![]() 14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 4 May 2015 — The reunion of five friends on a roof terrace in Central Havana is the thread on which Return to Ithaca’s plot rests. Leonardo Padura wrote the screenplay and Laurent Cantet directed this French film about Cuban topics.

14ymedio, Miriam Celaya, Havana, 4 May 2015 — The reunion of five friends on a roof terrace in Central Havana is the thread on which Return to Ithaca’s plot rests. Leonardo Padura wrote the screenplay and Laurent Cantet directed this French film about Cuban topics.

The film is currently circulating underground among Havana moviegoers, preceded by the best possible presentation: the official censorship that prevented its showing during the latest edition of the Latin American Film Festival, held in Havana in December, 2014. However, Return to Ithaca has been shown at the Charles Chaplin auditorium in Havana, in the framework of the French Film Festival, being held throughout the month of May.

The film has become the cultural phenomenon of the moment, largely “by the grace of” the official censorship in a country where direct or veiled criticism of the system remains an event, even when — as in this instance — it makes use of worn-out clichés and platitudes.

The second element in its favor is participation in the script by Leonardo Padura, who has, in recent years, become a fashionable writer inside and outside Cuba, especially since the success of his greatest achievement to date, the novel The Man Who Loved Dogs, a best seller that has sparked what has been termed in literary cliques as “Paduramania”.

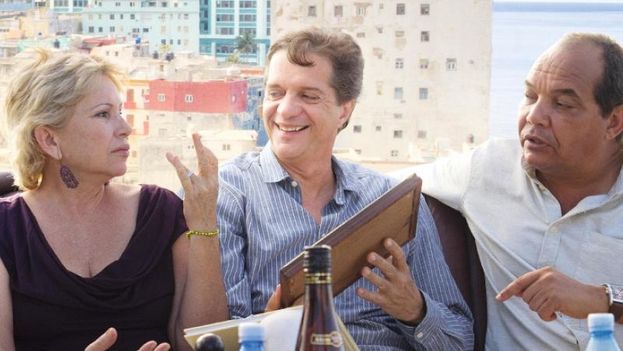

Almost the entire cast of the film is composed of experienced and well-known actors such as Isabel Santos, Nestor Jiménez, Fernando Hechavarría and Jorge Perugorría, though it should be noted that the actors do not always come out unscathed from the setbacks imposed on them by the script’s faults and the confinements of the straightjackets their characters embody.

Apart from that, Return to Ithaca is but a mediocre movie that, perhaps with the pretense of presenting the drama of a generation born and raised in the deceit of half a century of a failed Cuban socialist revolution, barely manages a pathetic caricature summarized in the five life stories of resentful and frustrated individuals who do not even come close to representing the spirit of their generation.

The plot, settings, characters and actions turn on stereotypical machinations to the point of lacking credibility and dramatic force. The script is somewhat forced and artificial, in addition to widely appealing to the ease of profanity and vulgarity that, for some, has become “the recourse of Cubanism” in film and literature. It seems that, regardless of what level of education or schooling we Cubans may have, we can only express ourselves through the use of obscene language.

Neither do the characters’ stories reach sufficient depth. They are stiff, synthetic, lacking nuance and not very credible, all of which fail to convey their personal conflicts or to move the viewer’s emotional fiber, thus establishing an atmosphere of distancing between actors and spectators bordering on rejection.

Plot, settings, characters and actions turn out stereotypical machinations to the point of lacking credibility and dramatic force

Amadeo (played by Nestor Jiménez) is the reason for the 50-something reunion of this group of friends. He is a writer who left Cuba to go live in Spain for reasons his friends only find out at the beginning of the movie.

So Amadeo decides to stay in Spain during a working trip to avoid betraying his friend Rafa (played by Fernando Hechavarría), a talented painter who has been harassed and marginalized because of his lack of political commitment to the system. When the reunion takes place, Rafa, who has never asserted himself over the hedge of official censorship, feels bitter about having to survive producing paintings lacking in artistic value for sale to tourists, while Amadeo embodies the misfit émigré who has never been able to write again since his departure, and is now determined to stay in Cuba.

Tania (Isabel Santos) is a doctor specializing in Ophthalmology who, during the so-called Special Period crisis of the 90’s, authorized her minor children’s departure from Cuba. Her decision plunged her into a depression, which she tries to overcome by appealing to her religious beliefs of African origins, as evidenced by the hand of Orula on the bracelet she wears on her wrist. Tania’s debate centers on whether or not she acted correctly when she distanced herself from her children.

Eddy (Jorge Perugorría), manages some enterprise or “firm.” He is a cynic, a hedonist, an opportunist, a parasite, and he is unethical. He travels frequently, he “gets around by car,” constantly gets calls on his cell phone and arrives on the scene with two shopping bags and a bottle of whiskey, a real sign of his status. He is the living image of the great pretender.

Aldo (Pedro Julio Díaz), a character and a perfectly forgettable performance, serves as host for the meeting. He is a frustrated engineer dedicated to the crafting of batteries and just barely making a living, the reason his wife left him to leave the country with an Italian. He is the resigned, conciliatory type, and – together with his mother, with whom he still resides – is one of the plot’s most obvious clichés: a decent and nice Afro-Cuban living in poverty in Central Havana, in a promiscuous environment, surrounded by marginal individuals who sacrifice pigs on the roof terrace next door, of couples who argue loudly from their balcony and of good-natured neighbors who shout out the scores of the baseball game they are watching on TV.

His mother is the kindly black woman who gives good advice, with a scarf wrapped around her head, who makes the best black beans that everyone wants to eat, and who humbly sets the table before leaving the room. She is a shockingly dispensable character.

The cliché of drawings showing El Malecón, the harbor, the Plaza of the Revolution and the Capitol’s cupola are abundant, as silent evidence that the story takes place in Havana, which the same the scenery painted on cardboard could have validated. This almost forces one to remember – in contrast — the masterful way in which Fernando Pérez managed those icons of the Havana environs in his film Suite Havana, where, rather than mere scenes, they are co-stars conveying the spirit of the cityscapes.

What reasons did the commissioners have to censor this poor film during the last film festival in Havana?

Return to Ithaca exudes the oblique, patronizing and folk interpretation of a team of foreign filmmakers and, as such, it’s oblivious to the reality it that wants to present. Therefore, since they are ignorant of the intricacies of such a complex, varied, and nuanced community, the final result offers a superficial and plain view of that reality, unfolding, as a touch of local color, what actually constitutes yet another unfortunate stereotype.

In general, the plot clings to the past — which is really the only element all the characters have in common — by appealing to victimization, to catharsis and to forced conflicts between them, while the Cuban socio-political system, reflected primarily among the memories of the characters, is the invisible villain, the victimizer, flowing from each actor’s lines, though only in the third person, singular: “they sent us to agriculture,” they made us go to the harvest,” “they took us to pick tobacco in the countryside,” “they did not let us listen to The Beatles,” “they fucked up our lives,” and others along the same lines. A non-committal “they did such-and-such to us,” a kind of impersonal culprit entity which is, all at once, the system and nobody, and that allows sneaking the bundle out through the open escape hatch.

And, to put the icing on the cake, there is a version of Return to Ithaca, this calamitous cinematographic accident, that breaks both scenic as well as temporary and situational planes, so that, in some passages, the viewer witnesses a sudden and dramatically useless blackout on the roof, and immediately afterwards, as if by magic, the characters converse with a perfectly lit up Havana in the background, or a roof scene ends and — without a transition — the next scene takes place indoors, with the characters seated around a table in the dining room, savoring Aldo’s mother’s incomparable black beans.

If this disruptive intention was to surprise the viewer, it only serves to baffle him.

In short, when the parade of credits indicates that Return to Ithaca is over (at last!), the viewer can feel a strange mixture of relief and disappointment. Relief, because it will probably convince him that the most wasted 90 minutes of his life are just over. Disappointment, because, just like the very characters in the movie, he will feel deeply cheated. And so perhaps, as it happened to me, he will get up from his chair wondering what reasons the commissioners had to censor this poor film during the last film festival in Havana.

*Orula, a major Orisha in the Afro Cuban religion of Santería, (Yoruba in English), is the future prophet and the counselor of humans.

Translated by Norma Whiting