The Government has just published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba, the legislation that authorizes the purchase and sale of private property.

Translated by Regina Anavy

November 3 2011

English Translations of Cubans Writing From the Island

The Government has just published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba, the legislation that authorizes the purchase and sale of private property.

Translated by Regina Anavy

November 3 2011

It’s almost a siege. Never before, since Cali 1971, when Cuba took second place by assault in the continent’s multi-sport games, moving Canada to third place, did the green caimán feel the breath of its opponents so close.

Then in Rio 2007, Brazil sent Cuba into water up to its neck. With a final push of athletics and combat sports, they made a killing in the shooting event in the land of samba and soccer. In a duel of power to power, Cuba won 59 gold medals to Brazil’s 54.

Now joining the effort are Canada and Mexico, the home of the Sixteenth Pan American Games, from October 14-30, in Guadalajara, with the participation of 5,996 athletes from 42 countries, including 442 Cubans. But Brazil feels it’s now time to take out the U.S., always the champion.

Brazil is very serious about sports. Today, Cuba excels in all team sports, except baseball. Even in combat events and athletics, which Cuba often sweeps, Brazil now is a rival to watch out for.

In the last world-wide judo contest, Brazil won more medals than Cuba. If their best male and female athletes go to Guadalajara, Cuba will have a hard time dominating the martial art.

Now boxing is not the flagship of yesteryear. Forget about winning nine or ten gold medals in the engagements of America. After a legion of fighters switched sides, they decided to sign as professionals, and the Cuban boxers have ceded territory.

It’s true that in the last World Cup held in Bakú, Cuba ranked second, with two gold medals and one silver. But Brazil made history with the gold obtained by the light welterweight Everton dos Santos, and the bronze of Esquiva Falcâo in the division of at least 75 kilos.

And it’s likely that Everton and Dodge will compete in Guadalajara. Moreover, Mexico, Venezuela, Canada, Dominica and the United States have some individuals who might take away the gold medals from Cuban boxing.

To secure second place in these Pan American Games, Cuba is confident that the wrestlers will sweep in freestyle and Greco-Roman. And take between nine and eleven titles in athletics. The United States will get third and fourth, giving options to the island’s athletes.

Jamaica, a potential number one in sprinting, will compete with runners of low rank. But we know that number ten of the Jamaican team wins at short-distance runs.

If the United States doesn’t keep a commitment to swimming and uses kids who aren’t very fast, then there will be a golden opportunity for Brazil to take some medals out of the pool.

Mexico can also outstep Cuba in different disciplines. Like Venezuela, Argentina or Canada, who are not made of stone. Brazil ought to impose itself in several group sports.

In volleyball, either beach or court, and between women and men, the yellow-greens should sweep up. If Cuba can achieve a good result in cycling and boating, it will have more options to stay in second place. Anyway, with countries winning even second place, the number of gold medals for Cuba should not exceed 50.

Look, among the 361 sports events that award medals, Cuba withdrew from participating in 111. Among others, Cuba will not compete in wrestling, football and women’s weightlifting.

In swimming, the Creole presence will be symbolic. The task of the Indian will have to do with combat sports and athletics, with its best exponents participating, say Olympic champions Dayron Robles or Yargelis Savigne, valued in the triple jump, Yarelis Barrios in discus, Yipsi Moreno in hammer-throwing, the decathlete Leonel Suárez and the phenomenon of the pole-vault, Lázaro Borges.

Taking account, it’s likely that Cuba can beat Brazil by taking two or three medals. But surely the Brazilians will be close behind. Suffice it to say that after four years, the colossus of the South must displace the Greater Antilles in the continental games.

Meanwhile, the United States continues to sleep soundly. It is the most powerful nation in the sport of the Americas. Although it has had its scares: in 1951 Argentina ranked first in the Pan American Games held in Havana in 1991, Cuba relegated them to second place.

But it has rained enough. And Cuba has lost many points in athletics. For various reasons, from the systemic economic crisis that has ravaged the island for 21 years to the incessant defections of athletes.

Mexico will be a red dot on the lens of Cuban athletes. The United States is on the other side of the gate. And that will always be a temptation for those athletes who dream of competing as professionals and earning high salaries.

Of course, Mexico is burning. There have been 44,000 deaths in the last five years. A wave of violence that changes these Pan American Games into a high-risk event.

To neutralize any threat, Felipe Calderón placed 11,000 specialized policemen, manned airplanes and Blackhawk helicopters to clear the zone of the feared gunmen of the Sinaloa cartel and the paramilitary bands in the style of the Zetas.

The Mexican authorities have declared they have not detected any suspicious activity and security is guaranteed 100 percent in Guadalajara 2011. But in sports, the threat to Cuba is called Brazil.

Translated by Regina Anavy

25 October 2011

Outside Cuba there are revolutionary intellectuals who chose to emigrate when it was impossible to make their thinking public. Subtly, the access to publishers and university classrooms was blocked.

There is also a generation of young professionals who are now between 30 to 40, who are educated in revolutionary principles. They left for economic reasons but also because of disappointment and feeling tired of being forced into subservience. I know a lot, because it’s my children’s generation. They are thoughtful and cultured people. But we are scattered around the world. If we were called, if someone calls us to return to Cuba, many would return to claim the right of every Cuban revolutionary, now, to think about the country’s future. It’s time to call on those who are outside to return to the country that we love and to say it, because it’s clear that Fidel’s convalescence is opening undesirable doors.

These doors usually are opened toward internal repression of thought and external acceptance of pseudo-socialist models: capitalism with a repressive state.

Translated by Regina Anavy

January 2007

After so many years of being gagged, we couldn’t hope for anything other than this discordant chorus in which voices climb, one above the other – you have to answer the opinion issued yesterday, also be quiet, stop just long enough to be read and overlap with others that are already collected on our computers or under the covers of some ordinary-looking file. All there: some reasonable; others, excessive. An indispensable whole, to understand the hurt and pain that we Cubans carry on our conscience.

Just like Galileo Galilei they showed us the instruments of torture, this time on television. The functionaries of culture and/or the Party must have been amazed that the same silence as always didn’t happen. You’d have to be very naive – I know it’s a very polite adjective – first, to swallow the story that it’s a perverse sequence of blunders, and, secondly, to believe for a second that Cuban television is the place where “belligerent ignorance” is located. Alfredo Guevara should know this full well, because since 1960 he has called on Cuban intellectuals to please have the clarity to follow the objectives and the inspiring example of the Revolution: “The only limit to freedom is freedom,” a witty phrase in which it’s unclear what freedom is, but clear what its limits are. With the passage of time and the vicissitudes of practice, this call was made less obsequious.

Can anyone defend the idea that the Round Table is a TV show? Is it an initiative of the “ignorant” who, according to Guevara, conspire against the revolution?

There is no doubt that the government of Cuba has known very well how to keep people at bay for 48 years. One of the reasons many compatriots left was to be able to express an opinion, something they couldn’t do here without regretting the consequences. It’s been some time since the regime showed how it can reduce a man’s book of poems to a pulp, along with his spirit. Now we have the poet Delfín Prats to prove it. The regime turned the others into a show.

Literally.

We who live here shouldn’t forget that wherever we are, we’re Cubans, and the homeland is ours not just by happening to live in it. On matters of Cuba, any Cuban has the right to give an opinion. José María Heredia does it every day in his clear verses:

“Don’t forget our past. We need it desperately to be able to decipher our present and to confront our future.”

In the mediation during Fidel Castro’s meeting with the intellectuals, at the José Martí National Library which discussed the theme of artistic creation, after the prohibition of the documentary film P.M., in June 1961, Alfredo Guevara said: “I want to clarify, of course, I am not one of those who’s afraid. I don’t expect more of the Revolution than positive things in all areas, including the field of art, including the field of creation, and I believe that with the Revolution we have found all we need to express ourselves, all who have something to say, all who want to say something. We have found the opportunity to say it with absolute freedom, and to say “no” not just in a small group of bourgeois or fans, but to say it before all our people, to the broader public, the public that connects the entire nation. Because the Revolutionary triumph is the story of the entire nation with its own purposes, or at least that is how I understand it, specifically for artists.” (Revolution is Lucid, Ediciones ICAIC, 1998, p. 181)

This seems to be the answer to a very brave opinion issued in one of these meetings. A man said, aloud, that he felt fear. His name was Virgilio Piñera.

We would diminish the scope of Virgilio’s declaration if we don’t hold onto a startling date. In 1952 he published a strange novel, La carne de René (Rene’s Meat), a tale of the terrors that surround meat. René, the protagonist, has received an inheritance from his father and grandfather in the cause of meat. So his life has been a series of escapes and imperious resistance to his calling. With his refusal to accept the cause, René shakes the precepts of an established world. In turn, that order will use all its weapons to persuade him. This is a sinister game in which each man has been a victim, but also a victimizer. It’s worth mentioning this date as the beginning.

You know the rest of the story. Virgilio died in 1979. They say that his funeral was attended by very few people. In 1968 he had written Dos viejos pánicos (Two Panicked Old Men). He had had the bad taste to insist on fear as a subject at a time when displaying macho swagger was demanded.

Now in a statement by the UNEAC Secretariat, in a predictable text written in an irritating language, we are called on to not abandon the flock, to remain as silent as lambs of the purist stock, now, when we are threatened that speaking out means we are in favor of annexation. I can’t forget the emaciated figure of Virgilio, walking to a microphone to confess his fear.

Leticia Córdoba

Havana, February 16, 2007

Translated by Regina Anavy

On September 28, 1960, while homemade bombs and firecrackers were being detonated by his political opponents, an angry Fidel Castro created the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR). From the balcony of the north wing of the Presidential Palace, the guerrilla commander, recently returned from a tour of New York, argued the need to monitor all the blocks in the country for the “worms and disaffected,” to protect the revolutionary process.

It was one more step in the autocratic direction in which he was now navigating the nascent revolution. Another deep stab towards the creation of a totalitarian state.

From 1959, Castro had struck a mortal blow to press freedom when, methodically, between promises and threats, the main newspapers of Cuba were shut down. He eliminated the rights of workers to strike and habeas corpus. The legal safeguards for those who opposed his regime were almost nil. He concentrated power. And he made political, economic and social policies by himself, without previously consulting ministers.

The process of establishing himself as the top pontiff in olive green culminated in 1961, with the radicalization of the revolution and the strangulation of the pockets of citizens who dissented against his government.

The CDRs are and have been one of the most effective weapons to collectivize society and get unconditional support for Castro’s strange theories. And one way to manage the nation. They were also the standard bearers at the time, shouting insults, throwing stones and punching the Cubans who thought differently or decided to leave their homeland.

The CDRs are a version of Mussolini’s brownshirts. Or one of those collective monstrosities created by Adolf Hitler. More or less. Over 5 million people are integrated into the ranks of the CDRs on the island.

Membership is not mandatory. But it forms part of the conditioned reflexes established in a society designed to genuflect, applaud and praise the “leaders”.

Although many people have no desire to take part in revolutionary events and marches, or to attend the acts of repudiation against the Ladies in White and the dissident protestors, as if they were on a safari, in a mechanical way at the age of 14, most Cuban children join the CDR.

It forms part of the greased and functional machine of the Creole mandarins. A collective society, where the good and bad must be doled out by the regime.

Two decades ago, with a state salary you could buy a Russian car, a refrigerator, a black and white TV and even an alarm clock. If you surpassed your quota in cane cutting, you were demonstrating loyalty to the fidelista cause or you were a cadre of the party or the Communist Youth.

The others, those who rebuked Fidel Castro’s caudillismo, in addition to being besieged and threatened by his special services, did not even have the right to work.

The CDRs played a sad role in the hard years of the ’80s. They were protagonists in the shameful verbal and physical lynchings against those who decided to leave Cuba.

It can’t be forgotten. The crowd inflamed by the regime’s propaganda, primary and secondary students, employees and CDR members, throwing eggs and tomatoes at the houses of the “scum”, to the beat of chanted slogans like “down with the worms” or “Yankee, you’re selling yourself for a pair of jeans”.

Among the dark deeds of Fidel Castro’s personal revolution, the acts of repudiation occupy first place. In addition to monitoring and verbally assaulting opponents, the CDRs perform social tasks.

They collect and distribute raw material. They help deliver polio vaccines. And, from time to time, less and less, they organize study circles where they analyze and vote to approve a political text or some operation of the Castro brothers.

That bunch of acronyms generated by the sui generis Cuban socialist system, CTC, FMC, MTT, UJC and FEU, among others, are “venerated NGOs”. According to the official discourse, those who by sword and shield support the regime.

In this 21st century, the CDRs, like the revolution itself, have lost steam. And their anniversaries and holidays are scarce. The night guards are rare birds. But the CDR members still keep their nails sharp.

They are the eyes and ears of the intelligence services. Snitches pure and simple. In one CDR a stone’s throw from Red Square in Vibora (which is not a square nor is it painted red), some of the species remain.

Now one has died. A lonely old man and childless, a factory worker, who was noted for his daily reports about “counter-revolutionary activities on the block”.

Two remain active. They have antagonized the neighborhood by their intransigence. All who dissent publicly in Cuba know that there is always a pair of eyes that watch your steps and then report by telephone to State Security.

Over time, you get used to their clumsy maneuvers of checking up on you and interfering with your private life. They inspect your garbage, to see what you eat or if you bathe with soap you bought in the “shopping”. Sometimes they make you laugh. Almost always they make you pity them.

Translated by Regina Anavy

September 27 2011

There are dates that leave their mark forever. The attack on the Twin Towers of New York is one of them. We probably all remember what we were doing at the time. How did we learn about it? What did we experieince?

September 11, 2001 appeared to be a Tuesday like any other in Havana. Dawn had come without clouds and with a full sun. At 8:45 a.m., when the first aircraft crashed into the Word Trade Center, I was still sleeping.

Around 9:20 a.m., I began my routine. Reviewing some notes to send to Encuentro en la Red (Encounter on the Web). Combing through the news on Cuban radio. In the afternoon, listening to the news from the BBC, Radio Exterior of Spain, Radio France International or Voice of America. Then going out and talking with people on the street.

I remember that Radio Reloj was going on and on about the state of the economy on the island. About 10:00 I received the newspapers, Granma and Juventud Rebelde. With more of the same. Briefly it was recalled that September 11 was the 28-year anniversary of the Pinochet coup in Chile.

I was alone in the house. My sister Tamila was working. My niece Yania was in school. My mother Tania Quintero, a freelance journalist, had gone early to “forage” for food in several agromercados.

Around 11:00 a.m., a neighbor in the hallway of my building shouted: “It looks like there was a huge accident in the United States; they’re showing it on Channel 6”. I connected the TV. National television, something unheard of, had linked to CNN, and in the background, two reporters commented on the news.

The images were horrifying. Again and again they showed the airplane hitting the structure of concrete, steel and glass, like a knife going into a stick of butter.

The telephone began to ring insistently. Friends and relatives were stunned. We could not believe what we were seeing. Those with relatives in Miami were trying desperately to call them for more information. The phone lines with Florida were jammed.

I still have on my retina the powerful images of desperate people who threw themselves to death from the top of the towers. When the buildings collapsed, leaving a huge cloud of dust and soot, and a chilling roar that the people of New York would never forget, we who followed the news knew that the world had changed.

In the space of the afternoon we knew that a plane had hit the Pentagon. A fourth plane crashed in a Pennsylvania forest, thanks to the courage of the passengers, who by a phone call knew what had happened in the Big Apple.

That night, Fidel Castro spoke in the Sports Coliseum to numerous medical students. The Cuban government authorized American planes to fly over Cuba and use the island’s airports and air corridors. The sole comandante offered medical aid.

The United States was under a terrorist attack. We all knew intuitively what would come next. War. In those days, a large part of world was in solidarity with the northern nation. It did not know how to capitalize on that support.

Perhaps the best option was not planes and smart bombs buried in rubble, caves and hideouts of the Taliban in Afghanistan. I am one of those who think that an operation of special services, operating with close international cooperation, would have had better results.

But the Untied States wanted revenge. Some 6,000 people were injured and about 3,000 people lost their lives. Many families couldn’t recover their remains.

War will never be a good option. Ten years after the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers, the victims total more than one million dead and wounded. The world has not been made more secure. There are fewer dictators and rogue leaders, but democracy at gunpoint has not brought order in Afghanistan or Iraq. Quite the contrary.

Thousands of U.S. troops are bogged down in those nations. Almost a decade after the attack on New York, it took a special forces operation to hunt down and kill Osama Bin Laden.

Al Qaeda is still alive. The autocrats and tyrants continue trampling on the basic freedoms of their peoples. It’s good that the United States and other nations demand democracy and respect for human rights in countries where they are violated.

But not from the cockpit of an F-16. Undoubtedly, blood, devastation and fire are rather strange ways to learn lessons on democracy.

Translated by Regina Anavy

September 9 2011

The political and fiscal plot against corruption has obvious political overtones. Many are asking if Raul Castro is playing hard ball or leaving the road to his political and economic adversaries.

Let’s wait and see. Meanwhile, the mystery continues on the island. Detentions after detentions. Surprise audits of Gladys Bejerano’s accounts. And the Chinese padlocks on the prison cells open to welcome new groups of guests.

In their crusade against corruption and crime, for the last year almost a hundred officers of all ranks have been sleeping in triple bunk beds. From those who are on the top of the pyramid, like Alejandro Roca, to the nurses and doctors who emulated the Nazis in the way they mistreated and killed patients in a psychiatric hospital.

Now, on the threshold of autumn, Havana is not setting off firecrackers. The opposition becomes increasingly bold every day and loses its fear of blows and insults.

The police know that any street protest, even a small one, can cause a spark. And they suffocate it with violence. Alarms go off everywhere. Palma Soriano, Guantánamo, or a plaza in Havana where a group of women shout for freedom and political change.

The fear of any event outside the official program is palpable. Go down Infanta Street, at the corner of Santa Marta, Centro Habana, where you find the Assemblies of God Pentecostal church. A month ago, 61 parishioners decided to lock themselves in for a spiritual retreat.

And faced with doubt and the novelty of the event, just in case, the police blocked the streets around the temple. When they saw that the “enlightened” pastor Braulio Herrera and his followers were not newly-minted dissenters, they yielded.

You can now pass through the neighboring streets. But a large number of civilian police and special services prowl the area. In addition to certain social tensions, there is the widespread discontent of the people, tired of the old government and its economic inefficiency.

Cuba is now a tinderbox. The slightest touch of a match could ignite it. If there haven’t been street explosions of any magnitude it’s because the political map of the island is so strange.

You could say that 15% of the public supports the Castro brothers. Another 15% is affiliated with the opposition. While the rest, 70%, is fearful and indifferent. They are simply spectators.

To add insult to injury we have the pitched battle, without much informative fanfare, unleashed by General Raúl Castro against corruption. The main enemy of the revolution, he said. It’s a war of survival. And the clans. The winner will have free rein to design the political road map for Cuba in the coming years.

If you analyze the chess moves of that eternal conspirator named Raúl Castro, you can deduce that, despite denying the supposed differences of opinion with his brother Fidel, in practice he has been dismantling, patiently, all the framework erected by the historic leader of the Revolution over five decades.

From grandiose mandates like the “Battle of Ideas,” schools in the countryside, the excessive use of television as a teaching method in primary and secondary schools. And, of course, he has removed almost all the men loyal to Fidel.

He has made a vast change in the furniture. From the fidelistas, there are only three important figures left: Ramiro Valdés Menéndez, 79 years old, José Ramón Machado Ventura, 80, and Esteban Lazo Hernández, 67.

Lazo is the classic loyalist. If he accepts the new direction, he will continue as vice president of the Council of State. It’s true that he won’t liven things up, but he will be guaranteed his foreign trips and the amenities that belonging to the Politburo confers. For now he’s not a threat to Raul Castro’s crusade.

With Machado something else is happening. The General wants to keep him close. Ramiro is the dangerous type. Because of his history and the influences created in his years as the Minister of the Interior and the head of special services.

The blows against the Canadian businessmen of Armenian origin, Sarkis Yacubian and Cy Tokmakjian, could be interpreted as a warning message to Ramiro.

It’s a match between two big-headed men. In my opinion, Raúl Castro and Ramiro Valdés are the most important and the most powerful men in Cuba of the 21st century. Some believe that the crusade against corruption is one of Raúl’s strategies to dethrone Valdés.

It seems to me that the upcoming party conference in January 2012 will be a reckoning. Only one of the two will remain.

Translated by Regina Anavy

September 18 2011

In order to make a modest contribution to what appears to be a great confusion when translating, I gave myself the task of searching in dictionaries, to clarify for that great actor who often visits us, Danny Glover, and who is said to be such a friend of Cuba (meaning the government), the true meaning of the word “spy,” which he so often confuses with “hero.”

According to the Larousse dictionary, illustrated manual (1969, pages 365 and 474):

Spy: a person charged with gathering secret information on a foreign power.

A person who on the sly observes the actions of another or tries to know his secrets (this last meaning suits the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution).

Hero: Someone who performs a heroic deed.

Main character of a literary work, adventure story, film.

Person who performs an action that requires courage.

I hope this helps clarify any confusion about the use of these two nouns, which are so often misused in our media.

Translated by Regina Anavy

September 20 2011

It’s a war of power against power. On one side, General Raúl Castro manages military counter-intelligence, pulls the strings in the major economic sectors of the nation and has consolidated his cabinet with loyalists as bullet proof as atomic bombs.

It’s a war of power against power. On one side, General Raúl Castro manages military counter-intelligence, pulls the strings in the major economic sectors of the nation and has consolidated his cabinet with loyalists as bullet proof as atomic bombs.

But behind the scenes, his adversaries look at him sideways. They are high-flying bureaucrats, local business managers, heads of large wholesale storehouses for food, textile and electronics waste, construction materials, and managers of tourist facilities.

This fat layer of bureaucrats has dedicated itself to creating a dense network of diversion and theft at the expense of state resources. They have created a parallel economy.

For many years, the envelopes with thick wads of cash and all types of gifts have landed happily in the pockets of certain senior party officials and dishonest government employees. The local bureaucracy has taken root in the bone marrow at almost all levels of society.

Like the marabú weed, it will be difficult for Raúl Castro to cut them off at the root. They are enemy number one. Forget about internal dissent; for the moment, it doesn’t count. It’s a fight against the demons that provoke these systems of command and control and the military economy.

There are tangible indications that at the first sign of change, the true opponents of Castro II will go on strike to pull the floor out from under him in order to slow the economic reforms.

See for yourself. According to the official press, in August the production of beans tripled over the past six months: 90,000 tons. This is no small thing. That figure is the amount of grain that is consumed annually on the island.

However, despite the high cost of black and red beans, which are sold in private markets at 12 and 15 pesos a pound (half-kilo), only 9% were for sale. The rest was bogged down in the warehouses.

Or they were distributed by the usual clandestine channels that permeate life in Cuba. And that work like a Swiss watch. It happens that beans are sold in the state market at 8 pesos.

The corrupt bureaucrats who control the supply chain prefer to hold onto them and sell them out the back door, to supply the black market or the private agro-markets. So they always have beans.

The marketing network is an unresovled matter for the Ministry of Agriculture. Tons of bananas, fruit or tomatoes rot after harvest, for lack of packaging or means of transport.

This leaves the door open to the czars and clans who control the food supply. Who for years have made money thanks to the inefficiency of the Ministry of Agriculture. To this add the absurd policies of the government, which stipulates that 80% of the agricultural production of private farmers must be sold to the state.

At laughable prices. So private farmers must cheat to keep more of their crop. Or they let their cattle and oxen graze on railroad tracks or the highway, to be killed by “accident.”

Cuban farmers own the livestock, but they cannot market or sell the meat. Only the state is allowed to do that.

The pricing policy is irritating. A kilo of onions costs one peso and 30 cents in the store. With one peso in Cuba you can only buy a newspaper, take a city bus, or get a cup of coffee.

Now many farmers steal from their own production. To sell in markets governed by supply and demand. There a pound of onions sells for 10 pesos.

It’s precisely in the collection centers, refrigerated storage and warehouses where the cartels and mafias operate at full throttle, enriching themselves and profiting from the food supply.

Right now Raúl Castro is someone they can’t stand, someone who is going to fuck up their business dealings. The only thing left is to fight him.

They use devious strategies. They don’t show their true feelings. Nor do they publicly complain about the government and its policies. They are kings of pretense. They know how to pull the strings.

To create obstacles they have a panoply of excuses. From lack of oil, transport, spare parts or a shortage of workers. They know how the system works better than anyone; they have lived off it for years.

The same thing is happening with construction materials. According to the official media, industry warehouses are over-stocked with cement, slabs, floor tiles and toilets.

However, despite being sold without subsidies in the municipal markets, people who try to repair or build a house always get “No” for an answer when they ask for certain materials.

Only low-quality materials are for sale. Or something else that is so expensive that many prefer to buy it on the black market or with hard currency, for a better rate. Remember that 60% of homes in Cuba are technically in fair or poor condition.

Therefore, construction materials are in demand and urgently needed to prevent roof collapses. General Raúl Castro wants the street stalls and agricultural markets to be saturated with products. So families can have a glass of milk.

And for the disappearance of so many absurd regulations for traveling or buying a car or a house. But his wishes and reforms go cautiously forward at a turtle’s pace.

As an adversary, he has a monolithic wall of corrupt people and bureaucrats who have joined ranks. There are two options: Either he will demolish them, or they will demolish him.

Translated by Regina Anavy

September 15 2011

So Orlando Zapata gave himself up with the only weapon he had. Guillermo Fariñas then went to the edge of the abyss, from where it is assumed there is no return, but his spiritual energy carried him and brought him back; besides, the fight is not over, that was only one chapter. Both Zapata and Farina are examples to follow.

Cuban bloggers have endured intimidation, arrests and kicks. And yet it seems little to us if we compare it to the infinite pleasure of communicating, delivering opinions for those who prefer silence out of the fear of retaliation.

The agents of the political police understood that they’re clumsy. Although they continue to engage in physical aggression, now they walk a fine line. They have set in motion the machinery of their means of communication and counterintelligence. Yoani Sánchez was the first, then the blogger Diana Virgen García.

Just around the celebrations of July 26, 2009, the most important holiday of the regime, I was arrested. My ex-wife, after four years of separation and having a relationship with a senior police officer named Pablo, the superior of the Sector Chiefs of the municipality of Plaza, went to the police station at Zapata and C, and accused me of rape. Luckily, at that time I was far from the place that she chose for the false accusation. I was with friends who served as witnesses in the presence of my current partner.

The officer who notified me about the case told me that my ex suffered from a mental disorder, and it was possible she would have to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. He said that after making the complaint, he explained to her that she would have to take it to Legal Medicine to corroborate that she really had been raped: it was the only way to present such an atrocity before a trial. She refused. Then she showed a medical document where she was diagnosed with an injury to her ear, and a picture of some marks behind it, such as scratches. The officer let her know that in order for the document to be found valid, she had to return to the doctor with a policeman he would assign to her. She also refused to consult the doctor. Regarding the photo, the officer insisted it would be valid only if it had been taken by police specialists, but as there were no visible marks, it didn’t make sense that experts would appear.

Then my ex rescinded the above allegations and said that she was accusing me of stealing some family jewels. The officer began to ask her for a description, to later corroborate it with her family and friends, so they could guarantee that the jewels were really hers, and to compare them with some photo where she was wearing them. She again refused.

She then asked, as if playing a children’s game, that they take another statement, about my stealing money in several currencies, CUCs, dollars and euros, whose total sum barely surpassed $100.

The officer who assisted me could demonstrate to her, with several witnesses, where I was at the time declared by my ex, while she couldn’t present any witnesses or evidence that would incriminate me.

The officer said I could go without imposing any injunction on me. A month later, I passed about sixty meters from my ex. The next day she tried to accuse me of harassment, but they did not accept the complaint

Fifteen days later, at the place where my ex lived, at dawn, there was a short-circuit in some wires near a bush of dry leaves, and a fire broke out. The firemen took more than an hour to arrive. The neighbors had warned them about the power failure and that an accident could happen. My ex was not at home, but the next day, when she appeared, it was at the police station, and she accused me of attempted murder.

However, several caretakers for neighborhood businesses at the residence saw no one near the place; in fact, it’s nearly three meters high and there are two locked gates that the firefighters had to break down.

Twenty-four hours later I was summoned by the police, and witnesses showed where I was at the time of the fire. And they agreed to let me leave. Then, a senior official insisted that I would have to post a bond of 1,500 pesos. Obviously, it was not by chance that days before I had received an invitation to the Festival of the Word in Puerto Rico, signed by the writer Mayra Santos-Febres. With the imposition of the bond my leaving the country was prevented, along with the possibility of being able to communicate with the international media.

Days later they changed the police officer on my case. The new one was announced as Captain Amauri, and in a short time, he was apprised of all the imaginary complaints for which the prosecutor requested more than fifty years in prison.

There was an alleged witness. I don’t know if it was a matter of one complaint in particular or all of them, but the fact is that the day they began the cross-examination, he shouted that they couldn’t force him to testify against me, that he did not know me.

On leaving the police station, the alleged witness presented himself at my house and before my neighbors explained what actually happened. He videotaped the confession.

Then, last July 25, I was summoned to the station because the alleged witness, the only one they could manipulate, had made a complaint against me of threats: “coercion” to not testify against me. They held me for 18 hours without food or water. Only when Castro’s speech for the celebration of the assault on the Moncada barracks was finished did they release me, without the alleged victim having appeared.

I came home and copied 100 CD’s of the confession of the “witness” and delivered it to the police and to whatever media of disclosure exists in this country, although they don’t function. And like the gesture that quiets the orchestra, there was silence.

Today the authorities don’t know what to do with me. They have a totally manipulated trial where the court rejected my witnesses. They know that I have the video where the witness points out the manipulation, the promises and the pressure on him to testify against me.

That’s the way things are. I remember a school friend, who loved Cuban literature, who asked me, days before I started to post on my blog, if I was prepared to face the devastating machinery of the system. I was silent for a while. I thought about the urgent need to communicate about my environment and social problems. I replied that I was not naive, that I knew how far they could go, and I remembered Martí and Lorca.

I must admit I never thought the Cuban political police were so twisted. I never imagined I would get involved in such disgraces. Anyway, it’s always one step more to freedom. The desperation of the system is a symptom of fatigue.

Translated by Regina Anavy

Originally published 9 February 2011 – Re-published 12 August 2011

A few days ago, the newspaper Granma announced that by the end of 2011, Cubans would be able to buy and sell homes. Despite the buzz caused by the news – according to the announcement, the steps for conveying property legally would be more flexible – many people still have misgivings.

According to the newspaper, “the payment of the price agreed upon between the parties will be made through a bank branch.”

“I don’t like that. It seems strange that they’re now making it so easy,” says Manolo, 40, who works filling cigarette lighters. He distrusts the requirement to open a cash account at least for the buyer, and adds: “What worries me the most is having to justify the money.”

The government only recognizes as legitimate income from employment, remittances and inheritances. “How do I show the money my brother sends me through ‘mules’ or one of those private agencies that are not recognized by the government?” asks Manolo.

Indeed, for those who can’t certify the legality of their inflows of money, there is the risk of being prosecuted administratively for unjust enrichment, because the state can presume that the deposits are the result of theft, diversion of state resources or activities on the black market.

In these cases, they confiscate homes, cars, bank accounts, etc., acquired over a period of time that may be prior to when the inherited wealth was verified, which allegedly enriched the individual and the close relatives who can’t justify the legal origin of their goods.

Moreover, taxes are also on the list of concerns of those who are obliged to create a bank account to buy a home. The seller must pay personal income tax, while the buyer has to pay for the transfer of property.

And the tax rates make people uneasy. On the black market, real estate is priced in convertible pesos. The price of a stone house with a room, kitchen and bathroom, located on the outskirts, can run between 5,000 and 6,000 dollars in hard currency. In local currency, by which taxes are calculated, it would be between 125,000 and 150,000 Cuban thousand pesos.

The more anxious analyze the situation by comparing it to the taxes on private businesses. “If someone who by the sweat of his work makes more than 50,000 pesos has to pay a 50 percent income tax, can you imagine how much it will be for selling a house?” commented the clerk at a privately-owned cafe.

The transaction, undoubtedly, will eliminate tax evasion, but not fraud in the affidavits. It appears that the relaxation of bureaucratic regulations in the sale of housing will not eliminate “the manifestations of illegality and corruption,” as Granma says. And the government waits.

Translated by Regina Anavy

August 4 2011

The Spanish businessman Sebastián Martínez Ferraté, charged with corruption of minors, pimping and illegal economic activities, will be judged on Monday July 18 at the Provincial Court of Havana, whose official seat is located on Prado, Teniente and Rey. However, trials in the presence of diplomats and the media are usually held in the 10th of October Municipal Court, on Carmen and Juan Delgado.

The Spanish businessman Sebastián Martínez Ferraté, charged with corruption of minors, pimping and illegal economic activities, will be judged on Monday July 18 at the Provincial Court of Havana, whose official seat is located on Prado, Teniente and Rey. However, trials in the presence of diplomats and the media are usually held in the 10th of October Municipal Court, on Carmen and Juan Delgado.

On a ward of La Condesa, a special prison for foreigners on the outskirts of the capital. Martinez Ferraté has been waiting for a year for a trial whose verdict is known beforehand.

The prosecution requested 15 years’ imprisonment, maybe reduced to 10 or 5. But it is clear that they will have him pay the bill for having made, or contributing to making, in 2008, a documentary showing the full extent of prostitution, including child prostitution.

It also exposed the corruption existing around prostitution on the island. The documentary was shown on Tele Cinco, a private TV channel in Spain. It was a blockbuster.

And a blow to the Cuban authorities. So they began plotting their revenge. It is known that every year the US State Department places Cuba on the list of countries where child prostitution is practiced. Something that bothers the government a lot. And the Sebastián case served to send a message to the insolent foreign visitors who might dare to show the ugly face of the country.

The documentary might be new for those who support the Castros in Spain. But for a Cuban independent journalist it is more of the same.

What the audio-visual documents continues to happen in Cuba. Each day the prostitutes are younger and almost an industry of prostitution has been erected. I’m not saying the police stand around with their arms crossed, but for every prostitute, pimp or child molester put behind bars, four more appear.

Prostitution is a social phenomenon. Dragged down by poverty, lack of opportunity and the desire to emigrate, a legion of women sell themselves to tourists for two 20-dollar bills.

The government has never offered an estimate of the number of people enrolled in prostitution. But there are thousands. The public knows about the increase in prostitution and pimping, and they mention it under their breath.

What bothers the authorities is that the subject is being put on display by the mainstream media. And with child prostitution being a sensitive issue, the director of a hotel chain in Mallorca prepared a trap for Ferraté Martinez.

According to the writer Ángel Santiesteban in his blog, The Children that Nobody Wanted, through a Cuban “friend” related to Martinez, in July 2010, they had him come to Cuba believing that he would be making a documentary about the hotel business. No sooner did he arrive in Havana then he was arrested and put into jail.

The Spaniard sinned by naiveté. The Cuban government does not forgive certain “offenses.” They punish them. Harshly. Sebastian Martinez joined the list of guinea pigs that serve the Castro regime for negotiating future deals.

He will become a currency of exchange. Like the American Alan Gross or local dissidents. There are a range of options for exchanging Martinez. From a line of credit, asking the Spanish politicians to raise support for the unique position of the EU, up to silence and complicity with the regime in Havana.Or anything else. You can figure it out.

Translated by Regina Anavy

July 18 2011

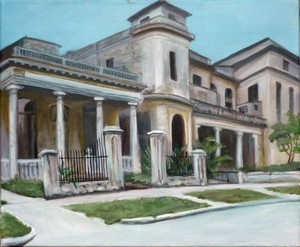

Coppelia, the most famous ice-cream parlor in Havana and in Cuba, turned 45 on June 4. Located on the corner of Calle 23 at L on the central avenue La Rampa, its architecture is one of the most beautiful and best-designed since the olive-green revolution led by Fidel Castro.

The design, by Mario Girona (1924-2008), one of the most important Cuban architects of the 20th century, was done with the collaboration of planners Rita Maria Grau and Candelario Ajuria. The structural calculation was carried out by engineers Maximiliano Isoba and Gonzalo Paz.

Girona formerly completed a successful project baptized with the indigenous name Guamá, established in 1962 in the Zapata Swamp, Bay of Pigs, Matanzas, about 140 kilometers southeast of the capital. Those 10 wooden huts in a circular motion in the manner of a Taino village (aboriginal), on the edge of a lagoon infested with crocodiles, remain one of the favorite places for tourists.

When they entrusted Mario Girona to design the gigantic ice-cream parlor, he was somewhat taken aback. In an interview done a few years ago, he emphasized, “There were no global benchmarks for such an immense ice-cream parlor.” In record time, the architect Girona and his team drew the rough sketch of Coppelia, strongly influenced by the style of the tourist complex of the Zapata Swamp. In this respect he stated: “Guamá was the starting point for the new work. To give some privacy, we designed five small spaces, a large court divided into three sections and a floor on top. We provided ample parking and lush natural vegetation, which would not intrude.”

The hospital Reina Mercedes, built in 1886, formerly was situated on this spot. The land had cost 3,000 pesos. When it was demolished in 1954, the land was worth 250,000 pesos. The idea was to erect a 50-story skyscraper, even taller than the Focsa, the tallest building on the island, with 36 floors.

But the project didn’t materialize because of the arrival of the bearded ones. Before, a recreation center called “Nocturnal” and a tourist pavilion had functioned in the ample space. In 1966, during the celebration of an international congress in the Hotel Habana Libre, situated on the opposite corner, Fidel Castro, a great lover of ice cream, decided to erect Coppelia, whose name and image – the legs of a ballerina – pay homage to one of the great performances of the National Ballet of Cuba.

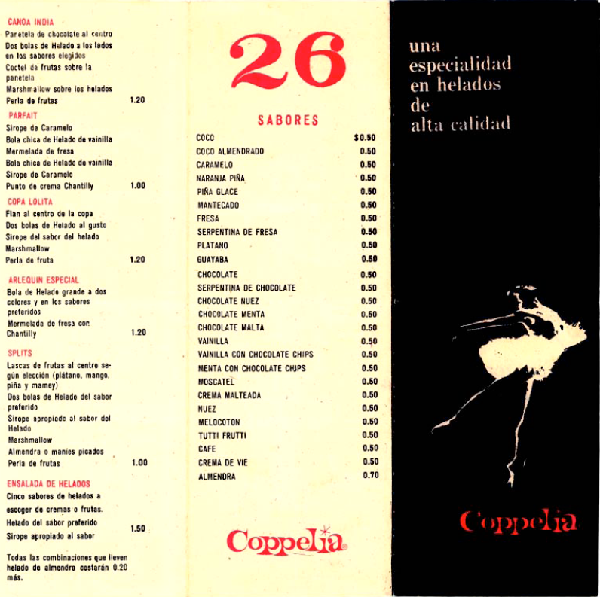

When, on June 4, 1966, the Coppelia ice-cream parlor opened, it offered a menu with 26 flavors and 24 combinations. A scoop of coconut with almonds or cream cost 50 cents, a Copa Melba (vanilla ice cream with a slice of mango, strawberry syrup and marshmallow), one peso. That day they sold more than 3,000 tubs of ice cream, and during the 12 hours it was open, the line was several blocks long.

Ice cream is one of the favorite treats for Cubans of all ages and eras. The first ice-cream shop was installed in 1807. Due to a climate that averages around 30 degrees (Celsius) annually, people like to cool off with ice cream, alone or with cake, cookies and syrup. Or a milk-shake with ice.

Before the comandante took power, there were several prestigious brands of ice cream in Havana: Hatuey, Guarina, San Bernardo and El Gallito. They were sold in ice-cream parlors and cafes or in vehicles located in crowded spots in the city. “I preferred waiting for the seller ringing a bell in a cart with wheels or pulled by horses. For a peseta (20 cents) you could buy an iced coconut,” remembers Humberto, a retired man of 82 years.

Those ice creams, produced with milk in factories, competed with the artisanal fruit ones, produced by the Chinese without milk. According to Josephine, a housewife, 70, “I have never tasted ice cream as rich as the ones made by the Chinese.”

After Castro they continued to make good ice cream. The Coppelia brand was sold in the ice-cream parlor of the same name. It was very creamy and came in 20 different flavors.

With the arrival of the “Special Period,” an economic crisis that has lasted 22 years, ice cream became a luxury. And its quality diminished tremendously. In those hard years, the ice-cream parlor was open two hours a day. There were only two or three flavors, and because of a lack of milk, the ice cream was watery and tasteless.

Ice-cream resellers bought tubs of ice cream from Coppelia. And in their homes or the vicinity of hospitals and playgrounds, they sold a plastic cup of ice cream for 10 pesos. This was one of the many illegal business that existed in Havana.

With the legalization of the dollar, imported ice cream with the brand-names Word or Nestlé arrived. One Nestlé Extreme was worth 2.50 cuc (3 dollars), the 4-day salary of a worker. For hard currency you could also buy first-rate Cuban brands, like Flamingo.

Forty-five years after its opening, the ice-cream parlor Coppelia is only the shadow of its former self. Sunday, May 22, there were only three flavors: vanilla, orange-pineapple and mint. Although ice cream is not expensive, at one peso a scoop (5 cents), its quality leaves much to be desired. Of course, the long lines continue. Once, going to the “Cathedral of Ice Cream” constituted the main week-end outing for many Havana families.

Today, weary travelers, students, workers, prostitutes, pingueros, gays, transvestites and lesbians, among others swarming around the clock by the central ice-cream parlor, form a line by sheer force of habit. There are almost never the flavors you want. Like almond or moscatel. Strawberry or chocolate.

Translated by Regina Anavy

Translated by Regina Anavy

June 4 2011

Although they say abroad that the government of General Raúl Castro is urgently calling for a different period – one that is critical, controversial, appealing and lively – in practice the official reporters are not rushing to drop the burden of language loaded with slogans and pieces from speeches by Fidel Castro.

Although they say abroad that the government of General Raúl Castro is urgently calling for a different period – one that is critical, controversial, appealing and lively – in practice the official reporters are not rushing to drop the burden of language loaded with slogans and pieces from speeches by Fidel Castro.

Journalists working in the state media are thinking twice before producing a hot story containing the reality of the street, which they see in their neighborhoods filled with prostitutes and guys cautiously selling powdered milk, vegetable oil or jeans stolen from some store.

We shouldn’t expect that this bold crowd of “revolutionary journalists,” who look more like scribes or ordinary letter-writers, will decide to write about political aspirations or publicly request the stopping of the acts of repudiation against the Ladies in White and the beatings of those who think differently. It would be asking too much.

The polemical reflections are from a handful of bureaucrats, who, from an office in the Palace of the Revolution, dictate what should be news. For now, it’s possible to transmit these things only on the Web, after passing them through a sieve that shows the editor the authors identify with socialism and are loyal to the Castro brothers. Without that confession of faith, writing for yourself is equivalent to having them open a file on you in the Department of State Security.

There is an open space of criticism and discussion for journalists and intellectuals accepted by the regime, but only on the Internet. They consider it unhealthy or undesirable for Cubans, those who drink breakfast coffee mixed with peas and eat bread without mayonnaise, to be able to read opinions that differ from the official discourse, which is tiresome and repeatedly published by the national newspapers.

The government’s interest is that these talented and fresh writers be read only abroad. So that those who romanticize the Revolution from a distance, and the Latin American and European Left, believe that something on the island is changing.

These inconvenient journalists, who Cubans on the island would like to read in the newspaper, are assigned to publish on personal blogs or websites. Then the guy deep in the Cuban countryside can’t read Elaine Diaz, Sandra Alvarez, Boris Leonardo Caro or gay Paquito, unless he has access to the Intranet.

For people in the real Cuba, lunching on pizzas in self-run cafeterias, after spending two hours at the P-7 bus stop to get home to the Alberro neighborhood, they have no choice but to spend a peso for an 8-page tabloid trying to be a newspaper and usually more useful for wrapping garbage or as a substitute for expensive toilet paper.

Controversy is served up….but exclusively for an elite.

It’s not just Raul Castro’s government that has inconvenient journalists. A sector of the internal opposition also has them. If you’re a foreign correspondent or freelancer and you don’t cover or write a few pages praising some of the events, conferences or projects that the local dissidents invent by the bushel, then they put you on a blacklist.

The least they accuse you of is being a Castro supporter. And in their frequent gatherings in the rooms of their houses, where vulgar dissidents gossip without factual information, you are labeled as an agent of G-2 (State Security).

Doing unfettered journalism in Cuba is like walking a tightrope. It will always awaken the capacity for intrigue and mistrust on both sides. But I prefer it that way. Or I wouldn’t be a journalist.

Translated by Regina Anavy

June 7 2011

Havana is a sort of forbidden city for people from deep inside Cuba. By Decree 217, effective April 22, 1997, residing in the country’s capital is a complicated pattern of bureaucratic procedures and hours of queues at central administration. You have to meet a lot of requirements to be approved to move to the city. It’s a mess.

Unless you’re from Guantánamo, Camaguey or Santiago, and you have some responsibility in a state enterprise or within the Communist Party. Then they open the gates of Havana. And the generous resources of the State or the Party will assure you a dwelling from its vast network of housing for those situations.

If your visit to the capital is temporary, they will put you in a three-star hotel with an open bar, to eat and drink in your spare time. Without spending a cent from your own pocket.

Companies that handle foreign currency such as tourism, civil aviation and telecommunications have homes available to house specialists, engineers or administrative staff from other provinces. Or quality hotel rooms that must be paid in hard currency. It is the only legal way to settle in Havana with the permission of the authorities.

The other is to stay a few days with relatives in the capital, visit the Zoo on Avenue 26, take photos across from the Capitol and visit Chinatown or the beaches of the East. And get the ticket back to the country.

Otherwise, they will open a file on you as an illegal. In pursuit of stopping the growing exodus of Cubans from the country’s interior, desperate because of the acute economic situation and lack of a future. For fourteen years there have been controls and regulations that prevent settling in Havana to those born outside its territory.

They are foreigners in their own homeland. With Decree 217, State institutions pretend to provide a solution to overcrowding in a city that already exceeds two and a half million inhabitants, with a fourth-world infrastructure and a cruel shortage of housing, water and public transport.

There was the paradox that while they tried to stop the terrifying wave, particularly of young people in the eastern regions, who fled their villages to try to live better, they built huts with pitched roofs of asbestos cement, where they housed the builders and the police candidates.

And habaneros don’t want to be cops. Nor do they want to work hard in the construction trades, with low pay and poor working conditions. Thus the government had no choice but to hire labor in the eastern provinces for a period of two to five years.

But the provincial people find a way to leave the plow and the land behind and show up in Havana. There are several reasons. The main one is that in spite of the severe economic crisis affecting Cuba for 22 years, it’s in the capital where money flows, and products and services cost more.

It’s also a good place for girls to take the train from Bayamo or Manatí and prostitute themselves in the streets and bars of the city. There are abundant domestic customers and tourists on the hunt for fresh meat that makes sex pay a good price.

Of course, the hookers from the east of the island are frowned upon by their counterparts in Havana. The prostitutes born in the city consider that the easterners or “Palestinians” as they say, have devalued the longstanding profession, by the low prices they charge. And they hate them.

The easterners who arrive in Havana illegally do everything. From pedaling a bicycle-taxi for 12 hours, to collecting scraps of aluminum or cardboard, selling shoddy textiles, pirated discs, detergents and perfumes on Monte Street.

Those who come to work hard are worthy of admiration and respect. Others, violent scoundrels, want to make money on the fast track. And they become Creole marijuana dealers. Or pimps who get off at the railway terminal with a harem of hookers, disoriented with the lights, and put them to work in dilapidated rooms, screwing for 5 dollars a half-hour.

From El Cobre or Manzanillo, gays and lesbians are also packing their bags, coming from villages where they are frowned upon and kept in the closet. Once in the capital, they quickly adjust to the dissipated nightlife. With high heels, transvestites attend the gay or lesbian parties, without the disapproving gaze of family and friends.

It often happens that sometimes the police are from the same province, but this does not affect them. They hunt and then ride the train back in the morning. In vain. Because the illegals, marginalized by their sexual orientation, manage to evade the police cordon and controls. And they return to Havana. It’s a matter of survival.

Translated by Regina Anavy

June 14 2011