Taken from OnCuba, by Cecilia Crespo

In November last year, the French channel France O aired the documentary “The Marble Cow” by the renowned critic and film producer Enrique Colina. It was only shown once in Cuba, during the last International Festival of New Latin-American Cinema held in Havana.

Some days ago, a Spanish friend who saw Colina’s documentary asked me about Ubre Blanca. For those who do not know, this was a cow that turned into a media phenomenon in the 1980s. In only one day, it produced 110.9 litres of milk and 27,674.2 litres in 365 days of lactation, pushing Arleen, the North American champion, out of the Guinness World Records.

At that time, many people thought that with this cow, Cuba’s economic problems would be solved. The dream fell apart several months later. Colina, a Cuban master of documentaries, took advantage of the story of Ubre Blanca (White Udder) to metaphorically discuss other failed economic plans carried out some decades ago on the island.

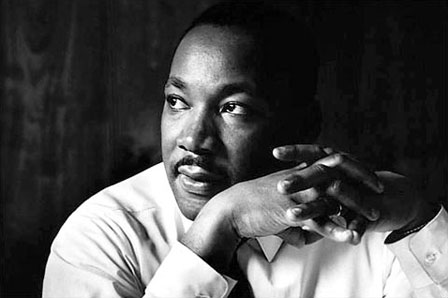

Given the insistence of my friend to know more about this documentary, I decided to contact Enrique Colina. We began by talking about “The Marble Cow”, but this wound up being just a pretext for one of the most lucid intellectuals of our country to talk to us about how he sees the present and the future of Cuba.

Tell us about “The Marble Cow” and its relationship to the Cuba that Cubans experience.

The starting point of this film is the never-ending phenomenon of gauging facts that are somehow exceptional and converting them into paradigms of reality. The documentary expresses what one of the people interviewed says about the Cuban press: it is more propaganda than thoughtful, and it does not offer the symptomatic analysis of reality that we need as citizens.

This is currently being demonstrated in what is happening with the exorbitant price of cars. Everyone in the streets is talking about it and nowhere has the media referenced this event. After yet another meeting of the Union of Journalists, in which they all speak in favor of reflecting reality, nothing ever appears in this respect.

The media phenomenon of Ubre Blanca in the 1980s was impressive. Some years after the propaganda paraphernalia that surrounded its appearance I was on the Isla de la Juventud, where I visited the workshop of the sculptors who made the marble cow. It had already been finished for several years and the authorities had not yet decided where to place the sculpture, whether at the entrance to the airport, in a public square, or at Ubre Blanca’s original home. The sculptors were anxious to get the statue out of the workshop because it took up a lot of space.

From that moment I had the idea of making the documentary, in which this cow could become a symbol, a metaphor of a deranged reality. It is a disorder that even today continues to be represented officially in the cult of a hero placed on a pedestal that, even though there is an overflowing trash bin at its base, is always framed so that only the hero and pedestal appear. continue reading

We are living in a time that is the expression of this obstinate deformation and which remains irreversible as long as there is no recognition of the causes and people responsible for the mistakes they have made.

The story of the cow is the magnification of an exceptional natural phenomenon, which, however, does not deny the fact that serious scientific work was done. It was explained that experiments were made to create cattle that were resistant to heat and cows that produced a lot of meat and milk.

In 1981, an extraordinary milk production process was achieved. What happens is that to manage this production with F2 animals, the result of crossings that were made and in which there is a scientific reason and success that I appreciate, there had to be favorable conditions.

A lot of milk was produced in the 1980s because there was economic support to sustain this type of national cattle raising. But this support was due to Soviet help and not to an internal economic structure that reproduced the necessary wealth to sustain this type of plan.

We have lived embracing myths. And one of the aims that I lay out for myself as a filmmaker, in the few years that I may have yet to live, is to contribute to recovering some of the historical memory of this process.

Not the memory of the transcendent facts praised and stained by official rite, but rather the memory of the daily routine of a national life seen from the ground and not from the wishful illusion of disastrous consequences, in other words, those rains that brought the type of mud that is precisely what this documentary is about in a certain way.

Ubre Blanca is also the 10 million ton sugar harvest. It is the Havana Belt, the micro-jet banana, the zeolite… it is a little of all of these economic plans that in a wishful way, and I do not doubt with the best intentions, failed.

Wanting to rapidly detach itself from underdevelopment and without its own wings to fly, reality has referred us to the magic mirror, that of the queen in Snow White, which the generation of filmmakers in the 80s critically compared Cuban television to, until one day the mirror told the queen she was not the fairest of all and she broke the mirror.

Tell me about Cuban cinema. What do you consider to be the positive and negative aspects of current film production in Cuba?

Cuban cinema is composed of different generations and many different views. It is in a delicate state of health due to a lack of material goods, and we all know it is difficult to make a film without money.

But on the other hand, another factor has facilitated filmmaking: the advent of new technologies. They are now talking about the protests made by a group of filmmakers against bureaucratic aspirations to restructure the ICAIC (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) without consulting the producers.

One of the things protesters are aiming for is the legal recognition of independent production, since the ICAIC does not have the resources it once had when between 6 and 8 full-length films, some fifty newsreels, and other documentaries and animated films were made every year.

This ended, the bubble exploded, and because of this we have to recognize that one has to fight independently, but with a national institution that is neither patronizing nor censorial, but rather a promoter of incentives to maintain and defend, with its collaboration, that film culture that the Revolution stimulated.

I think that interesting things are coming out of this. I recently saw works by two young producers, Melaza and La Piscina, and they seemed quite suggestive. Both expose conflicts in current reality that must be tackled from different esthetic, human, and critical angles.

This new generation has its worries, its sensitivity, and it is facing a very contradictory reality that projects an uncertain future. There are documentaries in the Young Directors Film Festival that reveal this critical, anti-conservative, and polemic view of unstated topics and taboos.They do not turn their backs on conflicts and because of this, because they are uncomfortable, are not made public or shown on television.

Another problem of Cuban cinema is its exhibition. What condition are the cinemas in? Where is the money to equip and repair them? One can make independent films, but what then? Where to show them? They took away private 3D cinemas and what is the alternative? Positive changes have been seen, but all the changes must be recognized as being due to citizen participation, discussion, and forecasting.

Many times measures are taken to stretch and shrink because they do not foresee the consequences of of their decisions. It is as if we are trapped in a cage; the mess is not only material but also ideological, and the modification that we need is not only tactical and partially economic, but also political. Paraphrasing Raúl, the only commitment that Cuban cinema has is to maintain a serious and thoughtful artistic dialogue with the national reality.

Colina, you speak not only about past, present, and future Cuban cinema, but also about Cuba. Do you consider yourself a filmmaker that questions the society in which you live?

Colina, you speak not only about past, present, and future Cuban cinema, but also about Cuba. Do you consider yourself a filmmaker that questions the society in which you live?

Utopian obstinacy turns dreams into a nightmare if there is no criticism, no debating of ideas. I share the humanist ideas of the Revolution and I obsessively rebel against the practice of its distortion.

In the 1980s, I dealt with esthetics, where I addressed the theme of beauty as a need to reaffirm the human condition. Socialism, in spite of developing education and culture, has always neglected the teaching of esthetic sensibility in the appearance of dynamic urban surroundings.

Today associated with poverty, loyalty has been imposed as an expressive master of the crisis. You see places where everything is ugly and poorly made, which is also reflected as a symptom of distortion in botched jobs and “I will also make you cry”, referring to the poor quality of state services.

In “Neighbors” I highlighted the conflicts of living together and the social indiscipline tolerated by an irresponsible permissiveness, etc. Anyway, I have made different documentaries that reflect problems that already existed in the 80s and which have degraded to terrible levels today.

Beyond calling myself a critic, I think I am a person who lives in this country and who sees this reality clearly and without prejudice at the cost of experiencing bitter disappointment. Far from paralyzing me, it compels me to protest. It seems to me that there is nothing exceptional in what I do. I have an opinion and it is my right to express it.

It is a shame that this attitude is not more widespread. My point of view is that we have made ourselves a type of citizen that has not developed an elemental civic feeling. To be revolutionary has historically meant obeying, following leads, completing the tasks assigned, and it has relegated to demagogic rhetoric that…

Translated by: M. Ouellette

24 January 2014