This is the third and final part of the testimony of a Cuban who has made the dangerous trip from Guatemala to the United State. Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here.

![]() 14ymedio, Mario J. Penton, Mexico City/Laredo Texas, 20 November 2015 – The smell of coffee draws me to the kitchen. The first rays of the sun have yet to appear when Domitila and her husband Juan get ready to start work on the farm. They protect us that day, hiding us from the Mexican police, always ready for deportations. “There have been hundreds, if not thousands, of Cubans who have passed through this house. They all say the same thing, ‘You can’t work there, you can’t live there’,” they say.

14ymedio, Mario J. Penton, Mexico City/Laredo Texas, 20 November 2015 – The smell of coffee draws me to the kitchen. The first rays of the sun have yet to appear when Domitila and her husband Juan get ready to start work on the farm. They protect us that day, hiding us from the Mexican police, always ready for deportations. “There have been hundreds, if not thousands, of Cubans who have passed through this house. They all say the same thing, ‘You can’t work there, you can’t live there’,” they say.

“Thanks to the Cubans we have this little ranch.” Their house barely has two rooms, one of which our group of immigrants is occupying. The family treasure is their farm, a little expanse of land with rubber trees. In this place we received the best care of the whole journey, we even get a bath.

A special solidarity joins this noble-hearted woman with the fate of Cuban migrants. Her daughter has lived in the United States for ten years. She arrived there as a ‘wetback’ and since then they haven’t seen each other. This was our last stage towards Mexico City. continue reading

A cold wind, in keeping with the altitude, and the endless lights leads us to believe we have arrived at the capital. The danger of a special police checkpoint makes us throw ourselves from the truck as fast as we can and take off into the semi-desert. The guide hurries us. Again, an altercation with the tropical version of the “revolutionary tough guy” is about to get us deported. The intervention of women prevents a river of blood, at least for the moment. The night passes without other mishaps.

To the joy of some and sadness of others, tonight is the last time we see the Hindus and the Central Americans. Halfway along the road a vehicle intercepted us, they climbed on and quickly took another route. According to what they tell us, they will enter at another border crossing.

We meet the “patroness,” a lady with the credentials of a trafficker who combines, in her features, virility with cunning and the female sixth sense

We arrived in Mexico City at three in the morning. A beautifully designed house, full of artworks and books of literature, religion and history suggest to us that we are in contact with someone knowledgeable and sensitive to the world of culture. Meeting the “patroness” is a huge surprise, a lady with the credentials of a trafficker who combines, in her features, virility with cunning and the female sixth sense.

“One Cuban who is coming alone!” Timidly I raise my hand. “Another!” A boy from the group joins me. “Another Cuban who is coming alone!” she says imperiously. “You! Get up, let’s go!” Maikel is traveling with his uncle, but his pleas are useless. It is decided and there is no turning back. He will have to leave his uncle alone.

The Cuban “tough guy,” who tried to sneak into this first departure, ended up with his tail between his legs on learning that even though he had given his wife’s jewels to the coyote in Guatemala, supposedly his money is not enough and he will have to wait in Mexico. We immediately think that this is the response of the organization to the aggressive attitude of the guide who took us to the capital.

After breakfast they lead us to a trailer. On the way I confirm my suspicions: the “patroness” is a woman of exceptional intelligence. Easy conversation and well-formed opinions, who holds forth fluently about the Mexican reality. She has dedicated her life to study, is not married and her main hobby is travel, such that in her 40 short years she knows well a good part of the world, including Cuba. After wishing us the best part of the journey, she makes us appreciate the privilege bestowed by the Cuban Adjustment Act and asks us to take advantage of this opportunity to improve ourselves and become good men.

The truck driver is also easygoing. His name is Oscar. He has spent many years transferring goods to the United States border. Although he is forced to smuggle Cubans to support his family, according to what he tells us, it has never entered his head to emigrate to the United States. With the money he makes, he “scrapes by” he tells us.

For nearly fifteen hours we are locked in that trailer, in places specially designed to hide people. Tiny little spaces we have to get into at every checkpoint that trips us up along the way, although, according to what Oscar says, everyone is paid.

“Corruption is the cancer that afflicts Mexico,” complains Oscar, “but we are all corrupt because the politicians themselves are the first in corruption and enrich themselves at the expense of the country.” While he traffics with three little Cubans towards the neighbor to the north, the generals, he thinks, do the same with arms and drugs. Everyone is involved, just at a different scale.

A white pick-up controlled by the fearsome Zetas is charged with getting us to the border. The trafficking ends with them, because they are the ones who control the underworld of the border area.

In Nuevo Laredo the border crossing is organized. A white pick-up controlled by the fearsome Zetas is charged with getting us to the border. The trafficking ends with them, because they are the ones who control the underworld of the border area. They tell us to leave everything we have, that is, barely a bag with a change of clothes that we carry hidden. Supposedly we should arrive at the international bridge to Laredo, Texas, with nothing, so as not to raise the suspicions of the Mexican police. After an exchange of words with our dealers, I manage to save the papers that testify to my university degree and a Cuban flag. All the rest is left in the past. They give us four Mexican pesos, with which we begin a new life. Before us, the bridge that marks the end of a life without rights.

Nothing compares with the thrill of feeling free. Holding back the tears, we advance as fast as possible to reach the other shore. The nightmare is over. Jungles, swamps, police, the fear of an assault, narcos, traffickers, all is left behind like the price to be paid for freedom.

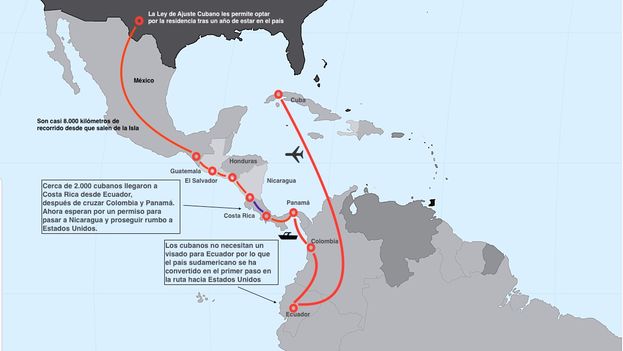

A group of around 80 Cubans is spending the night at the US immigration facilities, which are overflowing with the flood of Cubans. Some have been waiting days to process their paperwork. Not all of them arrive for political reasons. Many comment that their intention is to return to Cuba as soon as they obtain US residency. They left Cuba, selling their homes or going into debt, via Ecuador for two basic reasons: desperation in the face of a situation with no outlet, and fear of losing the privileges awarded by the Cuban Adjustment Act, with the recent openings toward the regime in Havana.

They have never heard about any rights and they don’t know what democracy is.

It is a time to give thanks, for us to rejoice on reaching the land of freedom. Also a time to mourn for those who did not make it. We have crossed our on Red Sea, and now the task before us is not to long for the onions of Egypt, although what lies ahead is the desert that faces every migrant.

We can finally say, like José Martí: “Freedom is expensive and you have to decide to pay its price or resign yourself to living without it.”