A New Failure / Fernando Damaso

The announced rescue of sugar production, after the ravages of the Alvaro Reynoso Task that finished dozens of plants, and the adjustments and readjustments of the “upgrade” and the application of the “guidelines”, seems not to have achieved the objectives, with production having, in some cases, declined.

Despite nearly six months of harvesting, it appears that we not exceed the one million four hundred thousand tons of sugar expected (an extended time when historically, with less technological equipment and development, the harvest reached four to five million tons in less than ninety days).

At least, that is what emerges from the literature on the harvest in the province of Villa Clara. Figures are figures: despite organizational measures taken, resources allocated, etc., the harvest produced 11,000 fewer tons than planned (5,400 tons more than the previous harvest, which was 5,600). In addition, it missed the 44% of the time (26.66% is attributed to the rains), the sugar mill capacity reached 56%, a very low indicator, and industrial performance was 10.60.

The listed causes are many: lack of control, lack of coordination and forecasting, rainfall, human activity, especially among those cadres led the process, administrative and technological indiscipline, excessive foreign matter, grinding cane backward and burnt, low combined productivity, lack of on time completion with the necessary means to guarantee the results, indiscipline among the brigades at the beginning and end of the day, poor quality of delivered equipment and parts, late delivery to the centers (up to 37 days overdue), and so on. The list of misfortunes could go on and become endless. A similar picture is repeated in other provinces.

I ask two simple questions: Is this not enough, repeated year after year, to finally understand that the “model” does not work? Why do we have to wait before deciding to discard and replace it with one that has shown itself, despite its imperfections, to be better, more productive and better?

7 June 2013

Yurisdislaidis’ Fifteenth Birthday / Rebeca Monzo

After a disastrous first marriage which bore no “fruits,” Isabel — a slim, young brunette — met a young laborer with whom she fell hopelessly in love. They decided to become a couple almost on the first date. From this “explosive union” a child was born, whom they named Yurisdislaidis because compound names and those with the letter Y were very fashionable at that time.

All her life Isabel had dreamed of having a daughter whom she could “dress up” and shower with affection. After giving birth, she firmly resolved to stash away part of the money she earned as an at-home manicurist in a clay jar that had belonged to her grandmother. She left it in the care of her mother, who did not trust banks. Every week Isabel fattened the jar, depositing part of her earnings in it.

Meanwhile, her selfless husband was using the old Oldsmobile he had inherited from his father as a taxi. He was taking his chances, doing it “on the side,” since he was never able to obtain a license. By redoubling his efforts, he drove more routes than his malnourished body could stand, all in the hopes of bringing home some extra money so that his wife would not have to work so hard or “touch her little savings account.”

They made these sacrifices and many others perhaps not worth mentioning, including foregoing the eighty grams of daily bread allotted to each member of a nuclear family in the ration book, which they gave to the little girl. She got one for breakfast, another for her school snack — filled or topped with whatever they could get their hands on at any given moment — and another to accompany a café con leche which she had before going to bed. This is how Yurisdislaidis grew up, eventually becoming a lovely young lady.

There was still a year to go before the her fifteenth birthday, and the family had already put together a trousseau for the much anticipated celebration. They still had to find a suitable pair of shoes for the occasion, a make-up artist and a photographer.

It was then that Demesio, the father of Yuris — curiously, this is what he called the child, perhaps because it was too much effort even for them to call her by her full name — began working as a mechanic, fixing his neighbors’ broken cars. It was a skill he had learned the hard way over many years by fixing his own car after driving it through Havana’s pothole-filled streets and avenues. All this caused his health to deteriorate, making him look older than he really was.

Isabel’s eyes fill with tears as she describes the unforgettable day in which her beloved husband arrived home exhausted but joyful, “with a smile from ear to ear” and his face glowing with emotion. He was carrying a package in his arms which he laid at her feet as though it were an offering to a goddess. It was a brand-new pair of white shoes with high heels and two shiny buckles as the only ornamentation. A regular client, who was aware of his troubles, had provided them as a gift for his daughter. Now she only needed to find a modern photographer with good taste since she was already getting the make-up artist — a charming gay man, who was the brother of one of her clients — for free. Everything “was set!”

Finally, the long-awaited day arrived. The local Committee for the Defense of the Revolution and the neighbors on the block were all excited, watching the comings and goings of strangers entering and leaving Isabel’s house. It was a big event. From the early morning hours music blared at full volume, alternating with the voices those present, screaming to be heard. These were the friends who had come to clean and decorate the house. In the main room there was still the portrait of the former lady of the house, as always with flowers, who had the foresight to will the place to Isabel, her former employee, legally leaving it to her as an act of gratitude for having been her companion and caregiver after her entire family had decided to leave the country. She had stayed behind because she wanted to die in Cuba.

The first to arrive that day was Francisco, the make-up artist, followed by the lady who was providing the various outfits for the photo shoot. When the birthday girl was finally ready, the young photographer arrived. A stunning 1950s convertible belonging to one of her father’s friends was parked in front of the house, waiting to drive Yurisdislaidis to the Plaza de San Francisco in front of the Chamber of Commerce building. She was dressed in a distinctive costume like those from the Cuban soap opera, Las Huérfanas de la Obra Pía — with parasol and all the other 19th century accessories — to have her picture taken among the pigeons and recently restored historical buildings. Behind Yuris was an entire entourage, darting to the various locations chosen by the photographer. They were the make-up guy, the costume lady, the camera man with his tripod slung over his shoulder and her mother carrying baskets filled with artificial flowers, shoes on loan, wigs of one sort or another, and head ornaments for her beloved daughter.

After returning home, a few “more artistic” photos were taken. These showed her peeking from behind a shower curtain, exposing a bare thigh, pretending to fall down head first with her legs strategically placed above her, coming down the stairway, carrying a hat and suitcase as though she were on a trip, and so forth. These were to fill an album which she would later proudly show to relatives, friends and teachers at her school.

From what I was able to find out later from some neighbors, the party was “over the top.” Beer and rum flowed freely. There were fish croquettes, pastry hors d’oeuvres, cold macaroni salad and guayaba tartlettes, all provided by some friends. Afterwards, they served a big pink cake decorated with flowers and fifteen candles — the kind that do not go out when you blow them — procured by someone who “had come from far away.” The extravaganza ended at dawn, when there was nothing left to eat or drink. To this day people in the neighborhood still talk about it.

Only a couple of years later I happened to run into Isabel, noticing how much older and thinner she looked that usual. When I asked about Yuris, she made an attempt to smile. “She’s fine,” said Isabel, “but she wants to quit school because she says she does not feel motivated. So I am still struggling, trying to fill up the clay jar again. My daughter has now gotten it into her head that she has to be made a saint!”*

*Translator’s note: Kari Ocha, or “to be made a saint,” is an initiation ritual of Santería, an Afro-Cuban religion, and can cost as much as $800 if you are Cuban, and significantly more if you are from overseas.

6 June 2013

Porno Para Ricardo Can Tour Europe if YOU Help! / Gorki Aguila, Ciro Diaz

For the handy little DONATE BUTTON <-- Click there! 6 January 2013

Chronicle of a Brief Trip / Miriam Celaya

I’ve just returned from a short trip to Stockholm, Sweden, where I was invited by the government of that country to participate in the Stockholm Internet Forum, Internet Freedom for Global Development, which met on May 22nd and 23rd. While there, I had the opportunity to meet up with other Cuban activists living on the Island, with whom I participated on a Cuba seminar that took place at the Swedish Parliament, and a panel on freedom of the press in Latin America, at the press room attached to the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Neither one of these activities were related to the event program.

In just a few days in Stockholm we visited a local newspaper, the headquarters of Reporters without Borders, the offices of ECPAT, a nongovernmental organization fighting against child prostitution and pornography and the trafficking of children, and the headquarters of The Civil Rights Defender. We were also invited to the launching of the book We Must Take the Police Out of Our Heads, edited by the International Liberal Swedish Center, a report on the Island’s reality between 1998 and 2012 and the peaceful struggle for democracy, from the perspective of the analyst Erik Jennische.

Of course, I managed to walk around and learn something about the city, its people and places.

Some regular readers have written to me, asking me to comment on this blog what I consider my most important impressions in this experience, and how they could be used in the struggle for rights in Cuba. Personally, I was pleasantly impressed with the reception of Cubans who manage the magazine Misceláneas de Cuba, headquartered in Sweden, with whom we had the privilege of sharing through various meetings they set up for us, and I also met others whom I knew only through the mail up to then (as in the case of Hugo Landa) and the dozens of Cuban residents there and in other European countries that showed extraordinary solidarity with our Cuban struggle. Verifying the bonds that unite Cubans of all points of the diaspora is a source of inspiration and hope in the midst of the totalitarian drought in which we live.

On the other hand, the event’s sessions highlighted the technological backwardness and computer weakness in Cuba. In addition, many of the delegates expressed their solidarity with the cause of freedom of expression, information and news that Cubans are demanding. Some work strategies of various organizations and institutions in Sweden could be useful in the Cuban case, and we established links with them to implement proper agendas, in accordance with our reality.

A few yeomen of the guard were present among participants of this area, questioning our right to demand freedom when “Cubans have guaranteed free health care and education”. I will not repeat our answer to them, but suffice it to say that we did not see them again, nor did they try to boycott our public presentations, for their own good.

To those who have been so concerned about the funding of this trip, I will personally answer, not because they deserve it, but for the sake of transparency. I was invited by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Swedish government, which generously assumed all costs for travel, accommodation and food. I take this opportunity to publicly thank from this space the many attentions received from all Swedish organizations I had contact with, and in particular said Ministry.

Finally, I hope that, in future editions of this Forum, Cuban participants will have the opportunity to tell a different reality than we have at present. As for me, I will continue to do everything possible to contribute to make it so.

31 May 2013

Debating Social Networks / Luis Felipe Rojas, Alexis Romay

I asked several cyberactivists their opinions about the social network Facebook, about its impact on the island and the relation it’s created, within the island, outside the island, with Cubans and the insults from Power.

Alexis Romay, a good man, partner and friend, sent me (after-hours) this response and was kind enough to include it on his personal blog Belascoaín y Neptuno. Many thanks to him, and to the friends who joined in the debate, thank you as well.

Totalitarianism in the times of social networks

By Alexis Romay

Cuban poet and activist Luis Felipe Rojas, author of the blog Crossing the Barbed Wire, is doing a survey on cyberactivism and, by the way, sent me a question. Here goes, followed by my response.

How do you think social networks like Facebook — with many detractors who see it as puerile — are helping the community of activists on the island?

In a totalitarian regime like Cuba, social activism beyond the margins of Power has a very high cost which started with the automatic conversion of these activists into “dissidents,” which implies a dangerous and immediate association of the term with this aberration of all nationalisms: the dissident is a traitor to the fatherland. We can’t forget that in the name of love, mother, fatherland with a capital F, the worst atrocities are committed.

This isolation of the activists, converted by state decree into dissidents, passes through dehumanization (they are then transformed into “worms” by similar abracadabra), slides down the scale to social stoning and may end in physical death.

In other words, the “worm,” before being one, was a dissident, social activist, citizen, and in the beginning, a person. I put the steps in order to illustrate the precipitous drop on this scale in which the nonconformist Cuban — or person in any other totalitarianism — begins his journey as a human being and ends it in the order of invertebrates.

I give this preamble to highlight the pariah status that opposition in Cuba leads to. In the face of this forced isolation to which Cuban activists are subjected, social networks, not just Facebook, become the human tissue that envelops them. To feel the support of a virtual community has a specific weight for anyone who has been separated, by imperial edicts, from the society to which they belong. But in addition to filling this gap, social networks also serve as a protective shield for activists; they make the impunity of the regime ever more costly for it at the international level; they remind the Castros that the vast dungeon they have made of Cuba has glass walls and it is already impossible for them to hide their repressive methods.

If the political police evict a family of opponents, deal out a beating, or effect an arbitrary arrest at eleven in the morning, five minutes later the information will be circulating on the networks with hashtags that tarnish this great achievement of the regime of the island which is projecting an image of itself that does not correspond with its totalitarian reality.

In fact, Castro has a huge presence in the networks, the budget allocated for this purpose must be incalculable. As Cuban Democrats we can and should establish a presence on the networks with an infinitely more appealing discourse, creating and disseminating our own spaces. This will be the testing and projection in the digital world of that democratic country we dream of.

5 June 2013

BREAKING THE INNER-CIA / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Speaking of Freeing People… / Rolando Pulido

Entrance Exams: An Assessment of Education in Cuba / Yoani Sanchez

They’re no longer dressed in blue uniforms and some boys even show off their rebellious manes. Hair that no teacher will demand they cut — at least for the next few weeks — hair that will ultimately fall to the razor of Obligatory Military Service. They still look like students, but very soon many of them will be marching with rifles slung over their shoulders. They are young men who just, days ago, finished their school days at different high schools all over Cuba. The college entrance exams are long past and this week they’ve learned who will have a place in higher education.

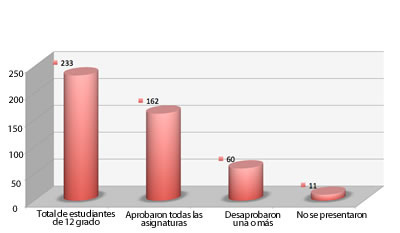

Just outside the schools, the lists of the accepted and unaccepted speak for themselves. José Miguel Pérez High school — in the Plaza of the Revolution municipality — could be a good example to explain the situation. This educational center is one of the best performing high schools in the capital. A situation partly due to the professional and economic composition of the neighborhood, which means many parents can afford after-school tutors (we refer to these as “dishtowels” — they clean things up). Despite these advantages, the end-of-year statistics for this school are more alarming than satisfying.

Of 233 12th grade students in this high school, 222 took the entrance exams and only 162 managed to pass all tests. The rest will have to go to a second round, or content themselves with failure. The highest number of low marks was in Math, in which only 51 students achieved a score of between 90 and 100 points. In the applications for careers, teaching specialties are repeatedly put down as a back-up choice; “To guarantee getting a place, even if the tests don’t go well,” these potential teachers of tomorrow say, with a certain indecency.

Statistics from José Miguel Pérez High School

The beginning and end (?) of a mistake

The young people who completed secondary school this year are the products of the educational experiments led off by the so-called Battle of Ideas. They are 17 and 18 today, so they started junior high as the “Emergent Teachers” program was gaining strength, a program that put hastily trained young people barely out of their teens — if that — at the front of the classroom. Today’s graduates were educated in classrooms where television and VCRs were the protagonists, for lack of sufficiently trained teachers. At the most difficult times they could count on receiving at least 60% of their classes from a screen. They also went through puberty at a time of rising ideological indoctrination. While it is true that this has always been inherent in teaching in Cuba over the past five decades in, its climax came after the Elian Gonzalez case. Fidel Castro took advantage of that event in the late nineties to impart a twist to the political discourse in all aspects of national life.

Those who graduated from the twelfth grade a few weeks ag, are the first batch who did not have to go to boarding schools in the countryside. Encouraging news for the young people themselves and especially for their parents. However, the readjustment for teachers caused by the change forced many of them to rethink careers based on study, books and binders. The teachers who came from these schools in the countryside had to adapt to new conditions. Despite the difficulties of the former regime of internment, for the teachers these countryside schools were sites of direct contact with the farmers who sold or traded for agricultural products. One of the few incentives for working in such a place was being able to take some bananas, taro, pork or fruit to the city at a much cheaper price than in the markets of Havana. The loss of that little privilege discouraged some teachers from continuing on the path of teaching.

Memorize or question?

The countless hours lost in the classroom to teacher absenteeism is another of the hallmarks of recent graduates. To this we have to add the decline of the investigative character of science instruction, due to the deterioration or absence of chemistry, physics and biology labs. In many high schools chemistry experiments were practically canceled due to the shortages and fear that students would have access to the chemicals. Physical education, computer science and English were the biggest losers in the exodus of teachers to other areas of employment. High school education emphasized rote learning of dates, names, events, without progress in creating their own opinions, a spirit of asking questions, or the capacity of discernment. Graduates can hold in their heads the years and important days of our country’s history, but fail to form their own opinion about what it all means.

The quality of handwriting, spelling and the correct use of Spanish also fell short as educational objectives. This coming September, university classrooms will see students with serious deficiencies in all three areas. But that does not mean that they will be faced with excessive demands or be unable to complete their programs of study. They will attend a University whose quality of teaching is far from that once exhibited in Cuba. In the 2013 ranking of Latin American universities, the University of Havana fell from position 54 to 81, another sign pointing to the urgent need to review the entire educational model. The educational level of the new entrants to higher education, has forced them to lower the bar.

The tinkering with the alchemy of learning, the successive experiments marked more by the voluntarism than scientific analysis, the excessive presence of ideology in every subject, the encouragement of docile, rather than questioning, minds, students’ limited access to updated materials (read internet) and the educational fraud that flourishes where ethics is absent, are all undermining one of the main pillars of national identity: that which consists of knowledge, academics and teaching. But a problem can not be remedied unless we confess that it exists. So while they continue speaking in a triumphalist tone about Cuban education, it will continue to sink into mediocrity, into material and pedagogical deterioration.

6 June 2013

Weekend News / Fernando Damaso

Without any hint of shame the state-run press reports that an American citizen attending a public presentation by her president at the National Defense University interrupted him and even questioned some of his policies in a rude manner according to several journalists present. The importance of this news for Cubans lies in the fact that this woman, as well as many other people in the United States and other democratic countries, have the right to do this. In our country on the other hand, not only would it be considered a serious action, you could also spend years in jail for it.

Without any hint of shame the state-run press reports that an American citizen attending a public presentation by her president at the National Defense University interrupted him and even questioned some of his policies in a rude manner according to several journalists present. The importance of this news for Cubans lies in the fact that this woman, as well as many other people in the United States and other democratic countries, have the right to do this. In our country on the other hand, not only would it be considered a serious action, you could also spend years in jail for it.

In another article it is reported that, in a session at the Ninth Congress of the Union of Cuban Journalists, someone posed the question, “What sort of journalism does Cuban socialism require to make it stronger as it goes through a period of change?” The replies all have a common denominator: to petition the state to act less as a guardian and to request authorization to be more critical, though always “being aware of the challenges that the country faces in the midst of the incessant and worsening harassment by the American government, which has not abandoned its goal of destroying the country’s socialist project…,” blah, blah, blah. Without the least embarrassment these journalists accept state control over what they write and report, and their appeal amounts only to “being allowed to write and report a little more.” It was always my understanding that rights are not something to be begged for, but rather to be demanded.

Another article mentions a “big tweet for Cuba” (a reference to the Five*, who by now, if my math is correct, are four), accompanied by a photo of a “stand in” at the front of the White House. As I indicated at the beginning of my post, how wonderful to be able to do all this freely, without anyone interfering! It is as safe and secure as a picnic. In democratic countries, that is, because if these things happened in ours, they would all be considered “destabilizing actions orchestrated by local mercenaries fulfilling orders from the empire.” That simple.

It is striking that presumably intelligent people would lend themselves to this sordid political game by participating in it as though they were performing a commendable action for which they deserve respect and even applause. I believe the solution to the problems between the governments of Cuba and the United States (and I say governments) must be through dialogue. I do not believe it can be achieved through tortuous paths, but through truth, honesty and frankness, assuming each lives up to its responsibilities.

*Translator’s note: Five Cubans serving prison sentences in the United States for espionage, for whose release the Cuban government has been actively and publicly campaigning. One of the four has been paroled and recently returned to live in Cuba with the permission of the American courts, in exchange for giving up his U.S. citizenship.

3 June 2013

Prison Diary XXIV. Cuba and Its Politics of Minions / Angel Santiesteban

Once again, the Cuban regime supports — far from international view — the dictatorship ruling Syria. We are always on the same embarrassing team: Russia, with the dictatorship of Putin; China, more of the same but with different style; Bolivia, where its president just manipulated the Constitution to guarantee himself a place in the upcoming election for a third term; Nicaragua, few presidents have such effrontery; and why continue, their names speak for themselves: Ecuador, Venezuela, Iran, and as if that wasn’t enough, North Korea.

And the news, in the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba on May 16 the headline encapsulates with apparent what is nothing more than a disgrace: “A dozen countries oppose UN resolution on Syria.” That is, the news is not that 107 countries approved it, or even that 59 abstained, including Brazil, one of our allies.

As much as we should be accustomed to this arbitrary politics of benefit to party members, in the style of highway robbers, and of course, its obsession with confronting the United States, simply leaves us outraged.

In the face of this arbitrariness typical of the Castros, I can’t stop being ashamed; the only thing that saves me is my opposition to the government and it’s national and international politics.

Ángel Santiesteban-Prats

Prison 1580, May 2013

5 June 2013

Narcisolpl / Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo

Loose in Havana, Gandalf and Elton John / Yoani Sanchez

The Poster for British Week in Havana

London has come to Havana. During this week of British Culture that is celebrated from the first of June in our country, even the climate has decided to be in sync with that of the other Island. Grey skies, drizzle, mist at dawn. All we lack is the silhouette of Sherlock Holmes sneaking around a corner or a magician knocking with this staff on the wood of our door. They are days of great music and a chance to appreciate unusual schedule in the movie theaters. Since last Tuesday they have been showing a selection that includes the 2013 Oscar winning documentary Searching for Sugar Man, and also the biographical film Marley, about the life of the famous reggae singer and composer. The selection of cartoons for kids and teens will probably attract a good audience at a time when many are on vacation from school.

I have been enjoying some of the programming not only for me but also for many others. Especially thinking about those young Cubans , or forty years ago, secretly listened to an English quartet which the official media now play everywhere. The striking colors and the design of the poster for this “British Week” has evoked for me the iconography of the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland, and also the delightful adventurers in the Yellow Submarine. So some of us have also taken it as a tribute to those battered Beatlemaniacs from back then. These days, however, the greatest comfort comes from the window cracked open to let in this fresh air that comes to us from the outside. This gift of sensing that culture can make the Atlantic seem narrower, the passing years shorter, the losses recoverable.

5 June 2013

The Long Arm of Censorship / Miguel Iturria Savon

From May 29th until today I could not open VocesCubanas.com, the alternative platform that contains my blog Island Anchor. As I thought the “closure” could be only be in the Spanish Levante — I live in the province of Castellón, in the community of Valencia — I called followers of my posts living in Zaragoza, Madrid, Canary Islands, but none could access “Cuban Voices” nor enter my blog, not even from Google by searching on the titles of the last texts.

From May 29th until today I could not open VocesCubanas.com, the alternative platform that contains my blog Island Anchor. As I thought the “closure” could be only be in the Spanish Levante — I live in the province of Castellón, in the community of Valencia — I called followers of my posts living in Zaragoza, Madrid, Canary Islands, but none could access “Cuban Voices” nor enter my blog, not even from Google by searching on the titles of the last texts.

Coincidentally, Wednesday May 29 was the last day of Yoani Sanchez’s stay in Madrid, where she delivered a speech at the ceremony for the Ortega and Gasett awards, given by the newspaper El Pais; the next day she was received in Havana by family and friends while the Spanish newspaper reproduced her words and pictures with former President Felipe González and other figures of the Spanish Socialist Worker’s Party (PSOE) and the media.

No one should be ready to think that the closure of the Voces Cubanas portal in Spain was a way to lessen the impact of her words and to annul any commentary on her extensive tour of Americanand European countries. But who benefits from the silence of censorship? Who gave the order to disconnect? Where and by whom was it executed? The answer points to the officials who monitor the news in the Cuba Embassy in Madrid and to the Island regime’s network of consulates in the Iberian Peninsula.

It is not the classical theory of conspiracy; the Castro regime tactic is very old and the order stands, the diplomats-cum-State-Security-Agents executed it based on a Guide to events that demystifies the Havana government’s propaganda. They simply overload the networks, hack pages, multiply the trash emails against some, and “take the offensive” against others, even in media such as El Pais. The rest is up to time and the naive who are silent before the long arm of censorship.

4 June 2013

Emigration / Cuban Law Association, Noel Rodriguez Ávila

From an economic point of view Cubans have come to feel that they lack a future, it has been more than five decades and they have seen no fruits of their labors, which don’t even meet their basic needs of housing, food, clothing and a job with a decent wage.

The loss of motivation to study careers requiring a technical or university education comes from there being no economic advantage, nor even jobs to fill with these qualifications. The insecurity makes people look to the future and old age with fear.

There is no hope of prosperity. Every discourse has a political focus, with regards to the economy they only talk about working and being productive, about control and demands, not of new factories or investments or more employees. They talk about a primitive agriculture, subsistence level. An educated people can’t accept these miserable proposals.

Religious freedom is tolerated, but the system doesn’t like it. There is a lack of freedom of expression.

Cuban people are taught to watch each other, there’s a paranoia about being heard and being informed on to the authorities.

The State’s organizational structure is designed to convince us that all is well, or to understand what is wrong by looking for external causes, or in lower level management and not at the strategy of the higher ups who re never wrong. This limits the possibility of changes, all this is integrated into every Cuban citizen leading to a frustrated frustrated, hopeless personality, faking it, with no exit, looking abroad for an option, a hope.

The aspiration of every professional is to go on an international mission to earn a little money, have a house, buy a car, and have some comforts; when they can’t achieve it they want to leave even more to get away from their family, their country.

Emigration to the United States has also been an option, although risky, sad and cruel, when people use any kind of floating artifact to get to that country, to embrace a hope for prosperity and to help their family who with anguished hope said the magic words, “arrive safely” and then, gratefully, receive remittances that alleviate their economic stress.

In any event, the solution for Cubans is not outside, but within.

5 June 2013