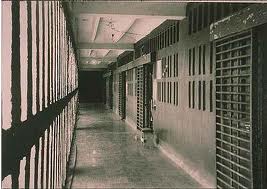

On the 18th of May, there were rumors floating around throughout the prison that the Division General and Chief of the National System of Penitentiaries, Rafael Calderin, was going to visit our jail. In Cuban prisons it is normal to pass on such news to informants and then they spread the word among the prisoner population. This is how they take note of the opinion of the jailed masses and keep certain prisoners from telling the visiting functionary about any anomalies.

On the 18th of May, there were rumors floating around throughout the prison that the Division General and Chief of the National System of Penitentiaries, Rafael Calderin, was going to visit our jail. In Cuban prisons it is normal to pass on such news to informants and then they spread the word among the prisoner population. This is how they take note of the opinion of the jailed masses and keep certain prisoners from telling the visiting functionary about any anomalies.

Lamentably, some prisoners express their desires to denounce to their supposed imprisoned companions, but as it turns out, some of these fellow prisoners inform the authorities of any intentions to protest in order to gain benefits. The guards control the situation with this very method, isolating those who may present any form of threat to their interests, prohibiting them from divulging any information about mistreatment and violations during any inspections.

When I heard such news, I supposed that the General would visit the section where we political prisoners from the group of the 75 were being kept. The sickest one of our group, Roberto de Miranda, lived in the penal infirmary. The rest of the group resided in the “Polish Cell”, while Blas Giraldo and I were kept in the third galley.

My intuition did not fail. After the lunch hour, a military committee (which included the chiefs of “Aguica”, the chief of the Matanza Prison System, and the National Penitentiary General) passed by my cell. I noticed that out of the corner of their eyes they looked towards my area, but they did not stop. They continued onto the cell of Blas Giraldo.

After some trivial questions about the state of his health, General Calderin asked for the book “More than a Carpenter” which my companion in struggle had in his hands at the time. After examining the pages of the book, the General said, “this material is now confiscated.”

“Can I know Why?”, questioned Blas Giraldo.

“Because it is a prohibited book,” the General responded.

“Since when is Johs McDowell prohibited in Cuba?”, my friend insisted.

General Calderin shot back, “Now, Blas Giraldo, don’t try to make me look like a fool.”

“Oh, right. Forgive my ignorance, I forgot that you are enemies of God,” Blas ironically responded.

A few minutes after, I felt the group of soldiers come closer to my cell door. Various common prisoners tried to talk to the General but he paid no attention to them. I suddenly heard the command to open my cell door.

“Good afternoon, Pablo Pacheco”, Calderin said with authority.

“Maybe it’s a good afternoon for you, and for all those who are accompanying you,” I answered back. “No one behind these bars can say that it is a good morning, afternoon, or night.”

I felt as if the majority of those who were in my cell were executing me with their stares, but I shot back with a similar stare.

Held aback for a few seconds, the General once again opened his mouth to say, “Pacheco, do you consider yourself a patriot?”

“At least I give the best of me to better serve my country,” I responded and added, “Do you consider yourself a patriot?”

“Of course,” he responded. “I’ve even gone to Africa to fight for Cuba”.

“For Fidel, you must mean,” came my impulsive answer.

“Let’s get out of here!”, he shouted. And all those with him followed the order. Before getting to the main door which leads out of “The Third” galley, he turned around a bit and told me, “Later, I’m going to send you a book written by Antonio Maceo.”

“I’ll read it with much attention,” I said with pride, “for I am an admirer of his legacy.”

Calderin’s behavior led me to believe that the whole point of his visit was to check our (the political prisoners) emotional states.

—

The next day after the visit, the chief of the Interior Order, Captain Emilio, came to my cell and told me to gather all my belongings, for I was going to be transferred. I asked him, “Where am I being taken?”

“I do not know,” he replied.

I knew that Emilio was lying, but I decided to accept his response. Various common prisoners that after the meetings with the General, their was a lingering risk that many of us would be taken to “The Polish” cell. We also were aware that since we were soon going to hold a fast for the 20th of May, the news had already reached the ears of the soldiers and they would try, with all their power, to isolate Blas Giraldo and I from one another.

Half an hour later, Emilio was opening the lock to “The Polish” cell, which I entered with my very scarce set of belongings. That is how the harshest period of my captivity began, and at the moment I was very far from imagining it. I had been held in “Aguica” for quite a while and I did not know when I would see my family again. And that was major concern. The rest was minor in comparison and I was determined to withstand it.

The Bible helped me during my most difficult moments. Now I know why whenever the guards would force us to only stick with three books in our cells, I never let go of it. It became my favorite book.

Translated by Raul Garcia, Jr.

9 February 2011

NOTE: Pablo Pacheco was one of the prisoners of Cuba’s Black Spring, and the initiator of the blog “Behind the Bars.” He now blogs from exile in Spain and his blog – Cuban Voices from Exile – is available in English translation here. To make sure readers find their way to his new blog, we will continue to post some of his articles here, particularly those relating his years in prison in Cuba.

On the 18th of May, there were rumors floating around throughout the prison that the Division General and Chief of the National System of Penitentiaries, Rafael Calderin, was going to visit our jail. In Cuban prisons it is normal to pass on such news to informants and then they spread the word among the prisoner population. This is how they take note of the opinion of the jailed masses and keep certain prisoners from telling the visiting functionary about any anomalies.

On the 18th of May, there were rumors floating around throughout the prison that the Division General and Chief of the National System of Penitentiaries, Rafael Calderin, was going to visit our jail. In Cuban prisons it is normal to pass on such news to informants and then they spread the word among the prisoner population. This is how they take note of the opinion of the jailed masses and keep certain prisoners from telling the visiting functionary about any anomalies.

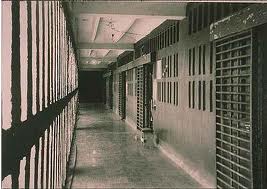

The American citizen Chris Walter Johnson, a prisoner in Combinado del Este since August 2009, went from uncertainty and depression to euphoria when on Wednesday, 2 February, two guards helped him get into his wheelchair in the ambulance which drove him to the Havana airport, from which he departed to Los Angeles, California, on the day on which the sentence of 18 years imprisonment was supposed to have been made final by a Provincial Tribunal of the capital.

The American citizen Chris Walter Johnson, a prisoner in Combinado del Este since August 2009, went from uncertainty and depression to euphoria when on Wednesday, 2 February, two guards helped him get into his wheelchair in the ambulance which drove him to the Havana airport, from which he departed to Los Angeles, California, on the day on which the sentence of 18 years imprisonment was supposed to have been made final by a Provincial Tribunal of the capital.