As a prank for the Day of the Innocents*, Alicia Alonso has ordered the National Ballet of Cuba, the same one as in The Man from Maisinicu, that Cuban film that not one of her young dancers has seen: “stab it, stab it …”

In this case it’s about stabbing a hanged corpse, one still kicking, of the Revolution and it’s imaginary forgotten. No one can be left out of the bestiality: everyone will have to embarrass themselves in public with their choreographic commitment.

And there is nothing better for this than dressing your entire company as if, instead of an aesthetic elite, they were obscene workers from the sixties. With the March of the Guerrilla, anachronistically interpreted by the choir of the Cuban Institute of Radio and Television (in olive green suits), Alicia Alonso made a mockery of everyone in the audience at the Grand Theater of Havana yesterday (with prices for foreigners ranging up 25 CUC ), in a supposed Tribute-Gala for the centenary of the conductor Enrique González Mántici.

Almost centenarian herself, this retro-revolucionary clown Alicia Alonso, recalls the one who starred ages ago, Rosita Fornes, in her UFO landing in Sports City (the same Rosita Fornes who today, Friday December 28, will go on stage at a concert, perhaps in memoriam to that capitalist prank for the Day of the Innocents).

It seems that barbarism in Cuba has mutated into nonsense, and that this will be the popular sign of our 21st century, in response to a the Realpolitik of a government increasingly less ideological but also less democratic, where the rights of citizens are already kidnapped in perpetuity behind the scenes of a transition of intrigue, blessed in its constitutional criminality in all the churches of this small island equally abandoned by the exile and by God.

Scaling the Sierra Maestra to sing opera without sound or pictures, wearing the boots of sugarcane workers instead of classic ballet shoes: the humor is a superb kitsch of these gestures that vainly try to hide the despotic power of more than a few international bank accounts. The dancers themselves chaotically chatted and cackled while pretending to march into a coda that might well title itself after that obsolete signature of the Ministry of Education: Comprehensive Military Readiness (PMI). I wonder how many of them, hilarious in their humiliation, have decided tonight to defect from their next foreign mission.

Then, as an epitaph, the woman who for decades saved a ballet shoe secretly buried under the floorboards appeared in the stage, as a gloomy talisman against the new generation of Cinderellas with pretensions of being a prima ballerina. The director of the local ballet and wanted to postpone as long as possible a future of freedom, where no one should be so godlike as to endow themselves with the archaeological title of Absoluta.

The worst, then, was the applause our island neo-bourgeoisie dedicated to Alicia Alonso, instead of sounding the trumpets of resistance, less rabid than ridiculous, at her institutional burial.

A sick joke, like Fidel Castro’s moringa** manifesto, or the rheumatic immigration reform his younger brother, the truth is that I left the García Lorca Room wanting to hang myself, preferably from a guazuma (bay cedar) or caguairán (a tropical hardwood): “stab me, stab me,” I would tell the transhistoric thugs of this Cuban atrocity.

They can now stick their sharp daggers up to the hilt in our throats. I promise them that no totalitarian tracheotomy, be it legal or mafiosa, is going to invalidate or vacate the truth that is already innocently incubated in our voices. Let it be, then, that this December 28 is the perfect date to announce the joke that there is no military mummy that lasts a hundred years nor a ballet troop that resists it.

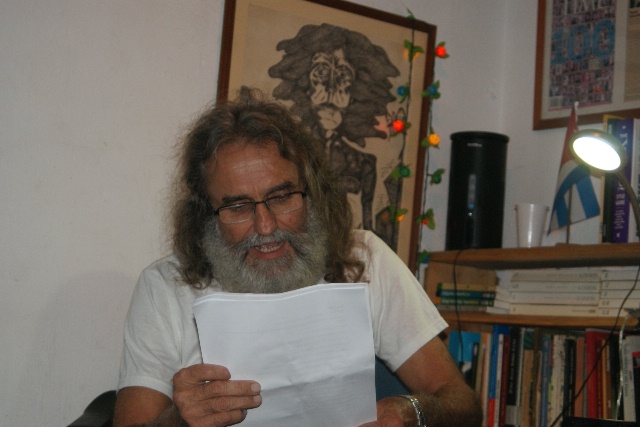

Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Translator’s notes:

* December 28, the day Herod had the male children of Bethlehem massacred.

** Moringa is a kind of tree. In one of his last public utterances Fidel Castro announced that Cuba would meet all its needs — including for meat and milk — from moringa.

Translated from Diario de Cuba.

December 28 2012