When I read the latest episode of Eduardo del Llano, with his movie “Vinci” not being admitted into the upcoming International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana, I can’t escape the memory of a charming passage in my short history as a television writer.

When I read the latest episode of Eduardo del Llano, with his movie “Vinci” not being admitted into the upcoming International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana, I can’t escape the memory of a charming passage in my short history as a television writer.

It occurred to us, the producers of a television program devoted to the cinema in my eastern city, to develop a hideous scaremongering project like that “300” based on the comic by Frank Miller. The idea was to break it down into an introduction with historical analysis that the film didn’t even come close to achieving.

Never, despite the television film questioners in the national totalitarian basement, were we censored. Later we understood: our proposals were too elevated for the coefficient of our censors.

However, just on the Sunday night that “300″ was to show on television in Bayamo, Cuba, the TV station phone received the order from the Provincial Party: we could not put that movie on the air.

The reason? A cultural censor diligently read a review in the newspaper Granma that night, which accused “300″ of being a manipulation of Hollywood against the Persians, great-great-grandparents of the current subjects of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. No, definitely not: forbidden to play the Imperialists’ game against our Iranian brothers.

I think of that, inevitably, after reading the argument under which “Vinci”, the prime cinematographic work of the ingenious Eduardo del Llano, was rejected by the “Selection Committee” (cacophony please) of the New Latin American Film Festival of Havana.

We can summarize the little letter in a sentence: the film was not accepted because it did not address a Latin American theme.

Yes, Edward is as Latin America as the warm Havana walls he lives between, his film is as Latin American as any production of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC), but his work — horrors! — dared to look at universality from an imaginary passage in the life of Leonardo da Vinci’s genius, and the “Selection Committee,” world map in hand, knows that “that is not in Latin America.”

Ah … what a delicious passage. What a play of ironies: the director of the series of shorts featuring Nicanor O’Donnell (Luis Alberto Garcia), suddenly discovers he is starring in one of the amazing absurdities that fill his shorts.

Because the thread that ties the censorship of that gimmicky and mediocre movie we wanted to show and dissect for the public of my city, and this censorship with kid gloves that is now applied to Del Llano with his filmstrip, we could define it using a most delicious Creoleism: intellectual guajirismo.

It has political overtones in some cases, nationalist undertones in others, but has the same plinth at the level of the brain: guajirismo of the intellect.

Guajirismo is not a human condition or an accident of geography. It is primarily a projection of thought. Although the term is derived from the word “peasant” as applied to Cuban farmers, and by extension to any Cuban who is not born in Havana, I think the definition of peasants portrays the sort of intellectual closed-mindedness, ridiculous chauvinism, that certain intellectual circles in Latin America and in Cuba – where else? – are suffering from and where they reach their sovereign consummation.

It’s about a mental deformation so rotten with patriot-ismos, provincial-ismos, of values in the name of some supreme commander who doesn’t know what “must be defended,” which can be nothing less than to be abhorred by those who have true art.

In 2008, a Peruvian whose shadow is worth more than all the intellectual guajiro, Francisco Lombardi (responsible for some of the most memorable American films of recent years), was the President of the Jury of the same festival in Havana. I will never forget the bitter words in an interview with which he defined, for me, much of the film production that was done in the region, “An art that looks at its navel, an art for four brainy supposedly applauding spectators at a provincial hall.”

Unfortunately for Eduardo del Llano, his “Vinci” did not want to recreate the drama of a mining family in Bolivia, nor of the massacres of drug traffickers in Mexico, nor the Central American migration, nor was it a patriotic denunciation of the British presence in the Falklands.

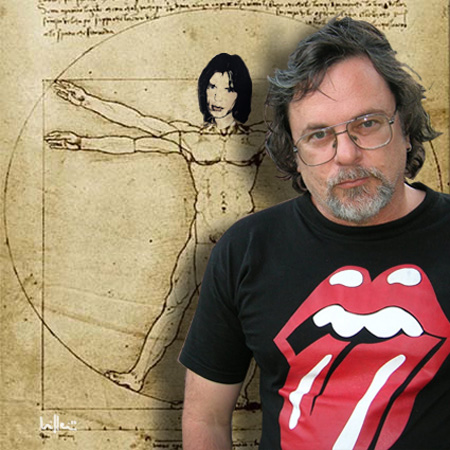

The director wanted to recreate a piece of the Renaissance which enriched the genius born in Vinci, seasoning his story with some Rolling Stones musical culture (to conform with the mannerisms of the bisexual Leonardo), and that, of course, is not part of the ode to the cinematographic guajirismo that clearly sets the tone at the festival in Havana.

I can’t stop thinking about what would have been the fate of Luis Buñuel trying to cast his surrealist pieces in the competitive Latin American cinema in Cuba; I can’t stop thinking about the anonymity that Borges would have suffered were he from Havana, for not addressing “the Latin American reality” in his stories; he would never have been promoted at the International Book Fair of Havana.

And I can’t stop thinking, even in the endless production of officials, censors, enlightened bureaucrats, selection committees, sponsors of intellectual guajirismo in the entrenched national culture, which exhibits an Island where Severo Sarduy is less known than Miguel Barnet, Tomás Sánchez less than Kcho, and where political and thematic meters are still used to define what belongs to the art of Latin America and what does not.

I hope that this rare Cuban audiovisual bird that is Eduardo del Llano has learned his lesson: meanwhile an intellectual peasant hold the reins of the cultural politics of his country, which is consistent with the exuberant underground spread his work has had inside and outside the Island, which does not try to “thin” the atmosphere of the folkloric Festival.

(Published originally in Spanish in Marti Noticias)

November 16 2011