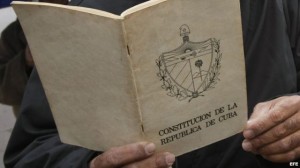

On the 29th of October of 1897 in the pasture of La Yaya, in Sibanicú, Camagüey, the drafting of what would become the last mambí Constitution came to an end. The resulting text represented a qualitative leap forward in Cuba’s constitutional history. This was due to the inclusion, for the first time, of a dogmatic part that included the most advanced individual political and civil rights at the time: habeas corpus, freedom and confidentiality of postal communications, freedom of religion, equality before taxation, freedom of education, right to petition, inviolability of the home, universal suffrage, freedom of expression and the right of assembly and association.

On the 29th of October of 1897 in the pasture of La Yaya, in Sibanicú, Camagüey, the drafting of what would become the last mambí Constitution came to an end. The resulting text represented a qualitative leap forward in Cuba’s constitutional history. This was due to the inclusion, for the first time, of a dogmatic part that included the most advanced individual political and civil rights at the time: habeas corpus, freedom and confidentiality of postal communications, freedom of religion, equality before taxation, freedom of education, right to petition, inviolability of the home, universal suffrage, freedom of expression and the right of assembly and association.

This result was determined by multiple causes; particularly because the always-present interdependence between development and individual freedoms in every social project is reflected in the constitutional history of human rights. continue reading

For example: the Magna Carta imposed by the English nobility on John Lackland in 1215, the Habeas Corpus Act of 1674, the English Bill of Rights of 1689, the United States’ Declaration of Independence of 1776, and France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. These, among other documents, spread at a global level, along with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, put into force in 1976.

Cuba’s constitutional history began in the colonial period with the Project for an Autonomous Government in Cuba, drafted in 1811 by Father José Agustín Caballero. In 1812, Joaquín Infante, an attorney from Bayamo, drafted the Constitutional Project for the Island of Cuba, and in 1821, priest Félix Varela drafted the Project of Instruction for the Politically and Economically Autonomous Government of the Overseas Provinces. Later, during the wars of independence, in a context of contradictions between military and civil law, Cuba’s constitutional history was enriched by the mambí legislation.

On the 10th of April of 1869, the Guáimaro Constitution, in which an emphasis on civil law was imposed, was signed. This Basic Law based on a tripartite division of powers, gave the legislative power to a House of Representatives that had the authority to appoint and depose the President of the Republic in Arms and the Commander-in-Chief. The executive power was in the hands of the President, and the judiciary was independent.

Despite the facts that it was created during the war of independence and that the House of Representatives was granted authority over the Republic’s sovereignty, the Constitution’s emphasis on civil law? allowed for the rights and freedoms of all Cubans to be protected? in Article 28 as follows: “The House cannot attack the right to freedom of religion, freedom of the press, peaceful assembly, education and petition, or any inalienable right of the people.” According to Dr. Oscar Loyola, in Guáimaro, the possibility of a military dictatorship, always latent in a historical process of this nature, was programmatically eliminated.

From the 13th to the 18th of September of 1895, at the rebirth of the war of independence in Cuba, a new Constitution was drafted in Jimaguayú, which reflected the experience gained from The Ten Years War. As M. Sc Antonio Álvarez expressed, three groups of interests intersected in this document: predominance of military power, José Martí’s principles and an exacerbated anti-militarism, between those who had a pact of interests reflected in that the highest authority of the State was concentrated in a Council of Government with powers to dictate all matters relating to the civil and political life of the revolution; in other words, this body had executive and legislative powers. Article 24 limited the validity of this Constitution to a period of two years.

In compliance with this article, a new Constituent Assembly met in La Yaya from the 13th to the 29th of October. The resulting Constitution readopted the civilian character from Guáimaro. It consolidated the organization of power in civil institutions, and closed the cycle of the type of constitutionalism that had resulted from the wars of independence (Guáimaro, Baraguá, Jimaguayú, and La Yaya), which, obstructed by the American occupation and the imposition of the Platt Amendment, gave way to the Republican Period. The best evidence of the scope and importance of La Yaya is that the civil and political rights enshrined in this document were readopted and enriched in the constitutions of 1901 and 1940.

The advocates of the supremacy of militarism wondered: Why did the Basic Law include a dogmatic part whose immediate purpose was to serve as judicial instrument during wartime? The answer to this question had been already answered in several writings by José Martí, for whom the Republic had become the definition of the democratic soul of the nation.

Martí established a logical genetic relationship between war, independence, and the Republic, where the first was a bridge to reach the last one. This is why he clearly defined the purposes of the war, so that after that conquest of immediate independence, these then would become the seeds of tomorrow’s long-lasting independence. He believed that, in times of victory, only the seeds that were planted in times of war thrive.

In his speech, “With All and for the Good of All,” delivered in November of 1891, Martí said: “Let’s close the doors to a Republic that is not founded on means worthy of the decorum of men, for the good and the prosperity of all Cubans!” In April of 1893, he expressed: “That is the greatness of the Revolutionary Party: that to found a Republic, it has started from a Republic. That is its strength: “that in the work of all, are the rights of all.” In the Montecristi Manifest, he wrote: “Our motherland must be built, from its roots, upon feasible ways that are self-born, so that a government that lacks truth and justice cannot lead it to the path of favoritism or tyranny.”

The post-1959 events are what best proves the importance of the civil law emphasis of the Constitution of La Yaya. After 17 years of government under The Basic Law of the Republic of Cuba, the Constitution of 1976, which abolished the Constitution of 1940 and made political and civil rights were subject to the legitimization of the Communist Party as the maximum leading force of the State and society, was approved; something alien and contrary to the day when a new Constituent Assembly, elected by the people, assumes the task of drafting a Magna Carta that includes our constitutional heritage and shapes it into the reality of today’s Cuba and of the winds blowing across the universe.

Originally published in El Diario de Cuba

Translated by: Chabeli

1 November 2012