When in October 1998, Luis Cino, 53, came to the small house belonging to the reporter Mercedes Moreno, an independent journalist who for years worked on Cuban television, he thought twice before knocking on her door.

Small, skinny and shy, Cino thought to try his luck as a journalist without a mandate at the agency that Moreno directed. After chatting with her less than ten minutes, Mercedes studied him in silence and said, “You look like a junkie or a freak, but write something, then we’ll see.”

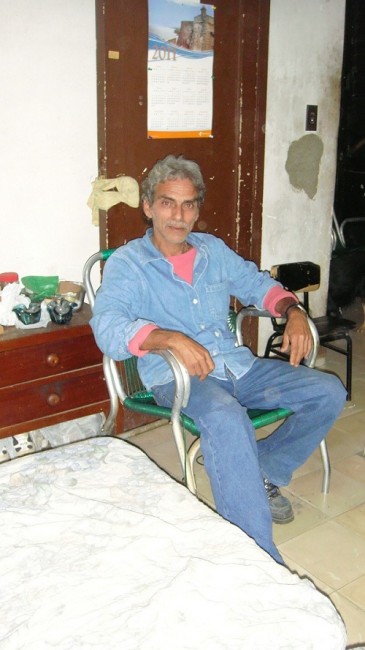

Thirteen years later, he doesn’t remember the subject of his first article. He says this sitting in a room in the neighborhood of Lawton, the seat of Primavera de Cuba (Spring in Cuba), a site that is updated weekly and has a quarterly newsletter, produced entirely from the island, where Cino is the editor and star reporter.

“I was a piece of shit with affected pretensions. I had taken two or three courses in literary workshops, and I read about 50 books a month. I reread the books of Vargas Llosa and García Márquez so much, the pages shredded in my hands. All I know is that I have an immense debt to Mercedes Moreno for giving me the opportunity to try my hand at journalism. It’s not easy to accept a guy who stammers and has no backing, who wants to be a correspondent in an illegal agency,” says Cino smiling.

Mercedes knew how to recognize talent. After crossing out with red ink half the sheet and making some quick observations, she knew that the “guy who looks like a junkie” was a potential journalist.

And she was right. His style became more refined, and, by 2000, he was one of the best Cuban independent journalists. Raúl Rivero, a giant of poetry and prose, and a talent scout, after reading a text by Cino, knew he was facing a writer of caliber.

Rivero recruited him for the team, which together with Ricardo González Alfonso in 2002, published the first issue of a magazine produced entirely on the island by independent reporters.

His impeccable command of language and lively style, agile and photographic, gives the illusion of watching a newscast on TV. It’s so graphic, that if you put your imagination to work you can see what he’s relating.

Luis Cino doesn’t believe that he’s a classy reporter. “At best I’m a man who writes without spelling errors and who talks about the real, daily life of my country,” he says, sitting in front of a computer, where he edits a half-dozen notes.

But in this February of 2011, without doubt, Luis Cino is the best freelance journalist who currently exists in Cuba. Dissidents, alternative journalists and bloggers, who rarely agree on anything, agree that not only is he the best writer, he’s also a great person.

His small attempt to be in the limelight and his stubborn vocation of working anonymously on a draft suggest that his talent is understated. He doesn’t think so. “In journalism, what matters is the news. Whoever writes the draft is a driving force. If you get the reader to fully read your story, you’ve accomplished something. If it moves and creates a state of mind, then you’ve succeeded. But a reporter is not a Hollywood star,” he says, while smoking the third cigarette of the afternoon.

He’s allergic to fame. He creates blindly at work every day. He says that the worst enemy of a reporter is flirting with politicians. “Politicians always try to use you. If you want to do the most objective journalism possible, you have to keep a distance from them.”

In these thirteen years, Luis Cino has suffered arrests and harassment by State Security. When the March 18, 2003 raids began on the 75 dissidents and independent journalists, Luis was working at the home of Ricardo González, one of the 27 reporters sent to jail, and who, thanks to the efforts of former Foreign Minister Moratinos, now lives in Spain.

“It was around 4:00 in the afternoon when the officers arrived in droves from State Security. They did search that lasted eight hours. They detained me for one and a half days in a stinking cell with no ventilation in the 6th police unit of the municipality of Playa. I was lucky, I was not indicted,” he recalls.

Although fear gripped him, as it did everyone, in the following days he continued to report on the arrests and the situation in Cuba. Despite much good writing, Luis Cino has been forced to take on a number of parallel jobs to earn money to support his three children.

He has been a postman, demolished old buildings, been a brick-layer assistant and a watchman at a dairy, where at dawn, by candlelight, he wrote his formidable chronicles and stories.

He usually is left with a few pesos in his wallet, after a breakfast of black coffee, at 6 in the morning. He takes a crowded bus that brings him to the house where the Primavera de Cuba office is located.

He has never thought of leaving his homeland. His dream is simple. He will continue writing chronicles from Havana, and in that future that is upon us, when journalism in Cuba is a profession without ideologies, he will continue editing a cultural column in a city publication. He asks no more.

Translated by Regina Anavy

February 2 2011