![]() 14ymedio, Zunilda Mata, Havana, August 4, 2019 — “This was one of the places where more people joined,” remembers Loipa, a resident of Malecón and Escobar in Central Havana. Twenty-five years after the Maleconazo*, the events of that day have taken the form of an urban legend that older people tell and younger ones don’t know. “That fifth of August in 1994 it seemed that everything was ending,” stresses the woman.

14ymedio, Zunilda Mata, Havana, August 4, 2019 — “This was one of the places where more people joined,” remembers Loipa, a resident of Malecón and Escobar in Central Havana. Twenty-five years after the Maleconazo*, the events of that day have taken the form of an urban legend that older people tell and younger ones don’t know. “That fifth of August in 1994 it seemed that everything was ending,” stresses the woman.

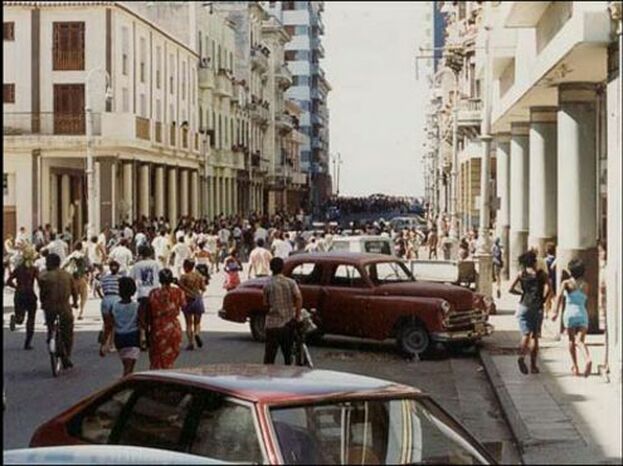

The area has changed a lot since that social explosion that put Fidel Castro on the ropes. Calle San Lázaro near Maceo Park now has a quarter century more of deterioration, in several places entire buildings have collapsed, and “the majority of those who experienced that moment have left or have died,” says Loipa.

“I was a nurse at Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital when everything happened,” she remembers of that Friday. “We started the day with no light and I didn’t have to work that day but I had gone out to look for some food because in the house we’d gone a week with only rice and a sauce that my mom invented with lemongrass and oregano from the ground.”

The crisis, which the government had baptized with the euphemism of Special Period, had been dragging on the lives of Cubans for several years. After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the economy of the Island sank from the lack of fuel, the abrupt cutting of imports, and the lost of Soviet support that turned out “brutal,” according to the economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago.

That fifth of August, Loipa was unaware of what was brewing near her house. For days tension had been growing after authorities intercepted several boats sailing toward the coast of the United States. A rumor began to gain force on the street: that the Government was going to permit the arrival of boats from Florida to seek family members on the Island, just as had been done in 1980 during the exodus of the Mariel Boatlift.

“That morning my son came in the house and told us he was going,” remembers Fernando Soriano, a retiree who lives in a neighborhood “with a view of the sea,” as he likes to call it. On the avenue of Malecón and near the corner with Campanario, the now retired man is in the business of collecting beer and soda cans from businesses in the area to sell them in raw material centers and augment his pension.

A few months earlier, in an attempt to relieve the social pressure cooker, Castro had promoted self-employed work by permitting some licenses for the private sector. Thus were born the first private restaurants, the first small shops in decades that sold sweets, fried food, and pizzas in a legal manner, but the economic situation remained at rock bottom for the great majority of Cubans, trapped in a suffocating cycle of survival.

“Many people like my son went to the boat launch on the Regla wharf to see if they could go on the boats that were going to arrive,” remembers Soriano. “That filled up but the police already had surrounded the place because the residents of this area kept going down through all the streets to get to the Malecón wall in case the boats came.” In one moment the frustration erupted.

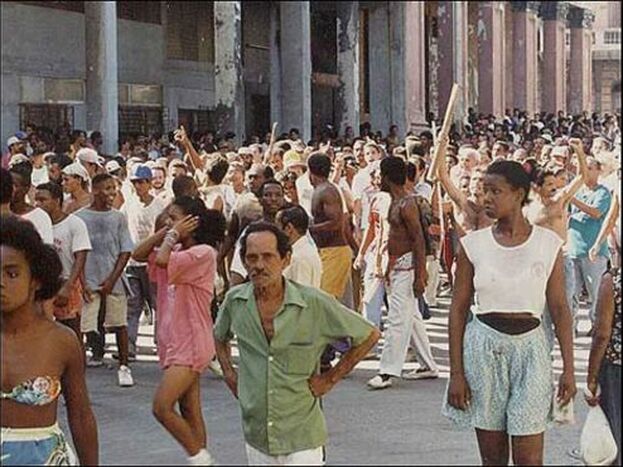

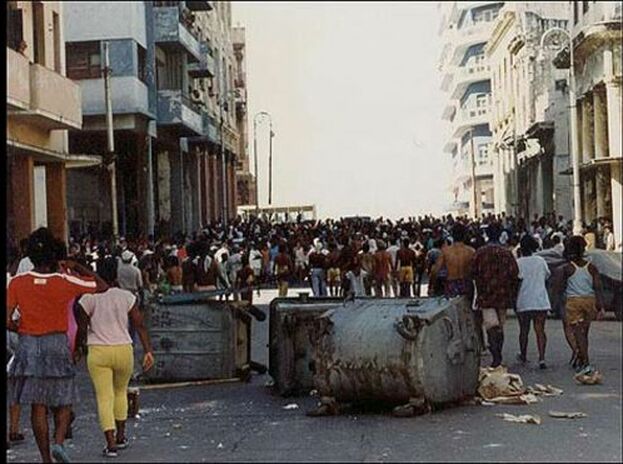

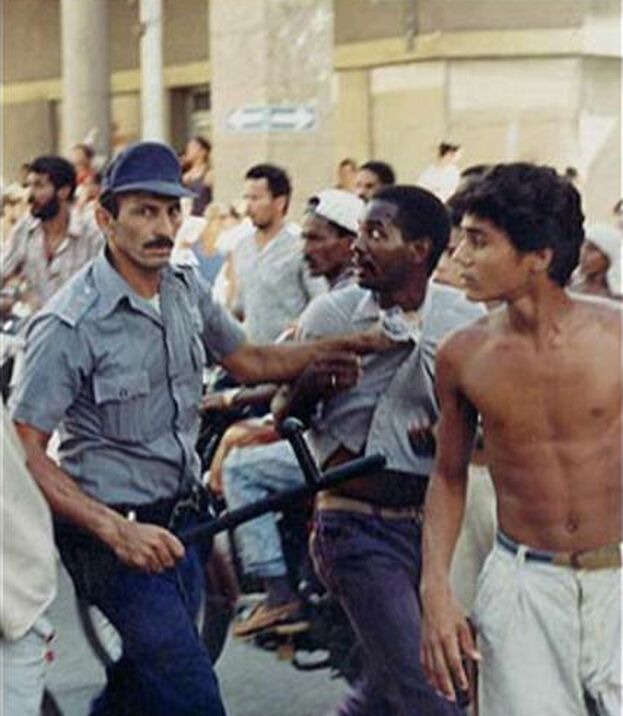

“The Malecón turned into a death trap, when the people came to realize that they weren’t going to let them go, the shock troops were already here,” he explains. Soriano points out the intersection of Calle San Lázaro and Belascoaín. “The Blas Roca construction contingent entered through here, with helmets and rebar in their hands, dealing out blows on all sides.”

Soriano believes that the protest didn’t turn into more because “it lacked leadership and they chose the route poorly.” He believes that “had they placed themselves in Central Havana and Old Havana and moved outward, thousands of people would have joined and then everything would have been different because it’s not the same thing to suppress a handful versus a sea of people.”

Castro had the skill of setting civilians against each other to avoid the image of uniformed soldiers hitting the population. “No one knew who was who, although I remember that those who were demonstrating looked skinnier and with more raggedy clothing,” says this Havanan.

Mesa-Lago believes that the worst year of the crisis that led to the Maleconazo was 1993, “but the crisis began in 1991,” he specifies. What was lost was not a small thing, between 1960 and 1990 the USSR injected around $65 billion into the Island’s economy. In the decade of the 80s that bulky subsidy generated a “golden” age of Cuban socialism that some still remember today with nostalgia.

Ernesto was born a year after that popular revolt and now he operates a pedicab in the vicinity of where on that day his father joined a group of those who were yelling and demanding that they be permitted to leave the country. “The old man has told me some things but he doesn’t like to talk about that day because the police arrested him and put him in jail.” Years later and after leaving prison, Ernesto’s father managed to get political asylum in the United States.

“Here almost nobody talks about that, although everyone still has the same desperation to leave,” reflects the bicycle-taxi driver. “People no longer go out in the street [to protest] because it was already seen that nothing is achieved, but the Maleconazo of today is outside of the embassies,” he believes. The event has been erased from official history and every August, the media praises the birthday of Fidel Castro, on the 13th, while they silence that other day that marked so many lives.

The Rafter Crisis [Crisis de los Balseros] that erupted after, in which tens of thousands of Cubans embarked upon the sea, has also been erased from the anniversaries that are studied in schools and broadcast on national media.

On the same corner of Malecón y Belascoaín, one of the epicenters of the protest, now there is an esplanade where children play and at night groups of young people gather to share their dreams and a lot of rum. The adjacent building has some columns that look out on the sea, they have tried to hide the cracks with some paint.

A man rocks in a chair in the doorway while he sells paper cones of peanuts. He says that he doesn’t remember much of that day but that in the stairway of the entrance of the building “some children hid, one of them covered in blood because they had split his head.” The neighborhood of San Leopoldo, in Central Havana, was one of those that took the worst part of the suppression against the demonstrators on that fifth of August.

Propelled by frustration and rage, some of them began to break the glass windows of state-owned businesses and vandalize trash containers. “Here almost every family had a child beaten that day or who later left on a raft,” believes Soriano.

Official media broadcast the arrival of Fidel Castro to the area, like a sign that the revolt had been pacified and the Government had emerged victorious. “He only arrived when everything was already calm and the truth is that that wasn’t a happy day for anybody in this neighborhood,” says a resident of San Leopoldo who prefers anonymity and who was surprised by “all that” on the street.

But behind the official silence, the wound remains open. “I handed in my Communisty Party card a little after that, I had stopped believing in everything when I saw the builders splitting heads open and dealing out blows,” the woman makes clear.

*Translator’s note: In Spanish “azo” is an ending used to coin words and implies concepts such as “blow and hit, and also big.” In this case, added to “Malecon” it means the explosion/riot on the Malecon.

Translated by: Sheilagh Herrera

____________________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.