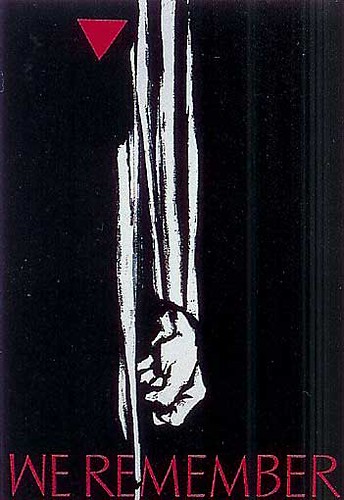

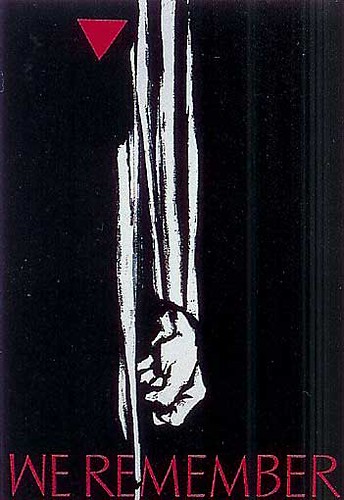

In 2003, 75 Cubans were arrested in four days. Their crime? Being pro-democracy political activists, fighters for human rights, or simply journalists independent of the hegemonic line of the only Cuban political party, the Communists. Pedro Argüelles Morán was one of them.

Seven years later — in the same arbitrary way as the imprisonments — we learned through a communication from the Cuban Catholic Church that the government had agreed to free them within — an unfair paradox — four months.

This November 7, the long period the Cuban government allowed itself to restore freedom to these innocents expired, and we are faced with a sad certainty: of the 75, the only ones who have been released are those who agreed to accept a painful condition: exile. Of those who dream of returning to their homes, only one is in his house. The eleven remaining in prison are witnesses to the dripping of a lie, the unfulfilled promise of a government that does not keep its word.

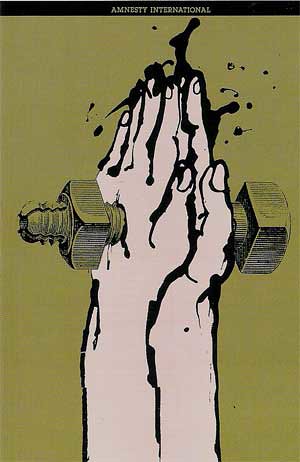

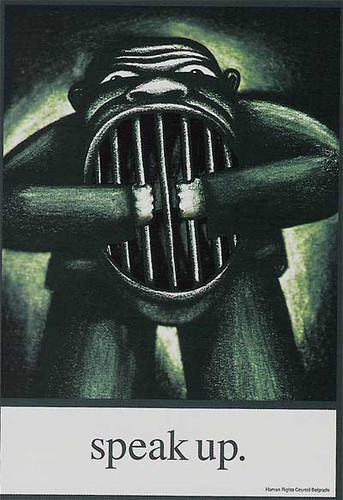

1 – Pedro, you are sixty-two years old, you have spent seven years in prison and been sentenced to twenty. The Cuban government agreed to release you but did not keep its word. You are recognized as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International, and you are one of the independent journalists who wants to live in Cuba and you demand to leave your cell for your home. Tell me what you did in 2003 before being arrested.

I would like to correct an error: I have been a prisoner for seven years, eight months and two days. I practiced as a freelance journalist in the province of Ciego de Avila. We had a tiny new agency, “The Avila Independent Journalists Cooperative” (CAPI). And we were several brothers: Pablo Pacheco Ávila, my friend and companion; Oscar Ayala Muñoz, from Morón, a tremendous person, economist, professor of economics at the University of Ciego de Avila, and some other brothers.

We tried to write about reality, we denounced the Human Rights violations, and wrote about those issues the official press would not touch with a ten foot pole. In short, we did independent reporting.

2 – What were the publications?

We put packets of information on the Internet, particularly on Nueva Press Cubana and Radio Marti and other media, especially on-line. We had no particular purpose nor exclusivity in the news we issued: the information was open to all the media who wanted to use it.

3 – It seems essential to know the details of your arrest. When was it, what time, what happened? Were there irregularities?

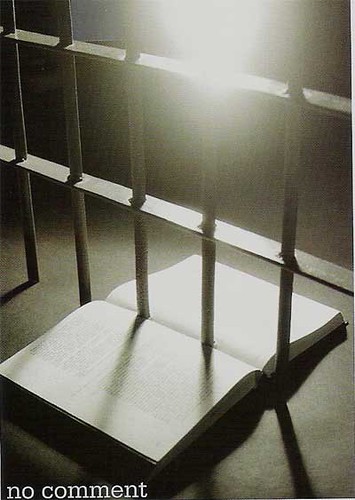

I was kidnapped and help hostage by Castro’s Political Police on March 18, 2003. Days earlier I had half-locked myself in the house to read some books that had arrived (banned by the dictatorship, of course, and classified as “enemy propaganda”). They were the memoirs of Huber Matos, When the Night Comes; Narcotrafficking: Revolutionary Task, by Norberto Fuentes, and at the moment I was kidnapped I was reading, The Secret Wars of Fidel Castro, by Juan Francisco Benemeli. I had only read 80 or 90 pages when I was taken. That day my wife went to Havana to spend a few days with her son. About a quarter to four in the afternoon I was going downstairs — I live on the third floor — to go to the supermarket when an invasion of thirteen or fourteen agents from the Political Police were coming up. They intercepted me on the stairs, I didn’t make it to the second floor. I was told I could not go anywhere, I was under arrest, and they searched the house.

One officer had a video camera and another a still camera and they were taking photos the whole time.

The search began after four, because they put on this act of looking for two witnesses. Something that struck me was that none of my neighbors wanted to participate and they were slow to get started. Finally they found two people and when one of them showed his ID card to assent to the act, I could see that his address was in Havana, he wasn’t even from here in Ciego de Avila; the other one was from SEPSA — Specialized Service for the Protection of Society Anonymous — that is from an agency of the Ministry of the Interior that watches over the hard-currency stores and those things. He, of course, could not refuse and he did live in my building but on the other staircase.

I was very worried. They told me I was arrested and my wife had gone to the capital. I was alone in the apartment with my two dogs (two dachshunds) and I was worried about leaving them alone. I had to get someone to take care of them.

A little past five someone knocked on the door and when I opened it it was my wife. She explained that they came to look for her at the bus station and told her that her house was being searched.

Everything ended around eleven at night because they found my archive. Not that it was hidden, it was just in a room that I used as an office that didn’t have any light because the bulb was out. They found two or three bags filled with writings, denunciations, and the one in charge of the search said, “If we had to read them one by one we would be here until tomorrow, we will count them all.” There were about nine documents.

At that time they took me to the cells at State Security.

4 – Before concluding on the search. Was the order signed by the relevant institutions? Did they meet the legal requirements for it to be valid?

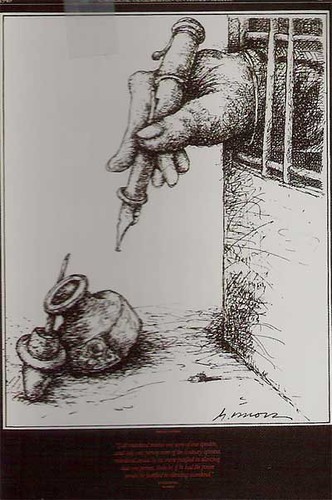

They never showed me the search warrant. I asked, “Do you have a search warrant, an arrest warrant?” They said, “We have a search warrant,” and went into the house. They showed me neither the search warrant nor the arrest warrant.

There was a State Security official who supposedly made a record and wrote down what the others found. They found no bombs, nor revolvers, nor pistols, nor grenades, nothing. They found a typewriter, a video camera, pencils, pens, office supplies for carrying out independent journalism. In addition to books, magazines, literature, poetry. Nothing more. They presented this at my trial to say that I was a mercenary.

5 – Your family, how did they take the collapse of their lives?

Imagine it, my wife left for Havana and was intercepted: Your husband is arrested, they are searching your house. For many years I had been involved in pro-Human Rights activities and the independent journalism. Somehow I was used to it, I had already been in prison in ’95 and ’96. It wasn’t the first search nor the first arrest.

She knew there was a sword of Damocles hanging over my head, possible imprisonment, but it always comes as a surprise. We did not know that they had started a crackdown that would last four days. For example, that same day, the 18th, Pablo came to the house in the middle of the search. A State Security agent told him, “Pablo Pacheco, get out of here, Argüelles is under arrest.”

The following day, in the afternoon, I was in the cells, and I heard someone calling and calling me. It was Pablito, they had just arrested him and brought him to the cells. He knew, because he had talked to Raul Rivero, that the arrests were nationwide.

6 – Under what specific charges were you convicted and what was the procedure of the court? What evidence did they exhibit at the trial? Did your lawyer defend you?

When they were still in my house, I asked the captain, “Why are you arresting me?” And he told me, “For violation of Law 88.” The trial was on Friday, April 4, at the Court of Ciego de Avila Province. It lasted from nine in the morning until four in the afternoon. There was a large police deployment, the car in which I was brought there was guarded by police patrols. They closed the streets around the court. An official from the prosecutor’s office asked us days earlier for a list of relatives who would attend the trial and if they weren’t relatives they could not attend.

When we arrived the room was full of people from the Communist Party, from the Army (FAR), the Interior Ministry (MININT), labor groups … their people, pro-Castro. From my family only my wife and my sister attended, and from Pablo’s, his wife, his son, and I can’t remember if one brother came.

I did not have a lawyer and they assigned me one from the office. A girl who had just graduated, I was her first case. We only saw each other once before the trial, for half an hour, in the same room where State Security had interrogated me. Ultimately she, who was my defender, defended nothing because she couldn’t.

Pablito did appoint a lawyer. It was very amusing to me because when she referred to us she would say, “the counterrevolutionaries,” and I was thinking, “if this is our lawyer calling us counterrevolutionaries…” A curious detail: the same lawyer Pablo hired, a few years later she won the visa lottery and went with her husband to the United Stated. But my attorney played a much better role and never called me a counterrevolutionary. When I went to testify the president of the court torpedoed me, she wouldn’t let me say a single word and my lawyer even protested. During the lunch break she told me, “I’m going to keep on protesting. I’m going to complain because you have not been allowed to speak in your defense.”

The trial was completely rigged, they knew what was going to happen. There were no witnesses on our behalf. The prosecutor brought people from Pablo’s CDR because in my block there weren’t any. At the request of my prosecutor — that is, in the provisional findings of the prosecutor — two prisoners from the Canaleta Provincial Prison here were supposed to testify at the trial, as a complaint, that I had talked to Radio Marti about their medical care. They weren’t there and then they presented a doctor from the Medical Services of the Ministry of the Interior, a dermatologist. She said that the consultation was Thursday or Friday at the prison and the medical care was very good.

The prosecutor asked for 26 years and they sentenced me to twenty years. The provincial court clerk gave me the sentence the morning after the trial.

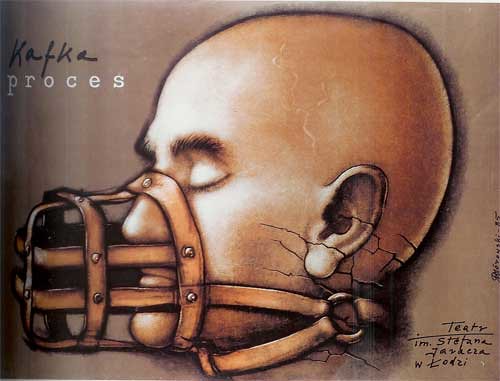

7 – The Cuban jails are unpresentable. The rapporteur for torture and ill-treatment was unable to visit Cuba last year because the Cuban government would not allow it. Tell me about your life in prison, the journalist behind bars, how you managed to hold onto your morals and principles in such terrible conditions.

I always speak for myself and also my brothers, but in this case for myself: I am very convinced of what I’m doing and since I began this fight in 1992 I knew everything that I was exposing myself to. I knew the risks I would run and the sacrifices that I would have to make. They could expel me from my workplace. They would monitor me and I would be declared an official non-person for denouncing human rights violations. Because Cuba is a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

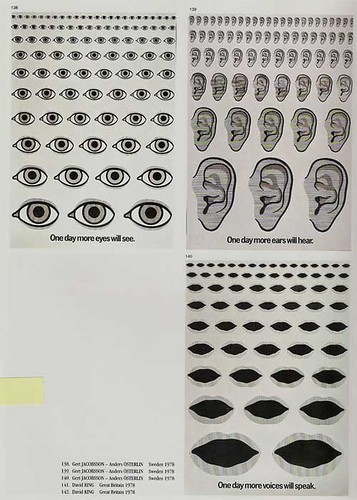

In here we live in appalling conditions, incredible overcrowding, poor nutrition and medical care. The snitching — speaking in popular terms — is enormous, the police informers are in the thousands. I am constantly observed, there are many eyes on me because every time there is a violation of human rights I investigate and denounce it, at the risk of what might happen.

To work and write in prison is not easy. Life here is hard: this is not a day care center or a school in the countryside, nor an urban school. It’s a prison with a series of psychedelic elements, psychiatric cases, mentally retarded, dangerous people who have murdered, raped, who have committed all sorts of crimes. People who will never leave prison. It’s a social dump and you’re forced to live with it. There are, of course, normal people, good people who never should have come to prison or who were punished excessively for some nonsense.

All the time the police tell you what to do, who you can talk to, who you can meet. But we have to carry on even though the environment is hostile.

The sanitary conditions are appalling. I am in a cubicle with room for two people and there are six people here, there are two triple bunks. The bathrooms are holes in the ground and we get water twice a day. The water isn’t drinkable and it’s for everything: drinking, bathing, cleaning.

Health care is terrible. For example, there is a boy here who from the tenth day had X-rays ordered and he still hasn’t had them: either there’s no guard to take him or there is a guard but the technician didn’t come. There are cases where the doctor will come and prescribe a medicine and then you’ll wait eight or ten days and the medicine doesn’t come. There’s nothing. Sometimes you make it to the infirmary and there’s not even any pain medication.

Generally, if you go to the infirmary it’s for your amusement — they themselves say that — because you see the doctor and he ignores you. There have been many deaths here in the prison for lack of medical attention. I’ve reported a few.

The prison staff always justifies the deaths in some way. In short, the system is one thing: everything belongs to the State and responds to the government. The doctors are young people who have just graduated and this is their first work experience as part of their social service obligation. Before they start work they meet with the director of the prison and he tells them the prisoners pretend to feel ill so they can go to the infirmary to traffic in drugs or to look at the nurses. Then the doctor sees you as a faker and treats you like one. On the other hand the doctors, the women, start to have sex with the prison director and then they feel protected no matter how bad their professional work is.

8 – Do you think you will finally be released? What is the first thing you will do when you are a free man again?

I would speak of my release, though I feel free even though I’m a prisoner. I think that yes, some time, some day of some month of some year, I will be released. The first thing would be to call my brother Guillermo El Coco Fariñas and tell him I’m at home with my wife. And my first outing would be to go to Santa Clara and give him a hug.

Then I will continue my struggle peacefully, civilly, for the respect for rights, freedom, and the dignity of the human person.

But even if I am not released, from here in the Canaleta prison, or from any other prison where they confine me, I will continue defending the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

November 23, 2010