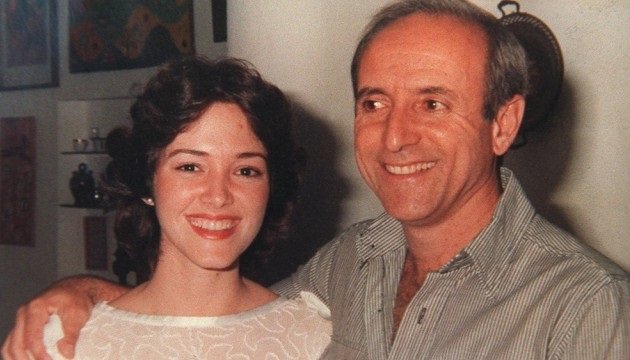

Juan Juan Almeida, 16 December 2016 — Twenty-seven years after Cause Number 1, the judicial proceedings that resulted in the deaths by firing squad and arrests of several high officials of the Cuban army and secret services, Ileana de la Guardia–daughter of the then-colonel of State Security of the Havana regime–believes that the decision to execute her father was made by the Cuban dictator to teach a lesson.

According to De La Guardia, who lives under asylum in France, Castro did not accept the critiques that her father and others, such as the general Arnaldo Ochoa–also executed–made regarding the need for changes in the country. She affirmed that the deaths of her father, Ochoa, and two other officials served as a way to cast the blame on them for the charge by United States Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) that Cuba was involved in international drug trafficking.

Until the time of your father’s trial, who was Ileana de la Guardia, how did you learn of the trial, how did you experience it?

At that time I was living in Cuba, had finished my university studies, and was a psychologist. I learned of the seizures of my father and my uncle, Patricio de la Guardia, on the same day. We did not know where they were nor what the charges were. Eventually, we learned that they were being held at Villa Marista [Central Offices of Cuban State Security], and we went there. Upon arriving we were told that they were being detained, that they were not arrested, that we had to leave, and that nobody could tell us what the charges were. This is how justice works in Cuba–“justice” in quotation marks, that is, because it is not justice.

A week went by, and I was given the authorization to see my father. I asked him if he knew what he was being accused of and he told me no. I also asked him if he would be tried, and he said he didn’t know. That same day in the evening, when I arrived at my grandparents’ house, I learned from a phone call that I was required to appear in the auditorium of the Armed Forces (FAR) the next day because that was where the hearing would take place.

Imagine receiving this news without them having the right to have their lawyers present. The lawyers who were there were “public” defenders. The one assigned to my father told me that he was ashamed to represent him. The one for Patricio told us that he had not had time to read the file and did not really know how to defend “that gentleman.”

That was when we knew that they were all lawyers with the Ministry of the Interior (MININT). Before starting the proceedings, before trying them, Granma newspaper ran headlines announcing the death penalty. The front page said, “we will cleanse with blood this offense to the fatherland.” It was clear that the decision to execute them had already been made.

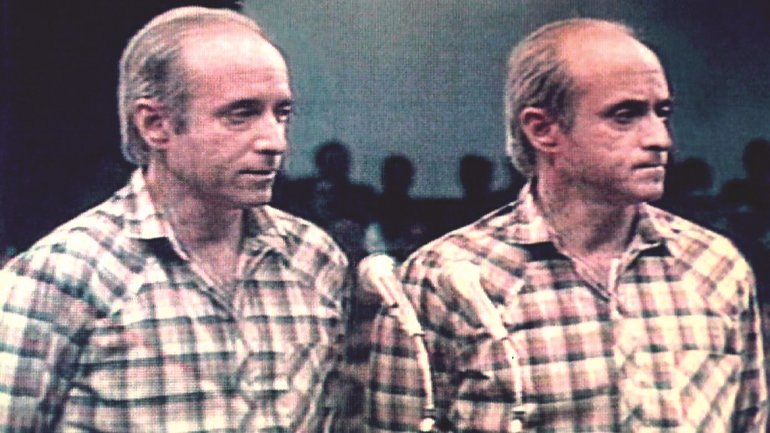

The trial was a kind of circus in which all were accused or accused themselves. Later we learned that they had been blackmailed, that they had to incriminate themselves to escape the death penalty–and to protect their families–there was a lot of blackmail with regard to the families. Thus the trial went until the end.

Our family wanted to appeal, but we were denied. Later, the Council of State, fully and unanimously, came down in favor of execution. They were executed exactly one month after being arrested: General Arnaldo Ochoa; Martínez, the assistant; my father, Colonel Antonio de la Guardia; and his assistant, Amado Padrón.

The memory of that trial brings back images of confusion and much division within the high military command. How do you remember it, and what were the repercussions for you, your family?

The consequence for our family was being watched all the time. There were always cars parked near where we lived, and when we went out, these cars would follow us with officials inside them who would watch us. There were also cameras filming us from the houses across the street from ours.

Your father, as well as Patricio (the brother of your father, Antonio de la Guardia), and General Arnaldo Ochoa were well-known and admired men. Throughout that trial, what happened with their friends?

I could not say that all the friends stopped seeing us; I believe some people were afraid, others were not. I maintained relationships with many people who continued coming to see us. I know that many people were let go from the MININT, many officials, a high percentage. That ministry was taken over by Abelardo Colomé Ibarra, who up until that moment was in the FAR. There was a takeover of the Interior Ministry by military officials.

What information do you have about the real reason that your father and the other defendants in Cause Number 1 of 1989 were executed?

From the beginning, I knew immediately that the charges against Ochoa and Patricio, who were in Africa, were trumped up. All of them were charged with drug trafficking, which made no sense. If they were working in Africa throughout so many years, directing the Cuban troops in Africa, how were they going to be accused of something that they couldn’t control? If drug trafficking was going on, and the ships were docking in Cuba, it was happening while these men were in Africa.

Later we realized that Raúl Castro, in a speech to the armed forces that was broadcast on television, had said, “those officials who are criticizing, let them go to Eastern Europe,” and then, “down with Ochoa.”

Then, connecting the dots, we realized that Ochoa and the group of officials around him criticized Fidel Castro and the regime a great deal because of the need for changes. This reached the ears of Fidel and Raúl because Ochoa had made sure to make it public, within the army and in family gatherings–besides telling them directly.

This is the fundamental reason why Fidel decided to eliminate these officials: because of the political aspect.

Meanwhile, the DEA was accusing Cuba of involvement in drug trafficking to the United States, and Castro found the perfect excuse to eliminate these military men while at the same time eliminate the DEA’s accusation of the Cuban government.

Prior to these events, what would you hear your father say about Fidel Castro?

As of 1986 or 87, there were very critical articles starting to appear in the press in Cuba, in the [Spanish-language Soviet] magazines Sputnik and Novedades de Moscú, which spoke of glasnost and about how Gorbachev was trying to make rapid changes.

People read these publications and these topics were discussed a great deal in my father’s house, we would speak of it on the patio. They thought the place might be bugged but they didn’t care.

The fact of being at a high level of command and knowing that the Soviets were already changing the system made them think that Fidel Castro would accept this. They thought that he couldn’t be so crazy as to oppose the changes. “He has to realize that this doesn’t work anymore, people must be given freedoms to express themselves, to travel, to have human rights”–they talked about all of this.

When I left Cuba–first to Mexico and later to Spain–it was very difficult to talk about this because we were still undocumented, we had no residency anywhere, no political asylum. It was in France, where we received support, including political asylum, where I decided to speak publicly. Articles started to come out, journalists started to investigate, and other facts emerged. We learned that there are officials in Russia who say that Ochoa met in private with Gorbachev in Cuba. Ochoa spoke Russian, there was nobody else present, Gorbachev wanted to speak only with Ochoa. Fidel could not stand this.

Ochoa never kept quiet about anything. One day, right in front of me at Patricio’s house, he said, “This has to change, it cannot go on this way, that man is insane, what are we going to do with the crazy man.”

In Cuba, it was always said that the writer Gabriel García Márquez, winner of the Nobel Prize in literature and personal friend of Fidel Castro, tried to intercede so that they would not execute your father and Arnaldo Ochoa. Is this true?

What I know for sure, because my husband Jorge Masetti and I went to see him, is that we took García Márquez a letter from my grandmother, asking him to intervene so that these officials, including my father, would not be put to death.

He told us, “I will do everything possible, I believe that this is not a good idea, and I have tried to get across to Fidel Castro that it is not a good idea for him personally.” But I never had proof that he did this.

After the execution, did you ever see García Márquez again? Did he tell you anything about this matter?

No, never again. I was now the daughter of a traitor. García Márquez was a powerful man, friend to powerful men. After being executed, my father was no longer a powerful man, he was a victim.

Did you have the chance to speak with your father after the sentence and before the execution?

Yes, before the trial, then during the trial I had a visit, during which he gave me to understand that they asked him to take responsibility and then they would not execute him, but that there was blackmail regarding the family and also with his life, and if he did not say that [incriminate himself], they would execute him.

And they did execute him. During the visit prior to the execution, which was very personal, he said, “things are going to get bad, but very bad, in this country.” Later came the “Special Period [grave economic crisis].” He knew what was awaiting Cuba.

Have you had any further news of your uncle Patricio, where he’s living? Does the government provide him with any retirement pension?

I cannot speak about this very much because it is a bit sensitive. What I can say is that he paints, because they [Antonio and Patricio de la Guardia] were painters before being military men, and they studied at an art school in the United States. He paints very well. He lives in the family home, it is not a house given to him by the Cuban state. Our family had properties before 1959. I don’t speak much about him these days, because if I say where he is or if I say too much, they will throw him in jail again.

Do you have contact with the family of General Ochoa or any of the other executed officers?

No, none.

In 2006, because of illness, Fidel Castro gave over the command of the country to his brother, Raúl. The day after this announcement, I entered the cafeteria of the Karl Marx Theater in Havana, ran into one of the daughters of General Ochoa, and she told me, “I don’t want him to die, I want Fidel to suffer at least the half of what my family has suffered.” What did you feel at that time, when you heard this announcement, and what was your reaction when you found out that Fidel Castro had died?

At first, I didn’t believe it. When they called me from the US and my husband answered the telephone, I said to him, “He died again? I want to continue sleeping, leave me in peace.” Later when I got up and realized that it was true, it was like a sense of relief.

My husband asked me, what do you feel? I told him an enormous relief. The matter is that for me, it’s as if I had died spiritually. Besides, I already knew that he was ill and that he had lost his senses somewhat, given the things he would say. For me, he was like a shadow, a ghost. But that sense of relief was also because that symbol of the repression is no more, he doesn’t exist.

Does the death of Fidel Castro modify or change what 13 July 1989, means to you and your family?

To a certain point, I will tell you that for me, it is a relief that the one responsible, who decided the death of my father, has died, and in a certain way it gives me joy, I must admit. I cannot say that the death of him who ordered my father to be executed makes me sad, that would be absurd. That would be hypocrisy.

What does Raúl Castro mean to you?

For me, Raúl Castro represents the continuation of the system, with certain attributes different from those of his brother. They are two different people and have different command styles. The two have that ideologically dogmatic aspect, but perhaps Raúl is a bit more pragmatic, thus the changes that have been made on the economic level.

This is why I have been in favor of Obama’s visit, the opening of tourism, and of certain exchanges because it is the Cuban people who will benefit from this. Unfortunately, the regime takes advantage of this situation, but so does the average Cuban, those who have been able to start a business derive benefit and thus are able to help their families and other Cubans. And it is better than nothing, the problem is that it is not enough.

The country will not change until there are real political changes.

After the execution of your father, have you talked with or run into any of the children of Fidel or Raúl? If this were to happen, what would you say to them?

No, never, no. I didn’t know them. I never went anyplace where the children of Fidel Castro might be. I did meet two of Raúl’s daughters, but they were not friends of mine, we ran into each other somewhere. Mariela also studied psychology, so one time we coincided in some place.

How do you see Cuba’s immediate future?

In the short run, as things are now, the growth of tourism and Cubans surviving. This is what for now the government wants so as to not have social conflicts with the people because of the difficult economic situation.

At the political level, they are demonstrating that if they have to repress people for taking to the streets, for writing certain things in the blogs, they will do so. They will try to maintain control that way. We will have to wait and see if they realize that a country cannot develop without liberty.

Your family, like many others, is scattered around the world. Do you think that you will ever reunite again in Cuba?

I don’t know, the truth is that this is very difficult to answer. Seeing how things are, knowing that Raúl Castro has placed his children and relatives into the most important sectors of the country, taking control of the country with a view towards the future. Truly, I cannot give you a yes or no answer if I do not know what will happen. It would have to be a situation that would allow the return to a place with certain guarantees of justice and legality.

Would you delay, then, being able to give your uncle Patricio a hug?

For now, it will be delayed, if they don’t make changes and accept that one can go there having different opinions, which I have stated publicly outside. I don’t believe that I can go.”

Translated by: Alicia Barraqué Ellison