools about Cuban history, political courses, lessons about what a constitution is, about rights, because people will gradually come around.

The opposition has not given the importance that it should to the formation of civic society. You cannot fight for change if people do not even know where they have come from or where they are going.

The day that the opposition can say that the fifteen percent of the population that does not attend the elections is on its side, it will be a minority against the remaining eighty-five percent, but it will represent a great force because then it would be structured, and then it would be realistic to see the possibility of negotiations.

That’s what we have to work for. If we look at the history of Cuba, we see that we have always been changing, and yet we are now more backward in human rights than in 1878, because we backtracked on civil liberties. The Revolution of 1959 seemed like the greatest thing, but we fell into a trap and ended up worse than before. So our work has to be from the ground up and with patience.

Translated by Tomás A.

10 May 2013

HAVANA, Cuba , September 2013, www.cubanet.org.- Lech Walesa Institute in Warsaw hosted a workshop on nonviolent struggle (from September 4-14), participating in it were a group of human rights activists, political opponents and independent journalists living on the Island.

HAVANA, Cuba , September 2013, www.cubanet.org.- Lech Walesa Institute in Warsaw hosted a workshop on nonviolent struggle (from September 4-14), participating in it were a group of human rights activists, political opponents and independent journalists living on the Island.