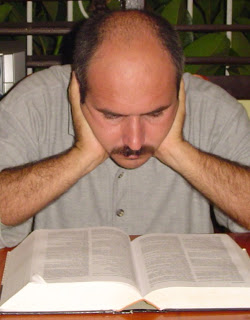

14ymedio, Havana, 16 August 2018 — Two weeks ago, Ileana Álvarez and her husband Francis Sánchez went into exile in Spain. Both are known for their prolific work as poets, writers and essayists. They decided to leave the country, along with their youngest son, due to the “pressures and threats” to which they were subjected by the authorities.

Álvarez founded the magazine Alas Tensas [Tense Wings] in 2016 , an independent media that explores issues such as gender violence in a country that for decades has distanced itself from discussions about the role of women in society. Sánchez, meanwhile, is the author of more than 20 books published in Cuba, Mexico, Spain and the United States. From Ciego de Ávila, in the center of the country, he founded the magazine Árbol Invertido [Inverted Tree] in 2005, which he conceived of as a space to reflect the needs and voices of creative communities outside of Havana.

From Madrid they answer 14ymedio’s questions about the reasons that led them to make such a drastic decision.

What were the circumstances that led you to make this decision?

Francis Sánchez: Actually, “the circumstances” would be our entire lives. I have grown up like any Cuban of this era under the heavy burden of authoritarianism, also suffering that alienation from human relationships when many people around you live in fear, with masks and lies, something I never wanted to adapt to. continue reading

I always felt a little proud of the challenge of residing, resisting in a small city in the interior, irreverent, solitary, and achieving in these adverse conditions my personal goals, even if they were not the greatest, such as making a family, doing literary work, having a blog or founding an independent magazine. I found myself frequently in the midst of censure and other unpleasant situations. It was an exhausting daily resistance, sometimes telling myself that this was my destiny.

Nevertheless, in the last months, since March, we began to be the targets of great harassment. Ileana was interrogated and threatened by State Security, they interviewed me upon entering the country and they confiscated my laptop. In a short time, we became targets for State Security, their intimidations were very strong, they forbade us to leave the country several times, coerced our friends and collaborators, and we began to notice dangers that even touched our children.

We realized that we could be trapped in the fallacy of some kind of common legal case*, I doubt that then we would have had a way out or to get support, something that I am more convinced of today. Pen América published a dossier on the risk of our situation [Status: Threatened]. But, ultimately, we felt extremely vulnerable and isolated. I saw clearly that sometimes resisting for the sake of resisting does not make any sense. My goal and my victory is in creating, and I decided to take advantage of Spanish nationality to provide a period of tranquility for my family, and maybe a better future for my children.

Ileana Álvarez : I have always believed in the possibility of change, with faith that the future will be better, in the same way that I believed in the commitment and responsibility of the intellectual with her time. This led me, from my years as a Philology student at the Central University of Las Villas, to create or ally myself with literary projects and the founding of magazines such as Imago, Videncia, Árbol invertido and Alas Tensas, where I have expressed my ideas and conceptions about culture and society.

However, the harassment, the ideological and psychological harassment suffered in recent months by an independent feminist magazine made my faith falter. Far from what was happening in the world, intersectional feminism, not at all essentialist, even from the culture that made Alas Tensas, had become dangerous for the structures of the patriarchal power existing in Cuba.

The situation became particularly intolerable, we could not — under that harassment, which included our collaborators — continue to develop our work. I felt as a woman, mother, journalist and poet who lived in the provinces, even more vulnerable and alone. I saw that my children were no longer safe, and that is very painful and disequilibrating for a mother. The situation was untenable and I realized that I needed a break.

There is something that I would like to add, which aggravates the state of vulnerability of many Cuban feminists: feminist activists are rejected from different political extremes. For the Government and its institutions, feminism is a falling backwards to bourgeois liberalism, while for a good part of the opposition, which has not shed its macho thinking, it is not to be trusted because of its leftist tradition. Both positions forget all the gains that feminist struggles have brought to the world.

What risks did you face staying on the island?

Ileana Álvarez : I was facing greater harassment, since some of the serious threats made to me by State Security became a reality and affected loved and innocent people; I was facing more psychological and emotional damage than I had suffered to date and that was seriously affecting my physical condition; I was facing greater social isolation than I was already experiencing in my city, and other ignoble practices that the blind mass performs, and losing my right to enter and leave my country whenever I wanted. That and more, because I was going to continue doing feminist activism from Alas Tensas.

What is the current legal status under which you are in Spain?

Francis Sánchez : I obtained my Spanish citizenship, through the Law of Historical Memory. It was a process I started in 2010. I have come to Spain, therefore, with a Spanish passport, our son will soon receive Spanish nationality by choice, while Ileana will obtain her residency.

What will happen from now on with the projects ‘Alas Tensas’ and ‘Árbol Invertido’?

Ileana Álvarez and Francis Sánchez : So much resistance we have encountered to carry out personal, independent projects, such as the cultural medium Árbol Invertido (since 2005) and the feminist magazine Alas Tensas (since 2016), only confirms that they are our raison d’être, even to our regret, they define us, and we will continue with them always, in the midst of new and unpredictable difficulties such as those we will encounter in Madrid.

The attacks we received signify a kind of praise and recognition of the work we have done. Without a doubt, Cuba needs alternatives for free expression. We have always thought that our magazines were a space of freedom, a kind of virtual country, ideal, without censorship or rancor, as was our literature, because in such deteriorated internal and social conditions we needed to invent an island better than to inhabit, and the ubiquity of the internet allowed us to do that very well.

Now, for other reasons, perhaps we need more than ever to keep that tunnel open to the utopia of an island with everyone and for everyone. These projects are nourished by the Cuban reality, and by collaborators and readers who, for the most part, are still on the island. Cuba needs projects like Alas Tensas and Árbol Invertido.

What would have to happen to make the decision to return to Cuba?

Ileana Álvarez and Francis Sánchez: Our family and our house are there, along with other people and places we love. We have the right to be there, to never have left and to return as soon as we decide. We are traveling legally, and we prefer to think about our departure, as well as our probable return, as part of the natural freedom of movement of human beings.

For those of us who have positioned ourselves in favor of freedom of expression and democracy, exile does not have a pejorative weight. But, in the contemporary global village, Cubans also take advantage of multiple opportunities that come from abroad, a fellowship, a master’s degree or a work contract, and today many intellectuals and alternative journalists reside outside of Cuba, sometimes temporarily, without this being a straitjacket.

Of course, we would like to return to a different country, where real feminist activism is not a threat, independent journalism is not demonized and the freedom of expression of artists is not throttled by the State. The ideal would be to return to a country where nobody is afraid to say what they think. By the way, if we were to choose, we would then find a society in which two abominations do not exist: the death penalty and acts of repudiation. In short, that Cuba we dream of, and that all Cubans, regardless of our differences, and wherever we are, we have the right to build.

How do you imagine life in exile now?

Ileana Álvarez and Francis Sánchez: The Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet said: “Exile is hard work.” Socrates preferred to drink the hemlock rather than be expelled from the city. Those who manage the life of generations and the time of the island, have abused that master key. “Outside,” for now we barely have had time to imagine, we have very little apart from our will, proven by where we come from. We are willing to work on anything and start from scratch as millions of compatriots have done, for as long as we consider necessary, and return to Cuba when it seems appropriate.

A message for those who pushed you to make this decision?

Ileana Álvarez and Francis Sánchez : We do not think about the faces of “those” of flesh and blood. The evil lies behind and above simple instruments. But, a message, with all my heart, could be: “Thank you.” It could also be: “We will continue discussing in eternity,” or “Violence is not an argument.”

We have always clung to positive emotions, we decide what we are. In short, for us, poets who try to live in coherence with our consciences, it is rather stimulating to feel that we are again at the beginning, not at the end. We remember Pablo Neruda: “You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot stop the spring.”

*Translator’s note: Sanchez is referring to the practice of falsely charging dissidents with common crimes (ranging from domestic violence to murder) rather than with political crimes, to prevent people from being considered “political prisoners” by international human rights organizations.

_____________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.