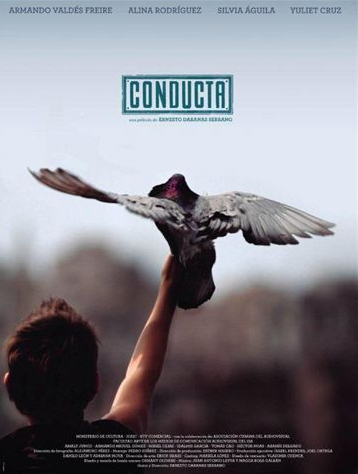

Miguel has earned a lot of money this week. He managed to sell almost one hundred pirated copies of the Cuban movie Conduct. Although the film is showing in several of the country’s theaters, many prefer to see it at home among friends and family. The story of a boy nicknamed Chala and his teacher Carmela is causing a furor and leading to long lines outside the premiere cinemas. It’s been decades since any national production has been so popular or provoked so many opinions.

Miguel has earned a lot of money this week. He managed to sell almost one hundred pirated copies of the Cuban movie Conduct. Although the film is showing in several of the country’s theaters, many prefer to see it at home among friends and family. The story of a boy nicknamed Chala and his teacher Carmela is causing a furor and leading to long lines outside the premiere cinemas. It’s been decades since any national production has been so popular or provoked so many opinions.

Why is the latest creation of director Ernesto Daranas becoming such a social phenomenon? The answer transcends artistic questions to delve into the depth of his dreams. While it is clearly told with excellent cinematography and superb acting, its the realism of the script that is the greatest achievement of this film. The movie generates an immediate rapport with the audience, reflecting their own lives as if reflected in a mirror.

In the dark theaters, facing the screen, the spectators applaud, scream and cry. The moments of greatest emotion from the house seats coincide with the politically most critical speeches. “No more years than those who govern us,” answers the teacher Carmela when they want her to retire because she’s spent too much time in the teaching profession; an ovation of support runs through the theater at that instant. The semi-darkness exacerbates the audacity and complicity.

The “Conduct phenomenon” is explained by its ability to reflect the existence of many Cubans. But it goes far beyond a simple realistic portrait, to become an x-ray that lays bare the bones. A Cuba where there is hardly any moral framework left for a child in this environment light-years away from the ideal claimed by the official media. Barely twelve, Chala supports his alcoholic mother with what he earns from illegal dog fights, inhabiting a harsh unjust city, impoverished to the point of tears.

It’s not the first time Cuban cinema has shown the tough side of reality. The film Strawberry and Chocolate (1993) paved the way for social criticism, particularly with regards the discrimination against homosexuals and artistic censorship. The cost of its daring was high, because it had to wait twenty years to be shown on national TV. Alice in Wonderland (1991) faced a worse fate, with the political police filling the theaters where it was projected, and party militants screaming insults at the screen. Conduct has arrived in at different juncture.

The spread of new technologies has allowed many filmmakers to find ways to make their projects. Critical, acerbic and rebellious scripts have seen the light in the last five years because they have no need for the approval and resources from the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC ). This proliferation of shorts, documentaries, and independent films has been a very favorable situation for Ernesto Daranas’ filmstrip. The censors know that it’s not worth the trouble to veto such a movie on the State circuits. It would run through the illegal networks like wildfire.

A brief conversation outside the Yara cinema exposed the controversy this story unleashed. “There are a lot of people who live better than Chala, that’s true, but there are others who live much worse,” said a man in his sixties. A young woman responded that she wondered if the director ”exaggerated the squalor of the situations shown.” Another girl joined the debate to say, “You say this because you live in Miramar, where these things don’t happen. ”

On Tuesday night, the ruling party journalist Randy Alonso also joined the line to see the movie in the final showing of the day. Behind him giggles and comments were heard — “So what’s he doing here?” — given that his face is associated with uncritical journalism, a sycophant of power. Once inside the theater, those who sat near him did not see him join the chorus of shouts of support. With every minute that passed, he seemed to sink more deeply into his seat, not wanting to be noticed. What he was seeing on the screen was the exact opposite of what he explains on his boring Roundtable show.

So it is that Conduct was able to gather in the same room the fabricators of the myth and those burdened by it. After the projector is turned off, the doors open and the viewers exit to reality similar to the script, but one where they can no longer express themselves under the protection of the shadows. Chala waits for them on every corner.

21 February 2014