Translated from* from El Nuevo Herald, Ramón Fernández-Larrea, 8 November 2018

When one receives a novel – written by a friend who is a poet, or by a friend who has been and is forever a great poet – with the title Contracastro, one could never imagine that it is a love story, and not a pamphlet of accusations against power, nor the political testament of a worthy man, with a vertical and honest position.

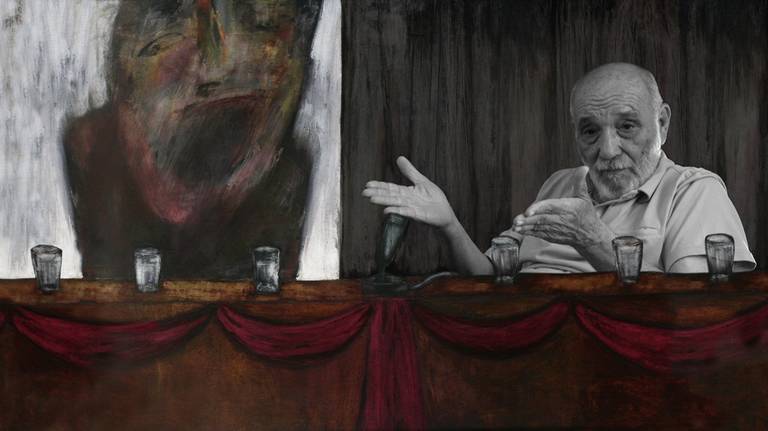

And if that novel is also the posthumous work of that poet friend, which is also like a last will, and also, a very old story that Rafael Alcides began to ruminate on in the convulsive first years of the 1960s, and which he spent his life writing and rewriting, the result is a kind of testament, because this novel could be, or is also, the novel of our lives.

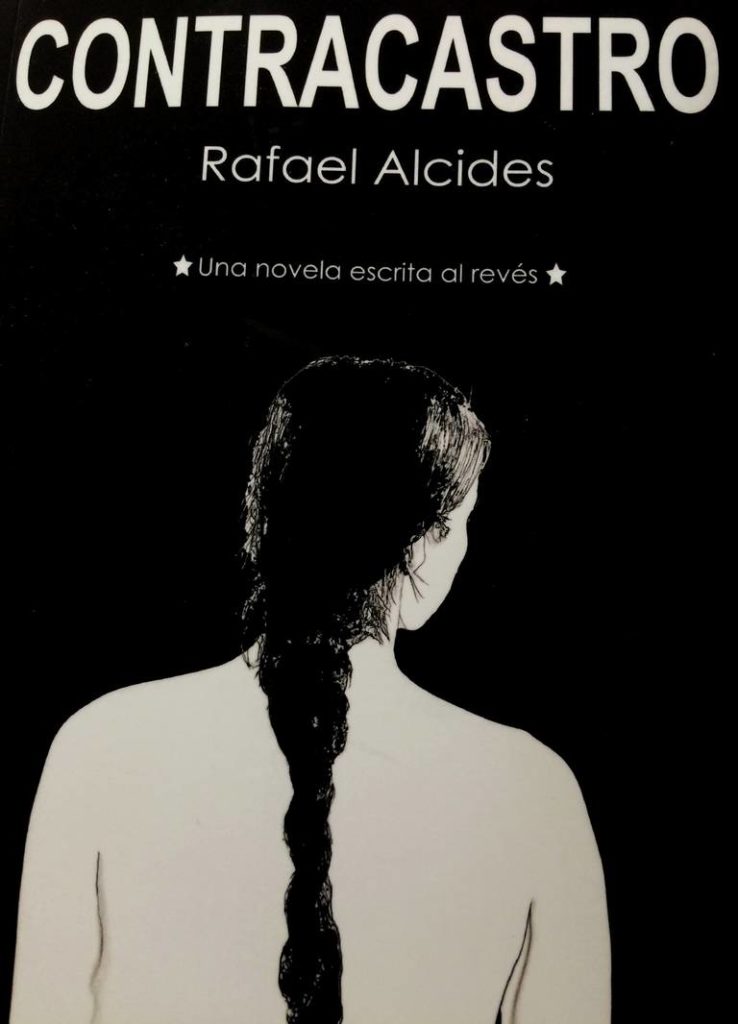

On the cover of the print edition it is noted that Contracastro is “A novel written in reverse.” Why? I suspect that it has to do with what Alcides himself says in the public history of the book: “In this second version the old love story is supported with very slight additions. Not so the context, this time evoked from today by Tom, already an old man, in a mega-Miami where he has been among the city’s forgers… For that first version, consistent with my political views of the time, the novel was nothing more than the many other pamphleteering-style texts of the time, against capitalism and the bourgeoisie.” continue reading

And Rafael Alcides continues telling us that “because of its title it frightened the Casa de las Américas officials when they saw it appear in the Literary Contest of 1965,” where “The juror Mario Vargas Llosa, who nominated it for a Prize, managed to obtain an Honorary Mention.”

What changed then? The world changed, Alcides changed. The years passed and the luminous future never arrived on the coasts of the island. Fatigue and disappointment arrived. And the masks fell from those heroes who wanted us happy all the time. And then came the time to tell, openly, the rending of the protagonists’ journeys to nowhere, the many protagonists of the other major novel, the epic of a people who emigrate, of families that are torn apart and walk through these worlds, without being able to tell their loved ones in a letter, all the love they still have.

Contracastro, published today by Eriginal Ediciones, is an inquest into Cuban history after 1959, told in first person, but in two alternating times, but, always in the background, it is a passionate story of love, sex, disgust and illusions, especially of lost illusions that the protagonist is capable of shouting to the four winds: “Burn down the world if they want, I have you.”

Contracastro is that then and this now. They are Tom and Carla in a provincial Miami that has been filled with Cubans who expect life to change in the next sixty minutes so that they can return to their country. A country that has already been filled with Russians, Chinese, Americans, abandoned houses, streets that will be, from then on, only in a bloody memory.

“Even though here in Miami they hate the word revolution,” writes the author, “it is here, nevertheless, where the Revolution really is. The Revolution with capital letters. In Cuba, the Revolution has already passed and what there is is the complete opposite of the ideals of democracy, present since the Guáimaro Charter of 1869.” … And at the end of that statement made by Tom, the protagonist, thinking like Rafael Alcides, or Alcides himself stuck in the skin and blood of Tom, one can read: “So while we can not return to Cuba, I will continue to consider myself a man from Guáimaro, a follower of Agramonte, a soldier of Céspedes, that is, a revolutionary.”

Contracastro is, in short, the legacy of Rafael Alcides, a man who lived and died telling his truths in Cuba today, and that was uncomfortable for the authorities, because honesty, in times of disappointment, is, at the very least, suspicious. Here the poet leaves us this intense story of a love that was and was not. A testimony against death, against oblivion. And we must read with gratitude to its author, to discover who we have been or who we are now. To know which side of History we are on. Or, better, to check, with pain and bitterness, which side of this story is ours.