Vicente Botín, Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE), The Hilton Miami Downtown Hotel, 29 July 2016.

A female cat fell in love with a handsome young man and prayed to the goddess Aphrodite to turn her into a woman. The goddess, pitying the cat’s yearning, transformed her into a beautiful maiden, and the young man, captivated by her beauty, married her. But, on the wedding night, Aphrodite wanted to know if the cat, now a woman, had changed inside as well, and so she let loose a mouse in the bedroom. The cat, forgetting her status as a woman, rose from the bed and chased the mouse so as to devour it. At that point, the goddess, grown angry, returned her to her previous condition, turning the woman back into a cat.

With this fable, the Greek philosopher Aesop means to tell us that, “The change in status of a person does not cause her to change her instincts.” Which the wise collection of popular sayings might translate as, “You can dress up a monkey in silk, but she is still a monkey.”

“Why this eagerness to dress the monkey in silk?” I asked myself, when I saw, incredulous, the Chanel parade in Havana. The Adidas tracksuit which Fidel Castro has been sporting for years was outshone by fashion czar Karl Lagerfeld’s diamond-studded jacket and Brazilian supermodel Gisele Bündchen’s beret (albeit without the star that adorned Che Guevara’s cap in that famous photograph by Alberto Korda). continue reading

Could it be that vileness can be disguised by glamour? Is is possible to wrap in gift paper, as though it were a box of chocolates, the Penal Code in force in Cuba, which brutally punishes all forms of dissidence?

Can repression and the lack of freedoms be combined with haute couture? Is the march by the Ladies in White along Fifth Avenue compatible with the pageant of Chanel models along the Paseo del Prado?

Giusepe Tomassi de Lampedusa puts in the mouth of Tancredi, one of the characters in his novel, “The Leopard,” this utterance directed to his uncle Fabrizio, Prince Salina: “Everything must change if everything is to stay as it is.”

In political science, “leopard-like” or “Lampedusian” are descriptors for the politician who initiates a revolutionary transformation but which, in practice, alters the structures of power only superficially, intentionally keeping the essential elements of those structures.

Raúl Castro is a lot like the Lampedusian Tancredi, because he seems to want to change everything, but his intention is for everything to stay as it is.

When I arrived in Havana in early 2005 as a correspondent for Televisión Española, everything was much clearer, or, to be more exact, seemed less confused. There were no fireworks. Any glamour, for want of a better term, was provided by Fidel Castro, with his eternal olive-green uniform, and the parades were not directed by Karl Lagerfeld, but rather by the dictator himself, on the Malecón, in front of the then-US Interests Section, now the US Embassy.

Of course, then these demonstrations were called “Marches of the Embattled People.” The other marches, those of the Ladies in White, were repressed without pity, and concerts, such as those by the group “Porno para Ricardo,” were nothing like those by the Rolling Stones: they would end with their leader, Gorki Águila, in jail. There is where the dissidents could be found, the ones from the Black Spring of 2003, and other, newer ones, who were continually being thrown into the prisons.

At that time, Havana was falling to pieces. There were power blackouts, and the ration book was entirely insufficient to meet the basic needs of the population. The US was the imperialist ogre, the culprit of all the evils afflicting the country, and the spies, “The Five,” were heroes. There were no shades. Everything was black or white.

Now I ask myself, “Has all that changed? Is it all part of the past?”

When he was named the successor, and with his brother still physically present, Raúl Castro started his own trajectory. He proceeded like a good bureaucrat, without rhetoric, step by step, convinced that, in order to survive, the Revolution needed a facelift. So he pulled out of his hat a jar of makeup, a tube of lipstick and a comb, and with an oriental patience (it is not for nothing that they call him “the Chinaman”*), he began to embellish the corpse of the Revolution until he made unrecognizable… unrecognizable for the gullible who let themselves be fooled by Photoshop.

Cuba is in fashion, and the mirage of the reforms serves as a screen to cover the reality that Cubans live, or rather, suffer. Could it be that they are invisible who inhabit the Island? Do they no longer have to steal or deceive in order to survive? Do they no longer have to “resolve” their problems?

There has been too much speculation over the nature of and the time it will take to implement these reforms that have been announced so many times, like the Byzantines used to speculate, in the 15th Century, about the sex of angels, while the Ottomans were besieging Constantinople.

Could it be that the Turks are at the gates of Havana?

The Turks, probably not, but the Cubans yes, who for more than half a century have lived besieged within a fortress, commanded by an apprentice and witch doctor, who is performing a balancing act to contain the demands of a people beleaguered by penury and the lack of freedoms.

The foreign correspondents who work in Cuba confront the dilemma of rummaging through the trash or going with the flow. During the four years that I spent on the Island, I suffered all types of pressures to force me to sweeten my reports. The censors were not concerned with political criticisms, after all, the Cuban government enjoys no few sympathies throughout the world. What bothered them was the pure and simple description of the difficult living conditions of the Cuban people. The shameful condition of the hospitals, the precariousness of the housing, the cut-offs of water and power, the scarcity and bad quality of the food, the lack of transportation, and let us not mention the prostitution, as a express route to access consumer goods.

All those topics were taboo. They could not be mentioned, under threat of expulsion. The paradox is that currently, all of those problems continue, they have not disappeared, but they appear to no longer be a problem for anybody. Simply put, they are not spoken of. They are swept under the rug.

The first “reformist” measures announced by Raúl Castro provoked an effect similar to hypnosis. Like an expert prestidigitator, he exchanged the bread and circuses of the Romans for self-employment licenses, cell phones, cars, houses and microwave ovens, despite their high cost in Cuban Convertible pesos (CUC).

But Cubans, after so many “absurd prohibitions,” celebrated them joyously and, beyond that, the announcement of new promises–among them, the suppression of the double currency, the revaluation of the Cuban peso, and the end of the ration book which, in Cuba, ironically enough, is called the “provision” book.

But it is well known that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Eight years later, those good intentions have yet to be realized, especially the suppression of the double currency, which not only has not been resolved but has become even more complex, with the application of different exchange rates.

For Raúl Castro this is the cause of “an important distortion, which will be resolved as soon as possible.” It will not be put off until the Twelfth of Never, the dictator has said, but at this rate, it will be resolved when hell freezes over.

The dual monetary system — the Cuban peso (CUP) and the Cuban Convertible peso (CUC) — is cause for no few arguments among brainy analysts who do not tire of debating over the consequences of solving that problem through a type of shock therapy or, conversely, doing it in phases.

While the dispute rages on over whether they are greyhounds or wolfhounds, until the Island’s government solves the enigma, Cubans will suffer the consequences of that distortion that suffocates them, because their salaries are paid in Cuban pesos, but they must use CUC to buy practically everything they need at a 25% markup.

The minimum salary on the Island is 225 Cuban pesos, and the median monthly salary is 625, which come out, respectively, to about 9 and 25 CUC or roughly the same in US dollars. What can one do with that amount of money? What would you be able to do with an income of $25 per month?

The cost of the products in the “basic basket,” subsidized by the government is, approximately, 10 Cuban pesos per month. It it is simply impossible, however, that one person, especially a retiree, with no other resources but his pension, can subsist all that time, with just a few pounds of rice and beans, the basic food of Cubans, to which are added a few ounces of pasta, coffee and salt.

The ration book also provides for five eggs per person per month, and a few more more for 10 pesos: a bit of oil, another bit of ground soy meat, a bar of soap… come on, it’s as if one had just come out of a war zone.

Aside from the ration book, one can purchase (also with Cuban pesos) certain unregulated products, but the true foodstuffs, beef and fish, primarily, can only be bought with CUCs.

And although the government recently lowered the price of some basic products, these continue being very high. For example, one kilo of frozen chicken costs 2.35 CUCs, and a half kilo of powdered milk, 2.65. Just these two products account for 20 percent of the median monthly salary.

In the world in which we live, it seems absurd to speak in these terms. Has any one of you ever told a guest that you cannot make her an omelet because you have already consumed your five monthly eggs?

Cubans do not live in our world. To not understand that is to turn on its head the myth of Plato’s cave and to accept that the people inhabiting Cuba, chained and in the shadows, live in the real world and we, on the other hand, in an apparent reality.

Allow me to ask you some questions. Has any one of you recently visited a house in Centro Habana? A great number of them are propped up to prevent collapse and, even so, this occurs almost daily, with a high number of fatalities.

Did you know that in the hospitals, the sick must bring their own sheets, their food and even a bottle of bleach for sanitation, due to the abysmal hygienic conditions, and that infections in the operating rooms result in a high rate of deaths?

I invite you to visit, for example, La Balear hospital in San Miguel del Padrón. It is not in Haiti, but rather in Havana, the capital of the country that publicizes its health system as one of its greatest accomplishments.

Are you aware that diabetes patients only receive, on a monthly basis, between two and five sterile, single-use syringes of insulin, and that the rest that they need they must buy them on the black market or, as recommended, boil the used ones?

Do you know that hopelessness is causing a stampede toward the United States, and the exodus to that country has quintupled in the last five years?

Do you know the number of boat people who escape to the United States for lack of a travel permit, despite the much ballyhooed migratory reform, and perish in the Florida Straits?

All of this occurs, continues to occur, while the eyes of the world are turned to the reforms that have been implemented in recent years, although it remains to be seen to what extent they will be affected by what Raúl Castro has euphemistically called “tensions” and “adverse circumstances” provoked by, among other factors, the crisis in Venezuela, which has substantially reduced the shipments of oil to the Island.

The reforms yet to come are discussed, exhaustively, in forums such as this, but there are always more questions than answers because only the government of the Island holds they key to what it will do and when.

And the Cubans? What role do they play in all this? Are they and their circumstances also an object of study?

If you allow me I will parody Shakespeare in “The Merchant of Venice” to say, “Does a Cuban not have eyes? Does a Cuban not have hands, organs, proportions, senses, affections, passions? If you prick us do we not bleed? If you poison us do we not die?”

Cubans do not have a dog in this fight. They attend, mute, to the government’s hot air and do what they have always done under the dictatorship: survive.

And surviving in the towns of the interior is much more difficult than in the capital. The living conditions of millions of Cubans are pitiful. The metaphor of Italian writer Carlo Levi would have to be employed, and say that Christ was detained in Havana, because further out from the capital, Cubans live outside of history, crushed by poverty.

But the government, insensitive to the privations of Cubans, walks and walks toward the precipice.

Among the litany of lamentations over the failure to fulfill the economic plans, during the recent sessions of the National Assembly of People’s Power, voices of alarm were heard before the possibility that the situation will deteriorate even further and produce a social outburst, with a repeat of street protests such as those of the Maleconazo of 1994. As a precaution against such incidents, the government is sharpening its knives.

But the spotlights, at present, are shining on the enormous cinematic stage which Cuba has become for the world, and especially on the proposals of the VII Congress of the Communist Party, which took place this past April.

Essentially, what was discussed there was what the government understands as the “conceptualization of the socioeconomic model,” which in reality is nothing more than the continuation of the so-called “Alignments of the Social and Economic Policy of the Party and the Revolution,” presented during the previous Congress and which, like all good resolutions have been left half-baked.

The conceptualization is now in its eighth version and only 21 percent of the 313 Guidelines have been implemented; the rest, that is, the 79 percent, is “in-process.” At this rate, it will take decades to put the well-worn guidelines into practice.

Similarly, the Mariel Special Development Zone has dropped anchor: of the 400 investment projects that were predicted, only 11 have been accepted; within a century, perhaps the rest will have been approved.

The government continues to beat around the bush and appears not to fear that it is past its prime. Meanwhile, it maintains control over the means of production, what it calls the “predominance of the property of all the people,” although in the last five years the state sector diminished, from 81 to 71 percent, while the private and cooperative sector expanded.

The government of Raúl Castro is confident in the new Foreign Investment Law’s capacity to attract capital, authorizing outside investment in all sectors of the economy, except in health, education, armed forces and communication media.

But there is much mistrust on the part of the investors regarding the guarantees they will receive on acquired properties and the transfer of utilities in foreign currency. The law is very ambiguous in this regard, as it establishes the freedom of investors to repatriate their profits, so long as doing so does not constitute, and I quote, “a danger to the sovereignty of Cuba.”

Another negative aspect is that joint ventures or enterprises funded by foreign capital will continue to not have the power to contract their employees directly; they will have to do it through government entities charged with negotiating salaries and other working conditions.

This practice was in place under the previous law and implies an infringement of the rights of workers who are without free unions to represent them.

More than a few discriminations are suffered by Cubans, without the new laws, the laws of the much -vaunted changes, protecting them.

The current Foreign Investment Law allows Cubans who reside overseas to invest in Cuba, but not those who live on the Island. They are prohibited from investing in their own country.

The executive director of Cuba Archive, María Werlau, recently made a presentation to the US Congress denouncing the repugnant business of human trafficking carried out by the Island’s government, and which has become its major source of revenue: something more than $8-billion, compared to the $3-billion produced by tourism.

According to official data (I quote María Werlau), around 65,000 Cubans work in 91 countries, with 75 percent (approximately 50,000) in the health sector. Their services are sold abroad, and the greater part of their salaries is confiscated by the Cuban government.

The violations of universal labor rights, which such a practice implies, infringes international accords signed by Cuba and by the majority of the countries where these exported workers are laboring, including conventions and protocols against the trafficking in persons, and of the ILO, the International Labour Organization.

The wage vampirism practiced by the Cuban government attains its most repulsive aspect in the trafficking of blood. The massive drives to obtain donations made voluntarily and altruistically, even using coercive methods, cover up a lucrative business, which some sources estimate brings in some $30-million per year. The government sells the blood of Cubans overseas, with no concern for the shortage of reserves in the Island’s hospitals.

The doses of capitalism which Raul Castro is introducing in Cuba ma non troppo, as the Italians might translate Castro’s slogan “without haste but without pause,” do not alter in the least the stone tablets of the current Constitution that is in force, which establishes an “irrevocable” one-party regime, of “Marxist-Leninist ideology and based on the thought of Martí,” as an “organized vanguard of the Cuban nation, primary leading force of society and of the State.” And to overlook this means to not understand what country we are talking about.

In Cuba, there are no political prisoners, according to Raúl Castro. But in fact, there are, and many. It is enough to consult the statistics put out monthly by human rights defense organizations.

Are you familiar with the Article 72 of the Penal Code? If you have read “1984,” the shocking book by George Orwell, you will recall that the “thought police” would go after “thoughtcrime,” crimes of the mind.

So, then, Article 72 of Law Number 62/87 of the Cuba of the supposed changes, is a carbon copy of the Orwellian laws.

That article says the following: “The special proclivity in which a person is found to commit crimes, demonstrated by the conduct he observes, in manifest contradiction to the norms of sociality morality, is considered a state of dangerousness.”*

In other words, the police can detain anyone suspected of hiding subversive ideas in the deepest part of of their consciousness.

The appointment of Miguel Díaz Canel, 56 years old, an “apparatchik” of the Communist Party, as first vice-president of the Council of State, and the announcement, made by Raúl Castro himself, that he would cede power in February 2018, could mean that the regime was heading towards renewal, at least generationally. But, once again, it was apparent that all was purely cosmetic.

If, in fact, Raúl Castro reiterated, during the VII Congress of the Communist Party, his intention to resign from his position as President of the Councils of State and of Ministries, he was reelected “Bulgarian style”** with 100 percent of the vote, as First Secretary of the Party for the next five years, that is through the year 2021, at which time he will or should reach, if God does not intervene, the age of 90 years.

At that time, Raúl Castro will turn over the secretariat of the Party and also, in his words, “the flags of the Revolution and of Socialism, without the least trace of sadness or pessimism, with the pride of duty accomplished.”

As Don Quixote says, “for empty words, the noise of bells.”

And what did the President of the United States try to do by going to that Island situated beyond all comprehension? Like Hank Morgan, the hero of Mark Twain’s celebrated novel, “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court,” Barack Obama was transported to the land of never again, convinced that normal diplomatic relations and a surge in commerce will give way, in the end, to greater liberty for Cubans.

Hank Morgan was saved from death by fire by knowing when a solar eclipse would occur, but Barack Obama, lame duck that he is, was slowly roasted over a barbeque.

For the exegetes of the Revolution, Obama did not go to Cuba, as he said, with the purpose of “burying the last remnant of the Cold War on the American continent,” but rather with more nefarious intentions. The United States, according to Raúl Castro, has changed its former hostile strategy for “a perverse strategy of political-ideological subversion that threatens the very essences of the Revolution.”

As the song says:

Not with you and not without you

are my sorrows eased

with you because you slay me

without you because I die.

The United States has taken giant steps in the normalization of its relations with Cuba, and the Island’s government is taking good advantage of this. But it has not changed its rhetoric, nor has it advanced one millimeter on the path that leads to democracy.

The rapprochement between the two countries has provoked an enormous controversy between supporters and detractors, while Raúl Castro and his minions observe the bullfight, with satisfaction, from the sidelines.

For The Washington Post, the policy of the Obama Administration toward the Cuban government has stymied the efforts of those who fight for democracy on the Island: the activists who have spent their lives struggling against the regime at enormous personal cost.

It is they, and the Cuban people, who should lay the foundations of a new nation with democracy and liberty, and not those who, illegitimately, have usurped that right and want to continue doing so through deceit.

The Cuban Revolution is a corpse, but that corpse has not yet been buried, and its stench will take time in going away. Meanwhile, Cubans continue to live inside a cage with heavy bars, which the government is now sugar-coating, like sugar-coating a pill to hide its bitterness.

As in Oscar Wilde’s gothic novel, “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” Raúl Castro shows a benevolent face, but his smile is the reverse of a mocking grimace. His tactic is tall tales; his strategy, maintaining his position in power.

Allow me to end my contribution by reading a brief poem of León Felipe, a Spanish writer exiled in Mexico after the Spanish civil war. It is entitled, “I Know All the Tales,” and I believe it reflects very well the great deceit of the Cuban government’s reforms.

It says:

I do not know much, it is true.

I only tell what I have seen.

And I have seen:

that man’s cradle is rocked by tales…

That man’s cries of anguish

are drowned out by tales…

That man’s weeping is tamped down with tales…

That the bones of man are buried with tales…

And that the fear of man…

has invented all the tales.

I do not know much, it is true.

But I have been lulled to sleep with all the tales….

I know all the tales.

Thank you very much.

Translator’s Notes:

*In fact, Cubans call Raul Castro not “El Chino,” as in the original text here, but “La China” — The Chinese Woman — as a slur on his parentage and his sexuality.

**”Pre-criminal dangerousness” is a crime in Cuba’s Penal Code and carries a sentence of 1-4 years in prison.

*** An expression that alludes to the former Soviet bloc, and decisions made unanimously–more out of fear or coercion than by conviction–during Communist Party meetings.

Translated by: Alicia Barraqué Ellison

Cubanet, Luis Cino Alvarez, Havana, 9 February 2017 — Try as I might—to avoid being a bore and accused of holding a grudge against the boy—I cannot leave Harold Cárdenas, the ineffable blogger at La Joven Cuba, in peace, I just can’t. And the fault is his own, because the narrative he makes out of his adventures defending his beloved Castro regime, and his loyal candor, strikes one as a kind of masochism worse than that of Anastasia Steele, the yielding girl in Fifty Shades of Grey.

Cubanet, Luis Cino Alvarez, Havana, 9 February 2017 — Try as I might—to avoid being a bore and accused of holding a grudge against the boy—I cannot leave Harold Cárdenas, the ineffable blogger at La Joven Cuba, in peace, I just can’t. And the fault is his own, because the narrative he makes out of his adventures defending his beloved Castro regime, and his loyal candor, strikes one as a kind of masochism worse than that of Anastasia Steele, the yielding girl in Fifty Shades of Grey.

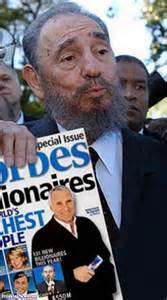

Hablemos Press, 26 November 2016 — The dictator Fidel Castro has died in Havana this 25 November. He was among the military men who ruled the Island with an iron fist for 49 years, amassing a great fortune–despite being a critic of capitalism.

Hablemos Press, 26 November 2016 — The dictator Fidel Castro has died in Havana this 25 November. He was among the military men who ruled the Island with an iron fist for 49 years, amassing a great fortune–despite being a critic of capitalism.

Cubanet, Luis Cino Alvarez, 30 September 2016 — The

Cubanet, Luis Cino Alvarez, 30 September 2016 — The