![]() 14ymedio, Mario Penton, Miami, 7 December 2017 — Ernesto Machado will never forget a cold morning in 1968 at José Martí airport in Havana. A migration officer removed her parents’ gold wedding rings while annulling her passport. “This is the property of the revolutionary government,” the woman dressed as a soldier told her, before she left Cuba to never return.

14ymedio, Mario Penton, Miami, 7 December 2017 — Ernesto Machado will never forget a cold morning in 1968 at José Martí airport in Havana. A migration officer removed her parents’ gold wedding rings while annulling her passport. “This is the property of the revolutionary government,” the woman dressed as a soldier told her, before she left Cuba to never return.

On coming to power in 1959, Fidel Castro’s government imposed severe measures to prevent money and valuable goods from leaving the country. Almost sixty years later, although the international situation is different, the customs controls remain rigorous on this issue.

“I travel to Cuba every 15 days and I take medicines, food and money to any part of the island,” says a Cuban who resides in Miami, whom we will call Juan to protect his identity. continue reading

“Everyone wins with this business, the person, because he goes to Cuba to see his family members or, if he lives on the island, he gets a little trip, and the agency because that is our business, sending things and money to the island,” he explains

In the case of money, an agency like Juan’s can charge up to 6% commission on amounts over 20,000 US dollars. He says that he makes several shipments a month because “there are many people buying properties in Cuba.” Areas like Old Havana and Miramar are quoting very well, he says.

On revolico.com, the largest online sales platform on the island, houses sell for from 10,000 or 20,000 dollars in popular areas, and for up to $270,000 in the Havana neighborhoods of Miramar and Siboney or in the colonial city of Trinidad.

Cuban laws stipulate that you can freely import up to 5,000 US dollars per person and that for larger amounts you must fill out a declaration in Customs, without this necessarily requiring the payment of taxes. In most countries you can import up to 10,000 dollars without having to give a statement.

Juan does not care about the origin of the money he sends to Cuba nor does he follow the mechanisms to declare that cash in Miami or Havana. “Normally we send it with several people, we distribute the money to stay under the $5,000 barrier, and sometimes I send some trusted person to take in a little more, taking a risk, of course,” he says.

A report published in the official press reported that, so far this year, the General Customs of the Republic has registered 384 violations of the entry and exit of foreign exchange.

The newspaper recounts some of the cases, like a woman who hid 5,000 Swiss francs in condoms inserted in her vagina, or a man who had 32,550 euros tied to his body.

“Many are beginners in this business or try to do things without helping others, you have to live and let live,” says Juan, who according to his own testimony frequently bribes customs officials.

“I have been in business for a long time, my people are always known because we share codes. Usually when someone arrives at the airport, they offer to help you and if you accept it, things will always go well for you,” he says.

“In Cuba, there are businesses that need to take money out of the country. It’s a secret to no one that most of the products bought by the paladares [private restaurants] come from the black market. If the owners fall [in a police operation] they want to have a little piece of land on the other side, to keep something,” he explains.

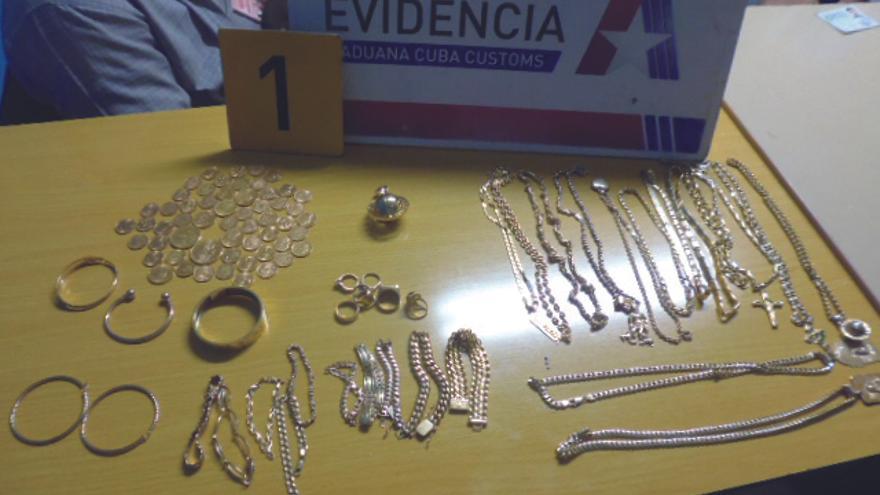

According to official data, this year Customs has seized 165,816 CUC (Cuban convertible pesos), 61,660 CUP (Cuban pesos), 875 euros, 15,150 rubles, 73,822 dollars and 386 valuables (crucifixes, coins and silver bars), which travelers were trying to get out of the country.

The Central Bank of Cuba (BCC) allows each person to freely take up to 5,000 dollars out of the country. For higher amounts, an authorization from the President of the BCC is needed after verifying that the money has been lawfully earned on the island.

Buying foreign currencies inside Cuba before traveling abroad is a complicated task, although the law allows it. The banks require the customer to show a visa and an airline ticket linked to the country of the requested currency and, even so, only small amounts of foreign currency are sold.

You can always resort to the informal market but there the dollar is sold at a price that ranges between 92 and 97 cents in CUC, well above the official rate of 87 cents. On the other hand, it is strictly forbidden to remove from the country any amount of CUCs, the so-called convertible peso, which in fact has no value outside the island. The Cuban peso also has no value abroad, but it is possible to take out up to 2,000 CUP.

A few weeks ago, the American blogger Jaime Morrison, travel correspondent for BravoTV’s digital site, was arrested by the Cuban authorities, who confiscated the approximately 800 CUC he was carrying when he was about to leave the country.

“I broke this rule and I almost got sent to jail, do not let it happen to you,” the journalist said, telling the story about her experience in Havana. After a long interrogation she was able to leave the country, but without the chavitos.

___________________

The 14ymedio team is committed to serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time by becoming a member of 14ymedio. Together we can continue to transform journalism in Cuba.