Morgan Freeman was at the finals. Seated in the VIP section of Soccer City with his dark baseball cap and a nervous expression on his face. Nervous in the angle the television offered us, of course. Perhaps two seconds later he would’ve been euphorically screaming if he rooted for Spain or would have been another disappointed one if he rooted for Holland.

Morgan Freeman was at the finals. Seated in the VIP section of Soccer City with his dark baseball cap and a nervous expression on his face. Nervous in the angle the television offered us, of course. Perhaps two seconds later he would’ve been euphorically screaming if he rooted for Spain or would have been another disappointed one if he rooted for Holland.

But the truth is, he was there. Just as during this month of the World Cup, many passed through the fields of South Africa (citing only a few) musicians like Mick Jagger and Shakira, actors Leonardo Di Caprio and Charlize Theron (back to her native land); tennis player Rafael Nadal and top model Naomi Campbell; the prince and princess of Holland and the king and queen of Spain, ex-president Bill Clinton and a long et cetera of chief executives, artists and business men and women from all over the globe forced by soccer to take a few days vacation on the poorest of all continents.

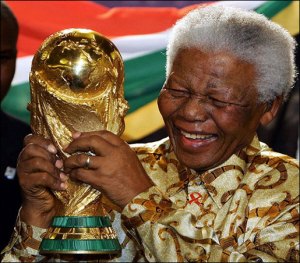

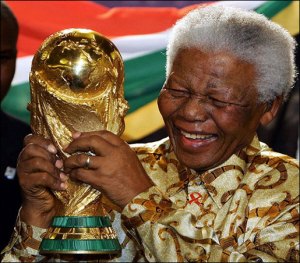

However, few other figures, I think, represent the sweet and festive reality that it is to contemplate the magisterial Morgan Freeman enjoying the finals just like another one of the 90 thousand spectators who filled up the Soccer City of Johannesburg this past July 11.

Why? Well because fewer than twenty years ago, these fields would have been open to Mick Jagger or the beautiful Charlize Theron, but probably not for him. Not for a “segregatable black” who, before 1994, had his own place on the beach, his own section of the sidewalk, but not a theater box seat inside a stadium for the white ruling class.

That is why I believe that two countries have just enrolled themselves in Modern History with this World Cup. One, the champion. The other one, the host. The rest is just color and enjoyment, anecdotes and effort. But these two countries have just given the world a lesson so subtle yet so overwhelming: Blessed be prosperity, blessed be evolution with which over the years two nations with very deplorable pasts have experimented.

First, Spain. The same Spain where today’s heroes are not Generals nor advanced plenipotentiaries, who do not achieve their fame by scorching caciques in the bonfire but by playing with a foot ball and, who can doubt it, exposing a fellowship and beauty over the field like only the best Selection of the moment can. It is a remarkable irony that champions are crowned, for the first time in ninety years, right on a continent where centuries ago it drained its own life’s blood with its shipment of slaves to the new world to slake its thirst for metals and power.

Are we speaking about the same Spain? No, definitely not. Not about the Spain of Torquemada and its infernal Inquisition. Nor is it the one of General Francisco Franco, whose bones I dare say shudder with shame before the face of the country which during decades he tyrannized.

This is the democratic Spain that in only a few decades reached the dream of all countries gripped by dictatorships: overcoming not only its economic indigence, but also its spiritual. Raising the collective spirit of the nation until it was more prosperous, more free, more hopeful for all its people. A country that only twenty years ago still exported Spaniards to all parts of the orb in search of peace and prosperity, and that today, must regulate immigration in order to preserve economic and social stability.

Is this motherland to Hispanics the Earthly Paradise? Of course not. Is it free of unemployment, crisis, internal ethnic conflicts, or terrorist organizations and suicidal attempts? Nor that. But not knowing the progress of this Spain that nowadays celebrates thanks to the most universal of all sports, comparing it with the one of only a handful of years ago, not only is it stubborn statistics but political blindness.

We still have South Africa.

If anybody, after knowing its designation as the site of the most watched sporting event of the planet (according to official figures, it has twice the television audience of the Olympics), grinned with disbelief and disapproval, I am sure they slyly hide it today. I include myself.

After going through some cultural and economic powers like France, Korea-Japan, and Germany, landing the World Cup in a continent destroyed by illnesses, violence and severe poverty, I thought it, from FIFA’s part, a decision if not quite sensible, doubtfully a romantic one.

Thankfully, I was wrong. Because South Africa’s World Cup has not only been the most beautiful culturally speaking, overflowing in musical and dancing references, and where natives clearly reminded us that from these latitudes is where, we, human beings, took our first steps on the planet; not only has it been a World Cup of truce during the crisis and the political idleness of the moment, but South Africans organized a feast as (or more) showy and technological than those held before in the hands of stronger powers.

Again the word evolution: the million dollar soccer date has just concluded in the same country that in 1964 incarcerated Nelson Mandela on Robben Island for twenty-eight years. In the same country where racist excess from Apartheid segregated 80 percent of the black population, and segregated a whole country in an international isolation whose economic consequences would lead the government to declare South Africa, in 1985, in state of emergency due to a loss of value of the Rand, the official currency.

The selection of this site over Morocco, the other great candidate to organize the event in the Black Continent, was deeply influenced by the favorable economic perspective that the nation has experienced in the last years, generating one of the highest standards of living on the continent, thanks, in part, to the return of the foreign investments which practically vanished during Apartheid due to international sanctions.

Another important factor (and vital to my judgment so I can comprehend the qualitative jump in South Africa in less than two decades of democracy), was the significant reduction in its crime statistics.

Yes, the same State where, in 1976, the police responded with bullets to the rocks of the students in the schools of Soweto, and massacred some 566 children in disturbances that shocked the International Community, today offered its millions of visitors more security that the majority of its companions on the continent.

I am sure: not because there was an exciting World Cup, the unjust differences between the lifestyles of wide sectors of the population will be gone from South Africa. Not because David Villa or Diego Forlan have led a tournament of dreams, the acts of violence that have marked a continent over and over again subjugating men and History, will disappear from Mandela’s country.

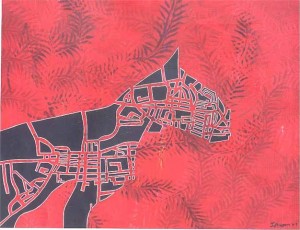

However, I don’t doubt that after the World Cup of the jumping Jabulani and the stentorian vuvuzelas, the leopard Zakumi, the visionary octopus Paul; the Cup that broke through superstition and (as an example) crowned for the first time a team that had reached the finals with one defeat among all seven games; after this experience of universal reach, I am sure that all of the African nation will look itself in the mirror of the present as the best antidote against a past that it should never look back to, ever. I am also sure, that full of national joy in the Spanish Motherland, fewer murderers, fewer thieves, fewer suicides and fewer extortionists will show up on the streets in coming days to perform their fearful acts, and that Spaniards will all feel a pride that grows out of a football but, bleeding from civil wars and sunk in a Jurassic military dictatorship, they wouldn’t have been able to celebrate with all this pride in previous decades. Even for as long as Andres Iniesta would have sent la Jo’bulani to the depth of the nets.

I believe that just for the speed with which these two countries distanced themselves from their pasts of intolerance and exclusion, it was all well worth it.

Of course, also because hundreds of blacks, and a “crack” from the world of acting like Morgan Freeman, experienced the finals in the Soccer City of Johannesburg with the sole concern of whether or not their team will take the gold Cup in their hands.

Translated by: Angelica Betancourt

“Don’t believe, don’t fear, don’t beg.”

“Don’t believe, don’t fear, don’t beg.”

In 1833, when Havana was ravaged by cholera and there was a shortage of doctors, a boy of 13, immersed in the care of the sick, discovered his true vocation. When asked by one San Juan de Dios friars who observed him with curiosity whether he would like to serve God by caring for the sick, he answered, “Yes, Father, it is my greatest dream.” Almost immediately he took his vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and became part of the Brothers of St. John of God, a hospital order which had representatives in Cuba from 1603. This child who become a monk, and who had been placed by his parents a month after his birth in the Real Casa Cuna of St. Joseph the Patriarch, was Brother Olallo José Valdés.

In 1833, when Havana was ravaged by cholera and there was a shortage of doctors, a boy of 13, immersed in the care of the sick, discovered his true vocation. When asked by one San Juan de Dios friars who observed him with curiosity whether he would like to serve God by caring for the sick, he answered, “Yes, Father, it is my greatest dream.” Almost immediately he took his vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and became part of the Brothers of St. John of God, a hospital order which had representatives in Cuba from 1603. This child who become a monk, and who had been placed by his parents a month after his birth in the Real Casa Cuna of St. Joseph the Patriarch, was Brother Olallo José Valdés.

After sorting through various possibilities, the Spanish journalist Lali Kazas and I agreed to rent a car and head to Ciego de Avila.

After sorting through various possibilities, the Spanish journalist Lali Kazas and I agreed to rent a car and head to Ciego de Avila.

Morgan Freeman was at the finals. Seated in the VIP section of Soccer City with his dark baseball cap and a nervous expression on his face. Nervous in the angle the television offered us, of course. Perhaps two seconds later he would’ve been euphorically screaming if he rooted for Spain or would have been another disappointed one if he rooted for Holland.

Morgan Freeman was at the finals. Seated in the VIP section of Soccer City with his dark baseball cap and a nervous expression on his face. Nervous in the angle the television offered us, of course. Perhaps two seconds later he would’ve been euphorically screaming if he rooted for Spain or would have been another disappointed one if he rooted for Holland. Exactly how do minors become affiliated with the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution?

Exactly how do minors become affiliated with the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution? However, I can assure you that less than 1% of the members of the CDR know the rules of the organization. The important thing is your commitment, not what you are committing to. They don’t care if you consent to the rules, nor if you comply with the obligations assumed.

However, I can assure you that less than 1% of the members of the CDR know the rules of the organization. The important thing is your commitment, not what you are committing to. They don’t care if you consent to the rules, nor if you comply with the obligations assumed.