One way or another, the street protests taking place recently in Venezuela are being noticed in Cuba. The most nervous are the olive green autocrats.

According to a low-ranking party official, since the death of Hugo Chavez, the regime has had several contingency plans in its drawer, in case the situation in Venezuela were not favorable to the interests of the Island.

“If Maduro falls there exists a plan B. In the corridors, at least at the level where I work, it was assumed that Maduro might be a president with a fleeting career. Although the PSUV (United Socialist Party of Venezuela) has controlled a large number of the threads of power, there are divergent opinions among the Chavez followers themselves about the relationship of their country with Cuba. This kind of socialism, with democratic streaks, is not reliable. Maduro might lose power either by a recall referendum or within six years. In meetings of our nucleus it is commented that Maduro’s term in office only serves to buy time,” the official notes.

The earthquake of marches, barricades and opposition protests shocks different regions of Venezuela, but the epicenter shakes the corridors of power in Cuba.

The Castro brothers risk a lot in Caracas. Just in case, Raul Castro opened a window to Brazil in the new Mariel Port and Special Development Zone with a different jurisdiction.

And he almost begs the United States, his number one enemy, to sit down and negotiate. Meanwhile, the Castro diplomacy travels Florida, trying to seduce the wealthiest businessmen of Cuban origin. Although sensible businessmen would keep thinking. When they look at the recent past, they only see shady dealings and a cryptic partner who at the first exchange transforms the rules of the game. Therefore, the Caribbean autocracy is going to have to fight dog-faced and with gritted teeth its strategic position in Venezuela.

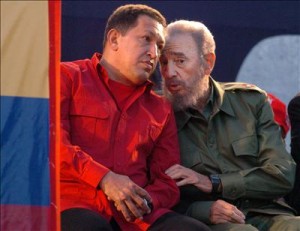

The key, you know, is oil. 100 thousand barrels daily acquired at a bargain price so that Cubans do not suffer outages 12 hours a day. When the paratrooper of Barinas (Hugo Chavez) arrived at Miraflores in 1998, Fidel Castro understood that after nine years of crossing through the desert, with finances in the red and exotic illnesses devastating the country, the hour of his resurrection had arrived.

Cuba entered the light phase of the Special Period. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the country continued in a fixed economic crisis, but the loyal Bolivarian shared his strongbox. And it was an important piece of the anti-imperialist project that so excited the commander.

The death of Chavez was the beginning of the end of the honeymoon. Maduro is loyal and is allowed to drive. But he does not have charisma. And after 14 years of foolish economics in pursuit of gaining followers among the most disadvantaged, the debts, violence and inflation have exploded in the face of the PSUV.

Maduro, stubborn and awkward, instead of releasing the uncomfortable and parasitic ballast of Cuba, to govern for all and look more to Lula and Dilma than to the Castros, moved his pieces incorrectly.

He tried to continue the Joropo and the booze party of comrade Chavez. He designed a simple strategy: he shouldered his comrade’s coffin and tries to govern in his name.

And it is failing. In Cuba, because of selfishness or a short term mentality, the ordinary people, tired from 55 years of disasters, cross their fingers and hope that the Venezuelan crisis does not close the oil spigot opened by PDVSA (Venezuela’s state-owned oil and gas company).

In a park in the Havana neighborhood of Vibora, several retired people opine about the situation in Venezuela. “If that is screwed, what happens to us is going to be huge. The blackouts will return, industry will be paralyzed again and we will return to a phase the same as or worse than the beginning of the Special Period in 1990,” says a man of about 70 years of age.

Others are less pessimistic. “It’s true, it will be hard. Since the revolution triuimphed we have been accustomed to living at the expense of foreign sweat. Before it was the USSR, now Venezuela. If the worst happens there, here reforms will accelerate. Although this is already capitalism, but with low salaries,” points out a woman who identifies herself as a housewife.

A university student adds to the conversation. “Seeing the marches or strikes on television is something that I envy. That freedom of protesting in front of the governmental institutions, as in Ukraine or Venezuela, we need it in Cuba.” And he adds that “in the meetings of the FEU (Federated University Students), the situation in Venezuela is a top priority topic, but I have heard rumors that in some Party cores the alarm is greater.”

In this warm February, in spite of the news that arrives from Caracas, the ordinary people continue on their own. Standing in long lines to buy potatoes that have disappeared. Going to farmer’s markets in search of other tubers, vegetables and fruits. Or sitting down at the neighborhood corner to talk about movies, fashion, soccer or baseball.

And so it is that for many on the Island, Venezuela is not on their agenda.

Diario de Cuba, 23 February 2014, Ivan Garcia, Havana

Translated by mlk.