English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

On 28 February 2008, the Havana regime signed, as a propaganda maneuver, the United Nations Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. At that time Raul Castro was seeking to legitimate his figure in the international arena and to project himself as a future option for the country.

On 28 February 2008, the Havana regime signed, as a propaganda maneuver, the United Nations Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. At that time Raul Castro was seeking to legitimate his figure in the international arena and to project himself as a future option for the country.

Six years later, Raul Castro can no longer be taken as a reformist. He now sells himself as the person who can close a chapter in Cuba’s history, offering the international community and the country’s allies a supposed controlled transition and offering his heirs as the only option for “governability” and “stability.” However, the hereditary group represents only the extension of a decadent system plagued by corruption.

Backed by this logic, a new anti-embargo offensive is gaining traction. Several actors and influence groups in the United States are seeking a blank check for the ruling elite and their beneficiaries. Elite who bear the main responsibility for the national disaster and the systematic violation of fundamental rights and freedoms. The offensive is also passing through Europe and Latin America. In the latter case, the main chess piece is beginning to be Brazil, now that Venezuela, in its decline, ceases to be a partner that guarantees stability in the medium term.

However, the recent “desertions” of Cuban professionals from the Brazilian “More Doctors” program, and its possible legal consequences, are evidence that the Brazilian situation is very different from that of the “Bolivarian brother,” and that it could quickly become more complex than expected. Brazil, with its ambition to establish itself as a regional power, is focused on a much longer term scenario. In order to sustain and widen its business presence, it needs a smooth transition process on the island, resulting in at least a stable free market system and full reestablishment of relations between the government in Havana and the United States. continue reading

On the other hand, negotiations with the European Union on a bilateral accord are moving forward, although according to statements from representatives of the EU, we’re looking at a process that could take at least two years. Sadly, some of the countries involved have bought into the ideas of “governability” and “stability” mentioned above, in the short term. Ignoring the terrible consequences of supporting a system sustained by corruption and state violence. Others, however, continue to demand a focus on human rights as a minimum guarantee for an eventual accord.

Meanwhile, the regime is silent before the European proposal, choosing a surgical repression on the island to avoid widespread discontent beginning to capitalize on open demands to the system. Repressing against activists is increasing and promises to worsen as the scenario becomes more complex.

At the same time, the Cuban Catholic Church, after a pastoral letter where it seemed to shift its questionable performance, continues to maintain a complicit silence in the face of repression. Recently the editors of the magazine Lay Space, a Catholic platform, declared that respect for human rights should not be a condition for relations with Havana. Regrettable statements from an institution that should assume respect for human dignity as its principle premise. No one should forget that legitimacy within a society is not achieved spontaneously.

To promote the false hope that a regime like the current one will evolve naturally into a modern democracy is at the very least naive, especially if what is blindingly obvious in Cuba is the construction of an authoritarian capitalism, sustained by State violence, corruption and and political patronage. To freely award room to maneuver to those who know no respect or ethics and who immediately show their criminal profile, is a mistake.

At the recent summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), one of the few statements that carried any weight was the request from United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon that the Cuban regime ratify the UN Covenants. The campaign “For Another Cuba,” an initiative begun on the island almost two years ago, is working in this direction, looking not only for ratification but for implementation of these international covenants. In the context described above, it would give us a magnificent tool for the political game inside and outside the island.

Clearly the results still don’t reach the hoped for level, but the more than 4,000 signatures, the work of promoting and distributing the “Citizen Demand” inside the country, the request of Ban Ki Moon, as well at the possible bilateral accord proposed by the European Union, create an excellent environment to continue to focus on this campaign.

Cubans on island are fed up with a totally decadent regime, but they fear being the target of the excessive violence of the State and its paramilitary groups. The Covenants as a civic demand is a campaign that, precisely because it involves ordinary citizens, carries an implicit international legitimacy. The demand for these covenants also provides democratic and friendly governments a target for a direct and specific demand to the Havana regime. At the same time, implementation would serve as a road map to advance the process of democratization through changes in the whole constitutional and legal structure, pegged to the binding nature of such agreements.

To demand the ratification and implementation of the Covenants is an interesting tool that we have barely explored. The “For Another Cuba” campaign has borne only its initial fruits. Those who want to help democratic change in Cuba from abroad, should pay attention to this effort undertaken on the island and take a careful reading of the interior pulse, so as not to contribute to efforts that are fracturing and dismantling. If we want to be objective and work with real variables, without creating false expectations, we have to observe the tempos that, on the island, are marked not only by the opponents, but also by the citizens.

Antonio Rodiles, 3 March 2014

PUERTO PADRE, Cuba. Within the systematic scarcity and increasing cost of daily life, the last week was marked by gaps in supplies. And although cement, steel and deodorants are missing, groceries are particularly missed.

More than the bread of the ration books that has gone missing some day or another, stomachs cry out for the “midnight,” for the one peso bun that could be acquired unrationed, along with the rationed bread, but that now is not produced for lack of flour.

For many without purchasing power, it mattered little during the several days that chicken was lacking in the “Hard Currency Collection Stores” (as the State itself named them). But it did matter, and quite a lot, when this week, after standing in long lines at the butcher shops, the ration of “chicken for fish” was not enough, nevertheless and being a rationed product, people had to content themselves with getting on a list for when a second round is produced, that no one knows for sure when it will be produced. “This is more of the same, ’when it’s not Juana, it’s her sister’,” grumbled one of those who did not get his quota of “chicken for fish.”

As is known, although Cuba is surrounded by the sea, on this island fish is a scarce product and is expensive, so that when it’s time to supply it through the ration book, the government substitutes some few ounces of imported chicken, which on many occasions, because of factors of corruption or bad administration, does not reach all the consumers of certain localities, adding to the discontent of the population because of … “shortages.” continue reading

Depending on the person from whom you acquire it, the time of year, the place, the quality of the product, and the species in question, in Puerto Padre a pound of fish or other marine product can cost between fifteen and forty pesos.

But if the meat products are scarce and expensive here, nevertheless and now being well into the third five-year period of the twenty-first century, nothing less happens with vegetables, which as early as the ’50s decade of the last century, in the case of rice, provided 24% of the Cuban diet, while beans made up 23%, according to data from the time by the National Institute of Economic Reform.

“I forget the last time that I ate red beans”

In one survey by the Catholic University Association, carried out among the rural Cuban population in 1957, it was found that only 4% of those interviewed mentioned meat as an integral part of their customary portion, 11.22% milk, only 1% admitted consuming fish and only 2.12% of those surveyed acknowledged eating eggs. The investigators asked themselves: “How does the farmer subsist with such deficient contributions of meat, milk, eggs and fish?”

The same surveyors from the Catholic University Association revealed the mystery in their report: “There exists a providential and saving fact: the bean, basic element of the farmer’s diet, is exceptionally a vegetable very rich in protein. In other countries where corn takes the place of beans in Cuba, deficiency diseases are very frequent. We can assure, without fear of error, that the Cuban farmer does not suffer more deficiency diseases thanks to beans.”

“Beans providential and saving? That would be in that period, when beans were eaten by the poor in Cuba!” exclaimed a doctor who on condition of anonymity explained to this correspondent how the local population, although not in all cases precisely underfed, mostly is malnourished by a diet in some cases insufficient and in others unbalanced.

In the bowl of the hands is more than enough space to fit the beans that, through the ration book, the consumer may buy for a whole month that, perhaps, suffice for one, two or three pots of rice and beans; the rest, for people who worked all their lives and got a very diminished retirement under socialist planning, must be bought at market price. “I forgot the last time that I ate a stew of red beans,” confessed a retired electrician.

Today, in Puerto Padre, a pound of red beans costs fifteen pesos; also white beans and garbanzos cost fifteen, and between ten and twelve for black beans; a pound of rice is five pesos, a small head of garlic costs a peso, a little more than a peso for a medium onion, five pesos for a bowl of peppers and between three and seven pesos a pound for tomatoes. Pork meat costs twenty-five pesos a pound.

The humble rice and beans that freed our poorest farmers from deficiency diseases today costs some forty pesos if seated at the table are two old people, two children and the man and woman of the house, something like the family of today; six mouths although with more old people and fewer children, the same number as the rural family from the fifties.

Maybe that is the reason for underweight and small children, why so frequently the consultation and waiting rooms of clinics and hospitals remain crowded. And they are not scarcities more or less of recent weeks, but from the last half century, where by decree, in Cuba meat came to be the chosen food, while the poor stopped eating beans because of socio-political circumstances, making Cubans more destitute, maybe worse fed than our ancestors, the aborigines.

Cubanet, February 26, 2014, Alberto Méndez Castelló

Translated by mlk.

Down K Street

My father had died, the good Armenak (1918-1998).

They laid him out at the funeral home at Calzada and K Street, not far from the municipal maternity hospital: the América Arias hospital.

Chapel K: it was my mother who chose the letter. It reminded her of her homeland, Armenia, which in native Armenian is actually spelled Armenika. It reminded her of my own father, the recently turned-into-cadaver Armenak. It reminded her of herself; a sudden widow named Takuji. In both cases, Saroyan.

My parents were cousins before being lovers. The Saroyan family excommunicated them: they did not tolerate such liberties within their clan. But they insisted.

Later, it was the occupied Armenika who excommunicated them: they didn’t tolerate liberties either within their false frontiers imposed by the Russians, the Turks and the Iranians. They insisted.

They crossed the continent and the ocean in one thousand and two layovers, until their ship wrecked by chance in another little homeland called Havana, bringing along with them Armenika as a stowaway, folded one thousand and two times along with the worthless currency in their pockets.

They insisted. But this time death at last excommunicated these two cousin-lovers from their so insistent passion for freedom.

At the most luxurious and lonely funeral home in Vedado, Havana, Cuba, my mother Takuji warned me:

Do not cry for your father, the good Armenak – she said. Cry for me, for not knowing how to die with him. Cry for you, for the shame that your parents have brought upon you; first, without a homeland, and now, without a family.

My mother Takuji pronounced it all in Armenian smooth and fragile, like her, a language that could not be any more dead even if no one in the world remembered it. It is the language of forgetfulness and of frustration as home: the same in the homeland as in the family, we no longer knew anything of our fate, uprooted with a country but without a destiny. continue reading

My mother Takuji continued:

-Vilniak- after centuries, she would pronounce my name in Armenian again – do not let your children get attached to their homeland, alright?

-Yes, mother- I replied.

-Vilniak- Takuji insisted- do not let your children love too much any son of the homeland, alright?

-Yes, mother – I replied.

-Vilniak -holding the weight of my head in her hands, as if she still did not give me any credit at all- do not allow your children to listen to you too much. Do not let them listen either to you nor to any of your mother’s words that will remain within you, alright?

-Yes, mother- I replied.

It was all uttered at midnight in her smooth and fragile Armenian, just like her weightless hands, just like Takuji all of my mother, just like the flaccidity of the dead man who was lying in the coffin, still, with his arrogant black tie made out of cotton from the homeland, dead, and yet actively listening to the two of us, as usual, unable to interrupt even our silence: Armenak or, as I hadn’t called him in ages, Papazik Saroyan.

At that time, my mother and I were Chapel K’s sole inhabitants, on the highest floor of Calzada and K street. In Vedado, 1998: Midnight.

It had also been centuries since the old Armenak died, just like the young Armenak. His terror of death made him play the role of a dying man for himself, even though he had always acted as a vital man in front of the others. So he exorcised his panic. So, and with the talking companionship of a sudden widow named Takuji.

My mother asked me to turn off the lights in the chapel. I went up to the light switch and jiggled it. Nothing happened. The lamp was set up to be permanently on.

With the help of a nail file, I was able to remove the only remaining screw in the breaker. I pulled the wires and they snapped easily. The light disappeared, or maybe it slipped away through the broken windows of the glamorous room.

I returned to my mother and the ceremonial candle, blended with the beeswax of our garden’s eternal beehive, it was flaming: Takuji had lit it.

-Vilniak- she had forgotten all the languages of the world and now she only counted on the Armenian: her native language, on Lake Van, 1921- no one ever dies his own definitive death. It will now be necessary to detach father from every single object, from every single space, and from every single memory, understand?

-Yes, mother- I replied.

-Vilniak-Takuji insisted- you know that no man is good as long as he doesn’t hear his name on the lips of a woman. And you know that every man ends up creating out of nothing she who will be his wife. You know it, and still, you resist. You do understand that this happens when you don’t love reality too much, right?

-Yes, mother- I replied

-Vilniak- holding with her hands the lack of weight of her own head, as if she still didn’t give herself any credit at all – why is it that we no longer speak Armenian?

She was right. We never spoke in Armenian anymore.

No, she was not right. We no longer spoke.

I raised my eyebrows. Stayed silent. I winced just to smile.

I closed my eyes. I bent over her chair and felt her breath. It was smooth and fragile, perhaps weary. Like smoked beech bark. In that precise instant I was woken by a shriek.

From the door of Chapel K, a certain functionary K was having a temper tantrum. He was shouting insults at us without restraint, pointing the rusty index finger of his left hand at us. How the hell had we turned off the light…? That was strictly prohibited by the administration. We were irresponsible, transgressors, almost to the point of deserving to be excommunicated by the funeral parlor: the sad old congenital old story of all Armenians.

Mr. K brought other Mr. K’s and together they restored the light: a lightbulb of at least one kilowatt. The big ceremonial candle was no longer shining besides the casket. Useless honey made out of processed flowers by worker bees.

My mother spit on her fingers and put it out. She thanked the State delegation in proper Cuban, and also in proper Armenian, she asked me to leave her alone for a good while. There was a mournful rancor in such propriety: a posthumous hatred that I hadn’t remembered in her.

-Yes, mother- I replied and left.

I left Chapel K for the little narrowed-shaped park on Calzada and K street, right where that republican funeral home’s building stood.

It was still El Vedado, 1998: just past midnight. Dozens of men were sleeping on the marble benches and over the lawn of dirt, all along Calzada street and almost to the Malecón. Their sleep seemed too deep for them to be able to mourn the dead bodies laid out on each floor of the funeral home.

A little old lady was selling coffee out of a thermos bottle and I went up K street, moving away from the sea. I was thinking about my parents’ life and about life in general. I remembered those books I was read to as a child about great Armenian characters. There are thirty-eight letters, and they are beauty to draw, but it’s even more lovely to pronounce them. I remembered the ever-snowy cap of Mount Ararat, just as seen from the capital city Yerevan: a now forgotten summit on the other side of the false border with the real Turkey. I remembered the genocide stories and the genetic hatred towards the word “Ottoman.”

Three blocks down I reached the grand avenue. I saw the little narrowed-shaped park nestled between Línea and K street. I got closer the bronze bust and it was, as usual, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881-1938): founding father of the Turk nation and the one who grieving bade farewell to the Armenian un-nation.

Peace in the country, peace in the world: said the plaque almost unreadable due to the lack of light. I felt the Latin characters in relief. Pax turka, I thought, and I sat down under the lamppost without a bulb or maybe it was a lamppost with a broken bulb, who knows.

I was thinking and thinking and every so often a hearse without a casket would pass by heading east, via K street, illuminating me with the yellow spotlight of its headlights. It was a disproportionate and frightening peace. I was thinking and thinking about a dawn in a new world, when finally the dawn broke over the old world on this side of the Atlantic.

The sparrows were cheeping with rage, they were expiating all the frustrations from the night before. A couple of them settled over Atatürk’s metallic bald head. They were playing, and they most likely would end up making love today. Many times: quickly, but many times. Literally like sparrows.

The male sparrow wiped its beak over the bust, showed the arrogant black tie around his neck one last time and flew off to no sky in particular.

The female sparrow shook her tail feathers, dropped a copious liquid dump, and flew off as well, in the same direction previously traced by her male partner. Heading west, towards the municipal maternity hospital: the América Arias, literally from Armenika to America.

I ran back, almost galloping down K street until I reached Chapel K at the lonely and luxurious funeral home on Calzada street.

My parents wake would take place on that winter Friday at eight-thirty in the morning.

I would be the only attending mourner and I found it impossible to give up now.

That’s it.

Translated by W. Cosme

20 December 2013

HAVANA, Cuba. — Roberto Pupo Tejeda, sacristan of the Catholic Church, was arrested and mistreated by officials of the State Security Department (DSE).

“I was in the Church participating in the Sunday Mass, and I went out to observe the walk of the Ladies (in White),” said Pupo Tejeda, referring to the customary walk that they hold on leaving mass, down Fifth Avenue, the women’s movement that demands from the government freedom for political prisoners and respect for human rights.

The religious man, was who taken in a PNR (National Revolutionary Police) paddy wagon along with six opposition activists to a police station, told this reporter after being freed in the afternoon that he was a victim of taunts and physical and psychological mistreatment on the part of officers of the DSE.

“They put the handcuffs on me too tight, and in order to take them off, a Security officer who identified himself as Camilo used a knife, and as if to intimidate me said that I should be calm because the knife had a quite sharp blade, and he might slip and cut me,” indicated the sacristan while showing the lacerations caused by the shackles.

According Pupo Tejeda, who was threatened by his oppressors with being deported to his native Holguin, 700 kilometers to the east of Havana, when he showed his card that identified him as a member of the Church, the DSE officers told him that that gave him no right to protect the Ladies in White. continue reading

“When I saw that they (DSE officers) rushed violently to arrest the Ladies, I put myself in the middle to protect them. That was all that provoked their ire with me,” he emphasized.

Berta Soler, leader and spokesman of the Ladies in White, confirmed to this reporter the arrest of the sacristan and reported that a total of one hundred activists from her movement were arrested on leaving the Santa Rita Church, as well as some ten opponents who had gone to offer their support.

She also emphasized that the number of women detained this Sunday is around 200 because there were arrests in all the provinces in which the Movement has headquarters.

The National Revolutionary Police’s (PNR) and DSE’s way of working in the arrest of the layman and more than a hundred opponents exposes the falsity of the words of the Catholic hierarchy and of the General President.

The wave of arrests took place in the morning hours this Sunday, February 23, when both repressive bodies carried out a raid against dissidents and opponents in the vicinity of the Santa Rita de Casia church located in the neighborhood of Miramar in Havana where the Ladies in White attend mass each Sunday.

Cubanet, February 24, 2014, Calixto R. Martínez Arias

Translated by mlk.

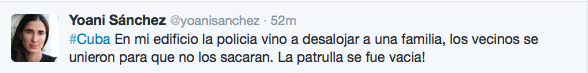

They say no one learns a lesson through someone else’s head, that we repeat the mistakes of others and stumble, over and over, on the same stone. Skeptics assure us that people forget, close their eyes to the past and commit identical mistakes. Venezuela, however, has begun to disprove that inevitability. Amid a reality marked by insecurity, shortages and inflation, Venezuelans are trying to amend a mistake that has lasted too long.

Taken over by Cuban intelligence, monitored from the Plaza of the Revolution in Havana, and ruled by a man who incites violence against those who are different, this South American nation now finds itself facing the most important dilemma of its contemporary history. Totalitarianism or democracy, those are the options. What is being decided in its streets is not only Nicolás Maduro’s permanence in power, but the very existence of an axis of authoritarianism and personal ambition that spans all of Latin America. A system that disguises itself with empty words in the style of “socialism of the 21st century,” “a revolution of the humble,” “the dreams of Simon Bolívar” and “the new left,” whose fundamental characteristics are its leaders’ lust for power, economic inefficiency, and the curtailing of freedoms.

But Venezuelan students have given Chavismo a dose of its own medicine. Young people and college students have been the driving force of the protests this time. Which proves that Miraflores has lost the most rebellious and dynamic part of society. Although the headlines in the government controlled press speak of conspiracies fomented from abroad, it’s enough to look at the images of the police and the armed commandos beating the protestors to understand where the violence comes from.

Venezuela is going through difficult times, like all awakenings. The oligarchs in red will not give up power voluntarily and Raul Castro will not let them so easily snatch away the goose that lays the golden egg. But at least we already know that Venezuelans will not walk the same road they imposed on us in Cuba. Meekness, fear, complicity, and escape as the only way out… those have been our mistakes. Venezuela doesn’t want to repeat them, it can’t repeat them.

2 March 2014

On the 27th, after serving his sentence, one of the “Cuban Five” spies was released and subsequently deported to Cuba. For several days, the official press and the authorities have launched a media circus, which starting today will grow. There are only three now serving sentences in U.S. prisons. I am sure, however, the manipulative media campaign will continue to talk about five. They have a lot invested in it and it would be like renaming an already known product.

This, ultimately, is nothing more than a publicity campaign like any other. In addition, it’s always cost the Cuban authorities time and work to react to reality. If once, many years ago, they were considered revolutionary, for decades now they have been profoundly reactionary.

It seems that time doesn’t pass in vain, and the old men of today find it hard to change something, fearing they will lose everything. It’s understandable: age no longer allows them to start over.

The issue of the spies, rather than an act of humanism, is a way to entertain a part of the population, so they forget their everyday problems, and to make some sense of the absurd protests and demands of the “government’s friends” abroad, which also assures paying tourists for the Cuban people, and feeling like they star in something, the more to the left the better, to be different to most.

There’s someone else who, I’m sure, contrary to their natural feelings, would prefer for the situation to continue, so that they don’t lose their “little goodies,” which they’ve been enjoying for years: their families. From ordinary unknown citizens, by the work and grace of the authorities, they have become public figures, who travel, dress well, give lectures, participate in events, receive awards, and who have resolved their problems of housing, transport, food and clothing, all at the expense of our pockets, because their “merits” shine by their absence, a non-being who on a new scale of values, is considered a “merit” to be a family member of a confessed spy.

These are some of the absurdities that persist in Cuba and that have disrupted our society, making the young and not so young people prefer to emigrate, and the old, condemned to their misfortune, dream of better days in the years they have left to live.

1 March 2014

A part of the roof of the newly repaired National Bus Terminal Havana collapsed, causing severe injuries to two young people who were awaiting the arrival of relatives from the Camagüey Province.

A part of the roof of the newly repaired National Bus Terminal Havana collapsed, causing severe injuries to two young people who were awaiting the arrival of relatives from the Camagüey Province.

The young people (Dayana Tejeda and Yisel Gonzalez, 23 and 25, respectively) commented that in the place where the collapse occurred there was no warning or sign of possible danger, on the contrary, was seen as a place recently remodeled. When I say, although they repair it, and repair it again… again … it falls it falls.

28 February 2014

The blogger Angel Santiesteban Prats now has completed one year in prison.

The blogger Angel Santiesteban Prats now has completed one year in prison.

It’s been one year today since Ángel Santiesteban Prats was detained in prison. The writer and netizen is the author of an informative blog, The Children Nobody Wanted, created in 2008, known for its open criticism of the government. On December 8, 2012, after an arbitrary and hasty trial, the Prosecutor declared Angel Santiesteban Prats guilty of the charges against him. Officially, he was condemned to five years in prison for “home violation and injuries,” in spite of the fact that no tangible proof existed. Thus, the blogger was transferred April 9, 2013 to Prison 1850 in San Miguel del Padrón (Havana), where on repeated occasions he suffered mistreatment and torture.

On February 18, 2014, Reporters without Borders learned that the National Association of Law Offices (ONBC) suspended his lawyer, Amelia Rodríguez Cala, so that she cannot practice in the courts for a period of six months. This considerably affects her efforts to have the journalist released. The lawyer is also in charge of the defense of two other dissidents, the musician Gorki Aguila, and Sonia Garro, a member of the Ladies in White, a peaceful protest movement made up of the wives and family members of the political prisoners, which in 2005 received the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Conscience.

“A year ago Reporters without Borders denounced these cruel and draconian practices. We urge the Cuban authorities to drop all charges against Ángel Santiesteban Prats and request that the journalist be released immediately,” said Lucie Morillon, Director of Investigations of the organization. continue reading

“The intimidation to which journalists are constantly subjected in Cuba is extremely worrying. Cuba occupies last place in the Americas in the World Classification of Freedom of the Press in 2014. It’s in place 170, out of 180 countries,” Lucie Morillon explained.

Although Ángel Santiesteban Prats is the only blogger currently serving a sentence in prison, the authorities continue harassing all the journalists who contradict the official propaganda. The correspondents from independent Cuban websites like Hablemos Press are frequently detained arbitrarily. Hours later they are freed. Other victims of this method are the journalist William Cacer Diaz, on February 14, as well as at least six other news providers: Magaly Novis Otero, Pablo Morales Marchán, Ignacio Luis González Vidal, Denis Noa Martínez and Tamara Rodríguez Quesada, in January 2014.

Ángel Santiestaban-Prats, who today sent an open letter to Raúl Castro, is listed in the Barometer of Press Freedom, as is José Antonio Torres, a correspondent in Santiago de Cuba for the official daily, Granma, imprisoned since May 1, 2011.

Published in Reporteros sin Fronteras (Reporters without Borders)

Translated by Regina Anavy

28 February 2014

Mr. Ruler:

On February 28 I completed one year of unjust imprisonment, after a trial where I demonstrated my innocence with multiple proofs and witnesses. In exchange, the Prosecutor couldn’t present one single consistent proof against me, except the malicious – in addition to being ridiculous – one of an expert calligrapher who, after having ordered me to copy an economic article from the newspaper Granma, the Official Organ of the Communist Party, gave an opinion that the height and slant of my handwriting showed I was guilty.

All this happened four years after the supposed event, where they saddled me with a crime that I didn’t commit. To make things worse, this whole circus that went down against me was corroborated by the henchman Camilo, an official of State Security, long before the Court passed sentence.

Being detained – after a demonstration of support by other compatriots in opposition – this official announced to me before witnesses that I “would be sentenced to five years of privation of liberty,” a declaration that he published on the Internet, one month before the official pronouncement of the Court, an organ that should be impartial, should act independently, but that in addition to clearly following the rulings of State Security, perpetrated another flagrant violation during the judicial trial, upon adding to my penalty one more year than the maximum established by the Penal Code.

My case, like many others, shows that after the coming to power of your family, the Castros, there isn’t even a minimum of independence among the legislative, executive and judicial powers, which exists in all nations that are truly democratic.

These powers are managed by you at your whim and convenience. And history shows that when these powers are manipulated by the same entity, whatever the ideology, we are dealing with a dictatorship, where the only thing left to us is the possibility of interrupting and having influence with our opinions in the fourth power: communication, the news, achieved thanks to the development of the Internet, and to thereby circumvent your iron control on the media. And for that I have been punished. continue reading

Since my incarceration I have been physically and psychologically tortured; on several occasions I have suffered cold in the concrete beds of your cells, beatings from your henchmen, and I have rejected all your proposals that I abandon the national territory or desist from my ideals of freedom for my country.

I want to remind you that before opening my blog, The Children Nobody Wanted, where I only said what I thought about the terrible circumstances of the lives of my people, I was an exemplary citizen who, thanks to the literary talent that God gave me, won prizes and recognition from national and international cultural institutions.

But, General, one day I discovered that the ethical price I was paying to be seen as an exemplary citizen for the totalitarian society that your family has imposed on Cubans was too high for my soul and my time in history. I had to overcome the fear of repression with which the institutions of indoctrination created by your family educated me from my birth.

I decided to overcome the fear implanted by you in the generations of Cubans who have grown up under this failure that you call “Revolution,” and, in particular, the muzzle on the conscience of the artists who mainly pretend to support the socialist process that you command, but later are heard criticizing the Regime under their breath, because, apparently, the Cuban people have preferred to take the easiest, but the longest, road.

This reality of social pretense became for me an insupportable moral burden. I didn’t want to continue doing what they were doing – and still do – this large part of the Cuban generations who have been educated under the law of the cynicism of survival, pretending what they don’t feel.

My conscience lead me to open my blog, The Children Nobody Wanted, and beginning with this event, I signed my death sentence, as your repressors have told me on several occasions.

Expressing a critical opinion as a citizen about the social process that you lead is the only “crime” I have committed, and I accept it.

From this moment I have been prohibited from traveling abroad. They have marginalized me from all national cultural activity, and as a very important detail, just after writing you my First Open Letter, a judicial farce began against me for a crime I supposedly committed four and a half years ago.

Doesn’t this seem like a suspicious coincidence?

Now, one year later, I write you this Second Open Letter, running the risk of unleashing even more your cruelty against me, and even, at the risk of losing my life – although it would be so easy for you to accomplish that, only a snap of your fingers and it would happen.

I urge you to do it, by any of the methods you have applied in more than fifty years of dictatorship against many of those who have opposed your plans: a suspicious terminal illness, an assassination because of a supposed brawl with a common prisoner, or an accidental fall, to cite examples.

Your masters, the Russian KGB and the East German STASI, have taught your stooges well in how to eliminate “enemies” while leaving their guilt on the terrain of speculation.

I assure you, luckily for me, that what I was born to do in this life has already been accomplished, because my ambitions are small. This helped me to decide to change my status, my literary future, what some call “to boycott my fate,” since to sacrifice the well-being and happiness of my children, to limit to the extreme my publications and artistic life, I have done only in exchange for one humble aspiration: that my biography show that I struggled for the freedom of my country and against the dictatorship of my time.

That is enough; it’s sufficient for me.

It only remains for me to add that thanks to you and your repressive machinery, I have learned how much capacity for suffering I can stand; I have verified that ravenous hunger, the cold and the beatings were crushed by the force of my ideals and feelings.

I have seen that it’s worthy to suffer for the rest upon seeing them abused by the power that you hold, hurt by the jailers. I have learned to share the last crust of bread with those I live with in the cells to whom I have been drawn.

I have learned to defend my ideas above the hunger and the illnesses, and I have convinced myself that there is no way of making me change my ideas about what I consider just or about the wide universal right that I have to freedom of expression.

I am grateful for this miserable life to which you and your “humane socialist system” have confined me, because I have grown before every obstacle and, above all, because with each test I have become a better human being.

I have taken advantage of the time to write several books which I have collected in a safe place, and in part of them I describe the terrifying and inhumane reality inside your prisons.

The ideals that I brought with me to prison have been strengthened, they have revived with an unimaginable force. For injustice and impunity, I count on you to this day. For telling the truth without fear of your reprisals, I count on me.

May God forgive you,

Ángel Santiesteban Prats

Lawton Prison Settlement, February 2014

Translated by Regina Anavy