Cubanet, Rafael Alcides, Havana, 13 January 2015 — Following the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the United States, Havana has become a cauldron of ideas about how we could have elections by secret and direct ballot – an exciting thing to contemplate. Many here see it happening right around the corner, maybe within a few years, three at the most. Others completely deny it. They speak – not in favor, but they do speak – of the Chinese method as the successor to Raul Castro socialism.

Cubanet, Rafael Alcides, Havana, 13 January 2015 — Following the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the United States, Havana has become a cauldron of ideas about how we could have elections by secret and direct ballot – an exciting thing to contemplate. Many here see it happening right around the corner, maybe within a few years, three at the most. Others completely deny it. They speak – not in favor, but they do speak – of the Chinese method as the successor to Raul Castro socialism.

Would the Communist Party participate in such elections? This is one of the topics for debate. Some would prefer not to even hear of this. Others – myself included – believe that it would be impossible to exclude the Party: because we are democrats, because otherwise the elections would be invalid, and because, still, the Communist Party holds the reins of power.

However, upon the new government’s establishment, there would be a movement to seize and recover all of the Party’s properties. All. That means, guest houses continue reading

The consensus appears to be unanimous to prevent the current leaders from occupying public positions in the new government. Well, now, would these personages, civilian or military, have the right to run for office? There is no agreement about this, but based on what I have been able to detect from conversations on the street, the public for the most part does not see a reason to oppose this.

There is even talk of a Senator Mariela Castro and a Mayor Eusebio Leal. I do not doubt that they would win. With the appropriate official support, of course, Ms. Mariela Castro Espín has done commendable work—work that in no way diminishes the historical responsibility of her relatives in creating the tragic UMAPs—and this work has gained her a place in the social struggles of her country.

For his part, Eusebio Leal – “St. Eusebio,” as some call him — has shown how much can be done, even without plenipotentiary powers, for a city. Understandably, one hears talk of forgetting the air-kisses which the Maximum Leader, during his speeches, would covertly or overtly blow to Leal. That was, they say, the price the saint had to pay – but thanks to him, they also say – Old Havana exists today. Therefore, generally speaking, the future “dream” electorate of Havana exists because of Eusebio. And because of Mariela.

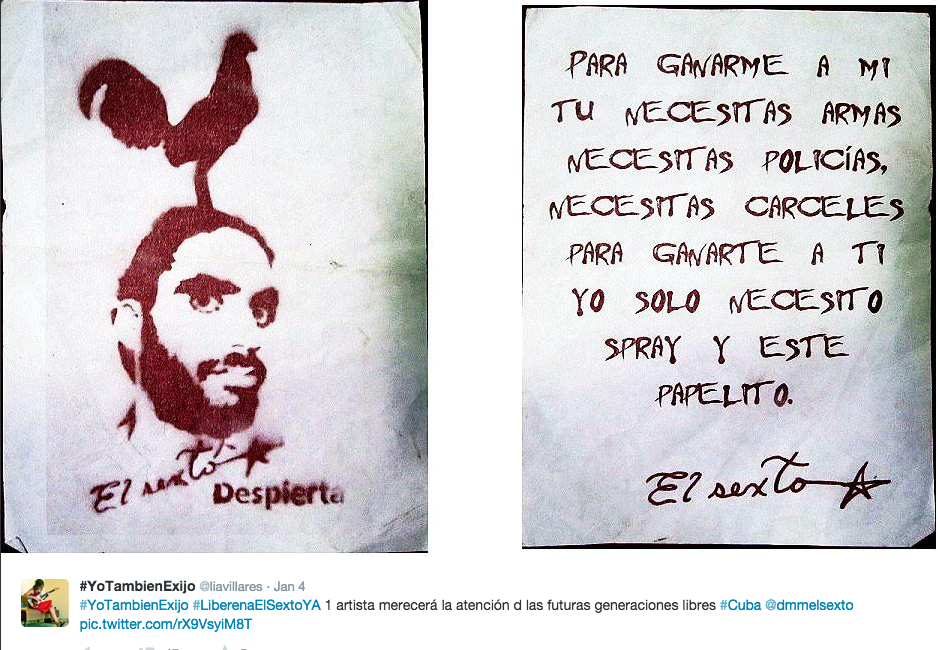

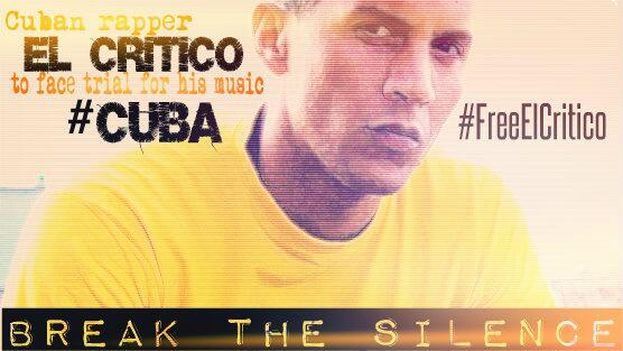

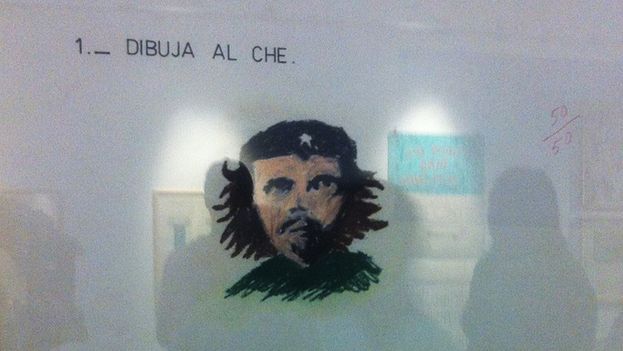

Well, now, what of the non-recycled candidates, i.e. the new blood, the candidates of the democracy? There lies the great unknown of the moment, the question without an answer among those who already see themselves before the ballot boxes, flags flapping away in the city covered in leaflets and palm leaves. Because they have had no place in the public life of the country, the dissident leaders are not known by the public. The government has never mentioned them – not during their almost-daily detentions, nor upon their releases. Prematurely aged as they enter and leave the jails, and well-known abroad; but in their own country the dissidents are no more, at most, than names heard in passing.

But, fine – it is said – the candidates will appear, the important thing is that elections are around the corner. In the organizing process of the parties, the fighters of old and the new ones, the ones yet to appear, will be known. Upon uttering these words the future elector is seen to sigh and assume an expression of, “Finally! At last! We will have a President and Congress that emanate from the will of the people.”

It is a joy not without its worries. Will free education and hospital care disappear with a democratic government? Here starts the guessing once again. Will the house one lives in have to be returned to its former owner? What about the plot of land granted by the government? As the Russians did, will the current rulers retain the enterprises created by the socialist State?

All of this is fodder for discussions on the street corners, but the joy is so great at even talking about democracy that the conversation veers again towards elections and the media that will facilitate them: radio, TV, the printing of leaflets, etc.

Nevertheless, those who had already been planning to leave the country are still packing their suitcases. And, those who claim to know very well that what is really coming is the Chinese method, sorrowfully spit through their fangs. Raúl and his generals are uninterested in hearing talk about these things, they say. Elections?? And they point to the recent events concerning the artist, Tania Bruguera.

Ultimately, whether these killjoys are right or not, Hope has come knocking, and it is impossible not to let her in.

Translated by Alicia Barraqué Ellison