My mother was just a girl of five living in a tenement in central Havana and I was barely one egg of the many dozing in her womb. Amid the daily grind and the first signs of shortages — already noticeable in Cuban society — not even my grandmother realized how close we were to the holocaust that October of 1962.

The family could feel the tension, the triumphalism and the collective nervousness of something delicate happening, but never imagined the gravity of the situation. Those who lived through that cruel month all behaved the same, whether they were unaware or accomplices, uninformed or ready to bring sacrifices, enthused or neutral.

The so-called Missile Crisis, known in Cuba as The October Crisis, touched several generations of Cubans in different ways. If some recall the terror of the moment, it left others of us with the constant tension of the trenches. The gas mask, the shock of the alarm that might sound in the night, the island sinking into the sea, offered metaphors for speeches and songs. Nothing returned to normal after that October. Those who didn’t live through it first hand still inherited its sense of unease, the fragility of standing right on the edge that could end in the abyss.

The days are long gone when what is said or what happens in Havana can disrupt world peace. Now we are marking the 50th anniversary of those events; studies are conducted of the declassified documents, the surviving players are interviewed and come to new conclusions.

But as happens with many songs that are all the rage one day, or with the speeches of many leaders, the passing of time makes us see these events with less passion but with a greater degree of uncertainty and confusion. Particularly when those who are looking back do so from the distance usually assumed by people who did not suffer the consequences.

Perhaps what most draws our attention now is the enormous capacity to make decisions that was taken by some individuals on matters of such great importance. In 1962 the Cuban leader was Fidel Castro, although the position of president was nominally held by Osvaldo Dorticos. If, in a moment of weakness, the Soviets had given into the temptation to leave the red button near the finger of the Maximum Leader in olive-green, as he would have liked, probably no one would be reading this article. What’s more, this article would not even exist.

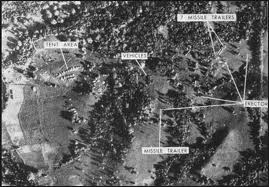

Luckily, to arm a missile with a nuclear charge and to launch it is a lot more complex than some doomsday movies would have us believe. And it was especially so in 1962, when the electronic controls required huge labyrinthine metal cabinets arranged in hermetically sealed rooms. Nor were the Soviets willing to provide the technology, while the Cubans lacked the ability to implement it. That saved us. Their own laws prohibited the Soviet Union from selling or giving such weapons to any other country in the socialist camp.

Today the danger of clandestine distribution of nuclear devices is much greater than it was half a century ago, and the fear that certain military technologies will fall into the unscrupulous hands of international terrorists in not unfounded. The surveillance capacity from satellites is also much greater. In most nations with atomic potential the ability of leaders to make a personal decisions has been lessened, and there is an awareness on a planetary scale of the unacceptability of a nuclear conflict.

The dispute about the Iranian nuclear program, and the tensions unleashed against the possible use of these weapons by North Korea or Israel, do not seem to share the imminence with which intercontinental missiles appeared ready to cross the skies in that autumn of fifty years ago.

The slogans that were shouted in Cuban plazas in those days would be frowned upon today, by the common sense that is beginning to take hold in the early days of the twenty-first century. It would sound too irrational, absurdly excessive, contrary to life. Because when European mothers put their children to bed with the fear that the sun wouldn’t rise, on Havana’s Malecon people were chanting the strident “If you come you stay”; and while the entire world was calculating with pessimistic exactitude what would be lost and what would be left standing, on this Island they repeated to the point of exhaustion that we were ready to disappear “before agreeing to be the slaves of anyone.” When the USSR decided to remove the missiles, irresponsible people in the streets hummed, “Nikita, faggot, what you give you can’t take back.”

Recently Fidel Castro himself returned to some of that puerile — almost childish — arrogance when he stated that, “We will never apologize to anyone for what we did.” His words were an attempt to surround with glory the intransigent attitude of the Cuban government during those days that shook the world.

Now, at least, we enjoy the relief of knowing that this stubborn old man of 86 is ever further from that red button that would have unleashed disaster. Every day the impossibility of his influencing the global road map becomes greater.

In the era of globalization, the authorities in Havana insist on political insularity, although the vocation of the new generations is to spread themselves everywhere. In the light of half a century we perceive that those slogans were metaphors that threatened to sweep away our reality. The political delirium that we suffered then would not survive today before the sanity and pragmatism imposed by daily survival. Obviously we have matured. The missile crisis will not be repeated on the Island, no matter how many Octobers lie ahead of us.